One of Photography’s Most Enigmatic Love Triangles Finally Gets Its Due

In their book “Body Language,” Nick Mauss and Angela Miller show how a group of artists shaped a network of queer image culture decades before Stonewall.

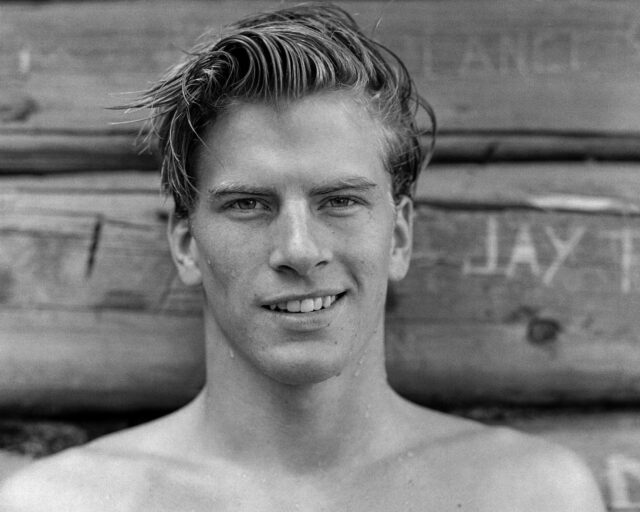

George Platt Lynes, Demus, 1937

Collections of the Kinsey Institute, Indiana University © Estate of George Platt Lynes

Nick Mauss and Angela Miller’s book Body Language: The Queer Staged Photographs of George Platt Lynes and PaJaMa (2023) brings new critical discourse to representations of queerness in American modernism. Part of a series called “Defining Moments in Photography,” the book contains two richly illustrated essays with an introduction by Anthony W. Lee. Mauss appraises the wide-ranging practice of George Platt Lynes, a photographer who is known (if at all) primarily for his male nudes from the 1930s and ’40s. Miller writes about the collaborative photographs of Paul Cadmus, Jared French, and Margaret Hoening French, who worked contemporaneously to Lynes under the moniker PaJaMa, a combination of their first names. Both essays explore the social roles these images played when circulated among a coterie of queer artists as well as their relationship to mass media, and how they not only informed other artworks made by their participants but also reflected a network of queer culture in America between the two world wars.

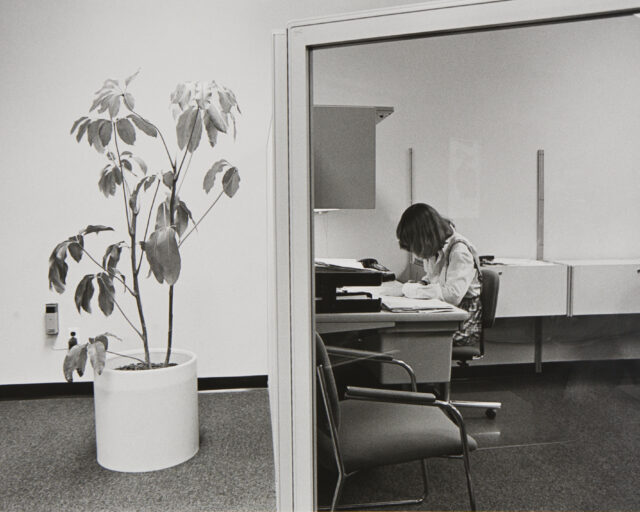

Angela Miller’s essay, “PaJaMa Drama,” is the first published piece of in-depth scholarly writing about the work of this landmark queer photography collaborative. PaJaMa made highly staged figurative photographs on the beach in queer havens such as Fire Island and Provincetown, Massachusetts; in the apartments of friends in New York’s Greenwich Village; and later on the shores of Nantucket. Their collaboration started in 1937, and they produced thousands of negatives of staged tableaux, working as a formal collective through 1955, though they informally photographed each other for the rest of their lives, into the 1980s. The pictures were not created for exhibition but were instead “gift images” circulated among friends, sent in letters, and handed out at dinner parties. They were also used as reference images for paintings. Significantly, the label PaJaMa was applied only to the collaborative images by Cadmus, the most famous artist of the trio, when the pictures were first exhibited in the 1970s. Both Margaret and Jared hated the name.

