Chris Killip’s Photographs Are Hard Evidence of the Human Soul

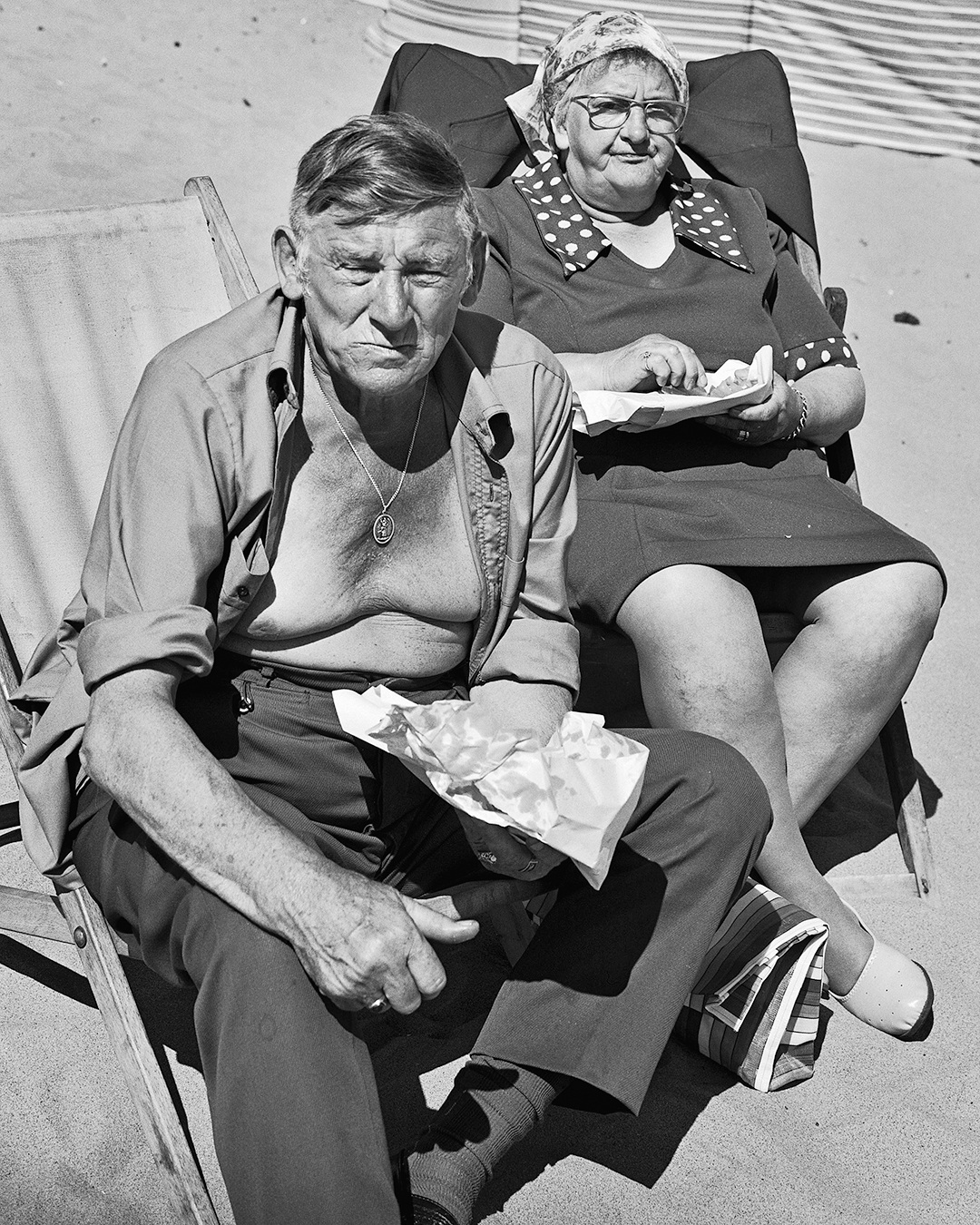

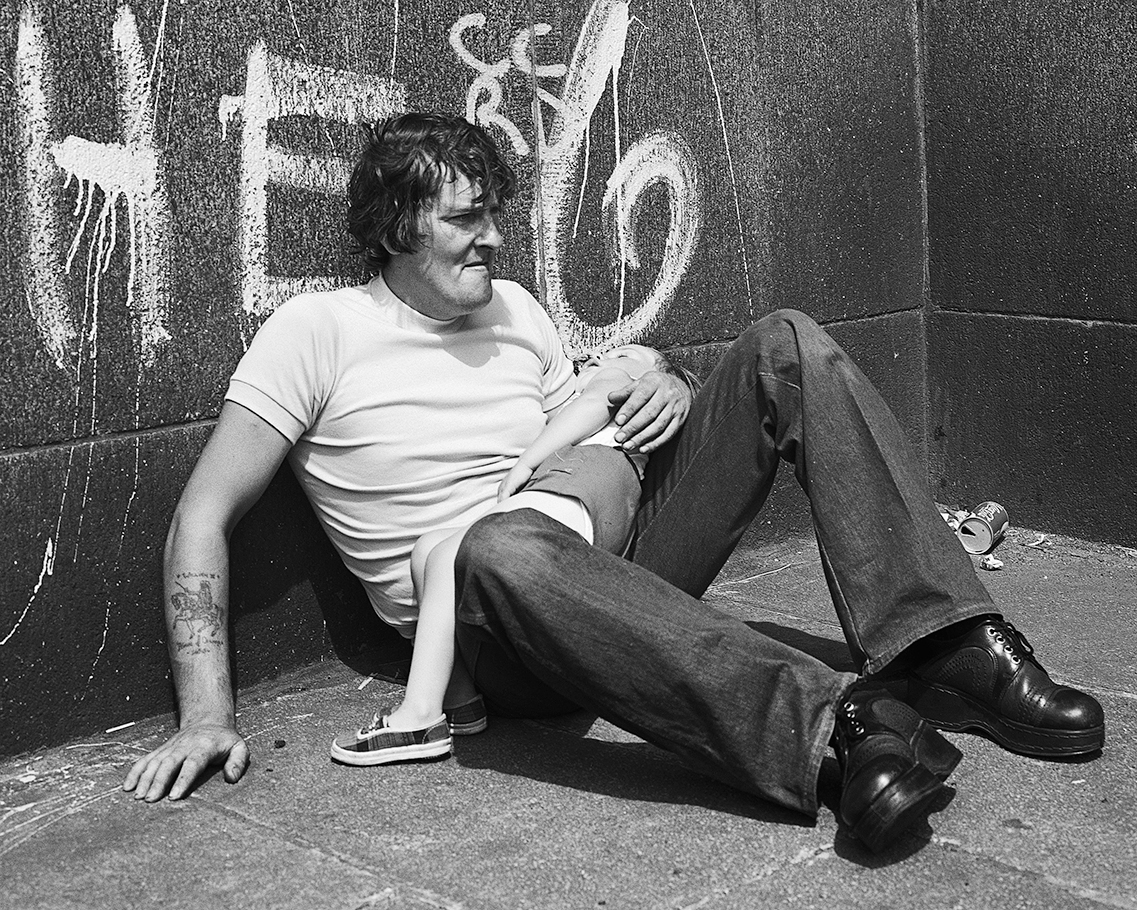

Chris Killip’s photographs—black and white, crisply detailed, at once lush and stark—tend to center on working-class people, hard-pressed citizens on the job and at rest. We see them collecting sea coal, toiling in a tire factory, or withdrawn into attitudes of wariness, disenchantment, exhaustion. The weight of the world is upon them, more often than not, and this pressure, bearing down on vividly particular faces, bodies, and landscapes, can be taken to be Killip’s abiding subject. But the pictures convey considerably more than a bleak historical chronicle or sociological report. Killip imbues his subjects and scenes with a sense of urgency, mystery, and radiance. In his greatest work, he seems to deliver more than a photograph can be expected to communicate or contain: hard evidence of the human soul, flickering like embers in a heap of ashes.

