Ming Smith, Two Pool Players, Pittsburgh, 1991, from the series August Moon for August Wilson

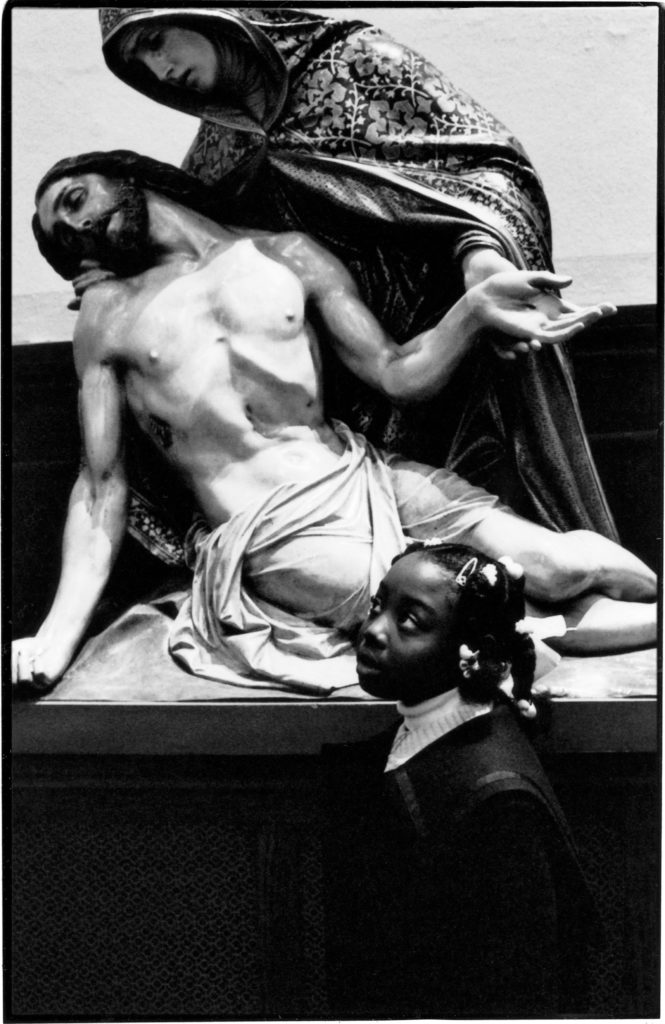

The sacredness of ordinary Black life. The heirs to the legacy of the Great Migration in the United States. The tentatively maintained enclaves in Northern cities, where people fought for safety and security. These are the recurring narratives found throughout Ming Smith’s work, in particular her photographs honoring the playwright August Wilson. Taken as she familiarized herself with the Hill District in Pittsburgh—Wilson’s home ground—Smith’s August Moon for August Wilson series (1991) is a living conversation with the characters in Wilson’s “Century Cycle” plays (1982–2005), in which he immortalized and elevated ordinary Black people’s lives. Smith’s images document the fortitude and fragility of community, built against encroaching Jim Crow laws, the Klan, and later, the limitations created by redlining, institutional discriminatory practices, and everyday racism.

Smith, who grew up in a literary family, had an immediate affinity for the subtle metaphors woven throughout Wilson’s plays. Two Trains Running (1990), for instance, is a metaphor for the dual railway tracks we ride along, simultaneously and often obliviously: one track transporting us through life, and the other hurtling us towards death. She also understood Wilson’s characters intimately. The profound disappointments of their lives and the fortitude with which they faced those hardships were similar to her own experiences, and the stories of those with whom she had grown up.

In Two Trains Running, which is set during the Civil Rights Era, Wilson’s characters glimpse their political potential. Yet economic forces beyond their control and local government policies, euphemistically called “urban renewal programs,” are forcing them out of the neighborhoods they built, and with that, the hard-won power and protection they created through community. Memphis Lee, a self-made local businessman, looks around at shuttered shopfronts and laments: “Supermarket gone. Two drugstores. The five and ten. Doctor done moved out. Dentist done moved out. Shoe store gone. Ain’t nothing gonna be left but these niggers killing one another. That don’t never go out of style.”

