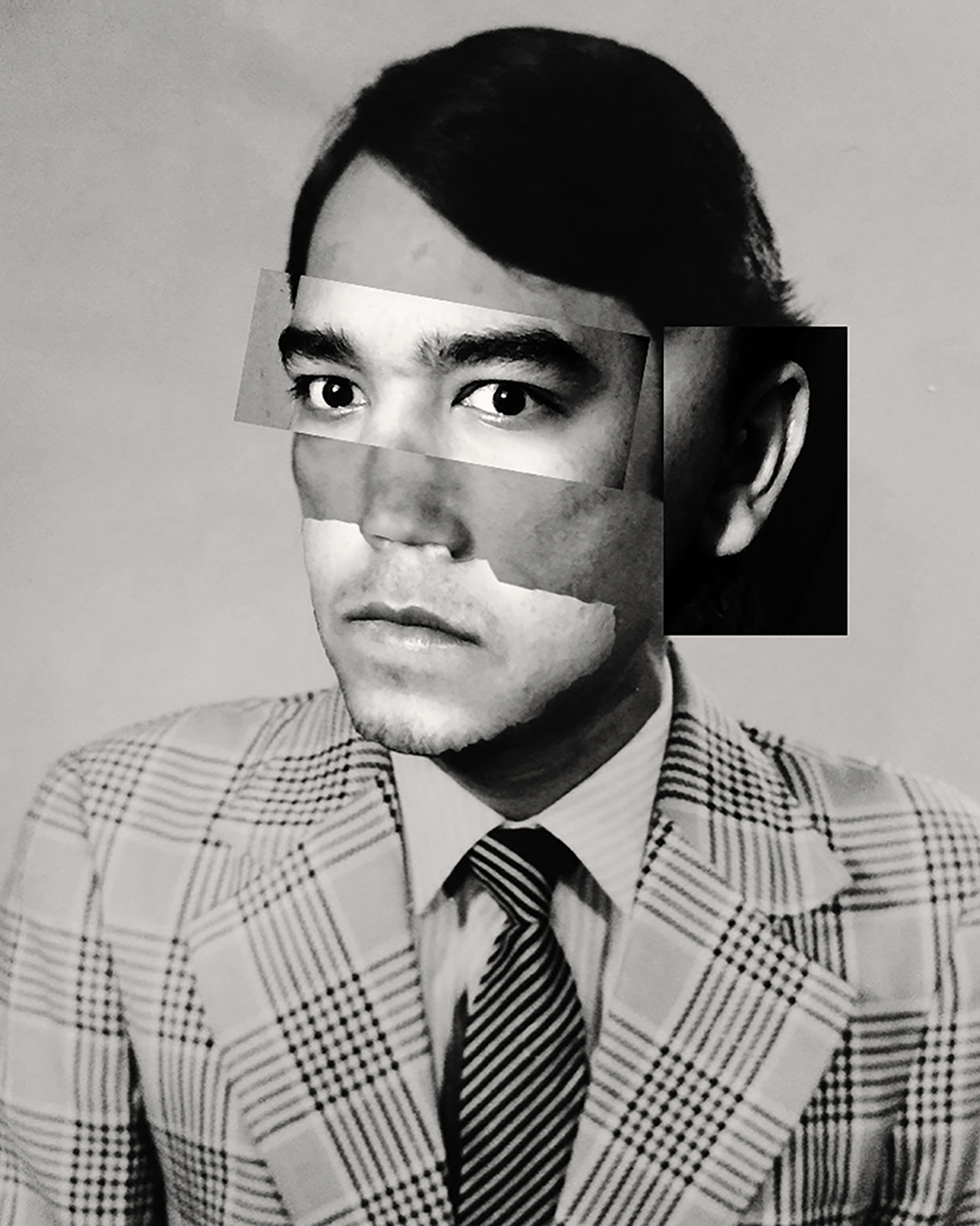

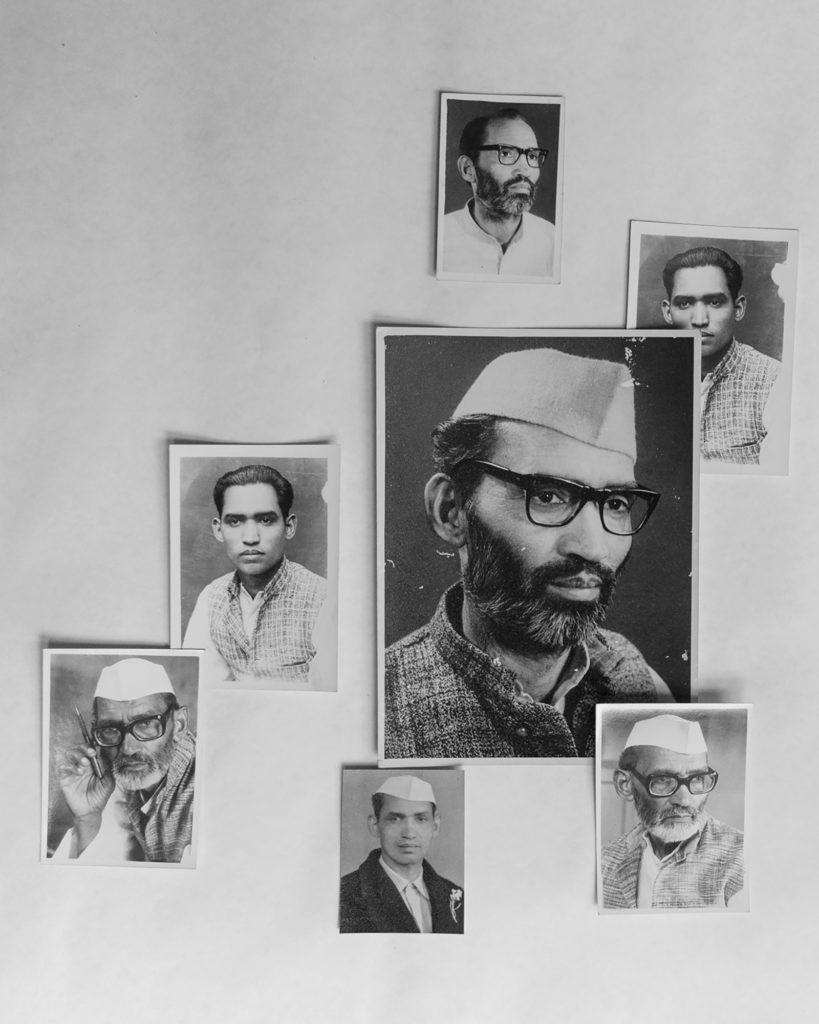

Devashish Gaur, Me and Dad; thinking of how much of our personalities can we rub onto each other before we start seeing each other in each other? How long can we stay our true selves when we share the same domestic space for so long?, 2019

The New Delhi–based photographer Devashish Gaur’s series This Is the Closest We Will Get (2019–ongoing) was sparked by the chance discovery of photographs of his grandfather during the renovation of their family home. “The title is derived from the limitations around knowing someone who doesn’t exist anymore,” Gaur says. “There will always be a certain distance. The gap between generations is one that can’t be altogether diminished.” Arising partly out of his curiosity about the life and persona of his grandfather, and partly from his urge to better understand his own somewhat strained relationship with his father, the series poses an intergenerational dialogue between individuals, objects, and beliefs. This Is the Closest We Will Get is among the winners of the Vantage Point Sharjah prize from the Sharjah Art Foundation, where the series is currently on view through December 18, 2021.

Gaur curates his narratives by combining old photographs requisitioned from family albums, archives, and vintage shops onto which the by-lanes of Delhi abruptly descend, with fresh documentation from his research. A number of his past projects are steeped in nostalgia, excavating material memory to reconstruct the notion of home and coalescing intimacies of different kinds—corporeal, social, or spatial. The slow-evolving continuities of domestic dispositions betray traces of the rapidly shifting backdrop of public life. One gets the uncanny sense that Gaur’s mundane and somewhat outmoded subjects—like the last glass of homemade ice cream waiting in the freezer—are holding still for a time-lapse as the world around them streaks forth at the speed of technology.

