Editor's Note

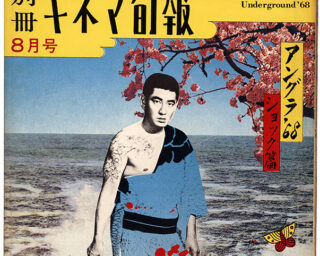

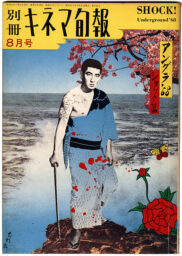

The selection of books illustrated in my photobook “portrait” are the contents of the actual pile of books that are currently on my writing table, some that I am looking forward to reading for the first time, others that it feels timely for me to re-read. I am conscious that there is not a single photobook in the picture-book sense of the word. This reflects my aims for this issue of The PhotoBook Review: to be pluralistic in its approach to the photobook and not merely to propose a checklist for a collectible canon of this essential form of photography.

Since I was a schoolgirl, I have stacked and invariably carried with me a few books most of the time. Like cumbersome talismans, I only need to glance

at their spines to feel their inspiration and anticipate their influence upon my own thinking. Perhaps the most resonant book, when considering the task of guest-editing this issue of The PhotoBook Review, is the modestly sized Writing Machines. (The spine was too thin to include in my photobook “portrait”!) Written by the intellectual goddess of compara

tive media studies, Katherine Hayles, I first read

this MIT Press publication about a year ago. Like

all the text and photobooks that I treasure, Writing Machines seemed to come into my life at exactly the moment I was ready to receive its observations and be inspired by its creativity. I read Hayles’s book just as I was beginning to formulate my ideas for my next long-form text book. I was already aware that perhaps the biggest challenge to writing a textbook about contemporary photographic practices, which range from material objects like photobooks to mobile tools for social action, is that none of us, including me, are fully formed experts in the meaning and significance of this deeply mercurial and shifting terrain. Hayles addresses this challenge in her book (whose subject is post-Internet literature) by writing in three different and distinct ways. She writes in her impressively generous and straightforward academic way about the scope of militating and mitigating factors that now shape creative writing. In a series of “case studies,” she makes connoisseurial judgements on what will come to be seen as the key works in the canon of cyber- and hyper-text literature. Her third writing “voice” is of a fictional character (who bears a striking resemblance to Hayles) recounting the moments and exchanges in her working life when her understanding of literature was reshaped. Hayles points out that we have reached, perhaps for the first time and in response to our digital epoch, a point where intellectual analysis and personal experience need to be intertwined. The inspiration that I have taken from Katherine Hayles’s writing is to be assured that a meaningful assessment of contemporary creative culture that includes photobooks is a blend of personal experience, open conversation, and a commitment to properly analyze what you see as exemplary in a fast-evolving field of creative practice.

Since I was a schoolgirl, I have stacked and invariably carried with me a few books most of the time. Like cumbersome talismans, I only need to glance

at their spines to feel their inspiration and anticipate their influence upon my own thinking. Perhaps the most resonant book, when considering the task of guest-editing this issue of The PhotoBook Review, is the modestly sized Writing Machines. (The spine was too thin to include in my photobook “portrait”!) Written by the intellectual goddess of compara

tive media studies, Katherine Hayles, I first read

this MIT Press publication about a year ago. Like

all the text and photobooks that I treasure, Writing Machines seemed to come into my life at exactly the moment I was ready to receive its observations and be inspired by its creativity. I read Hayles’s book just as I was beginning to formulate my ideas for my next long-form text book. I was already aware that perhaps the biggest challenge to writing a textbook about contemporary photographic practices, which range from material objects like photobooks to mobile tools for social action, is that none of us, including me, are fully formed experts in the meaning and significance of this deeply mercurial and shifting terrain. Hayles addresses this challenge in her book (whose subject is post-Internet literature) by writing in three different and distinct ways. She writes in her impressively generous and straightforward academic way about the scope of militating and mitigating factors that now shape creative writing. In a series of “case studies,” she makes connoisseurial judgements on what will come to be seen as the key works in the canon of cyber- and hyper-text literature. Her third writing “voice” is of a fictional character (who bears a striking resemblance to Hayles) recounting the moments and exchanges in her working life when her understanding of literature was reshaped. Hayles points out that we have reached, perhaps for the first time and in response to our digital epoch, a point where intellectual analysis and personal experience need to be intertwined. The inspiration that I have taken from Katherine Hayles’s writing is to be assured that a meaningful assessment of contemporary creative culture that includes photobooks is a blend of personal experience, open conversation, and a commitment to properly analyze what you see as exemplary in a fast-evolving field of creative practice.