Another character, Hambone, is infamous in the neighborhood for demanding a ham from Lutz, the proprietor of a meat market. Hambone believes that he was promised this ham as payment for painting Lutz’s fence, but the promise—and the fair wage for fair work that he expected—was never fulfilled. Each time he shouts, “I want my ham!” from across the street, Lutz offers him a chicken instead. This might seem like a comical scenario, emphasized by other characters who don’t fully comprehend why Hambone remains so insistent; but the futility of his request—for justice, for a promise to be kept, for his work to be recognized for its worth—mutes the humor with tragedy.

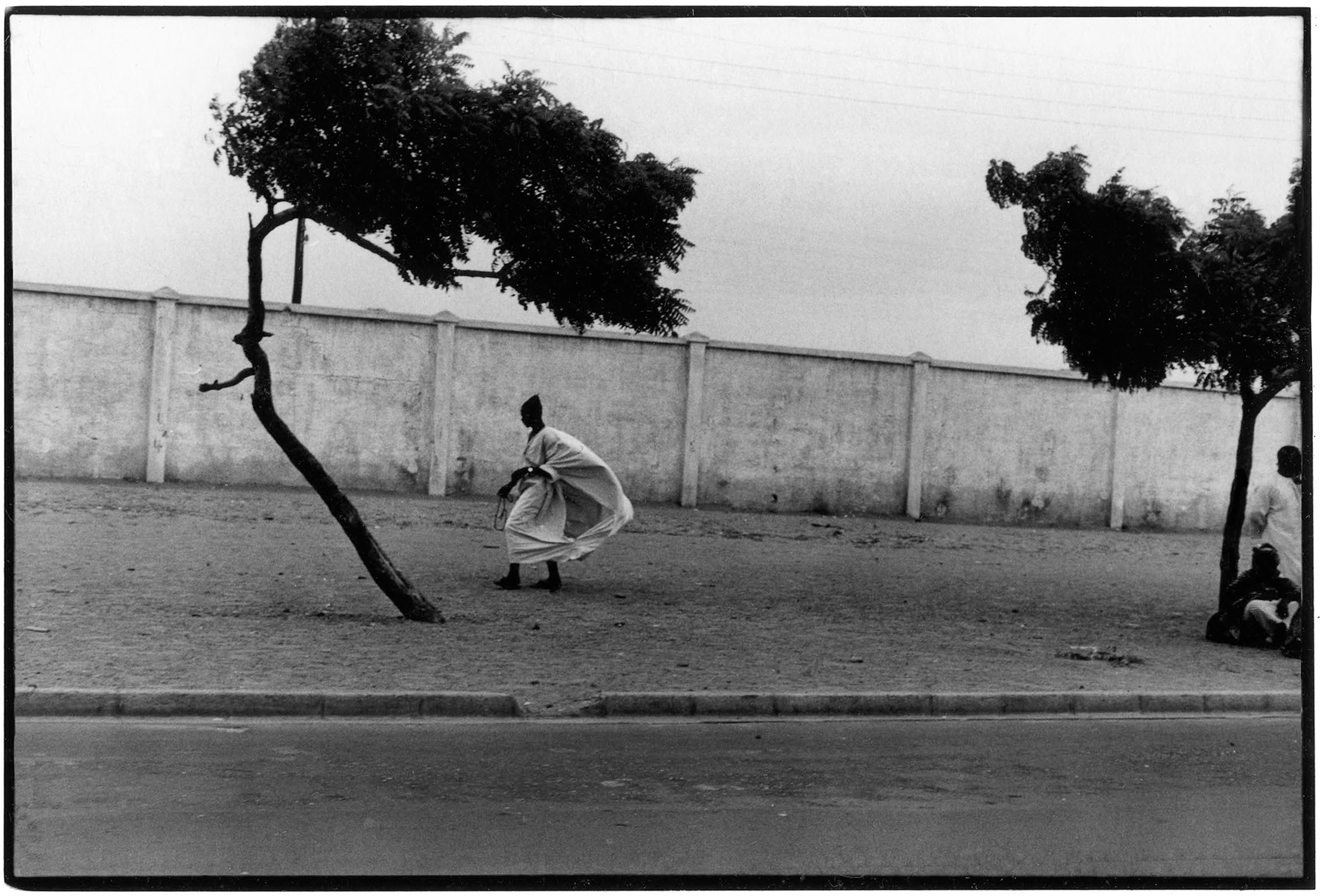

For Smith, Wilson’s characters and the dilemmas they faced were living metaphors that served as references for the all-too-real struggles of Black folk she knew. As a photographer, she wanted to find a visual language that reflected these same complexities. Smith’s style of shooting—which results, as noted in the press statement for her 2017 exhibition at Steven Kasher Gallery, in New York, in blurry, “out-of-focus images in which the finer details of figure and background are obscured”—allowed her to be less focused on making documentary work “than creating a personal response to that life.” Her deliberate use of a slow shutter speed and low light conditions for photographing the August Wilson series suggests the aliveness and liveliness—antidotes to unpredictable conditions—of those she photographed. Her photographs speak to the fleeting nature of her subjects’ victories, the invisibility of their striving, and the complexities of the struggles she knew to be the undertow of each life.

