Cruising and Transcendence in the Photographs of Minor White

Writer and curator Kevin Moore on Aperture founding editor Minor White’s convoluted relationship with photography and sexuality. This essay is an online-only feature accompanying Aperture magazine’s Spring 2015 issue, “Queer”.

Minor White, Tom Murphy, San Francisco, 1948, No. 9 from the series The Temptation of St. Anthony Is Mirrors, sequenced 1948 © Trustees of Princeton University, and courtesy the Minor White Archive, Princeton University Art Museum

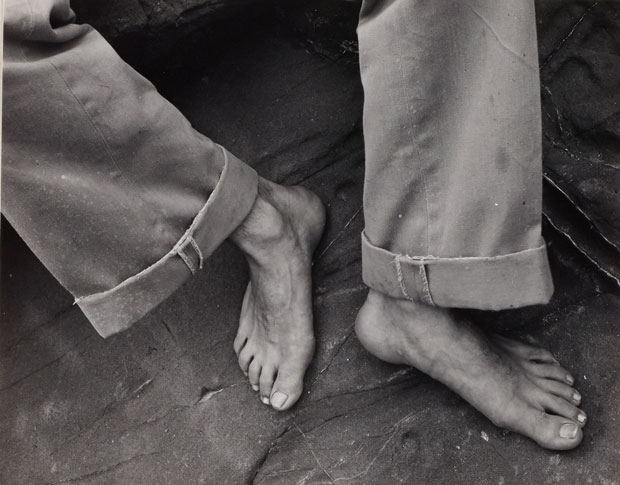

Minor White, Tom Murphy, San Francisco, 1948, No. 8 from the series The Temptation of St. Anthony Is Mirrors, sequenced 1948 © Trustees of Princeton University, and courtesy the Minor White Archive, Princeton University Art Museum

“A banquet of frustration”: Minor White penned the phrase in 1939, after reading T. S. Eliot’s 1922 poem The Waste Land. “I perceived that if one could put out the energy to produce a banquet of frustration, then frustration had power,” White commented.“It was worth pursuing.”(1) White had arrived in Portland, Oregon, two years earlier, having completed a degree in English literature at the University of Minnesota, where he had had “a taste of poetry.”(2) Portland is where White’s determination to “put out energy” for ideas took the form of what would become a lifelong obsession with photography. The medium would bring continuity to a life of soul-searching and spiritual promiscuity.

The “frustration” to which White refers need not be reduced to his homosexuality, which had troubled him since his teen years. White consistently sought to universalize his suffering, drawing on literature, psychoanalysis, and myriad spiritual texts to cope with his particular perspective on the human condition.(3) But his sexuality remained a thorn in his side. Moreover, it was something he felt compelled to express, despite fears of persecution and rejection. In one of the artist’s most commonly repeated injunctions, to “look at things to see what else they are,” White hit upon a metaphor for both evading and revealing his personal circumstances.(4) White’s “banquet of frustration” was thus both an ongoing torment of forbidden desire—with stolen moments of ecstasy, both physical and emotional, by all accounts—as well as an expression of mundane struggle informed by Eliot’s sweeping characterization of the modern world.

In addition to navigating the postwar period’s harsh treatment of homosexuals, White found himself in an artistic predicament that was related to his sexuality. Embracing the role of an inheritor of the American modernist photography tradition—defined by such titans as Alfred Stieglitz and Edward Weston as a “straight photography” ideal—White found that his instincts ran aground. To emulate Stieglitz and Weston was to adopt not only an aesthetic of sharp focus and monumental form but a sensibility of optical candor and forthrightness. In the work of White’s mentors, this attitude often played across the contours of the female form (or objects resembling the female form), asserting with force man’s desire for woman, and establishing that desire as a locus of modernist creativity.(5) Thus from the start White was driven down a path of artistic evasion.

In that sense, White’s banquet was something more: it proposed a way through his predicament via an acceptance of frustration but also, in a tremendous lurch of positive thinking, transformed that frustration into an engine of creativity. If for Stieglitz and Weston heterosexual desire lay close to the mysterious centers of creativity, for White it was the frustration caused by his own “aberrance” that ascended to metaphor. Sexual desire became frustrated sexual desire and, for all White’s efforts at emulation, his photography could not sustain the optical machismo of his forebears; it could not continue in the prescribed modernist tradition. Indeed, despite his own best efforts, White’s “perversion” converted that tradition into something else, retuning the self-assurance of American modernism to a register of ambivalence and ambiguity, countered by proclamations of spiritual bravado.

