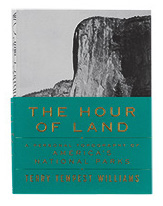

Peter Kayafas on Terry Tempest Williams, The Hour of Land: A Personal Topography of America’s National Parks

America is defined as much by its open spaces—where the hand of man is invisible or only circumstantially present—as it is by convenient mythologies, historical triumphs, or architectural marvels or atrocities. This year, the hundredth anniversary of America’s National Park Service is marked by numerous publications and a variety of celebrations of the public places under its stewardship. For those of us lucky enough to have had the time and facility to explore the parks, we can acknowledge that such adventures have caused unexpected changes in how we see, and in how we see ourselves.

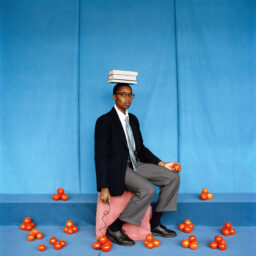

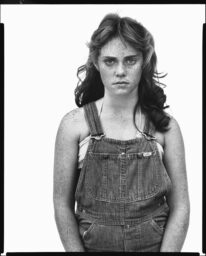

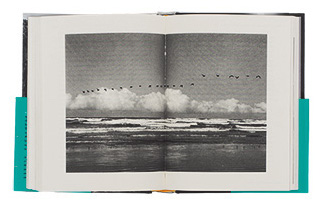

The Hour of Land is a book that uses a dozen of America’s fifty-eight national parks as inspiration for heated, personal introspection about what we have come to stand for as Americans. It is a memoir, a manifesto, a lament, a poem, an education. It is also an unconventional photography book. The author, Terry Tempest Williams, states early on that the twenty-four photographs she chose (with the curator and gallerist Frish Brandt) “create an emotional landscape alongside the physical one explored through each park in this book.” This group of pictures, spanning a period from the 1870s to present, is not what you might expect of a book about our national parks. There are a couple of the predictable (and great) photographs by Carleton Watkins and Ansel Adams, but the rest are as surprising a group as they are specific to the author’s taste.

Though this book is mostly text-driven, the suite of photographs plays an essential (and rewarding) role that is consistent with Williams’s intensely personal relationships with the places about which she writes. Collectively, these pictures remind us that a photographer is responding to the way the world looks in a way that is as individual as it is when a writer describes her experience; either result, when profound, is both intensely personal and universally relevant.

Though this book is mostly text-driven, the suite of photographs plays an essential (and rewarding) role that is consistent with Williams’s intensely personal relationships with the places about which she writes. Collectively, these pictures remind us that a photographer is responding to the way the world looks in a way that is as individual as it is when a writer describes her experience; either result, when profound, is both intensely personal and universally relevant.

It is no accident that Yellowstone, the first national park, was founded in 1872, during the same period when the government-sponsored U.S. Geological Survey was underway. That project’s photographers, including Timothy O’Sullivan, William Bell, Carleton Watkins (whose 1861 Yosemite photograph is on this book’s cover), William Henry Jackson, and a few others, would provide a sweeping, highly detailed survey of what the landscape of the United States looked like at the height of the so-called Westward Expansion and widespread European settlement. The resulting photographs, and others from similarly ambitious projects, have been continually published and presented in the name of conservation. As a result, photography has played an essential role in the creation and preservation of the parks. The spirit of exploration that has been the lifeblood of the photographers included in The Hour of Land is also what motivates Williams, both in her writing of this book and in her life, which she has dedicated to advocacy for the land through her teaching and activism. “I believe that necessity drives us to improvisation where improbable and sustaining gestures create moments of grace that take care of us,” she writes.

Don’t buy this book expecting to read a self-congratulatory celebration of how great America’s “greatest idea” is. In fact, this book is something of a call to arms, and a reminder that we face the difficult challenge of ensuring that our public lands are available to everyone in the future. It is also a reminder that many of the parks exist at the expense of the Native peoples who lived on the land for many, many years before the idea of public lands even existed. To be sure, The Hour of Land is a book that forces a collision between the successes and failures of federal land management, environmental shortsightedness and corporate criminality, and the need for people to have the courage to preserve.

Williams writes with a directness and candor that imbue her observations with an authority that can only come with genuine introspection. Like the photographers represented in this book, who depict their own relationships with the great collective spaces where we may find our most consistent national identity—the positive and the negative, the known and the unknowable—these stories of experience and revelation provide hope for our future. “No matter how much we try to manage and manipulate, orchestrate, or regulate our national parks, they will remain as the edge-scapes they are, existing on the boundaries between culture and wilderness—improvisational spaces immune to the scripts of anyone,” Williams writes. She compels us to go see what is ours—to learn from and be humbled by it, and to take responsibility for it. This is, thankfully, a hopeful and optimistic book. Because after all, what is the alternative? As Williams says, “Perhaps that is what parks are—breathing space for a society that increasingly holds its breath.”

Peter Kayafas is a photographer, publisher, curator, and director of the Eakins Press Foundation. He is a visiting associate professor of photography at Pratt Institute, Brooklyn. peterkayafas.com

Terry Tempest Williams

The Hour of Land: A Personal Topography of America’s National Parks

Sarah Crichton Books and Farrar, Straus and Giroux • New York, 2016

Designed by Abby Kagan

6 x 8 1/8 in. (15.4 x 20.8 cm) • 416 pages

24 black-and-white images • Hardcover with bellyband

us.macmillan.com/fsg