Pieter Hugo on designer Garth Walker

As part of Photography As You Don’t Know It (Aperture, Winter 2013), we asked three photographers to select a photography-world figure whose contributions to the field have been overlooked. Here, photographer Pieter Hugo discusses the influence of South African design pioneer Garth Walker.

The first thing you need to know about Garth Walker is that he is completely unpretentious. The second thing you need to know about Garth Walker is that he is probably the leading person in African graphic design and typography. The third thing you need to know about Garth Walker is that he is an obsessive collector and loves all things photographic.

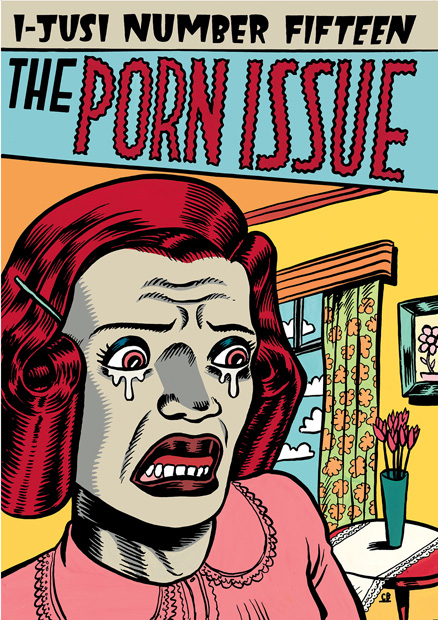

After working as a lackey for sixteen years at a repro house, Garth moved on and founded two of South Africa’s best-known graphic design studios: Orange Juice Design in the early 1990s, and more recently, in 2008, Mister Walker. When Garth started his first studio in 1994, he had no work and a lot of free time. He decided to start a design magazine called ijusi. At its nucleus it posed the question: “What makes me African and what does it look like?” To answer this, Garth filled the magazine with his collection of South African vernacular design and photography. After a few issues, it evolved to publishing submissions. ijusi has no writers or advertising. Each issue is themed: tattoos, porn, photography, etc. Collaborators find out about upcoming themes through word of mouth and send work to Garth. It is non-commercial and the paper is sponsored.

The timing of ijusi’s creation was perfect. South Africa had moved from an autocratic state to a democratic one, and there was an intense global focus on the scene here. Garth’s magazine became an entry to and an expression of this world by introducing South African designers, photographers, and artists to an international audience at a time when there wasn’t much else going on. Soon, ijusi became the South African design bible. Now Garth is widely regarded as the pioneer of post-1994 South Africa-rooted graphic design, and his projects have been pivotal in creating a South African visual identity—both in design and photography.

In addition to his activities as a graphic designer, Garth is a serious collector of photography. His image archive on South African vernacular street and township design is the largest extant, and covers literally everything, from gravestones to type, signage, and architecture. He has also supported many professional South African photographers, myself included, by buying photographic prints. He was one of the first people to buy prints from Jodi Bieber, Zanele Muholi, and Guy Tillim, and he collected works by Roger Ballen and David Goldblatt many years before it became fashionable to do so. One needs to remember that it is a relatively new phenomenon for public institutions to exhibit and collect contemporary photography in South Africa. In the apartheid years photography was relegated to a documentary role; its task was to urgently inform. Historically, it fulfilled the role of classifying people according to race and tribe, a device to categorize and exploit. Public institutions had little time for “art” photography. Much of the work Garth has collected, both by contemporary photographers and vernacular work, has subsequently been acquired by local and international museums and institutions.

Needless to say he has a fantastic eye, but it is important to stress that he also has modest means. He buys work that he believes in and has an emotive response to. He has never bought for the sake of investment. The work he buys, he lives with. His house in Durban is literally crammed with photographs. Although he is not directly linked to the “photo world”—which is why you, as an Aperture reader, have probably never heard of him—Garth Walker has been a trailblazer. He has played a crucial role in promoting South African photography through his early support for artists and his graphic design and publishing endeavors.