The duplicity one senses in White’s career, in both his writing and his images, stems certainly from this frustration about sexuality (as Peter Bunnell has written,“White’s sexuality underlies the whole of the autobiographical statement contained in his work”),(6) but it also mirrors a much larger countertradition found within modernism itself, a romantic tradition that draws from Romanticism, Symbolism, Dada, and Surrealism. More specifically, White’s frustration coincides with the collapse of modernist ideals during the postwar era. This passage in the history of photography, if examined at all, is normally pinned to the arid vision of Robert Frank.(7) Aesthetically, White’s vision was less dark than Frank’s, and in no sense nihilistic. Yet White’s work embodies a critical shift in consciousness, from the heroic modernist notion of “truth in appearances” toward the acknowledgment—and even the cultivation—of illusion, deception, and buried meanings. White’s banquet of frustration would look like a tea setting compared to the theoretical abattoirs of generations of later artists; nevertheless, the historical narrative of photographic modernism’s dissolution owes an early chapter to White and his longing for transcendence, which he seems not to have attained.

In 1939 White was living at the Portland YMCA, where he had organized a camera club and had built a darkroom and modest gallery for exhibiting pictures. White’s photographs from this period concentrate on the environs of Portland, particularly the area of the commercial waterfront, which was undergoing demolition for redevelopment. Hired by the Oregon Art Project, an arm of the Works Progress Administration (WPA), White trawled the city’s Front Avenue neighborhood, documenting the nineteenth-century buildings with cast-iron façades that were about to be torn down.(8) White’s photographs are anything but clinical. His street views, many taken at night, have a ghostlike quality, with the occasional lone figure haunting the wet pavement; boarded-up doorways are cast in deep shadow; and mercantile objects, heaped onto the sidewalk before emptied warehouses, take on a forlorn anthropological character.(9)

Among these pictures is a group of five depicting a handsome young man leaning in a doorway on Front Avenue. He is dressed like a laborer in jeans, work shirt, and boots, but there is something of the dandy in the raffish positioning of the man’s newsie cap, the tight cut of his trousers, pulled high and cinched at the waist, and the studied nonchalance of his pose. In one image, his hand is shoved into a pocket, leaving the index finger exposed and pointing downward toward a prominent bulge. Most importantly, he gazes—not at the photographer but down the street— intently and expectantly, as if anticipating something that has not yet come into view. A second photograph shows the man from behind, revealing the nape of his neck, a pair of rounded buttocks, and white stains splashed down the right thigh of his trousers. The pose suggests that he is urinating in this abject doorway with its peeling paint and debris underfoot; he could be taken for a plasterer relieving himself during a break. Another image, taken in a different boarded-up doorway, shows the man leaning with one arm raised and smiling coyly (again, not at the photographer), with his thumbs slipped under his belt and his fingers cupped, calling attention once again to his bulge. An “Air Circus” poster behind him advertises “Tex Rankin and other famous flyers” as well as “stunts” and “thrills.”

The scene is both explicit and coded, even to contemporary eyes. This handsome loitering man might have been taken by certain passersby for an ordinary laborer, on break or looking for work. Others might have recognized him as a man looking for sex (or for another kind of work) with other men. White’s sexual interest in men and his approach to looking at things “for what else they are” stratify the two narratives, establishing layers of meaning on parallel planes. This man is both a laborer and a cruising homosexual. He is, then, just what the photographic image in general would come to signify for White: a common trace from the visible world, transformed into another set of charged meanings.(10)

Throughout his life, White was an intellectual grafter, transposing, with various degrees of success, methods and ideas from art history, literature, religion, psychology, and other photographers to his own work. For example, he named his diary “Memorable Fancies,” after a phrase in William Blake’s Marriage of Heaven and Hell (1790–93) and, sometime later, structured his essay “Fundamentals of Style in Photography” after Heinrich Wöfflin’s classic study Principles of Art History (1915).(11) By 1939,White had read not only Eliot but also Walt Whitman, whose life and work had long served as a beacon to homosexual men in search of validation and social cohesion across geography and time. Whitman’s 1855 epic Leaves of Grass, a highly democratic and modern exaltation of the body and the material world, became White’s inspiration for another urban documentary project, this one begun in San Francisco in 1949, titled City of Surf. In that series, comprising six thousand negatives—ostensibly a catalogue of everything in the city, from Chinatown to the financial district to new suburban housing—White maintained a democratic eye. Architecture is shot head-on and in full sun; people (including women) appear on the street, going about their business in routine fashion; children play on the sidewalks. Indeed, the photographs in this series are the most uncharacteristic in White’s entire œuvre, conveying a detachment and spontaneity associated with documentary photography in its purest form.(12)

White’s earlier Portland series, by contrast, is the darker product of a romantic turn of mind and conveys not the affirmative, civic-minded Whitman of poems such as “A Broadway Pageant” but the melancholy, searching Whitman of the “Calamus” poems.(13) In Portland, we see White engaging Front Avenue for its sense of mystery and possibility, an investigation among darkened doorways and in the silhouettes of passing strangers for moments of revelation. More than simply a celebration of the manifold aspects of the city, the desired charge might be specified as the possibility of an erotic connection, however ephemeral, as proposed by Whitman in “City of Orgies”:

City of orgies, walks and joys,

City whom that I have lived and sung in your midst will one

day make you illustrious,

Not the pageants of you, not your shifting tableaus, your

spectacles, repay me,

Not the interminable rows of your houses, nor the ships

at the wharves,

Nor the processions in the streets, nor the bright windows

with goods in them,

Nor to converse with learn’d persons, or bear my share in

the soiree or feast;

Not those, but as I pass O Manhattan, your frequent and

swift flash of eyes offering me love,

Offering response to my own—these repay me,

Lovers, continual lovers, only repay me.(14)

In his 2003 book Backward Glances, Mark Turner compares the cruising homosexual, as conjured in Whitman’s poem, to the flâneur, a common figure in the literature on modernism, established in the writings of Charles Baudelaire. (White owned a copy of Baudelaire’s Flowers of Evil [1857] and a print of Nadar’s portrait of the French poet [ca. 1854], which is now in Princeton’s Minor White Archive) For Baudelaire, walking in the modern city was a fragmentary and ephemeral experience that allowed the poet to conjure what Turner calls “a dreamworld of the imagination.”(15) Like the cruiser, the flâneur’s activity was fundamentally visual, and Baudelaire talks, too, about making a form of contact through the eyes of passing strangers.(16) But for Baudelaire, the glance is not reciprocated. He looks for information that will activate the mind. In that sense, the flâneur’s activity is one of observation; he searches, but for something unspecified, unanticipated, and he keeps a certain distance. In Robert Herbert’s phrase, he is an “ambulatory naturalist,” “sizing up persons and events with a clinical detachment as though natural events could tell him their own stories, without his interference.”(17)

The cruising homosexual, by contrast, seeks connection, exploiting the ambiguities of the modern city by reading the visible signs for other levels of meaning. In an important sense, he passes for the flâneur, participating as a kind of player on the stage of the urban theater—a loafing, loitering man, looking around—yet he, like others capable of reading his intent, acknowledges sex as the motivating force under-lying his actions, regardless of whether sex is part of the outcome. (As Turner notes, “Sex may be the point of cruising for some, but sex and cruising are separate interactions.”)(18) Aware of the sexual basis for his actions, reading the modern city on various levels at once, the cruising homosexual presents an evolved modern persona, one engaged in the simultaneous adoption and blurring of social categories. He is two very different things at once: the detached, respectable flâneur and, just below the surface, the engaged, suspect cruiser. Behaviors embedded within behaviors, meanings layered upon meanings, visible to all yet decipherable to only a few—one might be describing the disruption of straight photography more generally. Presented with such a system of oblique actions, promises of revelation, and the possibility of social recognition and engagement, White was naturally enthralled.

Depending on the circumstances, Whitman could assume dual roles. He plays the flâneur in poems such as “A Broadway Pageant,” observing and recording all the sights of the city with an observer’s eye; and he plays the cruiser in poems such as “City of Orgies,” walking with a more overt and specific purpose. White similarly plays two parts. In City of Surf, he creates a cumulative portrait of San Francisco based on random, chanced-upon observations, whereas in the Portland series his purpose is much more personal, searching, and erotically charged.

This ability to oscillate between two roles, sometimes playing both at once, might be seen as fundamental to White’s approach, distinguishing him from other photographers working within the modernist idiom during this period. Particularly as a disciple of the American modernist tradition, White might be credited with having “queered” documentary photography. His pronounced and duplicitous alteration of the “straight-photography” tradition—framed here as flânerie lapsing into cruising—is emblematic of the larger fate of modernist photography to a degree that White himself may not have intended or recognized.(19) White’s images stage the breakdown of a heroic modernist tradition that pursued photographic “truth” in the form of a clear image: the “straight photograph.” His work leads us inexorably to an understanding of the photograph as embodying an array of meanings, some evident and put there purposefully by the artist, some only tentatively suggested or actively veiled, and many not intended by the artist at all but projected by the viewer. In other words, White, who subscribed officially to the orthodoxies of straight photography yet consistently challenged and undermined that philosophy’s claims of veracity, helped bring modernist photography to the doorstep of post-Structuralism.(20) White was a hero flirting with tragedy.

Aesthetically, White’s Front Avenue photographs bear much resemblance to those of Brassaï, whose night pictures of Paris, many of them published as Paris de nuit in 1933, depict abandoned streets and mirrored interiors, suggesting danger and sex as portals to another reality. Brassaï’s photographs, which explicitly featured prostitutes and homo-sexuals, were swiftly appropriated by the related rhetorics of Surrealism and “Old Paris,” the former proposing violence against bourgeois proprieties, the latter nostalgically depicting Paris as a place of social decadence. In both these contexts, night views of the city and the furtive activities occurring there under cover of dark conveyed a sense of the social subconscious, revealing—after Freud—the animalistic impulses lying just below the surface of daylight respectability. Although some considered their content shocking, Brassaï’s photographs function on a primary level as straightforward documents of nightlife in Paris.(21) His photograph of a potential john eyeing a prostitute in a doorway, a print of which White owned (probably acquired in the 1960s; now in the Minor White Archive), tenders a clear glimpse of an illicit exchange. The narrative is so self-explanatory that speculation is unnecessary.