The following interview was excerpted from a conversation conducted in Killip’s home in Cambridge, Massachusetts, an easy stroll from Harvard University, where the photographer has taught since 1991. —Michael Almereyda

Michael Almereyda: When you were approached to mount a retrospective of your work, what flashed into your head?

Killip: Pleasure at the thought. Nobody had ever asked me to do this before. I am fond of and familiar with Ute Eskildsen from the Folkwang Museum, and it was her suggestion. She is a person that I respect greatly. I couldn’t do it with many other people; I don’t trust other people in the way that I trust her.

Almereyda: I know that your original selection of images was very spare, and she helped fill it out.

Killip: Well, it was a process. I’d never gone back to my archive and looked at what I’d done, and Ute made me rethink. My book In Flagrante was published in 1988, and every curator of every exhibition that I’ve been in since has referred back to that book. Ute was the first to say: “What didn’t you publish? What else is there?” It was a great pleasure, but also a great task, which took more than two years, to go through the archive. I also digitized everything while I was doing this, thought about it, printed pictures in different ways.

We included many pictures that I had not considered in years, that I hadn’t published. I thought at the time maybe an image was too nihilistic, or too emphatically strong, or that I might have offended the people in the photograph. There were all sorts of complex reasons why things were never published.

Almereyda: Why don’t we take a specific case?

Killip: There is an image from 1977 called Celebrating The Queen’s Silver Jubilee: I like the picture very much. But I can remember processing and printing it, looking at the contact and thinking: “Oh, my God, I can’t show this.” There’s a very old lady who has been made up for the occasion by her friends: they’ve powdered her face but they’ve been rather overzealous, and the flash has hit her overpowdered face, and, as my cousin would say, “She looks like they dug her up.” I remember thinking at the time: I can’t show anybody this image, it’s just too strange. Now I don’t think that. The picture is such a supercharged Martin Parr-ish image, with the Union Jack in the background and people smiling, and the words The Queen’s Silver Jubilee right there.

Almereyda: Your work often has a political undercurrent—if not an explicit acknowledgment of the political situation.

Killip: Well, it would, wouldn’t it? I mean, I was living in the industrial community of Newcastle, starting in the mid-1970s. I remember the editor of the Saturday magazine of the Sunday Telegraph asking me to photograph the men from the miners’ strike. I didn’t want to do the story for them because it is such a right-wing newspaper. He asked me which side was I on? I was quite shocked by the question. It had never occurred to me that I could be on anything other than the side I was on!

Almereyda: But including political elements in your work is not about picking sides; it’s about openly saying that your work, your worldview, is conditioned by historical forces.

Killip: It was natural. I had no wish to deny it. I was also influenced by John Berger’s TV program Ways of Seeing. I was so excited by that. I was just trying to understand then that no matter what you did, you inevitably had a political position. How declared it was was up to you, but it was going to be inherent in the work, and it was something you should think about as a maker. I never worried about my position in the art world. I thought time and history would ultimately judge me, that my job was to get on with it, to make the work and to make it wholeheartedly from what had informed me.

Almereyda: Was there another photographer who pointed in that direction?

Killip: Maybe the least obvious—and the most obvious—would be Walker Evans. It was Evans’s coolness, about surviving McCarthyism, and all the things that Evans survived; and still you knew he had a distinct political position: it was in the work. Evans gave me great heart about that. He had navigated much more difficult circumstances than I had. In America, he had to live through a much more charged political situation than the liberalism of England. In America, it’s much more of a minefield for people who are not of the Right.

Almereyda: I never thought of him having to negotiate that. He seemed so entrenched when he was working at Fortune magazine. It’s interesting to think that he was actually in a perilous situation.

