Abelardo Morell: The Universe Next Door

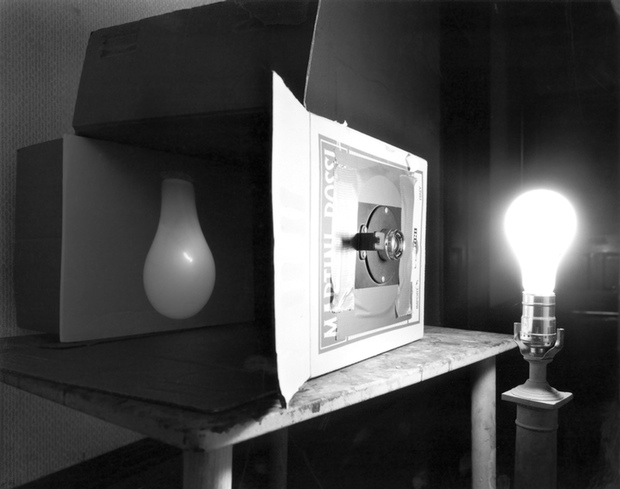

Abelardo Morell, Light Bulb, 1991. All images © Abelardo Morell and courtesy the Art Institute of Chicago.

Photographer Abelardo Morell is a cunning revivalist, or so it would seem from Abelardo Morell: The Universe Next Door. This retrospective at the Art Institute of Chicago juxtaposes work inspired by nineteenth-century cameraless techniques with an impressive assortment of straight photography made over the last twenty-five years. Variety aside, the exhibition is mainly remarkable for the pictures made by camera obscura, the pre-photographic optical principle behind Morell’s most invigorating work since 1991.

On a basic level, the camera obscura operates like the human eye. Light entering a hole in a closed box projects onto the box’s interior an upside-down image of the world. In the case of the eye, the brain realigns the image to conform with reality. Early in his career, Morell built and photographed a camera obscura and the image it projected with a conventional camera placed outside the box. The resulting work, Lightbulb (1991), isolated an important characteristic of his visual vocabulary: an understated surrealism that reconsiders elementary photographic rules by inflecting a single frame with multiple perspectives and affects.

This emphasis on uncanny juxtaposition became more concrete when Morell enlarged the scope of his project and began using natural light. Manipulating a room in his house, this time with the camera inside, Morell shot only the image projected through the pinhole. Camera Obscura: Houses Across the Street in Our Bedroom, Quincy, Massachusetts (1991) required a prolonged exposure of eight hours. In the picture, the lone but massive bed seems to be dreaming. What is it dreaming? Perhaps the image above of several shrunken, dim, and upturned houses. Seminal for Morell, the picture established a symbolic affinity between private or interior space and the camera obscura; for him, both have the power to transform and subdue the outside world. In subsequent years, the camera obscura image invades blank areas, often walls and beds, as if they were screens. Sometimes it even belittles the external world. In Camera Obscura: The Sea in Attic (1994), the projection of the swirling sea becomes a dismal stain on the architectural space, itself self-assured and seductive.

As singular as they are, these camera obscura pictures fit neatly into an overarching view. For Morell, photography is not only a magical realm, as reflected in the exhibition’s title, which borrows from an e.e. cummings poem: “listen;there’s a hell / of a good universe next door;let’s go.” The everyday world is also inherently photographic—that is, ordinary things can unpredictably function as camera lenses. Both of these ideas repeat dogmatically throughout his work. For evidence of his first idea, one might look among his pictures of domesticity that frequently incorporate the silhouette of the classic American house. In Laura and Brady in the Shadow of Our House (1994), Morell’s children loll idly amid scratches in the dirt representing windows, a door, and a picket fence. Here, the shadow-house dignifies the scratched drawing as an architectural elevation, which in turn “house trains” the outdoor space, giving it the intimacy of a real home but the pixie charm of a dollhouse.

Morell’s second idea about lenses embedded everywhere in the world is encapsulated by a different picture made the same year. Shadows During Solar Eclipse (1994) seems fairly ordinary until we learn that the pockmarked silhouettes edged with light and covering the ground are so many pint-sized images of the semicircular sun in eclipse. Hundreds of intervals between the leaves above take up the role of pinholes. Though proving Morell’s argument about the world’s photographic nature, the picture also highlights an unfortunate feature of his work in general. The fascination with optical workings that uniformly infiltrates his oeuvre does not always produce pictures of great visual interest.

In 2005, Morell switched to color film and replaced the pinhole with a diopter lens to shorten exposure time and sharpen focus. A prism located within the camera obscura righted the projection. Upright Camera Obscura: The Piazetta San Marco Looking Southeast in Office (2007) is a later outcome of these modifications, by which the unprecedented clarity of the diopter projection allows the outside world to both dominate and solidify. In Morell’s earlier pictures, the projection of exterior architecture has a spectral quality. Here, it has the robustness of fact. Yet what stands out most is color itself, which saturates every aspect of the image. In Camera Obscura: Garden With Olive Tree Inside Room With Plants, Outside Florence, Italy (2009), color flattens the imaginative difference between the plushness of the natural verdure outside and the greenhouse artifice inside. Thus distracting from Morell’s previous emphasis on the strange encounter between incongruent worlds, color also changes the psychology of his camera obscura format. It goes from eerie fascination, earlier expressed by the tension between grayscale tones, to straightforward pleasure. Put simply, everything now looks equally, ecstatically beautiful.

Abelardo Morell, Tent Camera Image On Ground: View Looking Southeast Toward The Chisos Mountains, Big Bend National Park, Texas, 2010.

In 2010, Morell took the camera obscura outdoors. At Big Bend National Park in Texas, he erected a tent camera fitted with a periscope lens that directed the projected image onto the ground. Whereas nineteenth-century photographers used tent cameras to create precise records of the American West, Morell’s pictures took a pictorially adventurous route. Projecting a colossal elevation at a remove of miles onto the dirt at his feet distorted natural scale. Gravel, stone, and shrub pop out in pictures such as Tent Camera Image on Ground: View Looking Southeast Toward the Chisos Mountains, Big Bend National Park, Texas (2010). They are enlarged protoplasmic blotches among the miniaturized projections of gigantic limestone canyons and mountains. Dust powders the plane as irregular speckles. When Morell staged the tent in the urban outdoors of New York, mildly textured sidewalks or uniformly coarse park ground gave the projections a deliberately stippled appearance. The implied dialogue with late-nineteenth-century pointillism is particularly apparent.

Morell’s photographic wizardry is undoubtedly impressive, particularly in the tent-camera pictures. Yet his tenet of “abiding by the rigor of reality,” which he explains with a Zen saying about going to a tree if you want to write about it, would be admirable if the pictures exceeded the sum of their visual effects. Sadly, the plein-air camera obscura pictures fail to shake this trap; their pictorial highlights are simply equivalent to their optical tricks.

Abelardo Morell: The Universe Next Door is on view at the Art Institute of Chicago through September 2. For more information, click here.