For comparison, White’s 1939 photograph of a Portland bridge shows a night view, animated by the streaking headlights of cars and a trolley. Though mood predominates, a vague narrative is suggested by a light appearing in the window of a lonely tower at right and a man (or group of men) in a doorway at left. The atmosphere is certainly reminiscent of Brassaï but the narrative intent is less clearly stated. In an important sense, White’s picture is closer in spirit to Brassaï’s less anecdotal photographs, such as the purely atmospheric, unpeopled images from Paris de nuit and his photographs reproduced in various Surrealist publications. Brassaï’s ca. 1932–33 photograph of the Tour Saint-Jacques, for example, which appeared in André Breton’s 1937 novel L’Amour fou, presents a deadpan view of the tower against a dark sky. Understood within the context of the book’s narrative, the photograph suggests the site of an amorous nocturnal encounter between Breton and a woman; their “crazy love” is ultimately transformative.(22)

White’s photograph, conveying the same mood of hopeless longing, hinges on a similar note of banality and ambiguity, darkened and enlivened through atmosphere and a sense of strained human relations. In the context of Mirrors, Messages, Manifestations—White’s ostensibly revealing monograph of 1969, sequenced and edited by White himself and containing numerous excerpts from his diaries—the photograph of the Portland bridge is understood to be as much a snapshot of White’s state of mind on that evening in 1939 as it is a document of Portland’s architectural history. “What we see is a mirror of ourselves,” he would later write, affirming his allegiance to Freud and a psychoanalytical approach to the comprehension of photographs.(23) For both White and the Surrealists, the night street, seemingly abandoned, was alive with promise and possibility. The photograph’s documentary character, delineating with emotionless clarity the contours of the empty street, served paradoxically to both shield and suggest a wealth of personal feeling not actually depicted in the photograph.

Behind closed doors, White took pictures with more explicit homoerotic content. In 1940, he made a series of art nudes of model Gino Cipolla in the shadowy style of contemporaneous male nudes by George Platt Lynes. White also made “beefcake” portraits, the classic fare of physique magazines, which served as thinly veiled newsstand erotica for homosexuals.(24) Both contexts encouraged de-emphasizing the male genitals. In this instance, White squared his art nudes with the standards of the female nude, treating the contoured (and hairless) body as a sculptural object, while in the beefcake portraits he made use of bodybuilders’ poses—these having been borrowed in turn from classical sculpture—often to kitsch effect.(25)

Although White would continue to photograph the male nude in private throughout his life, his most concentrated effort in this subject area occurred during his early years in Portland and San Francisco, from 1937 to 1953. Abundant and explicit, White’s male nudes from this time coincide with a period of pronounced sexual activity for the artist.(26) More importantly, the nudes proclaim his adherence to the widespread modernist belief in sex as the wellspring of creativity, which White could only obliquely acknowledge. In a 1947 letter to Ansel Adams, White postulated that “the basis of man’s art his soul, his heart, or his genitals . . . once they were all the same thing.”(27) Cipolla, in White’s rendering, might be seen to resemble a Weston pepper, desexualized in equal measure to the vegetable’s eroticization.

To both hide and reveal “the sex generator,” as he referred to his creative core, White maintained a semantic distinction between private and public imagery—between pictures that were merely “expressive” and those that were “creative.”(28) This distinction is spelled out in an often-reprinted passage from his letter to an unidentified photographer, written in 1962: “Your photographs are still mirrors of yourself. In other words your images are raw, the emotions naked. These are private images not public ones. They are ‘expressive’ meaning a direct mirror of yourself rather than ‘creative.’” White goes on to recommend Richard Boleslavsky’s 1933 book Acting: The First Six Lessons, which discusses what White called the “clothing of the naked emotions that is necessary to art.”(29) Rarely is White so lucid in his prose and so concrete in his advice. Reading the entire letter, one realizes that, in addition to offering aesthetic criticism, White was moved to protect a fellow soul struggling with homosexuality as White had struggled, and continued to struggle. The complications that White describes can only be read as his own: “These prints outline for me a rather tragic story of a man’s life. . . .The story is familiar to many people in our society: childhood home, for some reason the sex wires get crossed, confusion, self pity, anger, guilt all arise in various combinations. . . . Thereafter come the twistings caused by psychological blocks, the anger and the disintegration . . . seen as fear, self pity, vanity and a host of posturings. And there is no end to it, the inner conflict is neither resolved by solution nor by death.” White concludes with what might be considered a succinct summary of his own career path, working through shame toward creative release:“[I] further suggest with a welling heart that you try to universalize your private images and make them for the love of other people.”(30) Sadly, love of self is not acknowledged as an option.