Killip: Well, the man who made The Crime of Cuba [1934] had to be very careful. Evans never spoke about his politics, because McCarthy was right behind him—and all the evidence against him was there.

I was also keen on Paul Strand, but I moved from Strand to Evans— attracted by Evans’s greater sophistication, not as an image-maker but as a thinker. Strand was a good image-maker, but Evans was a much more interesting man. It’s very ironic that Strand would make something like his Mexican Portfolio [published 1940], which seems patronizing as it’s so much about the beauty of poverty.

Almereyda: How do you see your political awareness coming through in specific images?

Killip: One picture is of a burned-out block of flats in Newcastle. Some people have got their clothes drying on the balcony, and somebody else has got flowers in their window. I think it’s so strange, this optimism. This was a specific moment—1976— in Newcastle history, when some people in public housing were burning themselves out of their homes in order to get rehoused. My interest was in the people who didn’t. But at that time, my pictures were known to Newcastle City Council, whose leader at a council meeting stated (it’s in the minutes of the meeting) that my work was never to be exhibited at any council-controlled museum or gallery in Newcastle, because I was showing the “wrong” image of Newcastle.

Almereyda: You were close with a lot of the people in the pictures you took. That’s been an important ingredient in what you do.

Killip: Yes. I remember speaking with Josef Koudelka in 1975 about why I should stay in Newcastle. Josef said that you could bring in six Magnum photographers, and they could stay and photograph for six weeks—and he felt that inevitably their photographs would have a sort of similarity. As good as they were, their photographs wouldn’t get beyond a certain point. But if you stayed for two years, your pictures would be different, and if you stayed for three years they would be different again. You could get under the skin of a place and do something different, because you were then photographing from the inside. I understood what he was talking about. I stayed in Newcastle for fifteen years. I mean, to get the access to photograph the sea-coal workers took eight years. You do get embroiled in a place.

Almereyda: Let’s talk about some of the other images that you retrieved.

Killip: There is a picture of a man who reminds me so much of my father and my father’s friends. I look at him, and I recognize him as a working-class man with a trade. How can I know this? I know it instinctively. Something about his attitude and his look and his unabashed stare: he is looking directly at me and questioning me. My father has also served an apprenticeship in his trade as a fitter before he had a pub. Both are men of pride. I didn’t publish this picture when I took it, because I didn’t think this was so important. Now I think differently.

