The Book of Film

How do filmmakers such as Jean-Luc Godard and Sofia Coppola translate moving images to the printed page?

We have all heard photographs described as poetic, sculptural, painterly, literary, or cinematic. It is commonplace to look outside the medium when trying to account for it. But it will only get us so far. If a photo- graph is described as “painterly,” what might that mean? Caravaggio, Constable, or Kandinsky? If it is “cinematic,” does that suggest Kurosawa, Kubrick, or Cronenberg? Raised on a diet of Alfred Hitchcock and David Lynch movies, you might reasonably feel a Gregory Crewdson photograph was “cinematic.” If that diet was movies by Claire Denis and Béla Tarr . . . maybe not.

Beyond the single image, we often reach for filmic comparisons when discussing photo editing and publications. Of his book New York (1956), William Klein once declared: “Only the sequencing counts . . . like in a movie.” Given its flowing layout and informal framing, we can see what he meant. But it’s also nonsensical—how can only the sequencing count? On page or screen, there can be no sequencing without the images themselves. The late Allan Sekula thought of his photo-text works as “disassembled movies,” but he didn’t say which movies, and some of the directors he admired—Jean-Luc Godard and Jean Rouch—described their own movies as “disassembled.” Cinema’s aesthetics and modes of production are no more unified than those of photography. All the arts can be anything—and they can be like anything.

Such happy confusion aside, there is a particular kind of photographic book we can legitimately call cinematic, and that’s a book derived directly from cinema. Film became a form of mass entertainment alongside the emergence of the popular illustrated press. By the 1920s, all kinds of books related to movies were appearing, both mainstream and avant-garde. Across the ensuing decades, “cinema on the page” became a familiar part of visual culture.

The most popular publications presented movies much like cartoon strips of images and text. Sometimes the photos were frames of the movie itself; sometimes they were shot as stills, by specialist photographers on set. Peaking in the 1940s and ’50s, these cheaply printed magazines and little books were perfect for viewers hungry for a physical souvenir of the movie theater’s projection of pure light. Holding something cinematic in your hands was exciting. In Italy especially, these fotoromanzi of the latest releases were consumed in vast numbers.