White’s own attempts to universalize such volatile private images took many forms. As discussed,the pictures of Cipolla reference an art tradition of the nude. Yet even with the artistic lighting, sculptural pose, obscured sex organs, and averted eyes, the subject matter remains too hot to handle; not surprisingly, none of the male nudes were published in White’s lifetime.(31) In other instances, as in a clothed version of the “beefcake” model mentioned earlier, White exploits the ambiguity of pose to create an image that might be taken for an actor’s portrait. (Indeed, he was working as a photographer of actors and theater during this period; White was fascinated with actors’ ability to shift personae,“to be at once the real and the imagined, one person and another,” as Bunnell puts it.)(32) The context created by the more provocative depiction of this model, made during the same session, particularizes the picture’s meaning. Though the model’s attitude may be read as that of the classic Hollywood rebel (Marlon Brando, James Dean), the gaze also suggests cruising. And here again, the model is cruising someone else, not the photographer.

White fell in love with this averted pensive gaze, and imported it to the landscape around San Francisco, where he took up a teaching post in 1946. Moved to a natural context, the gaze starts to seem “purified,” its sexual charge grounded in a discourse of aesthetic reverie, following a Symbolist tradition of ethereal beings as rendered by Clarence H.White, George H. Seeley, and F. Holland Day.(33) White’s 1948 photograph of Rudolph Espinoza, taken in the sun-splashed doorway of an abandoned rural building, is in many respects the same picture White took on Front Avenue in Portland in 1939. Here, though, the image of the cruising homosexual is subsumed in a symbolic program White had been developing and cementing for some time: doors and windows represent thresholds to alternative states of being and the handsome gazing man is a stand-in for the artist, focused on channeling a higher form of consciousness. A photograph taken on the same day as that of Espinoza, quite possibly of the same building, shows the interior of a “bawdy house,” where the discovery of graphic homosexual graffiti renders a similar sense of revelation, though in baser form.

Despite its evident expressive power, the graffiti photograph was exactly the sort of image White felt needed to be kept private, to be altered and universalized “for the love of other people.” Through Freud and poetry, as well as his own guarded experience,White understood meaning as a layered and shifting process, yet he seems not to have grasped the full potential of such ambiguity in relation to the literal-minded medium of photography. Photographs, after all, were ostensibly documents of a given subject matter, some subjects being more acceptable for public viewing than others. If initially White thought of photography as something to draw him out of his introspection and into the world (as he had attempted in City of Surf ), meeting Alfred Stieglitz had the effect of activating, affirming, and intensifying White’s innate metaphorical disposition.(34)

White first encountered Stieglitz at An American Place, Stieglitz’s New York gallery, in February 1946. Their meeting was apparently strained at first, with White, just back from military service in the South Pacific, attempting to follow the great master as he elucidated his transcendentalist notion of Equivalence. White later recalled, “His talk itself was a kind of equivalent; that is, his words were not related to the sense he was making.” Finally Stieglitz said something that hit a nerve: “Have you ever been in love? . . .Then you can photograph.”(35) Equivalence, as articulated by Stieglitz—a subordination of the photograph’s literal subject matter in favor of a metaphorical reading—captured White’s imagination, allowing him to channel feelings into an established language of photography that was at once widely understood and ripe for multiple entendre. Equivalence, White later wrote, granted him “freedom from the tyranny of ecstasy.”(36) It allowed him to reveal the full strength and tenor of his emotions under the guise of a formalist tradition as set forth by Stieglitz, Weston, and Ansel Adams.

White borrowed a second concept from Stieglitz: the Sequence. But he added a crucial twist. While Stieglitz had conceived of sequenced photographs as an ordering of abstract elements, as in music, White’s sequences offered faintly limned, evocative narratives, similar in structure to free-verse poetry. Although most critics, both then and now, never really warmed to the idea,White considered his approach to this form one of his most important innovations.(37) The sequence seems to have gratified an important psychological need for White, especially after his 1953 move to the colder, more repressed climes of Rochester, where mysticism began to fill the void left after his youthful West Coast dalliances. Already in 1952, White states that “the camera must report a revitalization. It must revitalize an experience.”(38) Here White is invoking photography’s capacity to stop and preserve time, but he is also referring to a specific set of experiences he has left behind and has little hope of repeating. In that sense, the sequences are both souvenir albums and narrative evocations.

For example, White’s The Temptation of Saint Anthony Is Mirrors of 1948, compiled as a hand-bound volume with images paired on facing pages—“mirrors” to both one another and the artist—is a personal account as well as a meditation on the sins of the flesh.