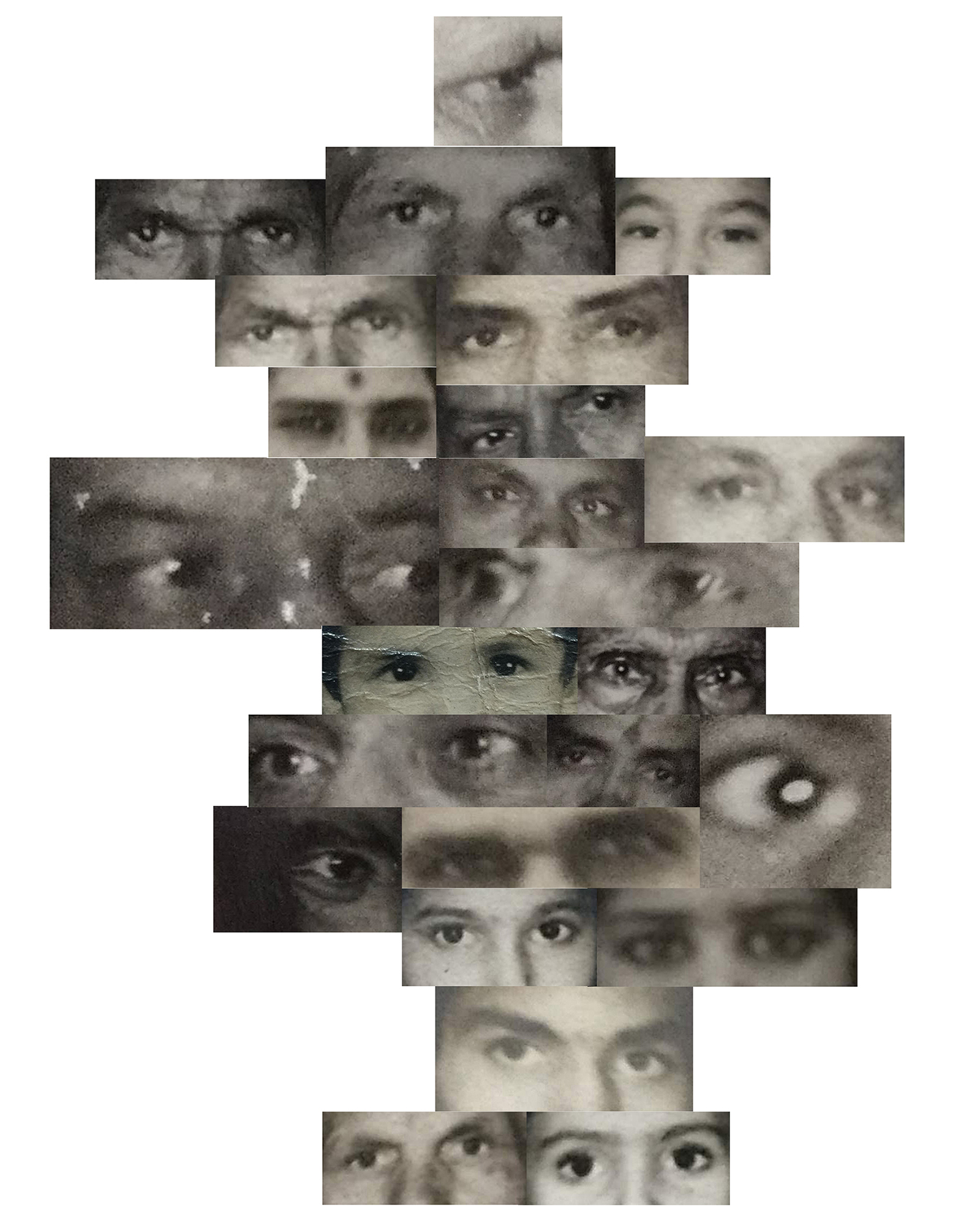

This is the Closest We Will Get assumes an ambiguous attitude toward surveillance. The many-eyed collage Witness of Existence (2019) exhibits Gaur’s desire to retro-vicariously surveil and inhabit the bodily dispositions of his grandfather, much like how the state surveils and inhabits the public behavior of its citizenry through CCTV cameras. Composed of multiple images cropped to eyes that once must have touched his grandfather, the work positions longing as a mode of “both belonging and ‘being long,’ or persisting over time,” to borrow Elizabeth Freeman’s words from her book Time Binds: Queer Temporalities, Queer Histories (2010).