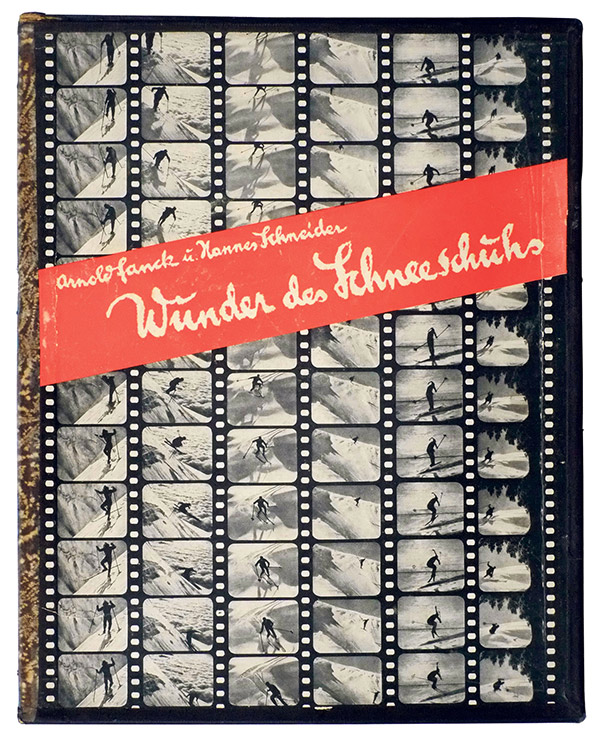

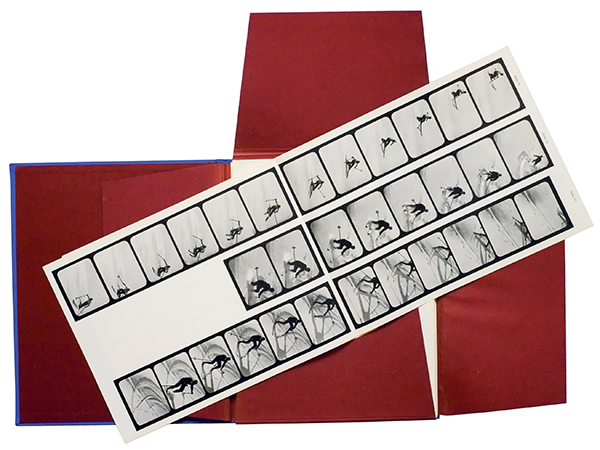

There were also more graphically adventurous experiments. Printed movie frames featured in many interwar avant-garde publications, notably László Moholy-Nagy’s landmark Malerei, Photographie, Film (Painting, Photography, Film, 1925). Moholy-Nagy took inspiration from a remarkable project about skiing, of all things: in 1920, the photographer and filmmaker Arnold Fanck had made an instructional film and was experimenting with printing frames from it. Fanck became fascinated with the dilemma of whether action was better expressed by a single, well-timed photograph or a sequence from a movie camera. The two-volume Das Wunder des Schneeschuhs (The miracle of the snowshoe, 1925) presents copious examples of both, with filmstrips printed on spectacular, unbound foldouts. Studying this book in your lap may not be the best preparation for launching yourself down an alp, but it’s a fascinating presentation of a visual problem.

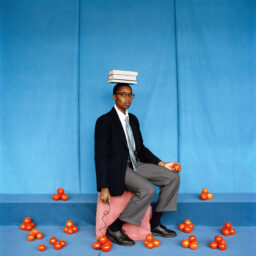

Indeed, the challenge of how to present the time of moving images on the page has never gone away. It is bound to fail, but there are endless ways of failing which can still be instructive, and attractive. The video artist Martin Arnold works with found footage from classic movies. He’s interested in cutting, combining, and repeating shots, often toggling back and forth so the image appears to flutter on the edge of perception. The effect cannot work in print, and yet his 2002 book Deanimated, designed by Anna Bertermann, is remarkable. The pages have a timeline marked out in dots. Along this line, the shots from his films are reproduced in sequence. The longer the shot is held on the screen, the more dots it must span, and thus the larger it appears on the page. In this way, image dimension corresponds directly to image duration. Clever.

In general, most movie-related publications have not attempted that kind of equivalence. The elegant book of Le sang d’un poète (The Blood of a Poet, 1930), Jean Cocteau’s first film, is an elegant example, with elliptical moments from the script punctuated by striking photos shot on set by Sacha Masour. With its antireligious sub- text, the film caused a scandal upon release, but it gained a reputation as one of the key Surrealist films. Published much later, in 1948, the book is a recognition of this. It doesn’t attempt to recreate the film; the relation between page and screen here is complementary rather than supplementary.

