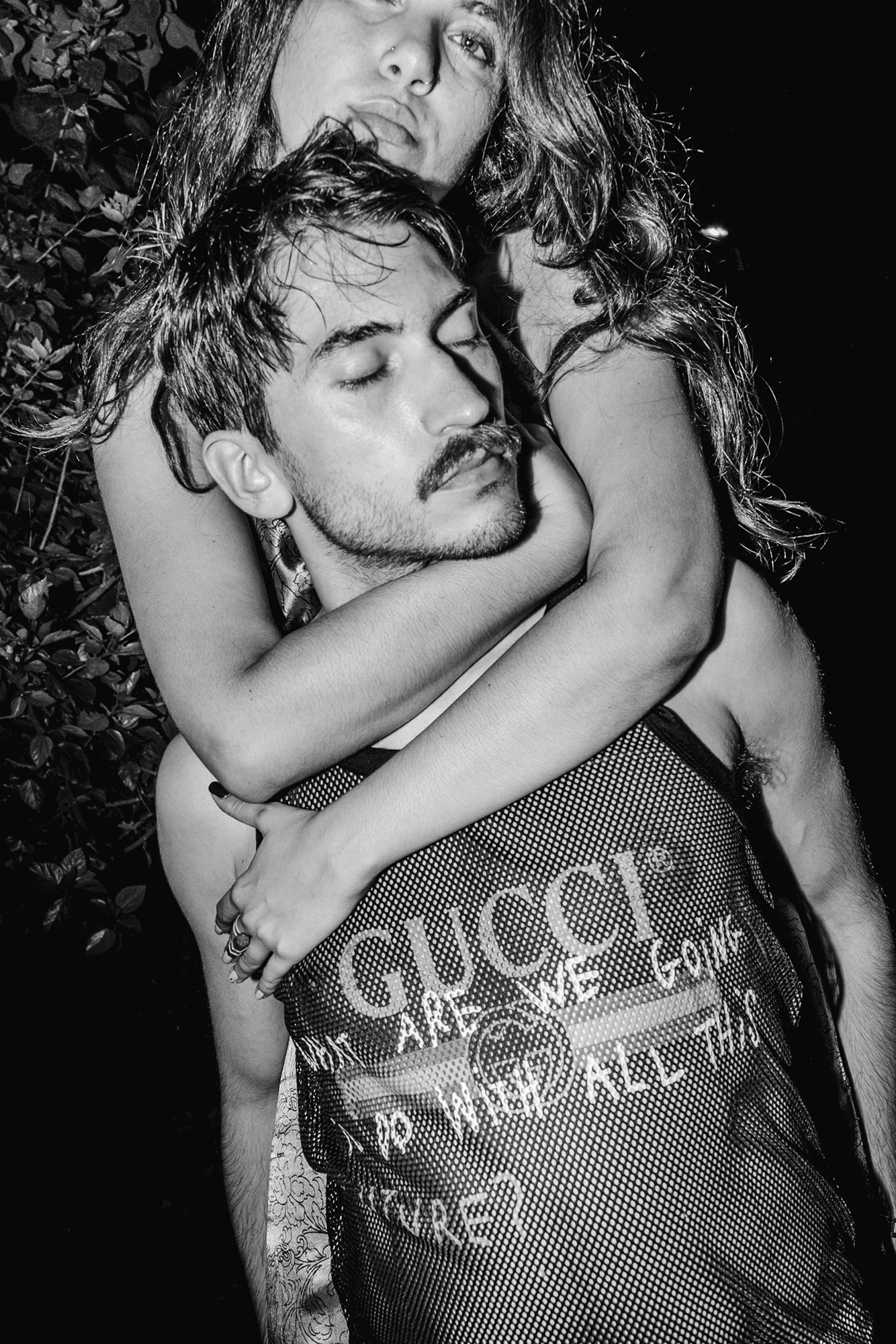

Myriam Boulos, Untitled, Beirut, Lebanon, November 2017–August 2020

“Reach out and touch faith,” Depeche Mode implored in “Personal Jesus.” In Myriam Boulos’s photographs, I could’ve sworn I heard her subjects whisper, “Reach out and touch me.”