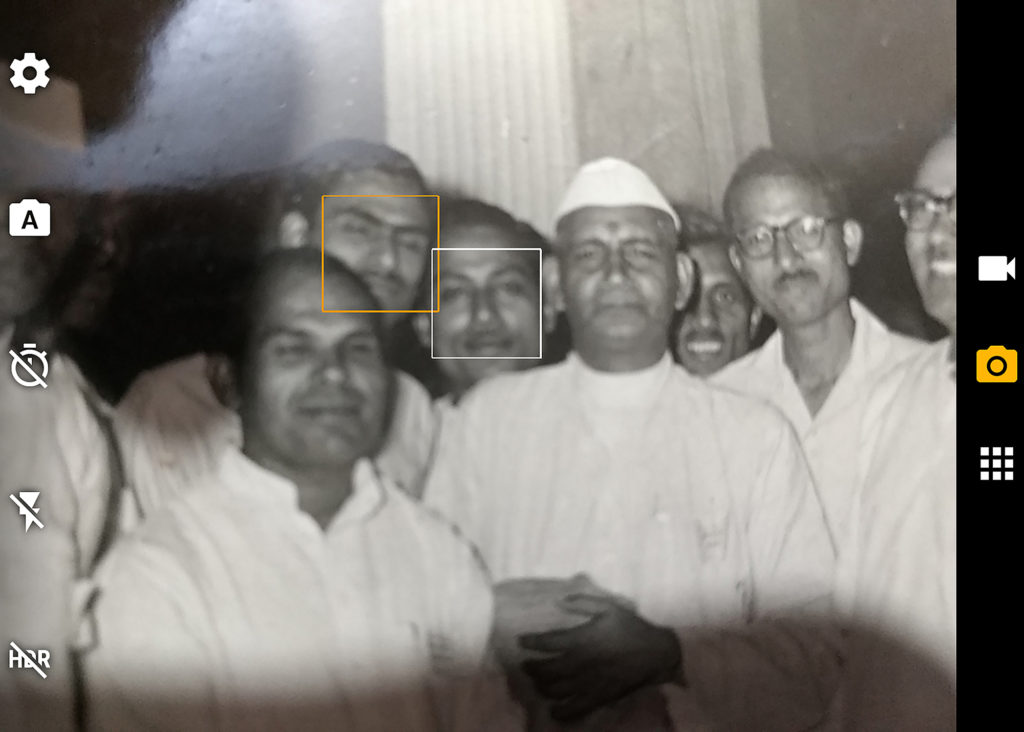

Gaur’s act of pointing a smartphone camera to these pre-smartphone pictures produces the curious anachronism of an AI trying to recognize faces that were never territorialized in this manner. The AI’s confused attempt at back-tracing these sovereign faces to nonexistent data-bodies prompts the following set of questions, encapsulated in the work’s title: How much can the software know? How much meaning is lost in face detection? And how many memories are forever gone? In addition to resurrecting modes of parenting and past traumas, Gaur’s ghosting-in-reverse critiques the recent bids by the Indian government for greater biopolitical control through state-run registers of citizen data. In the most surveilled city in the world, pointing a smartphone camera to an unyielding picture becomes a symbolic act of defiance.

