Picturing Obama

How have photographs defined a transformative presidency?

Pete Souza, Inside the White House, May 8, 2009

Aperture is deeply saddened by the loss of Maurice Berger (1957–2020), whose urgent writing about race and visual culture defined a standard of excellence for the photography community and beyond. Here, we revisit his essay for Aperture, issue 223, “Vision & Justice.”

Courtesy Damon Winter/ The New York Times/Redux

“What really exercises my mind is not this hypothetical day on which some other Negro ‘first’ will become the first Negro President. What I am really curious about is just what kind of country he’ll be President of.”

—James Baldwin, “Nationalism, Colonialism, and the United States: One Minute to Twelve,” 1961

The photograph by chief official White House photographer Pete Souza of President Barack Obama boarding Air Force One in Jamaica last year is at once mystical and trite. As the president waves to the crowd below, the rainbow that appears behind him seems to issue from his outstretched hand. “With hard work and hope, change is always within our reach,” tweeted the White House along with the photograph, echoing themes that go back to Obama’s first presidential campaign. Although Souza has claimed that the image was largely the result of luck, his admission that he “ran under the wing of the plane to try and line up where the President would be when he waved goodbye” suggests the degree to which the image was premeditated.

The photograph’s calculation attests to the lengths this administration has gone to in order to control the public image of the president and First Lady, a vigilance motivated, in part, by the need to push back against the unprecedented bigotry and vehemence of their adversaries. Admired by supporters and maligned by foes, political leaders inevitably serve as lightning rods for public opinion. Depictions of them appear in myriad forms and are shaped by multiple and often contradictory motives, from documenting official duties to disseminating partisan propaganda. But this president’s race has rendered his image vulnerable to extreme manipulation and distortion. Right-wing and white supremacist media outlets have habitually altered, taken out of context, and falsified photographs of him in order to promulgate a range of racist stereotypes and myths. Intent on undermining Obama’s authority and legitimacy, they have portrayed him as an inept neophyte, an angry black man intent on avenging historic injustices, a foreign-born Muslim, a liar, and, at their most debased, a primate.

© Pete Souza/The White House/Handout/Corbis

Depictions of Michelle Obama have been similarly fraught. Tabloids have shown her as a fist-bumping black militant bent on destroying white patriarchy and have doubted her fitness to be First Lady. “I was . . . the focus of another set of questions and speculations; conversations sometimes rooted in the fears and misperceptions of others,” she recalled last year. “Was I too loud, or too angry, or too emasculating? Or was I too soft, too much of a mom, not enough of a career woman?” Like her husband, the First Lady has also been subjected to more subtle slights. Mainstream publications, perhaps taking their cue from a cautious White House concerned about perceptions of her as strident, have downplayed her formidable intellect and distinguished career before becoming First Lady, focusing instead on her roles as dutiful mother in chief, health advocate, and fashion icon.

There is no doubt that affirmative images of the Obamas have played an important role in the struggle for racial equality and justice. They have defied stereotypes, established new role models, bolstered confidence and self-possession, and challenged expectations about political and cultural power. But the White House’s vigilant management of these images, whatever the motivation, has a complicated history. For one, it has raised concerns among photojournalists who have routinely been denied access to the president, restrictions with serious long-term implications. In 2013, a number of news organizations, in a letter submitted to White House press secretary Jay Carney, made clear their dismay: “As surely as if they were placing a hand over a journalist’s camera lens, officials in this administration are blocking the public from having an independent view of important functions of the Executive Branch of government.”

Also, the White House and its supporters have at times been drawn into a battle of stereotypes with their detractors, countering right-wing myths with left-wing ones. This problem has been especially true of depictions of the president. To liberal admirers, he has been an object of fascination, the epitome of cool. To the White House, as Nicole Fleetwood has observed, he has served as a paragon of black masculinity as he implores African American men to take “responsibility as fathers.” To Senator Joe Biden, before he joined the Democratic ticket, Obama was “storybook” perfect—a mainstream African American presidential candidate who was “articulate and bright and clean and a nice-looking guy.” To the mythmakers of the 2008 campaign, he was a messiah who would unite a divided nation and heal its racial wounds.

© David Burnett/Contact Press Images

This myth was enabled by the most notable image of that election: Shepard Fairey’s Hope poster, distributed independently by the artist and then with the approval of the Obama campaign. Hope depicted the man who would soon be president as confident and dynamic. But the band of white paint that raked across his face, in a picture devoid of the color brown, implied something else: that Obama was beyond race, a “postracial” politician, half African, half white American, unburdened by the legacy of slavery and segregation. This idea helped to placate apprehensive white Democrats in the campaign against Hillary Clinton—many of these voters, their lives largely segregated, were plagued by racial angst. In Fairey’s ingenious poster, Obama was depicted as black and white, race specific and race neutral, a blank screen onto which voters were invited to project their dreams and aspirations. Obama the man was transformed into Obama the myth—a mystical leader, who, for the price of their support, allowed voters to assuage their guilt and feel good about themselves.

