PhotoBook Lust: Olivier Richon on Paul Nougé, Subversion des Images

This is a web exclusive from the feature “PhotoBook Lust,” a collection of writing on photobooks and desire by artists, curators, and writers, first published in The PhotoBook Review 006. Read the Lust introduction by guest editor Bruno Ceschel.

PBR 006 will be shipped with issue 215 of Aperture magazine. Subscribe here.

Paul Nougé

Subversion des Images

Les Lèvres Nues

Brussels, 1968

Paul Nougé was a writer, a poet, and an intellectual. The nineteen square photographs in this small book were all made over the course of three months, from December 1929 to February 1930, with a simple amateur camera.

I first discovered Subversion des Images, this Surrealist manifesto for a different use of photography, in an exhibition of twentieth-century Belgian art at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris in 1991. I did not know at the time that the work had been produced as a book by the Belgian publishing house Les Lèvres Nues—“the naked lips.” No wonder then that these lips would encourage slips of the tongue, the pen, and the camera. Ten years later I finally managed to get a copy of the book, not without difficulty. It has now acquired the value of a fetish object.

My copy of the book still has its rice-paper wrap, so the cover looks like an image seen through frosted glass. The quality of the printing is basic; only the thickness of the paper indicates that it is a picture book as much as an essay. Although the work appeared in Surrealist journals, it was published as a book much later, in 1968. Only 230 copies were made.

For me, this book is exemplary for many reasons. It fits into a jacket pocket and its content is, as the title indicates, subversive. Photography is not here in the service of realism, documentary, or the morbid rituals of family life, but instead is in the service of dreamwork where image and language are intertwined, arguing for the rhetoric of objects.

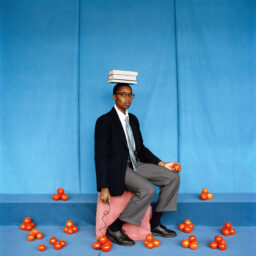

Here, the camera is akin to a typewriter, used to produce a visual manifesto about the appearance and disappearance of objects. Nougé was a close friend of René Magritte, who figures in some of the photographs. He was also responsible for many of the titles of Magritte’s paintings. (For Nougé, as for Magritte, the title always came after the image, and therefore could always be revoked.) It is clear that there is a visual conversation going on between the two artists in Subversion des Images, more marked in some images than in others. All the pictures are scenes from inside a home. Most of the subjects look like they’re sleepwalking or hypnotized, and objects have an uncanny presence. This is the world of the inside, of interiority. Photography, in the words of Dalí, is conceived as a creation of the mind.

In these photographs, we have a condensed version of Nougé’s conception of the object: it must be separated from the thick universe of things. When objects are isolated and lose their functions they become signs, images; even something as banal as a piece of string can be turned into an incomprehensible thing. The same could go for words, which can be equally isolated from the mass of language that obscures their objectness. Alternatively, as with ellipses in a sentence, the object can be removed entirely, like the “glasses” in the photograph of two drinkers at a table: holding the air in the shape of two missing vessels, their hands appear to be living things, attempting to touch each other.

The back cover of the book shows an arm coming from behind an almost-closed door. The index finger points toward the edge of the frame, which cuts and isolates the visual field to turn it into an image. But this pointing also brings us back into the book, inviting us to read it again from the end—as if walking backward to get ahead.

—

Olivier Richon lives in London, where he is a professor of photography at the Royal College of Art. He is currently writing a book about a photograph by Walker Evans for Afterall Books’ One Work series.