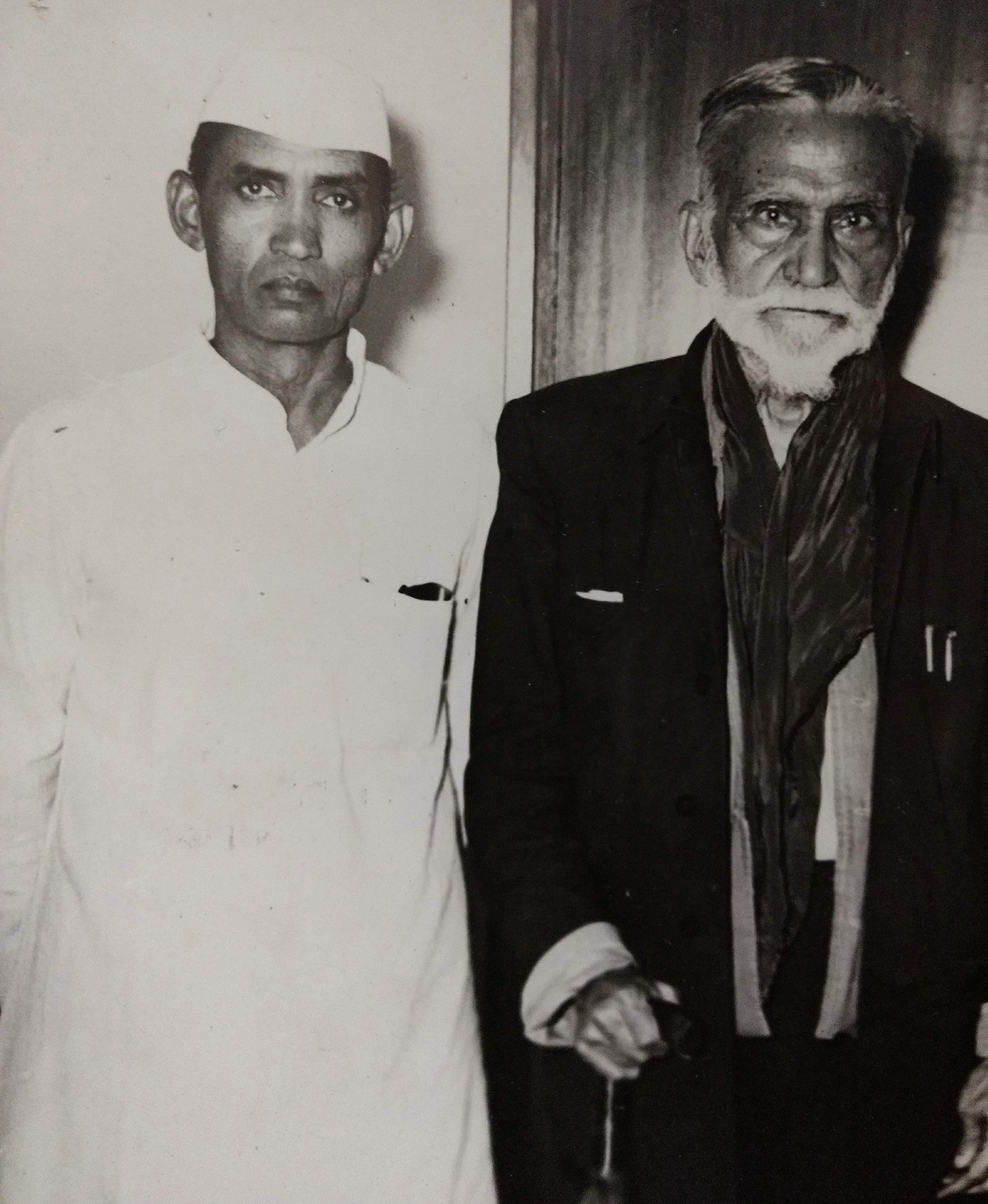

The subjects of This is the Closest We Will Get tease oedipal dialectics. In Dad dressing up as Grandpa (2020) the uncharacteristic desire of Gaur’s camera-shy father to be photographed for his social media intersects with his late grandfather’s habit of posing regularly for his friends’ cameras. We don’t know whether or not the choice of donning the white Gandhi cap, like Gaur’s grandfather used to, is conscious, but the correspondence is tantalizing. If these framings help the artist imagine what kind of relationship existed between his father and his grandfather, collages like Me and Dad (2019) hit closer to home. Composed of bits of Gaur’s own portrait overlaid with that of his father’s, the work speculates, queerly, about the commingling of personalities from the standpoint of prolonged proximity, not genealogy.