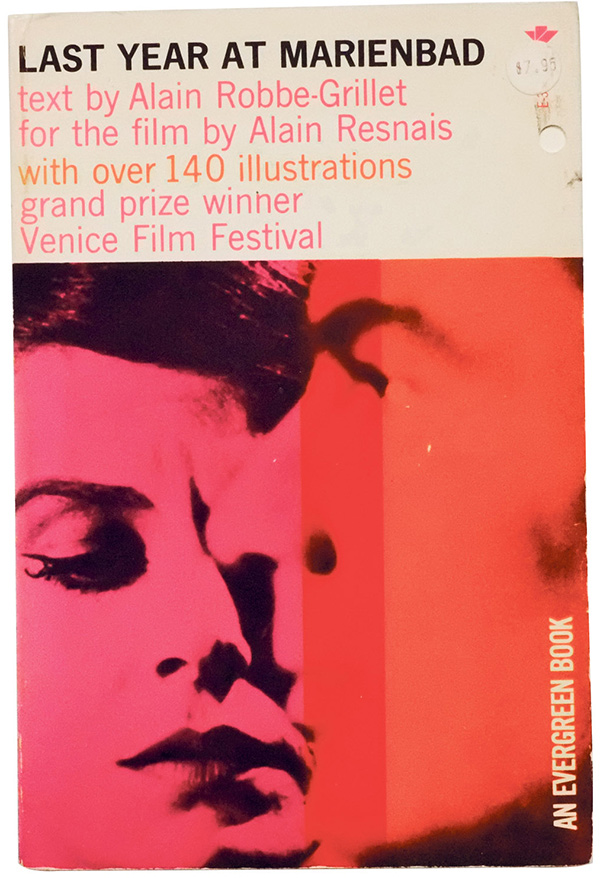

With the rise of television in the 1960s, such books began to die away. Then VHS made films “possessable,” and DVD supplied the supplements beloved of fans and scholars. But as the cinematic book waned, European filmmakers began to make books as a means of revisiting and expanding their movies. Alain Robbe-Grillet converted his scripts written for films directed by Alain Resnais—including L’Année dernière à Marienbad (Last Year at Marienbad, 1961)—into what he called “ciné-novels,” halfway between illustrated script and novelization. Although radically hybrid, the ciné-novel has qualities all its own. Here is Robbe-Grillet explaining in the foreword to his self-directed L’Immortelle (The Immortal One, 1971):

“[A] detailed analysis of an audio-visual whole that is too complex and too rapid to be studied very easily during the actual projection. But the ciné-novel can also be read, by someone who has not seen the film, in the same way as a musical score; what is then communicated is a wholly mental experience, whereas the work itself [the film] is intended to be a primarily sensual experience, and this aspect of it can never really be replaced.”