Everyone who has contributed to this issue of The PhotoBook Review is someone that I have learned from and whose opinions on photographic and digital culture inform my own. I am incredibly grateful to them all for publicly performing for this publication the conversational and collaborative relationships that we have. The four conversations that took place between pairs of long-time friends and collaborators offer unique takes on the factors that influence the values and practices of contemporary photography publishing. It has been a privilege to listen in to their recorded conversations and my edits for this issue—and also the Aperture website—focus on the concepts they discussed that resonated most strongly with me. I can already feel the influence in my own thinking of Jason Fulford and David Reinfurt’s conversation in San Francisco in January about the act of paying attention and the possible duration of the present moment. Jason Evans and Keiran Hebden’s thoughtfulness about each digital and analog gesture in their image-making and musical practices shows me just how important it is for us to register the nuanced hybridity of this creative era. Penny Martin and Emily King’s conversation in London reminds me that the distinction between independent magazine and book publishing is increasingly blurred, while perhaps remaining philosophically different on the levels of cultural value and reading experience. Richard Misrach’s interview in San Francisco late last year with Jeffrey Fraenkel about his approach to photobook publishing is delightful evidence that this is a creative field where some of the most innovative gestures can be the most enduring.

I asked four people—Bruno Ceschel, founder of Self Publish Be Happy in London; Mary Fagot, a creative director working in film, interactive media, and print in Los Angeles; Nicole Katz, cofounder of Paper Chase Press in Los Angeles; and Aron Morel, founder of Morel Books in London—to select books for the review section. Each has fine taste in photobooks and unique creative knowledge that I rely on to better understand the whole range of endeavors that constitute the subject of photobooks.

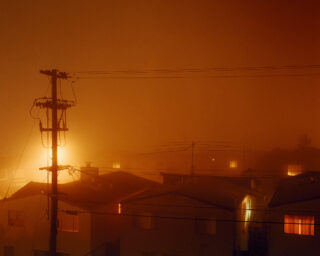

I then matched their photobook choices to nine people in my life who share a passion for visual culture and about whose opinions I am curious. On a very simple level, I thought they would appreciate the book that I was selecting for them and would write with subjective energy. My deep thanks to Helen Cammock (London), Bruno Ceschel (London), Iñaki Domingo (Madrid), Lorenzo Durantini (London), Colin Greenwood (Oxford), Takashi Homma (Tokyo), Karol Hordziej (Krakow), Owen Kydd (Los Angeles), and Aaron Schuman (Somerset) for writing their reviews with such flair and speed. Collectively, I think their reviews convey personal rather than generalized experiences of a selection of the most interesting new photobook titles. The idea of photobooks as an “experience” is reflected in the inclusion in this issue of two top-five lists of sites for such unreconstructed pleasure. San Francisco–based Darius Himes offers his choice of Californian photobook delights and I offer you my favorite five London sites of education in photography’s book form. Jason Fulford and Richard Misrach’s conversations in this issue are accompanied by an artist project, created with their fellow Bay Area members of Library Candy, that is this issue’s centerfold. Their round-robin group “portrait” dovetails nicely with the emphasis on friendship and collaboration evidenced throughout these pages. Finally, I want to thank Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin for their beautiful and heartfelt eulogy to Gigi Giannuzzi. Never did someone better represent the passion and originality of the incredible world of photobooks.

Charlotte Cotton is a writer and curator. Her books in clude Imperfect Beauty (Victoria & Albert Museum, 2000), The Photograph as Contemporary Art (Thames & Hudson, 2004, 2009, 2013) and the exhibition catalog Photography Is Magic! (Daegu Photo Biennale, 2012). She has initiated books, including Guy Bourdin (Victoria & Albert Museum, 2003), Shannon Ebner: The * as Error (Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 2009), Words Without Pictures (Los Angeles County Museum of Art/Aperture, 2010), and Phil Chang: Four Over One (Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 2010).