Courtesy DC Moore Gallery, New York

The pictures dramatize the complex dynamics between the collaborators. Paul Cadmus and Jared French had been deeply involved romantically for eight years before Jared married Margaret French in 1937, and they remained so afterward. Margaret came from a moneyed New Jersey family; she was devoted to Jared and supported him financially. Margaret and Paul had a “loving if guarded” friendship, Miller writes, because they were both in love with Jared. Today, we might describe this as polyamory, but within PaJaMa’s network of friends and lovers, a kind of freedom existed in the lack of labels and sexual categories, in the unnamed nature of things.

For Miller, the photographs, which are often foreboding in their sense of light and always statuesque in composition, provided still points of mooring amid their tempestuous and fluid personal lives. She attributes the recurring motif of a doubled, shadowed self in the photographs to Jared French’s interest in Jungian archetypes and the dual sides of anima and animus. Miller also argues that the members of PaJaMa were influenced by the aesthetics of 1940s Hollywood film noir and, in particular, melodrama. Reading Miller’s list of citations shows the new ground she is tilling. She cites auction catalogs, newspaper reviews of the relatively small number of exhibitions of PaJaMa’s work, and websites, in addition to the extensive correspondence and personal papers that Cadmus and the Frenches left to Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library and the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

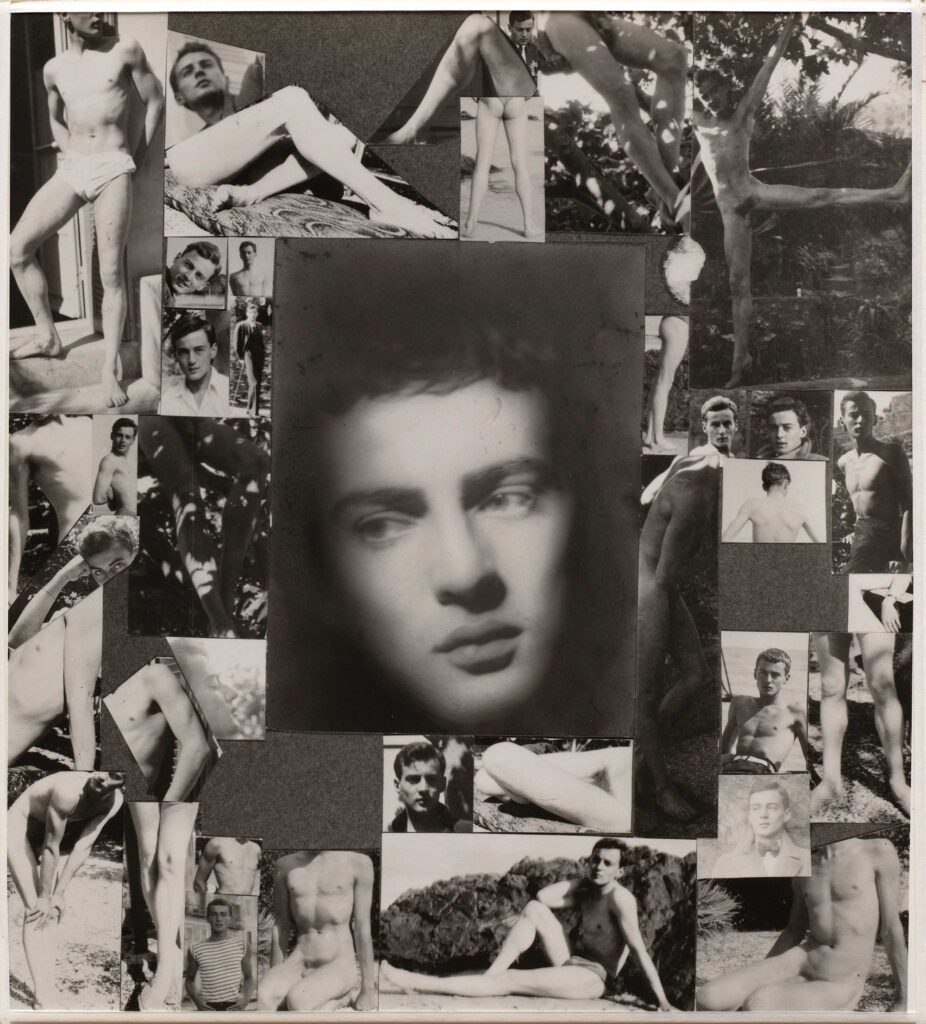

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York © Estate of George Platt Lynes