Smith was raised in a Columbus, Ohio, household hearing her grandparents recite poetry. They gave equal attention to many poets—Black and white—but loved Paul Laurence Dunbar in particular, relishing the Black vernacular and the humor in his poems. There was an alchemy created by reciting a poem in one’s kitchen. The ordinary became heroic.

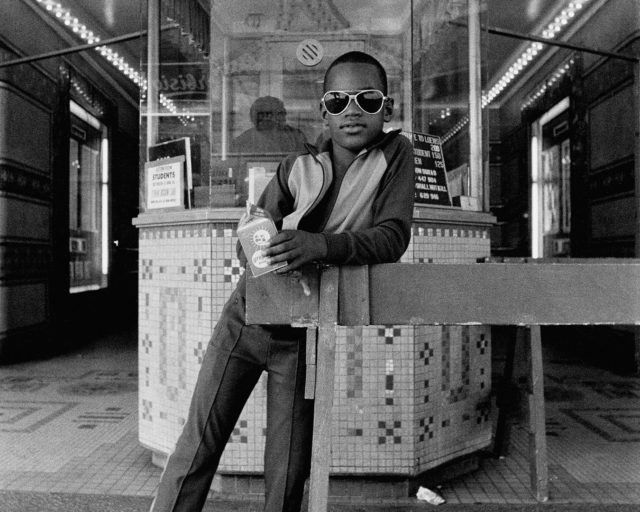

Her family’s fondness for African American folklore inculcated a similar, inquiring love in Smith. Her father, a pharmacist, let Smith come over to the drugstore after school and operate the soda fountain and serve ice cream to customers—a big responsibility that she enjoyed. Once, he called her there to see a young boy, Pierre (who was about her age), perform hambone on the pavement outside the store—slapping his arms, thighs, and face, stomping his feet in rhythm, and turning on a dime. She also remembers an older gentleman, Mr. Charlie, who worked as a mason. “If you looked at him without knowing who he was or what he did, all you might see was a shabbily dressed man who had a pint of liquor in his back pocket,” Smith remembers. Mr. Charlie took pride in his exquisite craftsmanship, sometimes adding color into the cement, and ensuring that his work was neat and polished. One of the important lessons Smith learned by observing Mr. Charlie was that if one respected the materials with which one worked, and did the work with care, one could live life with dignity. No matter how others may have seen him, he was a loved and highly respected elder in the community.