Implicit in this purposely iconic imagery was the idea that the senator from Illinois was uniquely qualified to bestow upon white America a divine gift: racial “atonement and redemption,” as Barbara Ehrenreich wrote during the campaign. Thomas L. Friedman, writing in the New York Times, imagined a similar possibility: the election of the first black president had ushered in a “different country,” where we could “start afresh . . . from a whole new baseline,” despite the persistence of racial prejudice. “And so it came to pass that on Nov. 4, 2008, shortly after 11 p.m. Eastern time, the American Civil War ended,” Friedman proclaimed in language befitting the Bible, a breakthrough not possible until “America’s white majority actually elected an African American as President.”

If the seven and a half years of racial discord, violence, and murder since Obama’s election have not been sobering enough, a simple statistic concerning the 2008 election results reveals the hollowness of this claim: America’s white majority, in fact, gave the bulk of its support to white men, affording Obama only 43 percent of its vote. In Obama’s race for reelection in 2012, the number was even lower, at 39 percent. The president’s victories proffered neither a sweeping repudiation of white racism nor the end of racial divisions. Nevertheless, as Friedman’s argument suggests, many white Americans, with much to prove about their racial attitudes and behavior, believed that the election of the first black president was principally about them. But Obama’s victory owed more to other forces: a motivating and gifted nominee, the promise of change, and rapidly evolving demographics. In the twenty-first century, a national candidate of color could prevail without a majority of white voters, a sign of the latter’s inexorable decline toward minority status.

Courtesy epa/Chip Somodevilla

Seen in this context, one of the most realistic and hopeful implications of the 2008 election was the extent to which Obama inspired a robust electoral majority, consisting principally of people of color, other minorities, and urban whites, to elect a commander in chief who better reflected their diversity. If this milestone was not always stressed by the president or the campaign, for fear of alienating white supporters, it nonetheless has motivated or underscored some of the most inspiring images of the Obama presidency.

A sense of hope and possibility infuses Pete Souza’s 2009 image of the president interacting with five-year-old Jacob Philadelphia, for example. The child’s father, leaving the White House after two years of service on the National Security Council, had asked for a family photograph with the president. After those pictures were taken and the family was about to leave, Jacob had a question for Obama: “I want to know if my hair is just like yours.” “Why don’t you touch it and see for yourself ?” the President replied, leaning forward. As the child hesitantly patted his head, Obama asked him what he thought. “Yes, it does feel the same,” said Jacob. Souza’s poignant image affirmed the extraordinary symbolic power of the Obama presidency as well as its potential to challenge stereotypes. Against a relentless backdrop of pessimism and deprecating myths about black men, a little boy had come to realize that he, like the president who bowed before him, could one day achieve his dreams.

Historically, images of hope, accomplishment, and self- assurance have been influential in achieving stability in the black community and social justice in the nation at large. They have bolstered the self-esteem of African Americans, steeling them against a relentless tide of negative images and withering stereotypes, just as they have challenged white Americans to rethink the misconceptions that underwrite their prejudices. Almost since its introduction in the United States, photography has done more than just document the reality of racial prejudice and oppression: it has motivated a people, even during periods of extreme violence and repression, to create alternative and affirmative images of themselves and thus take control of how they are seen by others. As Deborah Willis and Barbara Krauthamer observe in their groundbreaking 2012 book Envisioning Emancipation: Black Americans and the End of Slavery:

These wide-ranging photographs can be seen as the embodiment of the history and memories of slavery, emancipation, and freedom. They constitute an archive of black people’s seen and unseen lives, their spoken and unspoken experiences. . . . They offer powerful evidence of how black women, men, and children saw themselves and each other: as dignified, beautiful, creative, intellectual, energetic, diligent, steadfast, powerful, and free.

