On Travess Smalley's Capture Physical Presence

Travess Smalley is a wonderful assembler. He pans and sifts like a digital prospector through the detritus of the computer screen, gleaning golden kernels of information that he recombines into images. He makes vibrantly colorful videos and digital prints—sometimes on paper, other times on silk, velvet, or vinyl. He creates works for web browsers, too; ultimately, he chooses whatever material or medium is most congenial to the particular strategy at hand. Smalley has a very intuitive and playful approach to imaging technology. His most recent work is based upon using the flatbed scanner as a creative tool. He applies to objects he scans a host of digital mark-making techniques, referencing modernist painting, 1990s-era digital culture, and the spuriously broad category of post-Internet art.

When I met Smalley in Chelsea recently, I mentioned James Welling’s distinction between pictures formed by a lens and images with a more immaterial provenance. It seemed to me that such a distinction is not particularly relevant to Smalley’s work. “I agree,” he said. “And neither is the distinction between photography and painting.” He continued, “In a recent interview Wolfgang Tillmans mentioned how he thinks of his photographs like paintings, and Gerhard Richter is using Photoshop to clone and mirror sections of his canvases, even though he still speaks of them as traditional paintings.” I asked Smalley whether the “photography” in his montage-like work is in the scanner used to capture the images. “Totally,” he responded. “It’s just light—applied and then recorded.”

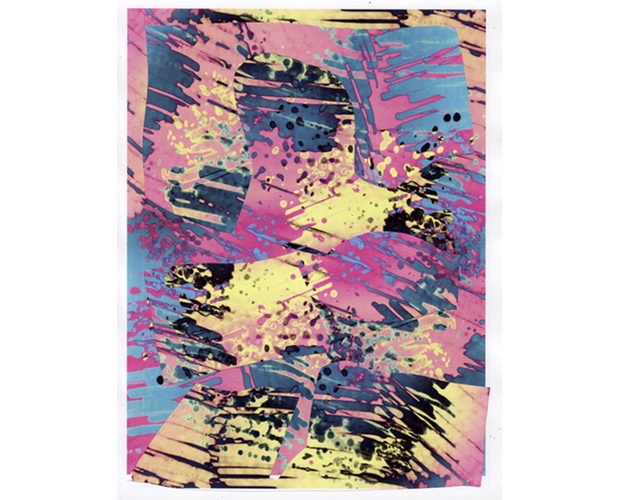

Smalley’s first New York solo show, titled Capture Physical Presence, is at Higher Pictures on the Upper East Side. The exhibition consists of six handsomely framed inkjet prints of photomontages that range from approximately thirty-by-forty inches to forty-by-fifty inches. In this body of work, Smalley creates computer graphics that he then prints out, cuts up, and rearranges before scanning them back into the computer for further modification. Higher Pictures has an impressive track record of offering solo shows to young artists: Sam Falls, Jessica Eaton, Artie Vierkant, and Letha Wilson have all had solo exhibitions there in the last three years, and it has presented influential group shows that serve as useful context for thinking about Smalley’s current exhibition.

Smalley’s work has a productive yet challenging relationship to photography. He does not use a camera. It is this distance that allows him to approach broader ontological questions: What is an image? How do images circulate within the technologies of contemporary culture? Smalley is interested in the physical quality of digital prints and the digital quality of physical things. The chance encounters he engenders between code and material also presciently forecast how technology is becoming increasingly entangled in both material and biological life. Smalley’s scalpel cuts mimic the vector tool of digital software; his deliberate degradation of gradients evokes halftone printing; and the printing and re-printing of inkjet prints misaligns and amplifies the invisible dot-matrix distribution of colors. Only two of the prints in the show have an even quadrilateral border. The rest have small protrusions that tug gently against the authority of the rectangle.

The abstract compositions in Capture Physical Presence are at once hurried and studied; they reflect the frenetic pace of screen-based productivity. Smalley diverts the quicker-faster-sharper attitude of networked image production into a more contemplative approach. The imperfections in Smalley’s process give his work an individual accessibility that is lost, for example, in Thomas Ruff’s epic photograms, recently exhibited in New York at David Zwirner. Ruff seems interested in digital tautologies that deceive the viewer into thinking they are analog; his photograms are created in a digital-imaging environment and then outputted with a simulated film grain that references silver-halide photography. Smalley instead veers towards intelligently fallacious syllogisms that falter in their logical coherence. It is these momentary losses of balance, this unease about slickness and perfection, that stymies the staid logic of digital information in his work.

The human scale and physical presence of Smalley’s works seem to resist the gravitational force of Tumblr and its daisy-chain of deauthored imagery. The sensation of standing in front of them is at once private and immersive, and the anti-reflective museum glass transmits all of the texture of the pigment prints. The scale feels like a close upright approximation of sitting in front of a desktop computer, yet the material qualities of the prints distinguishes them from the experience of the screen. As a case in point, while Smalley and I were chatting in the gallery he pulled out an iPad to show me more images from the twenty-five-strong series. We jokingly held up the high-resolution screen against a print for comparison, and I immediately recognized the difference between the flat pixels and the textured print, which had not been flush-mounted in its frame, allowing the paper to curl ever so slightly. These are the small pleasures that talented printmakers know how to appreciate and celebrate, however minute they might seem.

This year, Lorenzo Durantini will curate Debt & Riots at ProjectB and Syntax at the Museum for Contemporary Art MACRO, Rome. He reviewed a new book by David Benjamin Sherry for The PhotoBook Review Issue 004.