The PhotoBook Review 016: Editor's Note

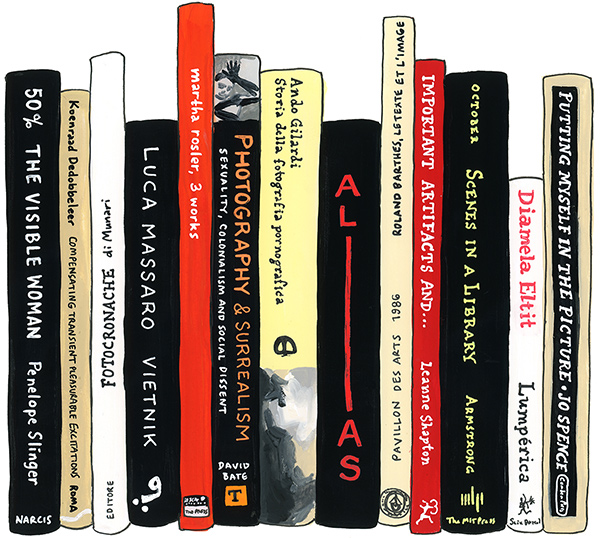

Jane Mount, Ideal Bookshelf 1112: Federica Chiocchetti, 2019

Courtesy the artist

In the first issue of The PhotoBook Review (2011), Jeffrey Ladd closed his Editor’s Note by raising a glass to an obsession: the photobook. I confess to having a further obsession, within that obsession: “photo-text” books, where images and texts are equally prominent.

As a labyrinthine flaneuse, I never seek truth but my Ariadne. What follows is a fragmentary attempt to reconstruct my “clinical record,” understand the thread that drew me toward photo-text intersections, and explain why I find them so alluringly addictive. In doing so I will connect my trajectory to the content of this issue and the titles from my ideal bookshelf. Ideal, indeed . . . Richard Burton said that “home is where the books are.” Alas, I have given up on understanding where I live; I might never see these spines together on the same shelf, so a massive thank-you to Lesley A. Martin, Jane Mount, Samantha Marlow, and the Aperture team for making me feel at home within these pages.

Anamnesis:

Please allow me to indulge in the hashtags, as in these schizo-verbo-visual-bombarding times, I find them a useful typographic tool to keep our fragile attention alive.

#literature Italo Calvino’s words in his 1955 “The Adventure of a Photographer,” as well as Julio Cortázar’s 1959 short story “Las babas del diablo,” triggered my fascination with photography more than any image did (apologies to all the image makers in the audience).

#photographytheory Even more pathologically, the philosophical discourse around photography shaped my research interests in a sort of “death-of-the-author mode” toward what Joan Fontcuberta described as “the virus of fiction.” I developed a curiosity for eccentric, somewhat surreal imagery that interrupts, departs from, or plays with our perception of what we tend to call reality.

#complit The fascinating field of comparative literature infected me with further masochistic research methodology: why simplify your life by focusing on one discipline, epoch, geographical area, or even one author, when you can have a complex and diverse blast by mingling multiple arts and authors from different linguistic regions and periods? I am indebted to Professor David Bate, whose seminal 2003 book Photography and Surrealism (discovered through David Evans’s terrific Critical Dictionary [2011]), among his others, taught me how to unpack an image through words and encouraged me to not give up on the difficulties of genre studies within photography. The only novel on my ideal bookshelf is Diamela Eltit’s Lumpérica (1983), an uncanny, claustrophobic, and almost plotless text, impossible to categorize.

#Brecht&Benjamin Although we might remember them as chess rivals, from the famous 1930s Svendborg photographs, Bertolt Brecht and Walter Benjamin shared very similar views on photography. “What we must demand from the photographer is the ability to put such a caption beneath his picture as will rescue it from the ravages of modishness and confer upon it a revolutionary use value,” explains Benjamin in “The Author as Producer” (1934). While writing an essay on Brecht’s Kriegsfibel (War primer; Eulenspiegel Verlag, 1955) for my modern literary theory course, I stumbled upon the above sentence. I would only realize a couple of years later the almost shamanic impact it had on the development of the Photocaptionist.

#degenerateart In one random online search I came across a quirky workshop organized by the then emerging platform Self Publish, Be Happy in London. It was called “Degenerate Art,” and its aim was to respond to the eponymous exhibition organized by the Nazi Party in Munich in 1937. The teacher was no less than Adam Broomberg. He made us create a collaborative photo-text zine where the obnoxious words of the exhibition’s catalogue and imagery from an anonymous archive of vernacular Nazi Germany prints, a blind buy on eBay, mingled in a quite disturbing way.

#identitycamouflage I never stopped following the incredibly prolific duo Broomberg and Chanarin, and I have included on my bookshelf their marvelous book ALIAS: None of the Artists Exist, which is also the catalogue of their 2011 edition of Kraków Photomonth. It is inspired by my favorite writers (Pessoa, Borges, and Bolaño) and it explores another fetish of mine: pseudonyms, heteronyms, and alter egos. Similarly, the artist book Compensating Transient Pleasurable Excitations by Koenraad Dedobbeleer (Roma Publications, 2014) is a catalogue of an imaginary exhibition that irresistibly evokes something that never took place. Luca Massaro’s brand-new self-published Vietnik is a clever visual bildungsroman where, lurking behind his semiotic images, made by his alter ego, we find layers of the young artist’s influences, such as Bob Dylan, Luigi Ghirri, Robert Frank, and Frank Ocean.