Temptation (which was never published or exhibited) begins with a sort of prologue, comprising a single full-length nude of Tom Murphy, White’s student and the model most commonly associated with his work. The pose is similar to those found in the beefcake pictures White was producing at this time: Murphy adopts a classical contrapposto stance and is entirely nude, his pale, wiry body positioned against a dark backdrop. A piece of driftwood at the model’s feet proposes a theme of innocence—man in his natural state. The sequence then moves to pairings of images describing man in his civilized state, featuring several loving close-ups of Murphy’s gesturing hands,a shot of his bare feet, and a single shoulder-length portrait, in which he wears a buttoned shirt and looks intently off to the side. Next, there is an interlude suggesting growing dissolution: an image of Murphy’s feet and a petrified stone is paired with a shot of Murphy in full dress slouched on a mass of rocks and staring vacantly off into the distance. The next pairing accelerates the descent into temptation. Here, the pose in a second picture of Murphy’s feet suggests agitation, while a three-quarter-length portrait of Murphy, crouched in the bushes and looking back over his shoulder, is as emblematic an image of cruising as White ever produced. The photographs that follow descend further into lust and self-recrimination, conveyed through photographs in which Murphy’s naked body alternates between expressions of pain and pleasure.(39) The sequence ends with a series of beatific nudes, which express redemption through nonsexual treatments of the body and in the body’s juxtaposition with natural forms—a return to nature.

White may have thought at first that the sequence format would help him transcend the limits of personal biography, that he could use the breadth and fluidity of the sequence to emphasize a universal narrative while exercising control over the potentially explosive and revealing content of individual images.(40) This proved to be overly optimistic, at least in his earliest uses of the form. White’s colleagues, for example, immediately understood Temptation for what it really was: an agonized portrayal of White’s love for his male student.

This response drove White toward abstraction. The Fourth Sequence, completed in 1950, was White’s most abstract sequence to date, yet it was abstract in the same way that Stieglitz’s Equivalents were abstract, comprising isolated elements of recognizable natural phenomena. Many of the pictures used in this work were taken around the same time that White was photographing Murphy, and the resemblance between the contours of the stone, punctuated by dimple-like depressions, and Murphy’s body, particularly his distinctive navel, was hardly coincidental. Not surprisingly, this sequence, too, was recognized by White’s colleagues as being highly erotic and revealing of the photographer’s tormented personal life.(41) Another sequence from this period, Amputations (completed in 1947), which was slated for exhibition at the California Palace of the Legion of Honor in San Francisco, proved to be problematic as well. The show was canceled, purportedly due to a squabble over the quality of White’s poetry (which he insisted on including), but it may have been more a question of the content of the poetry, which sentimentalized the deaths of White’s army buddies, one of whom is pictured shirtless. The series also included several nudes of Tom Murphy.(42)

In 1953, on the eve of White’s move to Rochester and full conversion to mysticism, the photographer wrote a lengthy, self-consciously philosophical letter to the photo-historian Helmut Gernsheim. In it, White spoke presciently of transformation: “The thin red line of uniqueness for me is concerned with metamorphosis. With change, with the transitory, the plurality of meanings—I am enraptured with transformations.”(43) White’s most recent photographs had taken him beyond the specific erotic fixations glimpsed in Temptation, Fourth Sequence, and Amputations, delivering him to higher artistic ground. In 1951, as turmoil over those series abated, White met a dancer named William Smith. Smith, who became the subject of Sequence 11/The Young Man as Mystic (completed in 1955), was graceful and shared White’s rarefied feelings for aesthetic order.(44) He also introduced White to Christian mysticism.

It is fascinating to observe White’s handling of Smith in this group of negatives. White directs his model through a variety of scenarios, from loitering in urban dockyards to dreaming in nature, culminating in pictures of Smith nude, wandering among rock formations on the beach. In other words, Sequence 11 posits in perfect linear fashion the displacement of cruising by a universalized mystical searching—sexual longing setting in motion a heroic search. And while the ostensible point of this search was transcendence, glimpsed perhaps in fleeting moments of aesthetic reverie, for White the search itself seems to have become the acknowledged purpose of his actions. Banqueting on frustration had accustomed him to an acceptance of uncertainty and open-endedness—a state of constant, unresolved longing—which his readings in various religions affirmed. In that sense, White’s quest for transformation remained just that: a quest, extended through series of photographs, unresolved until the end.

Whatever solace White found in universalizing his personal experience through photography, the end result seems to have been more compensatory than redemptive. Already in 1951, White acknowledged the failure of photography as a path toward salvation, writing that the “camera is both a way of life and not enough to live by.”(45) To this disappointment, one might add that the mystic’s approach was no model for photography’s future. White’s plight had motivated an aesthetic theory, which in turn stumbled across concepts germane to photographic thought after modernism—namely, the plurality of meaning and its dependence upon context. But these notions, in their future manifestations, would jump the fence of internalized experience. Pop art and the glossy fabrications of the “Pictures Generation” artists dispensed with the obsessive yearnings of the individual, focusing instead on the individual’s place in the larger, media-saturated culture. Irony, playing off the notion of photography’s apparent promise of certainty, would fare much better as a theoretical disposition.