Courtesy the artist

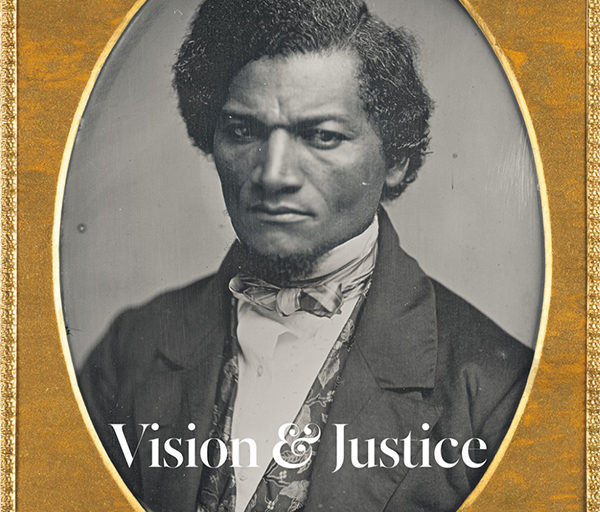

The representation of black political and cultural leaders—from Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman to Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and Malcolm X—has played a significant role in this history. Douglass believed that the broad “moral and social influence” of photography was more powerful in transforming national culture than “the making of its laws.” An ex-slave who became one of the leading abolitionists and crusaders for racial equality and justice, Douglass was also the most photographed American of the nineteenth century. His commitment to being pictured was coextensive with his social activism: images of black role models and leaders, he argued, had the potential to challenge racial biases and empower people of color.

As the editors of Picturing Frederick Douglass: An Illustrated Biography of the Nineteenth Century’s Most Photographed American (2015) write, the sheer number of public portraits of Douglass, “from his earliest known photograph as a young man with an Afro, circa 1841, to the postmortem portrait fifty-four years later, conveys not only Douglass’s faith in photography but his understanding of the public identity he was crafting.” By disseminating pictures of himself that were nuanced and continually evolving, Douglass was effectively undermining the stereotypes and clichés that robbed human beings of their individuality and humanity. This transformative understanding of selfhood—and the social possibilities of a nascent visual technology—helped destabilize the rigid misperceptions that justified racism, perpetuated slavery, and endangered the survival, confidence, and self-possession of African Americans.

Today, with stereotypes continuing to perpetuate racism and harm people of color, it is impossible to underestimate the symbolic importance of the myriad photographs of President Obama. But the unique circumstances of his presidency have also complicated the ability of his image to achieve the broad disruption of stereotypes that Douglass envisioned. Ultimately, the public image of every president is largely reduced to the superficial clichés that inform popular conceptions of them: John F. Kennedy as the tragic hero of an unattainable Camelot, for example, or Richard Nixon as the deceitful Tricky Dick. From the beginning, Obama’s race has constituted the abiding adjective of his groundbreaking presidency, regardless of whether it has impacted his policies and conduct in office. Ultimately, he will always be known as the first black president, a fact that has also exposed him to other, more insidious forms of stereotyping. Thus, his public image has been constricted by the mythmaking endemic to his job, the media, and his race, as well as the magical thinking that has burdened him with unattainable expectations. Nearing the end of his tenure, and despite remarkable achievements, Obama remains, for many, the mystical cipher of the Hope poster or the foreign-born imposter of right-wing fantasy: a one-dimensional symbol of our loftiest ambitions or our most venomous fears.

Courtesy REUTERS/Gary Hershorn

The most illuminating and inspiring depictions of the president, like those of the First Lady, transgress this limitation, subtly challenging stereotypes with images that are complex, nuanced, and, to a great extent, spontaneous. Rejecting political clichés and symbols, these pictures return to the Obamas the humanity lost not only to seditious rhetoric, but also to veneration or the routine give-and-take of partisan politics. The photograph of little Jacob, for example, was neither staged nor planned, as its awkward composition, unintentional cropping, and blurred foreground affirm. Its unguarded interaction reveals a nimble, sensitive, and racially aware president, a leader who has inspired, by his own example, millions of Americans to imagine a positive and just future. Similarly, a photograph taken by Damon Winter during the 2008 campaign shows Obama not as a rainbow whisperer but rather as a vulnerable human being, drenched by rain but determined to be there for the crowd who turned out to support him in Chester, Pennsylvania. Another impromptu image from the campaign, taken by photojournalist David Burnett, reveals a thoughtful, poised, and introspective Michelle Obama absorbed in conversation as her husband looks on, an inversion of the conventional image of political leader and adoring spouse.

In an age when millions of photographs are posted on social media each day—and the camera endures as a vital weapon in the struggle for racial justice—it is important to remember that the authority to represent the president and First Lady belongs not only to political insiders or the media, but also to the people they serve. Whether amateurs with cellphones or renowned photographers, their take on the Obamas constitutes the ultimate commentary on how Barack and Michelle are being received and understood. Well before the White House released the picture of little Jacob, for example, the photographer Nona Faustine recognized the personal and historic significance of the proximity of Obama’s election to the birth of her daughter. Watching his first inaugural address on television, her newborn stirring in the foreground, Faustine did what generations of African American men and women had done before her: she picked up her camera and recorded for posterity the beauty and consequence of the moment. The photograph she took is at once intimate and historic, a testament to new possibilities and a touching declaration of hope. It is also a reminder that the prosaic can be monumental, quietly testifying to the faith, aspirations, and triumphs of a people.

This piece was originally published in Aperture, issue 223, “Vision & Justice,” Summer 2016.