Although her neighbors may have been unremarkable in the larger world beyond the East Side, in her grandparents’ and parents’ eyes, they were worthy of attention and respect; their ordinary lives and deeds were worthy of being narrativized, immortalized into stories that lived on in the community. If work was done with integrity, it brought honor: “Even as my grandmother hung the washing, she hung it just so. There was a right way to do it.”

According to a 2018 article by Joel Oliphint in the local newspaper Columbus Alive, the East Side in Columbus was a vibrant community that grew exponentially during the Great Migration and after World War I, with African Americans making up about ten percent of Franklin County by 1930. The East Side neighborhood was “an all-class community, and it was conceptualized, designed and built by the community,” said East Side native Julialynne Walker, who coauthored a 2014 report on African American settlements for the Columbus Landmarks Foundation. It had many Black-owned businesses—“retail shops, theaters, restaurants, nightclubs, medical offices, banks—and even its own unofficial mayor,” writes Oliphint; it also had rooming houses for Black musicians, who came to perform at clubs downtown but who could not stay in hotels downtown since they only allowed white patrons.

Smith caught glimpses of the country changing when she went to Detroit to visit relatives, where they could sit where they wanted to in movie theaters. Her departure from Ohio was fueled by the desire to get away from Jim Crow laws that still legislated her life as a Black person, and the need to leave painful personal experiences of racism behind. She wanted to leave her anger and frustration behind too.

After graduating from Howard University, Smith moved to New York City. There, she discovered a different world among the community of artists, writers, playwrights, photographers, dancers, choreographers, and models. As a model herself, she loved meeting other women at auditions. “All of us trying to move up from places we didn’t like, trying to survive,” she recalls. “I’d meet all the designers, the makeup people and the hairstylists, all of us in this creative group. My friend who was an artist chose and arranged the clothes. The makeup person was a dancer. We were all doing several things.” She began to take her camera on set. She took photos of the models, costume designers, makeup artists, singers, and actors alike—backstage, relaxing. At other times, she turned the lens on herself, documenting her own face, as part of her visual diary.

By the 1990s, Smith, who had been largely invisible to the white art establishment throughout most of her career, was looking to do more with her photography. An avid reader, she was drawn to August Wilson’s plays, especially the ten plays that comprise the “Pittsburgh Cycle” (or “Century Cycle”), each of which explores the complexities of individual African Americans and their experiences, one play for each decade within a hundred-year span. Wilson’s works focus on lives that would ordinarily go undocumented and unremarked, modeled on those he knew from the Hill District of Pittsburgh, where he grew up. Smith found that Wilson’s plays were a conduit to a past she had left behind—it was like stepping back into her childhood in Columbus, listening to Mr. Charlie’s yarns, where young Pierre performed hambone outside her father’s drugstore. Wilson’s writing gave her a magical return, without the pain associated with the racism of her childhood and youth. Smith felt an immediate affinity for Wilson’s plays and the characters he conjured to life. She identified with their pain, but also with their ironic humor and the way love buttressed their struggles.

As Smith tells Janet Hill Talbert in an interview for Smith’s Aperture monograph, “After I saw August Wilson’s play Two Trains Running, I wanted to go to Pittsburgh and shoot.” With nothing but a phone number for August Wilson’s sister Freda, she bought a Greyhound bus ticket to Pittsburgh. From there, she tracked down Wilson’s haunts in the Hill District, where he had based most of his “Century Cycle” plays, and visited some of the places he referenced. She could immediately picture Wilson’s characters, recognizing their similarities to people she knew from her own childhood. In Pittsburgh, she tells Talbert, “the people were light to me. They were light within all the violence and all of the pain. They were folkloric.”