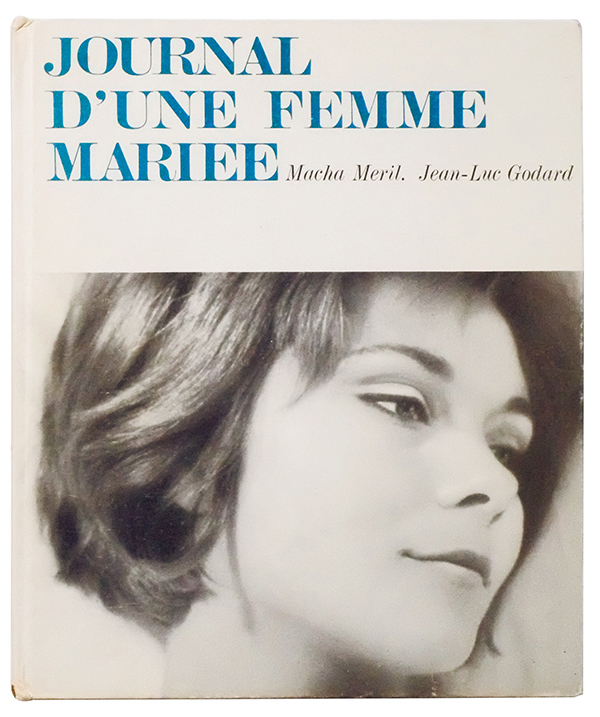

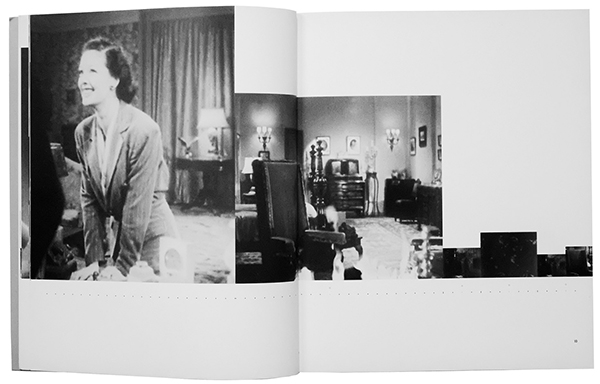

The translation of a film into illustrated text opens up an interpretive gap; cinema’s fixed duration is converted into the more flexible time of reading. On the page, text and image can be contemplated at will and, in the process, the film can be “laid bare” for analysis. In 1965, Godard suggested that “one could imagine the critique of a film as the text and its dialogue, with photos and a few words of commentary.” Godard published print versions of nearly all his films of the 1960s. The book based on Une femme mariée (A Married Woman, 1964) recreates the episodic, first-person structure of the film. Whereas the film showed the married woman confronted with representations of consumer femininity (on billboards, magazines, and movie posters), the book appropriates various styles of layout from popular culture.

In the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s, the decades of European “auteur cinema,” dozens of illustrated books appeared for films by the great directors—Antonioni, Pasolini, De Sica, Tati, Truffaut, Bresson, Rohmer, Fassbinder, Bergman, Buñuel. I should confess here: this is where my affection for photography began. The film stills in these old books were the first images that really impressed me. Cinema seemed to be the means of making the sorts of photographs I wanted to look at. Years later, I was thrilled to come across a video of a 1974 lecture in which Walker Evans described Robert Altman’s McCabe and Mrs. Miller (1971) as “a marvelous bunch of photography.” He was right. Vilmos Zsigmond’s impressionistic camerawork on that film was a kind of photography not seen before, or since. For many years, I knew it only though images in books.

It is important to note that cinematography was included in many of the early books on the history of photography. Then, as film history began to establish itself, the two were split. For example, the first edition of Beaumont Newhall’s Photography: A Short Critical History (1937) included a chapter titled “Moving Pictures,” and even featured Eadweard Muybridge’s sequential locomotion studies on its dust jacket. That chapter was dropped from later editions.

If our histories of photography were to include the innovations of cinematography, the whole map of the medium would need to be rewritten. The exploration of light, composition, visual rhetoric, and communication has always been far more advanced in cinema than in still photography, especially when it comes to color. You only have to look at Jack Cardiff’s Technicolor cinematography for the films of Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger to see this: A Matter of Life and Death (1946), Black Narcissus (1947), The Red Shoes (1948)—nothing in the still photography of the 1940s came close. In working with light projected through a subtle positive-transparency film, color cinema made enormous leaps, aesthetically and technically. Meanwhile, color still photography was held back severely by the practical problems of color print reproduction, which was not very good until well into the 1980s. If you want to see the very best color imagery that was possible between the late 1930s and the late 1980s, look to cinema. But the printed publications dedicated to those color movies are awful!

Surprisingly few cinematographers have made visual books about their work. Man with a Movie Camera (1984) is Néstor Almendros’s illustrated account of how he shot some of the most beautiful films of the 1960s and ’70s. (He won an Academy Award for Terrence Malick’s Days of Heaven from 1978.) Christopher Doyle, renowned for his work with director Wong Kar-wai, has published books of his collages and photos taken on set. A Cloud in Trousers (1998) is his remarkably honest and sidelong account of how he understands images.

The “book of the film” remains split between tedious Hollywood blockbuster franchise cash-ins and more experimental publications for art-house movies. Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Wim Wenders, David Lynch, Larry Clark, Wes Anderson, Mike Mills, and Sofia Coppola have issued innovative books related to their films (little coincidence that all these directors have had a deep love of still photography). The sumptuous photographs taken by Roger Fritz on the set of Fassbinder’s highly theatrical Querelle (1982) predate by a few years the seedy glamour of Nan Goldin’s The Ballad of Sexual Dependency (1986). The book of Wenders’s Paris, Texas (1984) tells the road movie in double-spread frames. In this form, it is easy to see just how much he and cinematographer Robby Müller had learned from the imagery of photographers Walker Evans, William Eggleston, and Stephen Shore.

