An Outsider in Rio

Kurt Klagsbrunn, Dama acompanhando a corrida no Jockey Clube, Rio de Janeiro, 1945

Kurt Klagsbrunn documented the life of Rio de Janeiro with an outsider’s sense of awe. A Jewish Austrian refugee, he arrived in the city in 1940 and photographed its people and places until 1960, the year the government decamped for Brasília. As noted in the title of this recent exhibition at the Museu de Arte do Rio—Kurt Klagsbrunn, um fotógrafo humanista no Rio (1940–1960)—he was a humanist photographer, and subscribed to no specific viewpoint in his images of celebration and demonstration, hard labor and elite leisure. He used dozens of cameras, some of which were on display here, celebrating the city as often as lambasting it, at times doing both at once. The presentation was part of the FotoRio 2015 program as well as a series at the Museu de Arte do Rio to celebrate the city’s 450th anniversary. Klagsbrunn seems a worthy, lesser-known subject through which to explore the city’s particular midcentury moment: it was a haven to refugees during World War II during its twilight as capital city, not long after which many artists, including Klagsbrunn, were expelled by the dictatorship.

Kurt Klagsbrunn, Engraxate na Cinelândia, ao fundo o Palácio Monroe, Rio de Janeiro, 1940s

Klagsbrunn’s family escaped Nazi-occupied Austria, securing passage through Lisbon to Brazil (the exhibition is organized in part by his niece and nephew). The exhibition begins with early photographs he took in Europe: contemplative, obscured scenes of 1930s Austria, followed by melancholy pictures of Lisbon, of his father at a window or a boat leaving the port, as hands at shore wave scarfs leaving ghostly trails. This darkened and brief prelude makes way for a platform that gives view to a huge curved screen, on which are projected beaches, sloping rock formations, sweeping views of the bay—offering an entrance into Rio much like the photographer’s own. (Unfortunately, some of the projected images appear somewhat stretched.) The wall text, which describes Klagsbrunn’s arrival in the city in 1940, could just as easily have been an exclamation point.

Kurt Klagsbrunn, Pausa para o café, Minas-Gerai, 1947

Klagsbrunn wasted no time: he took no less than 100,000 photographs of his new city. The austerity of his early pictures quickly gives way to crowded street scenes with a focus on character, whether a trolley fish seller, a carnival samba dancer, or a Carioca walking her dog in Copacabana. A chic young journalist eyes the camera suspiciously as a two white-coated waiters dote on her; a grisly greengrocer looks on tiredly from inside his shop. The exhibition includes clippings from the newspaper column in which many of the images originally appeared, “O que o turista nota no Rio” (What the tourist notices in Rio). An opposite wall illustrates how Klagsbrunn’s appreciation extended to the sloping lines of the city’s then recent deco architecture—his few forays into abstraction. His frame is more often frenetically clasped around action: the slope of a boardwalk, fitted so it almost bulges out of the frame, or a simple scene of men taking their coffee, so crammed with detail it appears a shade away from chaos. Paradoxes occur often, as in pictures of the mobilization of forces in World War II: graceful ballet dancers in white are surrounded by a gray mass of soldiers; in a group of dozens of nurses, a woman on the bottom right gives a dubious smirk. The photographer’s own off-kilter sense of humor is never out of sight.

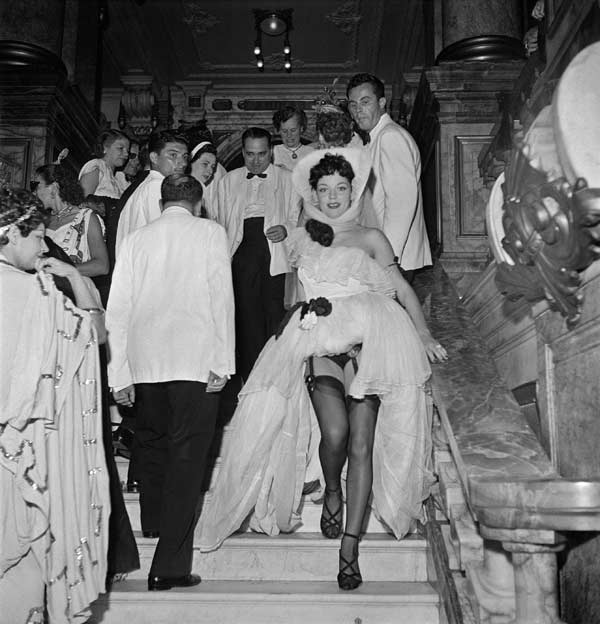

Kurt Klagsbrunn, Baile de carnaaval no Teatro Municipal, Traje permitido fantasia ou à rigor, Rio de Janeiro, 1949

The show honored his outlook, gathering a wealth of material in support of the photographs, including clippings as well as lenses, cameras, and numerous carefully maintained photography books and manuals. Klagsbrunn’s photographs can at times lapse into a postcard-version Rio—most of the work he published appeared as editorial work in glossy magazines. But he had plenty of other, more democratic subjects that he tirelessly pursued: he documented the working class and the black culture of the city in detail, particularly dance subcultures such as capoeira and gafieira. Across from his published photographs of the famous and elite, from Niemeyer to Eva Perón to carnival banquets to jockey clubs, were his images of football games, favela life, and sambistas—which today define the culture of the city.

Kurt Klagsbrunn, Gafieira, Rio de Janeiro, 1948. All images courtesy Museu de Arte do Rio

The exhibition closed with a heavy-handed message about Rio’s rise and fall in the twentieth century: two images hang side by side, one of a 1950s protest in the city center, the other of a tour group from a few years later, at a clinical distance from the space-age severity of Niemeyer’s new capital buildings in Brasília. It’s a point not overtly made until the exhibition’s end—and draws out a guiding principle from Klagsbrunn’s encyclopedic output. Only then do we see Klagsbrunn didn’t just photograph a bygone city, but was perhaps obsessively trying to preserve the one that belonged more to its people than to bureaucracy.

Kurt Klagsbrunn, a humanist photographer in Rio (1940–1960) was presented at the Museu de Arte do Rio from April 14, 2015–January 31, 2016.