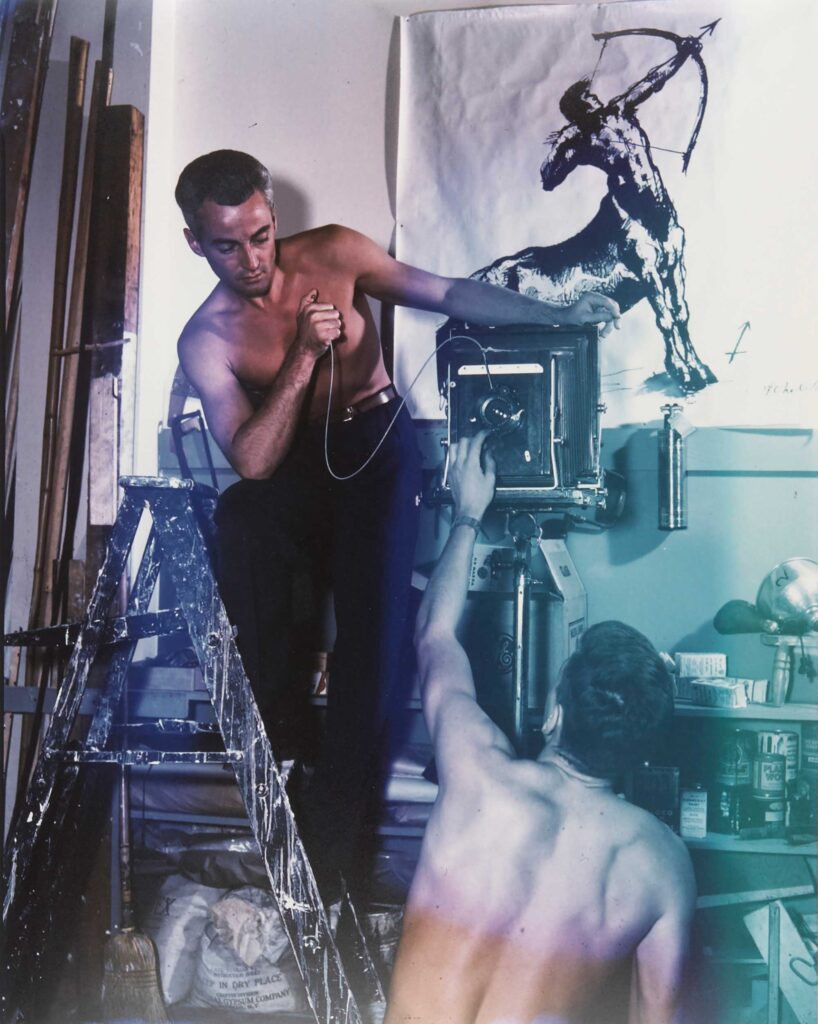

Nick Mauss is a visual artist and writer whose 2018 exhibition Transmissions at the Whitney Museum in New York featured photographs by Lynes and PaJaMa. In his essay, “The Uses of Photographs,” he discusses the multiple ways that George Platt Lynes’s photographs circulated, both publicly and privately. He maps the intertwined nature of Lynes’s practices as a portraitist, a photographer of fashion and dance, and an enthusiastic proponent of the male nude. Mauss’s research provides a counterpoint to the publications released by Twelvetrees Press between 1981 and 1994 that introduced Lynes’s work to a broad audience, but which silo his artistic production into three separate artistic genres. But Mauss’s research goes beyond these sources, examining the staggering wealth of archival material Lynes left behind in the form of correspondence, personal scrapbooks, and printed ephemera, making connections that are unique to a visual artist’s sensibility. To connect the dots, he also includes the work Lynes did not want to leave behind—his fashion photographs, which he begrudgingly made for a living and tried to destroy by burning the negatives before his death. Thankfully for Mauss, they had circulated widely in print and could not be erased.

Within PaJaMa’s network of friends and lovers, a kind of freedom existed in the lack of labels and sexual categories, in the unnamed nature of things.