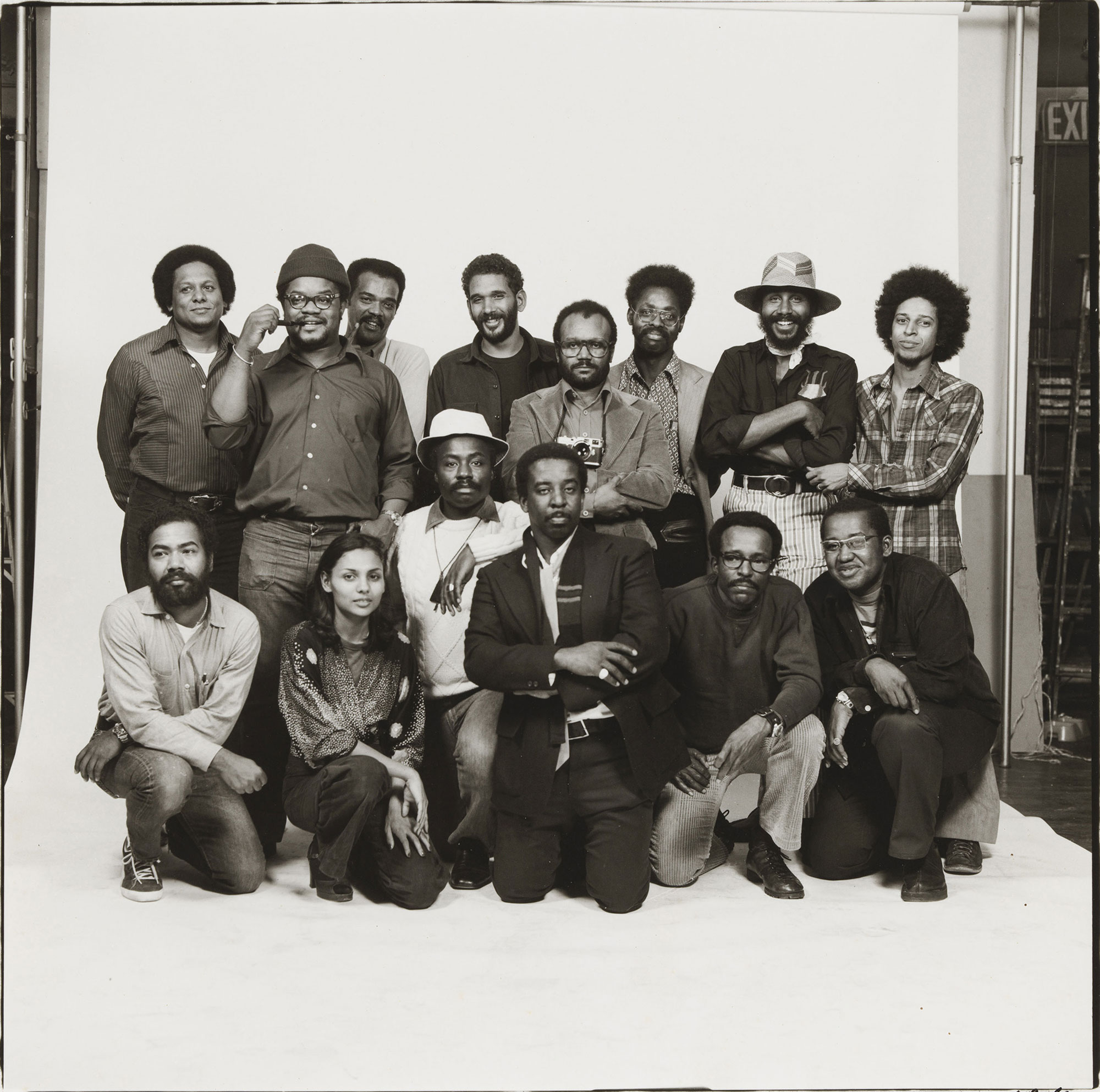

She became more familiar with the Hill District, documenting what she saw unfolding in real life. Like Wilson’s writing, her photography remarked on the quotidian, riffing between history and the present, between fiction, playacting, and reality. Initially, her goal, as she continued to photograph what came to be known as the August Wilson series, was to launch collaborative work with Wilson. She hoped to produce a book like The Sweet Flypaper of Life (1955), conceived by the first director of Kamoinge, Roy DeCarava, and the poet Langston Hughes. Smith owned a copy, signed by DeCarava, and took it with her when she met Wilson at a talk he gave. She remembers that he was genuinely interested in her proposal to do a collaboration—Wilson’s “eyes opened wide!”—and he asked to borrow her book. Though their joint project did not come to fruition (and Wilson never returned the book), her interest, as the first woman admitted into Kamoinge, remained aligned to the meaning of the Kikuyu word—she continued to be interested in “acting and working together”—creating conversations with writers, performers, and other artists.