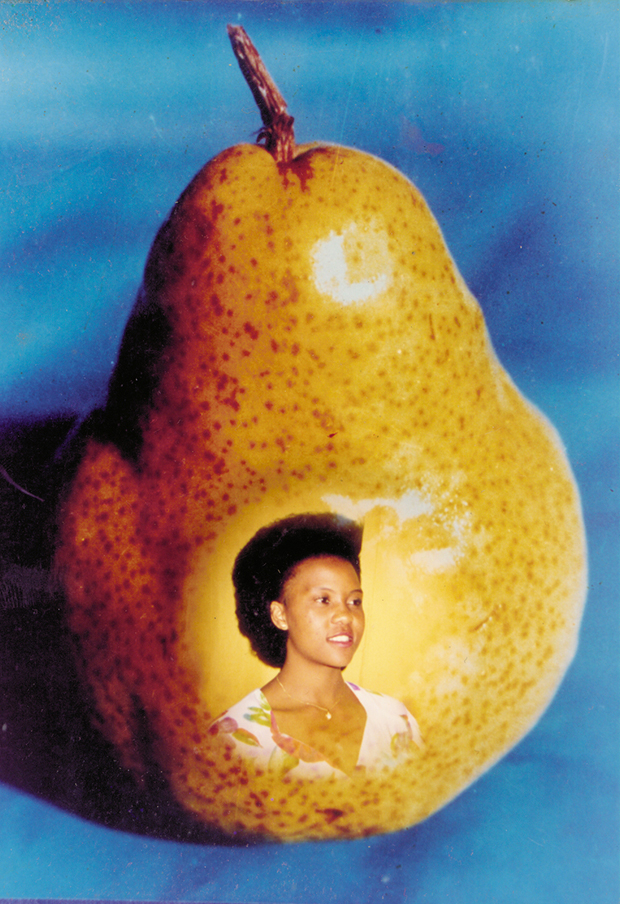

Composite portrait as found in the Sipho Khoza “Wedding and All Occasion Photographer” album containing examples of double-exposure portraits for client selection, late 1980s. Garth Walker Collection

Garth Walker, Composite Mandela illustration based on street vernacular imagery and found reference (digital illustration), 2010. Courtesy Garth Walker

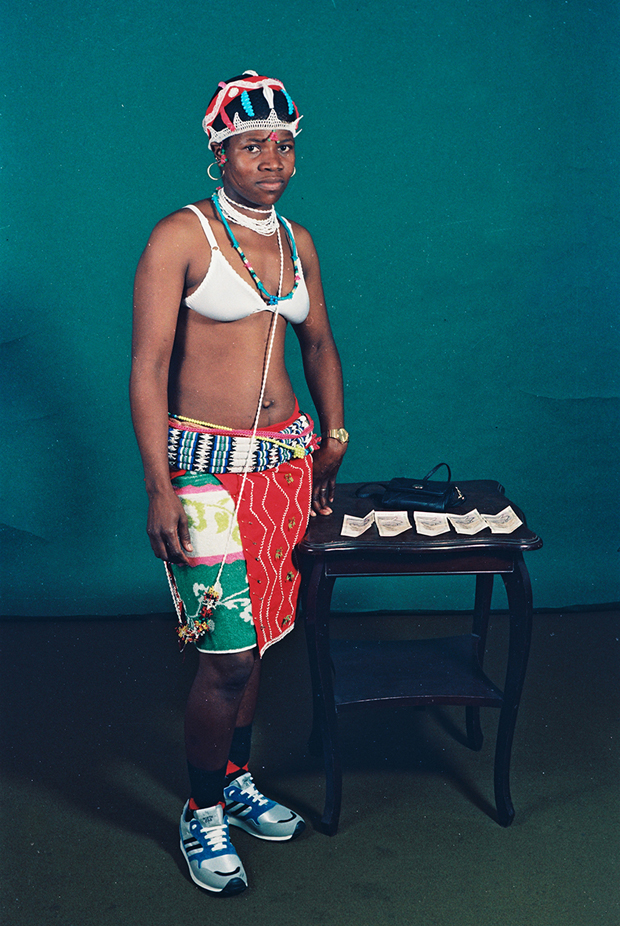

Zulu woman “coming of age” portrait, Vijay Singh, Lyric Studios, Tongaat South Africa, late 1970s. Garth Walker Collection

Cover of ijusi issue 19. The pinhole-camera photograph was made by students of the Visual Arts & Design Department, Vaal Triangle Technikon, Vanderbijlpark, South Africa, 2003. Courtesy Garth Walker

—

Pieter Hugo is a photographer based in Cape Town.