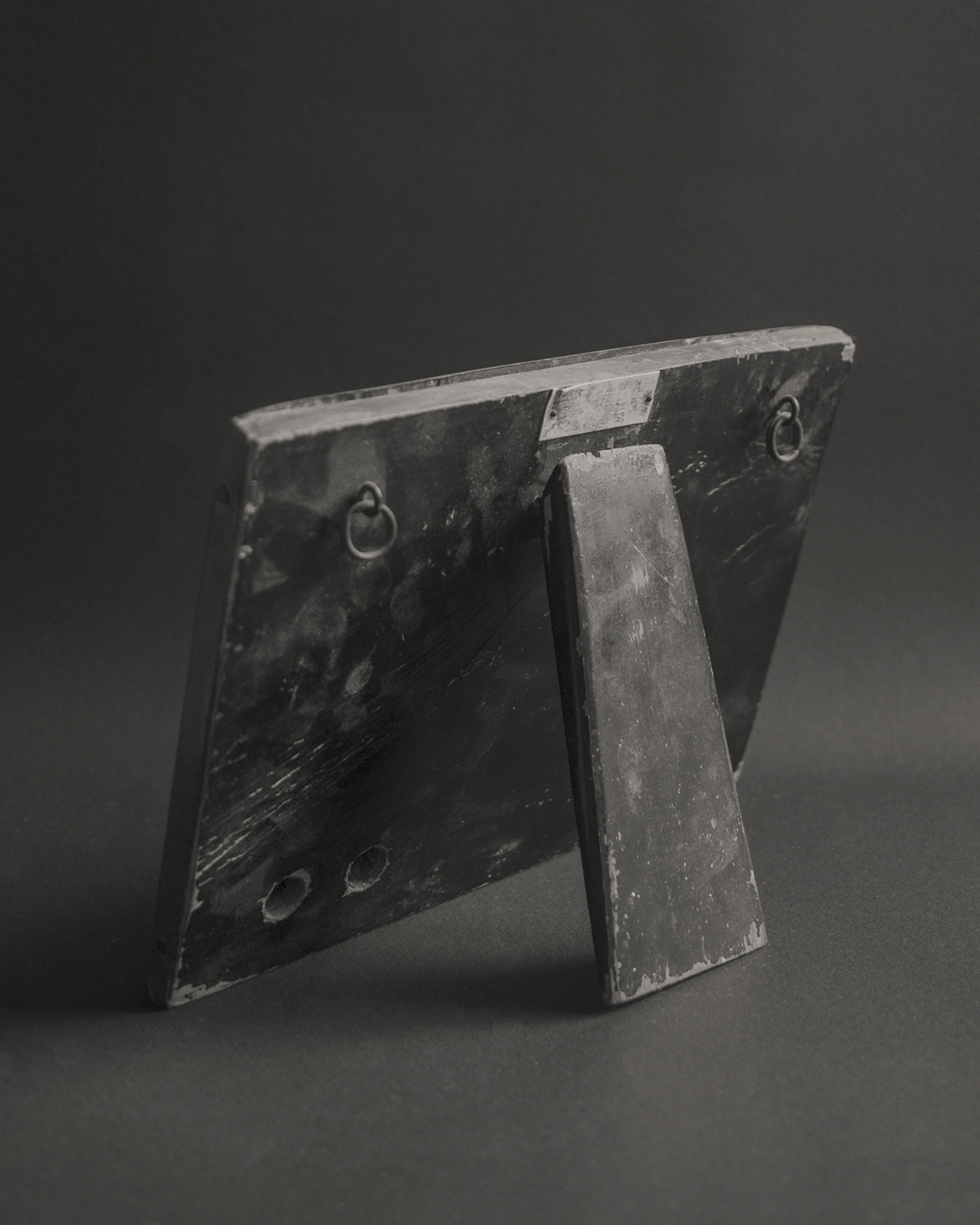

Elsewhere, the tamrapatra (copper plate) awarded to Gaur’s grandfather for his contributions to India’s struggle for independence, photographed from behind, seems to gently mock the precious freedom that was fought for. “I was told that my grandfather wasn’t a religious person,” Gaur says. Referring to the chance discovery of a forsaken image of the popular saint, Sai Baba, in a riverbed, he adds: “A religious icon that was once worshipped and took up space in someone’s house is now left behind. I think my grandfather would laugh at the absurdity of this cycle from adoration to obsolescence and abandonment.” This fate is echoed by a small votive of Shani Dev (Saturn) that Gaur’s father once worshipped and now lies neglected somewhere in the house, gesturing toward the rising tide of right-wing conservatism in a country that no longer sees faith as innocent.

The black-and-white photograph of a splotchy old pillow beckons with the knowledge of untold mysteries. Titled after a Dean Martin song, Pillow that you dream on (2020), the photograph not only expresses a wish for a more intimate relation with a reticent father but also delineates a broader search for softness within masculinist cultures. As Gaur observes, “details about how people held each other, sat with a certain elegance—placing hands on their legs while sitting—signal rare beauty and delicateness sanctioned to masculinity.” When lips are silent, pillows can talk a great deal.

All photographs from the series This Is the Closest We Will Get, 2019–ongoing. Courtesy the artist

Read more from our series “Introducing,” which highlights exciting new voices in photography.