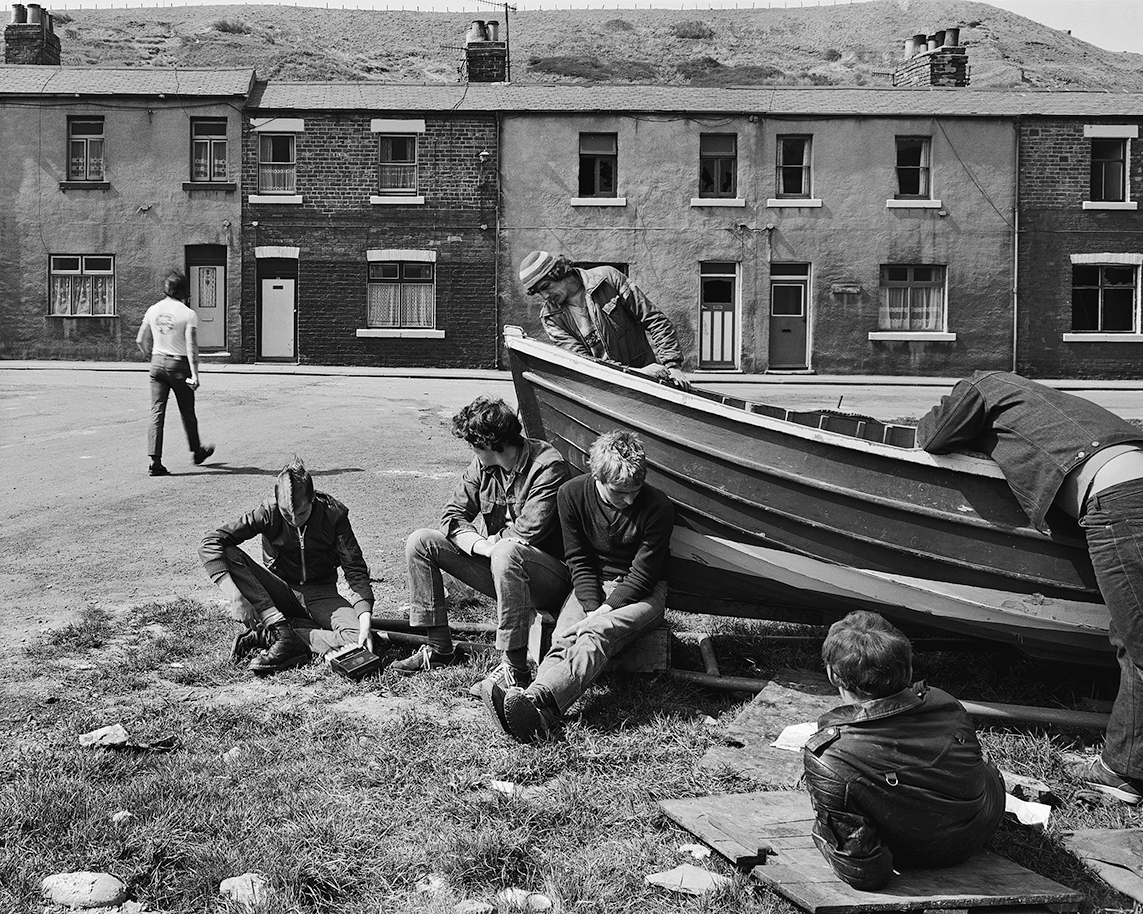

Another picture features graffiti on a wall that says “Bobby Sands, Greedy Irish Pig,” and next to it is a graffiti that says “Smash the IRA” [Housing Estate on May 5th]. I never released this picture while I was living in Newcastle. I felt it was too much about prejudice and intransigence. It’s from May 5, 1981. I can tell you the date, because it’s when Margaret Thatcher announced on the radio program The World at One that the IRA hunger-striker Bobby Sands was dead. I was in the darkroom, printing a picture. She said it so triumphantly that I stopped what I was doing, got my 5-by-4, got in my car, and went to the only place I knew that Bobby Sands was memorialized in any way. It was in a public housing project in North Shields, which is fiercely Protestant, and I photographed the graffiti in its context. Kids came up and asked could they be in the picture, and I said Sure. I take a while to get anything together, so they got a bit bored and they’re messing around, but the picture also shows the circumstance of the estate. You can see where people are burning themselves out. Six years after the other pictures I took, where people are burning themselves out of their homes, it’s still going on. You can see somebody’s washing on the line. It’s significant that nothing has changed in the six years.

For me, it was a very sad picture. North Shields is very linked to shipbuilding, and in Britain shipbuilding is dominated by the “Orange Order,” which means that no Catholic can work in shipbuilding. Something about working-class bigotry is so strong for me in this picture. In another way, it’s about how history is lived by working-class people, and how bigotry is passed down, restraining and constraining lives.

Almereyda: The children seem kind of innocent of it.

Killip: They could be innocent of it, but they’re not unaffected by it. Your innocence can’t last. Bigotry is powerful.

These pictures belong to a time that’s gone. When I looked at my work on the walls of the museum in Germany, I realized that I was, by default, the chronicler of the “De-Industrial Revolution” in Britain. I knew this, but I didn’t ever know it was blatant until I saw it on the wall in this retrospective, so contextualized. For me, it was overwhelming to think about what had happened to the two countries and how different they now are, Germany full of manufacturing industry, Britain with none. There seems to be no way around it: here the past is another country.

This article was originally published in Aperture issue 208, Fall 2012, available for purchase or in the Aperture Digital Archive.

All photographs © the artist.