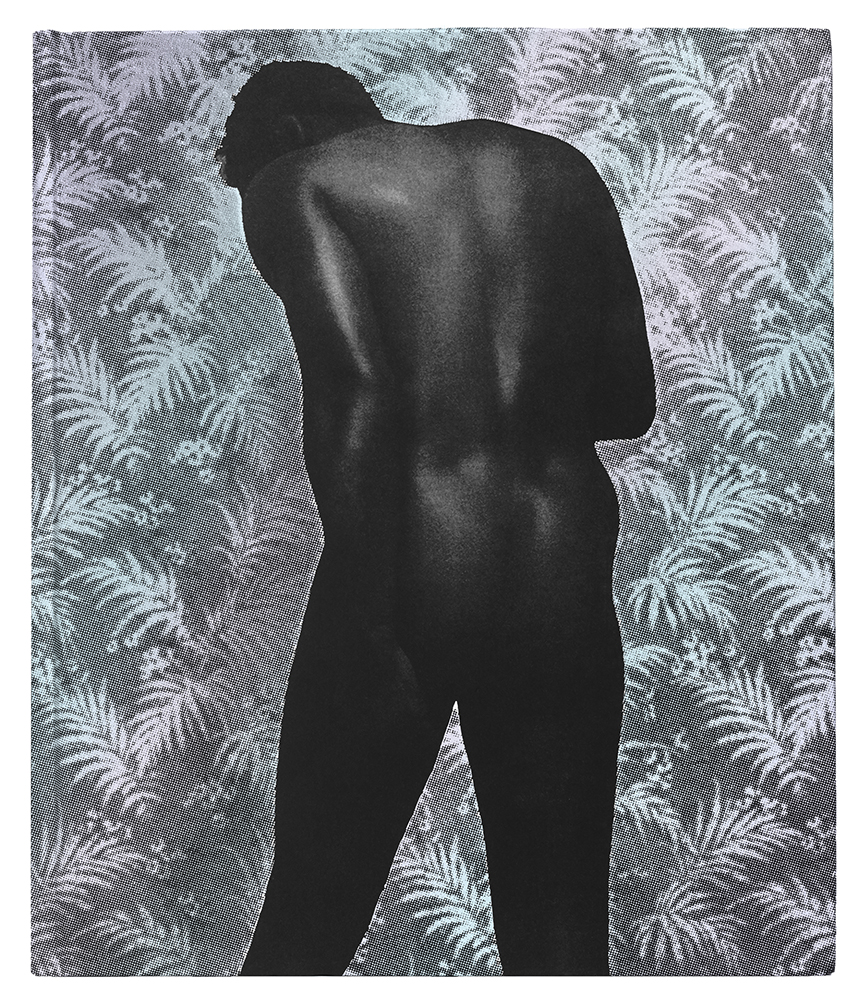

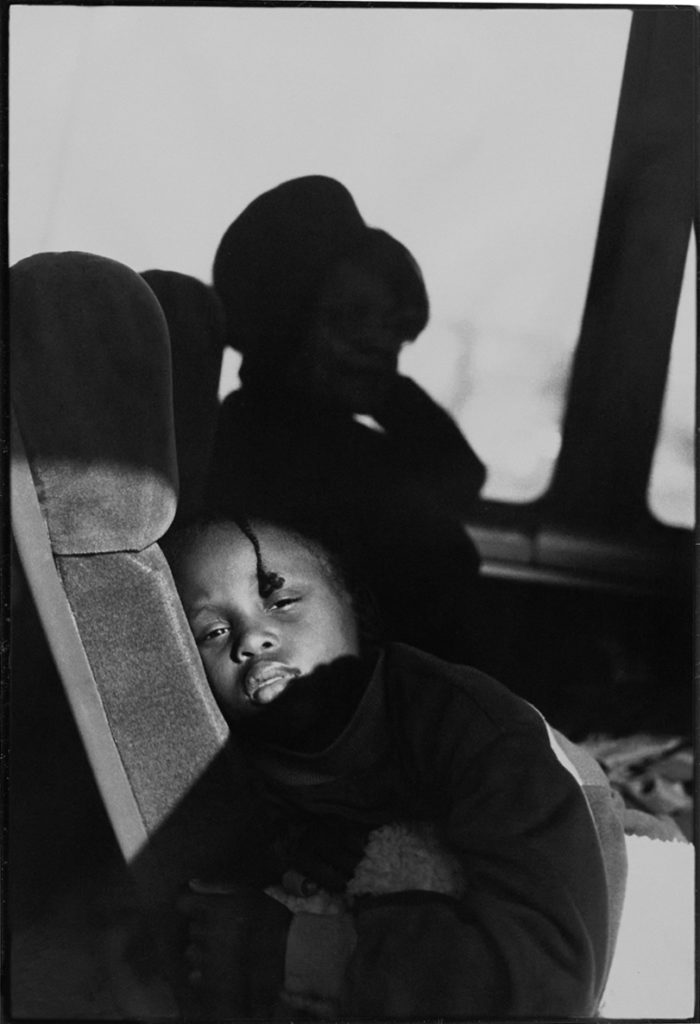

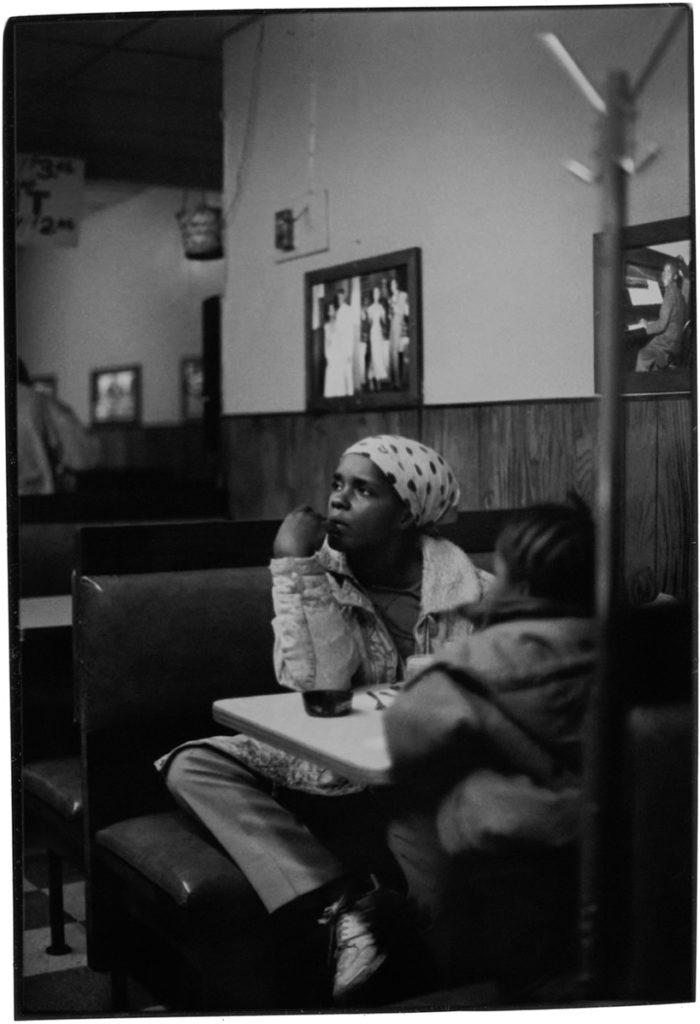

Wilson’s plays involve ensembles of actors, emphasizing the role of community for Black people’s survival, and for creating joy in each other’s company. Smith’s Two Gentlemen in Hats Eating Lunch at a Senior Center (1991) and Two Pool Players (1991) are testaments to those ordinary ways of creating threads of sustenance. There’s Aunt Ester (1991), in her old fur, brooches, and crazy knitted hats—giving us a good look from under the brim as she passes by. They may be down and out, but they are getting by, with help from each other. But among the dilapidated storefronts with peeling advertisements from a bygone era, diners, and poolhalls, Smith’s photographs from this series speak about loneliness. As John Lahr notes in a 2001 profile of Wilson for the New Yorker, Wilson’s plays are populated by those who “have a song that they can’t broadcast [or] have given up singing; some have been brutalized into near-muteness; and others have turned the absence of a destiny into tall talk—the rhetoric of deferred dreams.” Smith’s characters likewise embody those would-be songs, those unrealized dreams.

