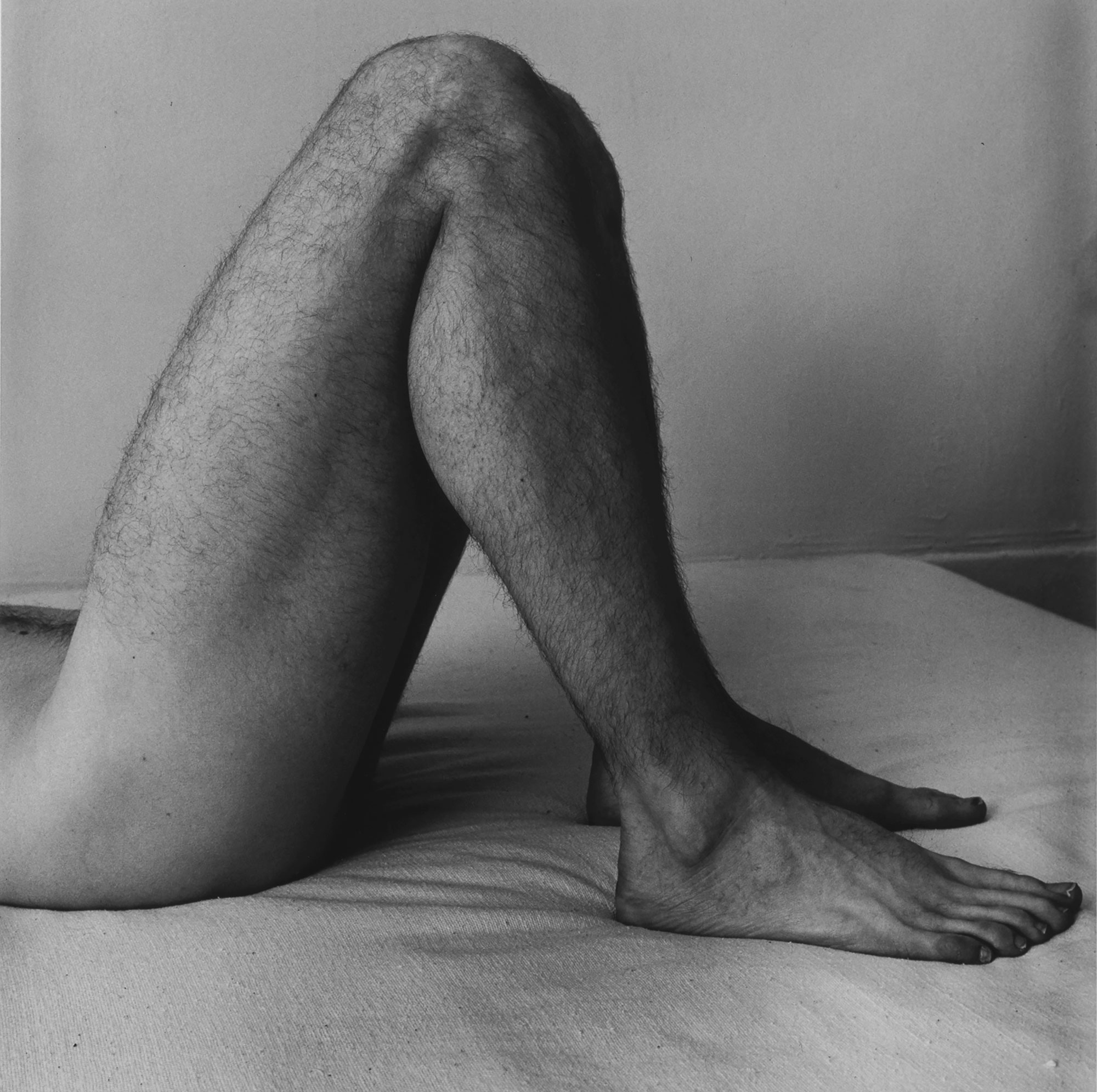

Peter Hujar, Paul’s Legs, 1979

Courtesy the Peter Hujar Archive LLC

While browsing The Shabbiness of Beauty (MACK, 2121), in which the artist and writer Moyra Davey places her images among those by the late photographer Peter Hujar (“a risky act,” as she puts it), I thought of a line from Davey’s 2008 essay “Notes on Photography & Accident”—written in an attempt “to rekindle a desire to make images,” and included in her recent collection of essays Index Cards (2020). The essay wanders wonderfully, but circles back to four authors: Roland Barthes, Walter Benjamin, Janet Malcolm, and Susan Sontag. “Malcolm’s perceptions thrill because they signal ‘truth’ in the way that strange, eccentric details nearly always do,” Davey writes.