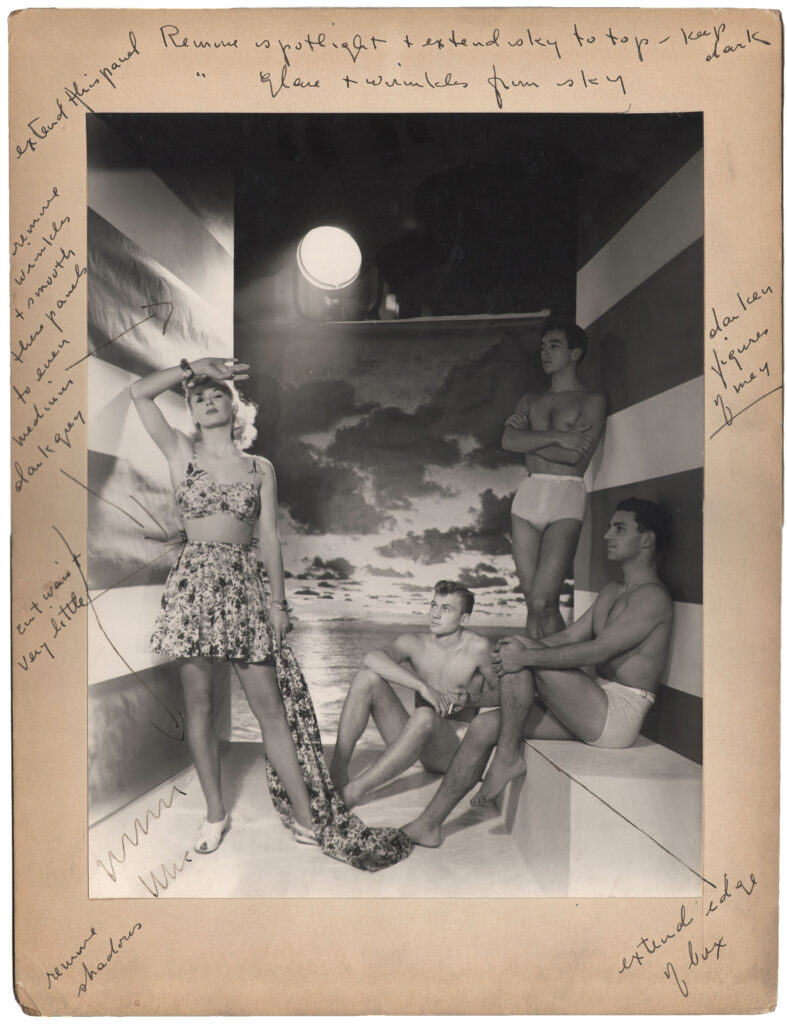

Mauss tracked down objects and models across different genres of Lynes’s artistic output, showing not only their interconnectedness but also how they fed into and fueled one other. In one example, he shows the evolution of a photograph within Lynes’s world. For a swimsuit advertisement shot in 1937, Lynes built a set that looks like a cabana, with a mural-size photograph of a beachscape as backdrop. The image captures a stiff composition of three men staring at a woman in a bathing suit. It has long been suspected that Lynes reused commercial sets after-hours for his erotic work, and Mauss provides evidence in the form of one of Lynes’s better-known photographs titled Demus, also from 1937, in which a dejected-looking nude man cradles his head in the same cabana against the same seascape. Here, Mauss writes, the setting has been transformed to evoke a well-known 1836 painting by Jean-Hippolyte Flandrin, whose figure of another “sad young man” became “an archetypal cipher for the homosexual’s isolation from society.”