In Mother and Child Deciding (1991), a young woman is seated at a diner booth with a child, both bundled in winter jackets. Her body is turned to the right, with her leg hoisted onto the booth’s seat, revealing a worn sneaker; her right elbow is placed on the booth’s table, and her little finger touches her lower lip. Her turned face and her outward gaze into the middle distance indicate that she is contemplating the menu posted on a board, or the photographs hung on the wall above the wood paneling. But her wistful face tells us that her thoughts are occupied by worries that have accompanied her here—worries that she cannot share with the child. Love Barber Shop Jazz (1993) shows the dark interior of a barber shop, famously the center of community in many Black neighborhoods, long after the customers—and their gossip, slander, loving stories, troubles, and cadences—have filtered out through the doors. The barber is bent, all his love focused on the trombone in his hands. The instrument, the notes it produces, is his final conversation—a communion that allows him to unload the exhaustion of the day.

All photographs courtesy the artist

If Smith, like Wilson, set out to represent ordinary, otherwise unremarkable Black life and Black experiences, her self portraits, too, might be a continuation of that impulse. As a former model, Smith was used to being in front of the camera—but with the expectation that she play a character, exude desirability, and often sell something else as a desirable object. In focusing the camera on herself, she renegotiates the terms and conditions of that objectification, creating portraits that reflect versions of herself as she wishes to be seen. This, as we know, is a luxury for most Black people, especially in the decades in which Smith began her photography. (It is still a luxury in this century, as we continue to see the use of the camera to document Black people at their most abject, and often without their consent.) When Smith picks up her camera and photographs the intimacy of her face and body in a multitude of situations and places, it is a response to her own beautiful aliveness, her situatedness within a moving world, and the movement in her own emotional and psychological self.

Smith’s photographs of Wilson’s neighbors in the Hill District are similar readings of fleeting moments, portals into the past. Through engaging deeply with Wilson’s plays, his characters, and their real-life counterparts, she traveled into her own history and, through memory and imagination, relocated herself within her own childhood. The resulting photographs are shout-outs that acknowledge people she remembers, recognizes, and honors—beloved characters who continue to live in her present. And she is among them, as one of their own.

This essay was originally published in Ming Smith: An Aperture Monograph (Aperture/Documentary Arts, 2020) under the title “A Song They Can’t Broadcast.”