“The photograph as dream”: not White’s most precise pronouncement on photography but possibly the most salient to his own work, given the breadth of his concerns.(46) White wanted too much from photography; he wanted it to work as a guidebook, a therapy, a lover, a religion. Most of all, he wanted connection through photography, an affirmation that he and others could communicate clearly and freely about all that mattered. He wanted to be a realist—but he was not. He was a romantic, compelled to create images such as Untitled (Man and vertical surf ) (1951), in which meanings are obscured, not clarified; signs are effaced, not illuminated; beauty is closeted, not set out for all to see. White was attracted to the ambiguity of the dream because it offered cover and protection but also freedom to maneuver. The dream supported the irrational, maintained a sense of mystery, and beautified frustration. Most importantly, the dream conformed to the needs of the dreamer. For only in the dream could a world be conjured in which earth is sky, water is flame, and the eyes of an ideal lover look directly into one’s own.

***

Kevin Moore is an independent curator and writer based in New York. He is the author of Real to Real: Photographs from the Traina Collection (de Young Museum, San Francisco, 2012); and Starburst: Color Photography in America 1970–1980 (Cincinnati Art Museum, 2010).

This essay is reproduced with permission from the author as well as the Minor White Archive, Princeton University Art Museum. It originally appeared in More Than One: Photographs in Sequence, ed. Joel Smith (Princeton/New Haven: Princeton University Art Museum/Yale University Press, 2008).