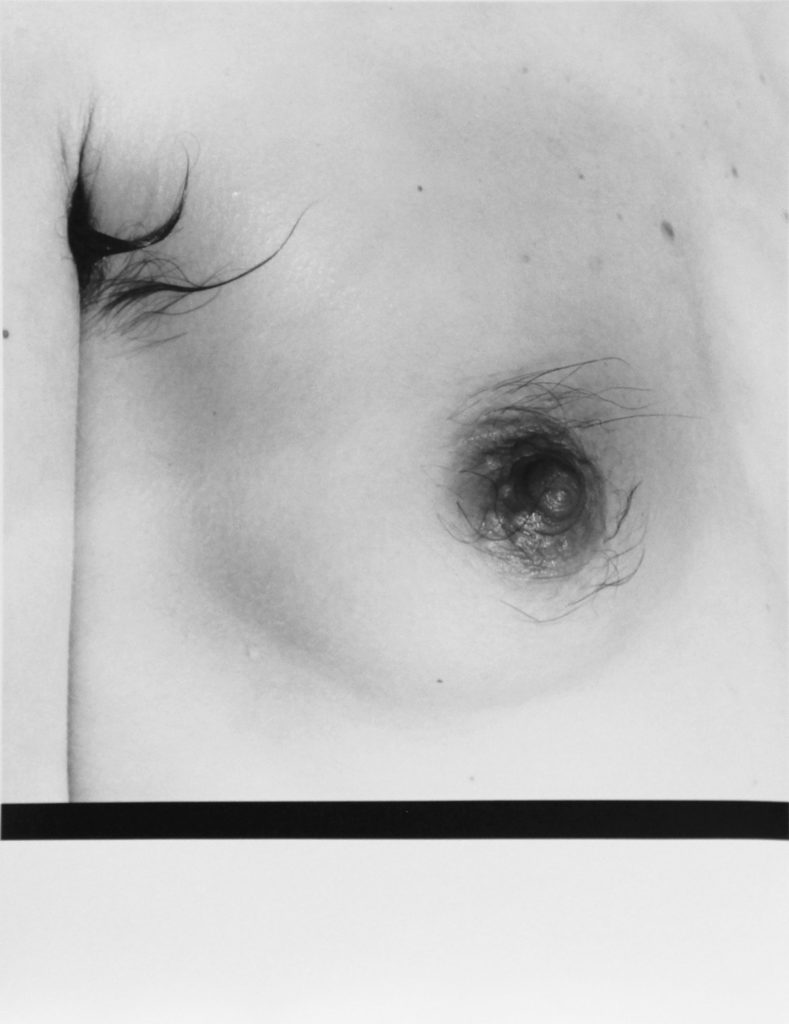

Courtesy the Peter Hujar Archive LLC

One can apply this notion to photographs. “Strange, eccentric details” help conjure a sense of honesty, of the oppressive mask of polite life slipping, and of a conspiratorial association between the viewer, whoever is revealing something in the photo, and whoever saw fit to capture it, to celebrate it. The warped or broken or peculiar elicits a tenderness—a greater awareness of the act of looking than when one skims the beautiful or the glossy. “Strange, eccentric details” suggests a breaking of some code; a sense of speaking up, shrugging off, being oneself. Hujar’s photographs, both the iconic and the lesser known, which Davey focused on for this project, are full of such details: a mustached artist posing with what looks like two bloody human stumps (it’s Paul Thek, Hujar’s once-boyfriend, preparing his 1967 work Death of a Hippie); or a body of water that looks somehow human—a face, a mouth, appearing in the waves.

Hujar presents his subjects with dignity, showing them both as they are (maybe young and gorgeous, maybe dying) and as they could be (sexual, weird, base, pensive) on a whim. Perhaps this is why Hujar is so great at photographing animals, capturing both the often amusing reality and the majestic possibility of the creature without making the image fetishist or twee. One is simply getting a good, honest look at a chicken. Truth, again. “Animals don’t hold still, except for Hujar,” writes Davey.

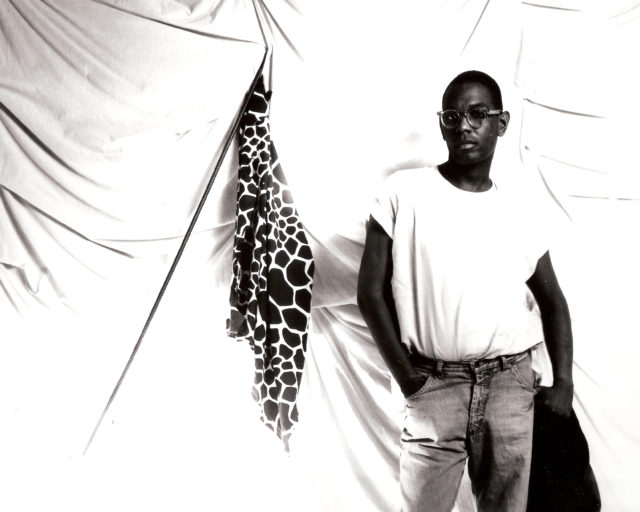

Courtesy the artist

Davey’s work is also about truth. Her long focus on the everyday has, to me, read as a desire to get to the bottom of things, to leave nothing as small as a stone unturned. It’s about paying attention. Her images in this book are interspersed, with no captions until the end, meaning one sometimes struggles to separate one artist’s work from the other’s, which is the whole point. Davey defers to Hujar’s preferred genres—animals, water, New York City, bodies, babies—and her pictures are rich with the same notes of incongruity or deviation. A dog looks oddly pensive, friends flex their unique forms, dark armpit hair curls elegantly.