#scriptovisualvertigo It is hard to define exactly how my encounter with the artistic and theoretical practice of Victor Burgin has shaped my interest in photo-text intersections, but undoubtedly it has. To honor his contribution to the field, an interview about his forthcoming books was fundamental for this issue. Another important book is Martha Rosler’s 3 works (Press of the Nova Scotia College of Art & Design, 1981), which contains her experimental photo-text piece The Bowery in two inadequate descriptive systems (1974–75), a deadpan critique of the poverty of representation in political documentary. David Campany recently recommended me a great book: the catalogue of a 1986 Parisian exhibition, Roland Barthes: le texte et l’image, that celebrated the author’s writings about art and visual culture by displaying them juxtaposed to the original artworks, from Arcimboldo to Wilhelm von Gloeden. And how could I not include Bruno Munari’s 1944 groundbreaking, witty journey into Photo-Reportage (Domus Publishing Group).

#photocaptionist I was sinking in heavy photo theory at the British Library in the first year of my PhD, when one night I had a strange dream of a grumpy old bloke whose job title was “Photocaptionist.” His occupation consisted of composing creative short texts in response to the photographs he would receive from artists, institutions, and random individuals. I thought that creating an editorial and curatorial platform to explore photo text intersections could be a more playful way to deal with my research. One day I will ask my analyst to interpret that dream.

#thirdsomething When my eyes land on a book spread where images and words interplay, even before thinking about whether they do so successfully or not, I get truly excited by the opportunity for a more enriching viewing and reading experience. As I look at the images, I miss reading the words, so I go back to them and I start missing the images again. In this constant ping-pong, or tension, a third unattainable object, which Sergei Eisenstein called, in relation to montage in film, literature, and art, a “third something,” develops. And it’s only in my mind. Aren’t we often attracted by the presence of an absence? Photo-text pairings are a springboard to dive into our own imaginary world of afterimages and afterwords.

#phemerson I had the pleasure of curating an exhibition of Peter Henry Emerson’s photogravures and pictorial books with a focus on his writings during my fellowship at the V&A, where, brilliantly enough, the Photographs section is part of the Word and Image Department. This opportunity, together with the study of Carol Armstrong’s book Scenes in a Library (MIT Press, 1998), introduced me to the wondrous world of nineteenth century photo-text books. Delphine Bedel showed me one of the first essays ever written on photobooks by Elizabeth McCausland, “Photographic Books” (1942). It was a nice surprise to read that McCausland considered Emerson’s Life and Landscape on the Norfolk Broads (S. Low, Marston, Searle, and Rivington, 1886) “an organic relation between text and pictures,” which for her was “the basic characteristic of the photographic book.”

#imagetextithaca Another game changer was to find out that I was not alone in my obsession: Nicholas Muellner and Catherine Taylor crafted an entire MFA program around image-text intersections at Ithaca College. I treasure the memories of participating in their symposium in 2015, where I met phototext wizard Jason Fulford, whose commissioned collaboration with the fantastic Elisabeth Tonnard is presented in this issue’s centerfold. Muellner and Taylor also recently launched the publishing house ITI Press, and I am grateful to 10×10 Photobooks cofounder Olga Yatskevich for interviewing them. No end to the surprises in the photo-text world. In 1987 an international association called Word and Image Studies was founded with a dedicated journal and series of conferences to “foster the study of Word and Image relations in a general cultural context, and especially in the arts in the broadest sense.” Maybe I can go there for rehab.

#femininemasculine Photo-texts are particularly useful for deconstructing ideology in our society. Gender dynamics and bourgeois heteronormativity are another deep preoccupation of mine. Four books on my ideal bookshelf relate to this theme. I hope an English language publisher will decide to translate Ando Gilardi’s Storia della fotografia pornografica (History of pornographic photography; Bruno Mondadori, 2002), as it’s a rare and amusing study of the origins of pornography that enables us to better understand how it has organized power dynamics differently over time as compared to today. Penny Slinger’s 1971 book 50% the Visible Woman (Narcis Publishing), with its psychoanalytic confrontational photocollages and tissue overlays, is an unsettlingly amazing book that introduces a different language for the feminine psyche to express itself. (Thank you to Susan Lipper for showing it to me.) Jo Spence doesn’t need any introduction. Her brutally honest, tragicomic, autobiographical photo-texts paved the way for the disruption of sexual stereotypes and photo-therapy. Leanne Shapton’s Important Artifacts And . . . (Sarah Crichton Books and Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2009) is the perfect post-breakup photo-text antidote.

#photopoetry A specifific category within photo-text books, in which the challenges of making a successful object are even higher, given poetry’s idiosyncratic DNA. I would like to thank David Solo for inviting me to collaborate on activating his photo-poetry books collection, for his contribution to the Annotated Bibliography, and for his continued constructive criticism.

Time to find a cure for my photo-text addiction.

Treatment:

Be contagious; spread the “virus.” After all, what’s the point of having an obsession if you cannot share it with other people? Discussing photo-text books at the legendary bookshop Shakespeare and Company during last year’s Paris Photo, within Too Many Pictures’ Photobook Week, was a real learning experience in terms of considering new audiences for the photobook. I believe that promoting the concubinage of words and photographs in book form is one of the possible remedies that will help the photobook cross its own bubble border and encroach on the wider soil of a literary audience.

Read more from The PhotoBook Review Issue 016 or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.