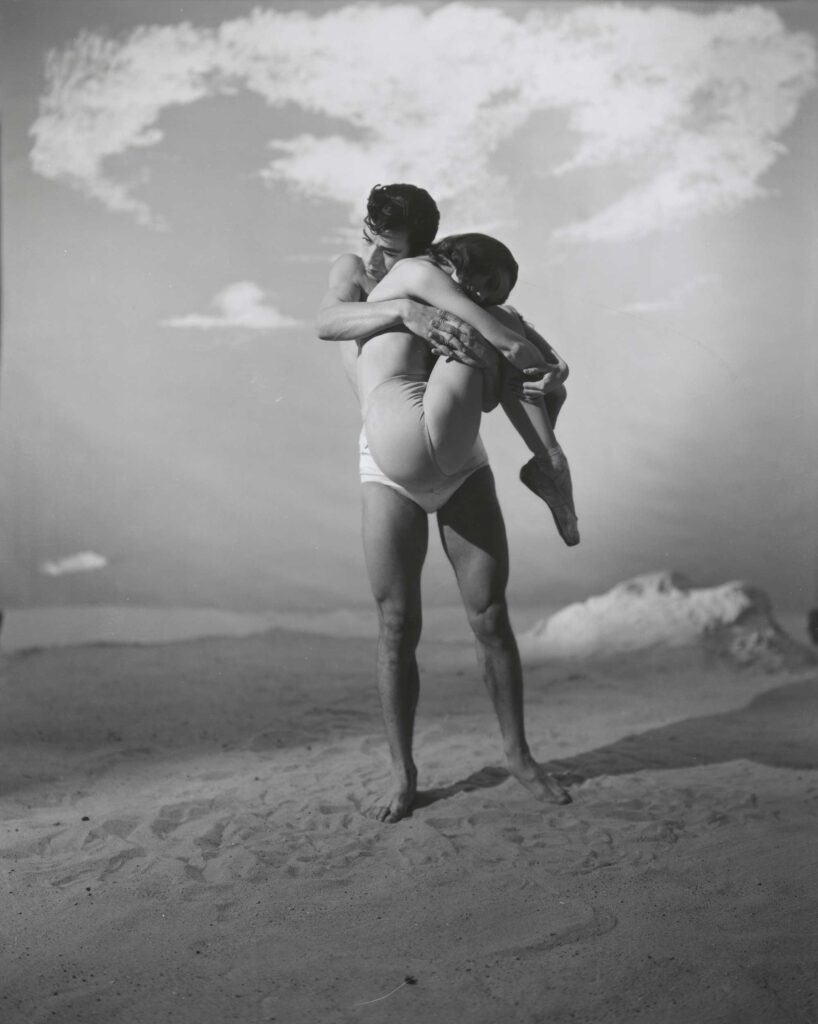

Jerome Robbins Dance Division, New York Public Library © Estate of George Platt Lynes

Courtesy Keith de Lellis Gallery © Estate of George Platt Lynes

Building on this revelation, Mauss identifies one of the male models in the fashion advertisement as the American ballet dancer Nicholas Magallanes, one of Lynes’s frequent subjects and a charter member of the New York City Ballet. A 1950 photograph Lynes made for George Balanchine and Jerome Robbins’s ballet Jones Beach uses a similar otherworldly set of a beach and features Magallanes cradling the dancer Tanaquil Le Clercq, whose pose is strikingly akin to that of the model in Demus. Finally, Mauss links this dance image to a spectacular male nude that Lynes photographed on the same set as the Jones Beach image, perhaps on the same day, in which a male model strikes this same pose but is turned upside down and rotated toward the camera in what Mauss describes as “a flagrant consecration of the rectum.”

Earlier in his text, Mauss asks: “Could Lynes’s work be seen as a new form that fused commercial imaging with vanguard aesthetics, and opened up the performative potential of the photographer’s studio? Would it not be more accurate to call Lynes an artist who used a camera rather than labeling him a studio photographer?” Though photographers may bristle at the second question, it identifies Lynes’s work as an important antecedent to the conceptual photography that prevailed at a much later period in the 1980s. As Miller writes in her essay on PaJaMa, the staging of scenes for the camera “anticipated the postmodern turn toward artists who used photography as an instrument of self-performance and role-playing.” In the staged photographs of PaJaMa, one begins to see a precursor to the far-off stares of motionless figures in Gregory Crewdson’s tableaux or, as Miller notes, artists of the Pictures Generation, including Cindy Sherman.

Princeton University Art Museum

Body Language is part of a resurgence of interest in these mid-twentieth-century queer photographers, beginning in 2019 with two concurrent shows about queer modernism in New York: Lincoln Kirstein’s Modern at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, and The Young and Evil, curated by Jarrett Earnest at David Zwirner Gallery. Since then, the gay photography historian Allen Ellenzweig has published an extensive biography of Lynes, The Daring Eye (2021), and the art director Sam Shahid has released a documentary about Lynes titled Hidden Master: The Legacy of George Platt Lynes (2024). Artists have also depicted similar themes of love and desire, particularly through staged photography. These projects include Ian Lewandowski’s intricate and luminous contact prints of queer communities in conversation with vintage prints by PaJaMa and Lynes and the recent exhibition Communion at Brick Aux Gallery in Brooklyn of photographs by the self-taught photographer Kris Mendoza, who describes sharing a “spiritual connection” with PaJaMa.

The concept of a “gift image”—an artwork that has no immediate purpose other than to act as an expression of friendship or shared queerness—is particularly important to consider now, in a time when art and arts education have become over-professionalized. Mauss considers the function of gift images to be “not unlike love letters, or the circulation of painted portrait miniatures among friends, lovers, and family members in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century England and the United States, or the exchange of painted fans inscribed with verse between nineteenth-century painters, poets, and their muses.” Artists should be trading more inscribed fans; as something to be shared among artists, this book shows the potential of such an exchange. Lynes, the authors of Body Language note, was devoted to creating a “future history of art”—a line that is also used as the book’s epigraph. In a sense a gift image itself, Body Language provides a fascinating, deeply researched background for the enigmatic works these queer artists left behind, helping to illuminate their contributions for generations to come.

Body Language: The Queer Staged Photographs of George Platt Lynes was published by the University of California Press in 2023.