The Shabbiness of Beauty, the result of a show at Galerie Buchholz in Berlin, is about discussion and dialogue, which makes sense for Davey, an artist who works across writing and photography, often using one to elaborate or spark the other. And yet, it is also about being present; about things (real things, things that are happening before the camera), perhaps more than it is about ideas. It is about consumption (which, as Sontag reminds us, photography always is), and about how we look at images to feed and nurture ourselves.

Courtesy the artist

In mining the Hujar archives, Davey shows us how we all build a sense of who we are through adulation and imitation (through feeling in step with our heroes), and that our past selves can be found as much in the worlds of others (their pictures, writings, notes, songs) as among the memorabilia of our own acts of creation: “Dipping into the archive is always an interesting, if sometimes unsettling, proposition,” Davey writes in “Notes on Photography & Accident.” “It often begins with anxiety, with the fear that the thing you want won’t surface. But ultimately the process is a little like tapping into the unconscious, and can bring with it the ambivalent gratification of rediscovering forgotten selves.” Clearly, various selves also emerged in her trip through Hujar’s history.

The Shabbiness of Beauty is about intimacy and the politics of reflection, which makes sense given the various critiques Davey has made about the contemporary mood for photographs that are giant, egotistical. (“So much of what we see in galleries is responding to the imperative to overproduce, overenlarge, overconsume,” she writes in “Notes on Photography & Accident.”) The Shabbiness of Beauty is quiet, deliberately; it invites speculation, time. As Eileen Myles writes in an essay in the book, “It makes sense that Moyra Davey would wind up expanding into writing—out here in art everything is given (supposedly) but in writing you can’t see the intention. Visual art is mapped on the out there. Writing’s like a cat. I would say Moyra’s a cat photographer.”

Courtesy the Peter Hujar Archive LLC

Hujar never clamored for attention by serving up the obvious (a reason many critics have given for why Robert Mapplethorpe, not Hujar, got the buzz in his lifetime). Hujar never victimized his subjects by feeding the urge to capture their victimization. There is too much respect. These are his friends, his world; him, partly. “We’re here, I’m here,” his pictures seem to say. As Davey writes: “In the 1960s and early 70s, Hujar sometimes preserved the black frame line around his pictures, and said: ‘to print the film frame [implied]: this is not a painting, this is photography. This negative has an edge . . . [it’s] an honesty thing . . .’” The implication: this photograph is something that was made, as well as something that happened. There are two distinct timelines—the one captured in the image, and the one that led to the image’s creation. Such a note from Davey suggests that this is a project about the process of things, about the act of making; the “behind the scenes,” a phrase that has so successfully transcended into marketing speak that it has lost its inference of “truth”—to go back to Malcolm.

But that is what’s at play in The Shabbiness of Beauty, a project first and foremost about truth, about honesty and, to a lesser but equally important extent, the performance of that honesty (not always an oxymoron); the attempt to show the progress, the influence, the relevant factors. Indeed, writing on her style, and that of some of the figures who cross between her and Hujar’s worlds, Davey says, “we are all self-consciously trying to signal that what’s going on behind the camera—the emotional register, the labor register, the thinking register, the mechanical register, the risk factor—is to us as important as the image itself.”

Courtesy the Peter Hujar Archive LLC

Davey continues by claiming that Hujar was “the opposite. Without self-regard, he gifted it all to the subject and the image through patience, framing, razor-sharp focus and crystalline lighting. He apparently gave no direction. . . . He waited for them to give to him whatever it was they were going to give, and then he took it—and after the wizardry of the darkroom, gave it back.” But to me, Hujar’s presence pervades his images. They are palpably sensitive. They summon the spirit of the author; his life, politics, and process; the specter of someone generous outside the frame. That presence is summarized by the title of Nan Goldin’s 1989 curated show Witnesses: Against Our Vanishing at Artists Space in New York, which featured Hujar, alongside close peers such as David Wojnarowicz, and which Davey once visited. This book is another gesture against vanishing, against the idea that Hujar’s work will only be a statement on its own time. In making the images into something new, Davey highlights how Hujar’s work continues to morph, to comment, and to be seen afresh.

The Shabbiness of Beauty: Moyra Davey & Peter Hujar was published by MACK in April 2021.