Faith is touch; touch is sacred. And the body is its own god.

Against a purple sky, two naked men tenderly embrace; one is, indeed, whispering, not to us the welcome voyeurs—but into the ear of his beloved. Juxtapose the delicacy of that moment—men stripped of the confines that patriarchy makes of masculinity—with the altogether more robust, and much more tightly cropped, image of two women kissing. Swallowing each other whole, more like. It is difficult to ascertain where one begins and the other ends. There is power in their desire.

And that is what the revolution renders: powerful women and tender men.

In a global pandemic that has starved us of touch, who would not genuflect before the heady carnality captured by Boulos’s gaze? In almost every photograph in her series What’s Ours (2019–ongoing), hands knead into flesh, skin lies on top of skin, body hair on disjointed limbs serves like rivers on a map, luring us closer toward sustenance, enticing us with intimacy, destination freedom.

Boulos was born in 1992, in Lebanon, two years after the official end of the seventeen-year civil war. Her fluency for turning her country inside out with her gaze has landed her work in Vanity Fair, Vogue, and Time. She is based in Beirut, but she was in Paris on a two-month fellowship when we spoke last year.

Reflecting on What’s Ours, Boulous has written that when the revolution began in Lebanon in October 2019, with protests against corruption and austerity measures, “It all felt as if we were coming out of an abusive relationship to finally say: No, this is not normal.”

Those who truly want to be free know that is how the revolution succeeds. The revolution against the political tyrant alone is the minor one. Taking a leader down does little to topple the personal tyrants who live on street corners, in our bedrooms, in our minds. Their overthrow is the stuff of major revolution.

Who does the revolution belong to? What do we own if not our bodies? What is ours?

“My friends and I used to take pictures naked in the streets of Beirut,” Boulos writes. “It was our own way of reclaiming our streets and our bodies. Everything that is supposed to be ours.”

The inhabitants of Boulos’s Beirut clearly trust her. Obsessed as she tells me she is with “the body and the present moment,” it is as if she has stepped inside the embrace that she captures, presenting it to us with awe and reverence; as if she sliced through the thin veil that separates the “us” from the “them” and entered the embrace on another, ethereal level that does not disturb or distract the divine creatures she captures.

Her eyes, heart, and camera are the holy trinity.

“A revolution was happening in my country, a revolution was happening in me. It made me question everything,” Boulos writes. Revolutions—I know as an Egyptian marking ten years since my country’s revolution—inspire you to say no to more, to everyone. One “no” leads to another like a stairway to liberation. When that staircase is yanked, you take a vulnerable punch to the gut. In Lebanon, a financial crisis, the pandemic, and the Beirut port explosion of August 2020 did not just yank at the staircase to liberation but seemed to fray it to bits.

“Since the explosion, I feel like a glass of water that overflows constantly,” Boulos writes.

In a Zoom chat—she in Paris, I in Montreal—we talk about the leitmotif of compounded trauma and unresolved grief that connects our parts of the Middle East. And we talk about the body’s need to fuck to mark its survival. She tells me of post-Beirut port explosion sex with an ex. I am reminded of how, soon after Egyptian riot police broke both my arms and sexually assaulted me in 2011, I began an on-again, off-again entanglement with a survivor of a postrevolution massacre in Egypt.

“An acute awareness of our mortality makes the physical especially important,” I tell her. “This is your body saying to you, You are alive, and you have to do what you’re meant to do, and that is fuck. Do it now!”

I am delighted that her new project is on women’s sexual fantasies.

Faith is touch; touch is sacred. And the body is its own god. We are each other’s personal saviors because, as the poet and activist June Jordan wrote in her 1978 Poem for South African Women, “We are the ones we have been waiting for.”

Courtesy the artist

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 246, “Celebrations,” under the title “What’s Ours.”