Two years later, some of Eggleston’s photos appeared in the book of the musician David Byrne’s only feature film, True Stories (1986). Along with Eggleston’s photography, there are images by Len Jenshel, Mark Lipson, and Byrne himself. At once script book, scrapbook, and photobook, it’s a thoroughly idiosyncratic publication, entirely in keeping with the film. (The True Stories revival starts here!)

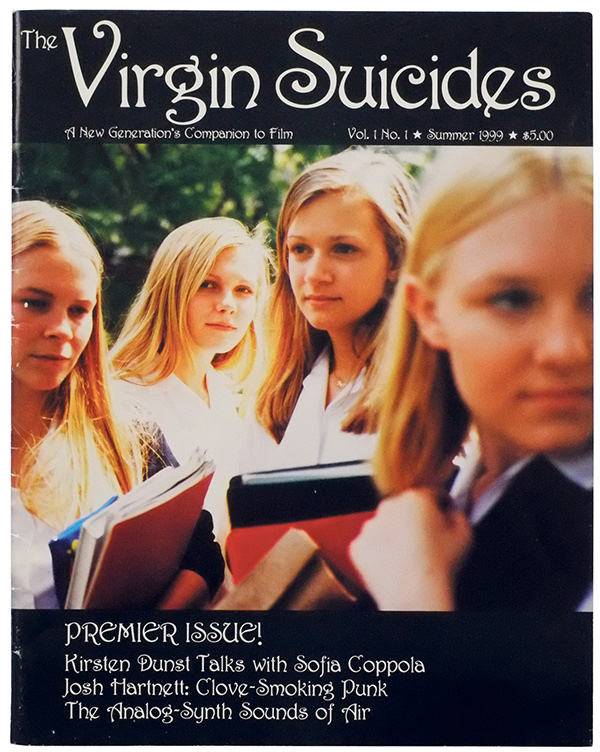

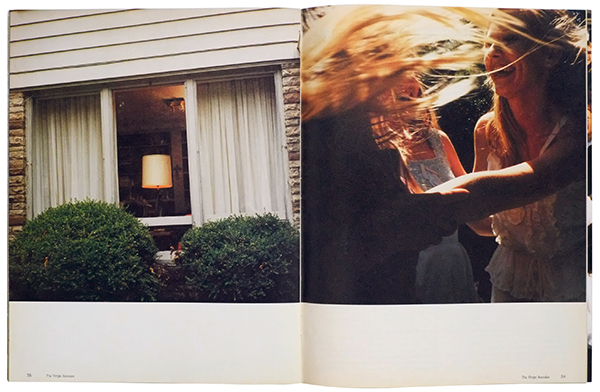

Eggleston’s photography has influenced many filmmakers of the last twenty years, but none more so than Sofia Coppola. All her films are accompanied by publications. One of the most engaging is the fake teen zine of The Virgin Suicides (1999), with Eggleston-esque photos by the late Corinne Day.

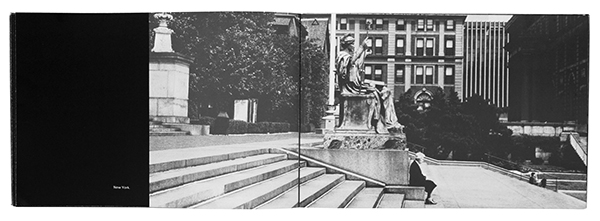

I have barely scratched the surface here. Cinema has given rise to such a great range of photographic books. I finish with my favorite, Alain Resnais’s Repérages (1974). It is a collection of photographs shot over many years in New York, Paris, Lyon, Hiroshima, and London while looking for locations for his films. The majority are for projects he never completed. The format is wide and the full-bleed images with black pages help to suggest a screen in a darkened room. The photographs are documents: raw, grainy, and factual. They are also richly evocative promises that the late director never managed to keep—love letters to the future of cinema. Perhaps someday someone else will pick up this book and make those movies.