NOTES

1. Minor White, “Memorable Fancies,” 1932–37; quoted in Peter C. Bunnell, Minor White: The Eye That Shapes (Princeton and Boston: The Art Museum, Princeton University; Bulfinch/Little, Brown, 1989), 19. 2. Minor White, Mirrors, Messages, Manifestations (New York: Aperture, 1969), 15. 3. White described his feelings regarding his sexuality in a private diary entry dated March 30, 1960: “I have often said that for anyone who likes self pity—homosexuality is a grand source—and my response to it has been weeks of longing, recriminations for a few moments of pleasure. The rising intensity was enjoyable—and wrecked by intercourse, followed by weeks of name crying in the wind.” Quoted in Bunnell, Minor White, 37. 4. See, for example, Michael E. Hoffman’s “Preface to the Second Edition” of White, Mirrors (2d ed., New York: Aperture, 1982), n.p. 5. William V. Ganis offers an intriguing interpretation of “straight photography” in relation to Andy Warhol’s work, relating certain “straight” subjects to photographers such as Ansel Adams and Edward Weston (the American landscape, the female nude) and arguing that straight photography implies “a visual truth paradigm,” showing things “for what they are” and not, as in White’s phrase, “for what else they are.” Ganis, Andy Warhol’s Serial Photography (Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 2004), 101–2. 6. Bunnell, Minor White, 20. 7. See the chapter on Frank in Blake Stimson, The Pivot of the World: Photography and Its Nation (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2006). 8. See the Chronology in Bunnell, Minor White, 2–3. 9. In the Image Chronology section of Mirrors, Messages, Manifestations, White writes that he was instructed by the WPA “to document by nostalgia, to try to evoke the sense of pride Portlanders sixty years ago must have felt in their new city.” To achieve this, White photographed on Saturday afternoons and Sunday mornings, “when the cars and trolleys with their 1938 and 1939 license plates were off the streets”; nonetheless, many of the pictures from this series include people and vehicles. White, Mirrors, 225. 10. White was also making publicity photographs for the Portland Civic Theater at this time. The fact that his subject is posed in two different doorways suggests the possibility that this is an actor and the scenario was contrived. Rather than changing my reading of the images, this possibility only adds another stratum of coded meaning: actor as laborer as cruising homosexual. Joel Eisinger derives the title of his book on modernist photographic criticism from White’s framing of the “paradox of trace and transformation.” See Eisinger on White, Trace and Transformation: American Criticism of Photography in the Modernist Period (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1995), 143–67. 11. White’s manuscript for this essay was completed in 1953 but never published. Bunnell, Minor White, 16–17. 12. Peter Bunnell characterizes White’s San Francisco period (1946–53) as a time of “observation,” during which he produced photographs that were, generally speaking, more spontaneous, less directed, and less personal. Ibid., 51–52. 13. The “Calamus” section of Leaves of Grass is considered the most overtly homosexual passage of the collection. See Francis Murphy’s introduction in Walt Whitman: The Complete Poems (London: Penguin, 2004), xxxii–xxxiii. 14. Ibid., 158. 15. Mark W. Turner, Backward Glances: Cruising the Queer Streets of New York and London (London: Reaktion, 2003), 18. 16. In “The Crowds,” Baudelaire tells us that he simply entered at will into the character of individuals encountered on the street. “For [the poet] alone,” he continues, “everything is vacant; and if certain places appear to be closed to him, that is because in his eyes they are not worth the bother of visiting. The solitary and pensive stroller finds this universal communion extraordinarily intoxicating.” Quoted in ibid., 18. 17. Robert L. Herbert, Impressionism: Art, Leisure, and Parisian Society (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988), 33. 18. Turner, Backward Glances, 60. 19. In Turner’s summation, to “queer history” is to present counterdiscourses that disrupt the literature on modernism. “Disruption is the key to understanding the queer critical term.” Turner, Backward Glances, 43. Bunnell characterizes White as the inheritor of the Stieglitz-Weston legacy, carrying their formalism to the level of metaphor. See Bunnell, Minor White, 15. 20. In “Varieties of Responses to Photographs,” published in Aperture in 1962, White admits that a viewer’s response to a given photograph “is true of himself, but not necessarily true of the picture in spite of the fact that it was the photograph in question that aroused his reaction.” Quoted in Eisinger, Trace and Transformation, 160. On White’s critical thought and his flirtation with post-Structuralism in particular, see ibid., 158–61. 21. Many of these pictures remained unseen until the publication of Brassaï’s The Secret Paris of the ’30s (New York: Pantheon, 1976). 22. See Anne Wilkes Tucker, Brassaï: The Eye of Paris (Houston and New York: Museum of Fine Arts; Abrams, 1998), 78. 23. Quoted in Bunnell, Minor White, 18. 24. See F. Valentine Hooven III, Beefcake: The Muscle Magazines of America, 1950–1970 (Cologne: Taschen, 1995). 25. The best general study of this subject is Emmanuel Cooper, Fully Exposed: The Male Nude in Photography (London: Unwin Hyman, 1990). For a recent French perspective, see Pierre Borhan, Man to Man: A History of Gay Photography (New York: Abrams, 2007). 26. Peter Bunnell says that White was sexually voracious during this period of his life—he was in his thirties—but that when he moved to Rochester in 1953 he decided that it was time to “shut it down.” Conversation with Bunnell, spring 2008. 27. Later in the same letter, White refers to Weston’s “sex symbols” and takes this observation one step further, elevating Weston’s acknowledgment of sex as a source of regeneration and creativity to an acknowledgment of “He who is the creator of sex.” White, letter to Adams, March 8, 1947, in Bunnell, Minor White, 25. 28. “Memorable Fancies,” March 22, 1960, in ibid., 38. 29. Bunnell reproduces the entire letter in the Unpublished Writings section of his Minor White. “Letter to a photographer,” November 1, 1962, in ibid., 39–40. 30. Ibid. 31. Peter Bunnell notes that, although White did not publish these photographs or certain passages from his private papers dealing with his homosexuality, neither did he destroy these materials; on the contrary, he included them in his donation to Princeton, presumably with the understanding that they would be useful to scholars after his death. Ibid., 21. 32. Ibid., 17–18. 33. For Day, who photographed nude and semi-nude young men in an earlier era, the challenge was of course more complex. On that artist’s navigation of the sexual mores and aesthetic conventions of his period, see James Crump, F. Holland Day: Suffering the Ideal (Santa Fe: Twin Palms, 1995). 34. White wrote in 1947, “Camera will lead my constant introspection back into the world.” White, Mirrors, 190. 35. Ibid., 41. 36. White, “Memorable Fancies,” 1966, in ibid. 37. John Szarkowski, for example, ignored White’s interest in metaphor, his use of the sequence, and the whole of his photographic criticism, instead aligning White’s pictures with his own vision of photography; he called White’s best pictures “frank and open records of discovery.” Quoted in Eisinger, Trace and Transformation, 218. 38. White, “Memorable Fancies,” December 31, 1952; quoted in Bunnell, Minor White, 29. 39. Peter Bunnell notes, in reference to a picture of Murphy gripping his torso, an image suggesting both masturbation and torment, that it “reflects simultaneously extremes of emotion that are almost opposite in character.” Bunnell, Minor White, 50. 40. Jonathan Weinberg makes a similar point in his study of works by Charles Demuth and Marsden Hartley. Weinberg, Speaking for Vice: Homosexuality in the Art of Charles Demuth, Marsden Hartley, and the First American Avant-Garde (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1993), 32. 41. Bunnell, Minor White, 6. 42. White included Amputations in his monograph Mirrors, 32–39. 43. White, letter to Helmut Gernsheim, September 4, 1953; reproduced in Bunnell, Minor White, 29–30. 44. White described Smith as “a lad who had a near direct line to spirit.” Ibid., 33. 45. White, Mirrors, 190. 46. White, “Memorable Fancies,” March 10, 1957; quoted in Bunnell, Minor White, 34. Joel Eisinger notes that White’s critical confusion made him “invulnerable to disagreement.” Eisinger, Trace and Transformation, 167.