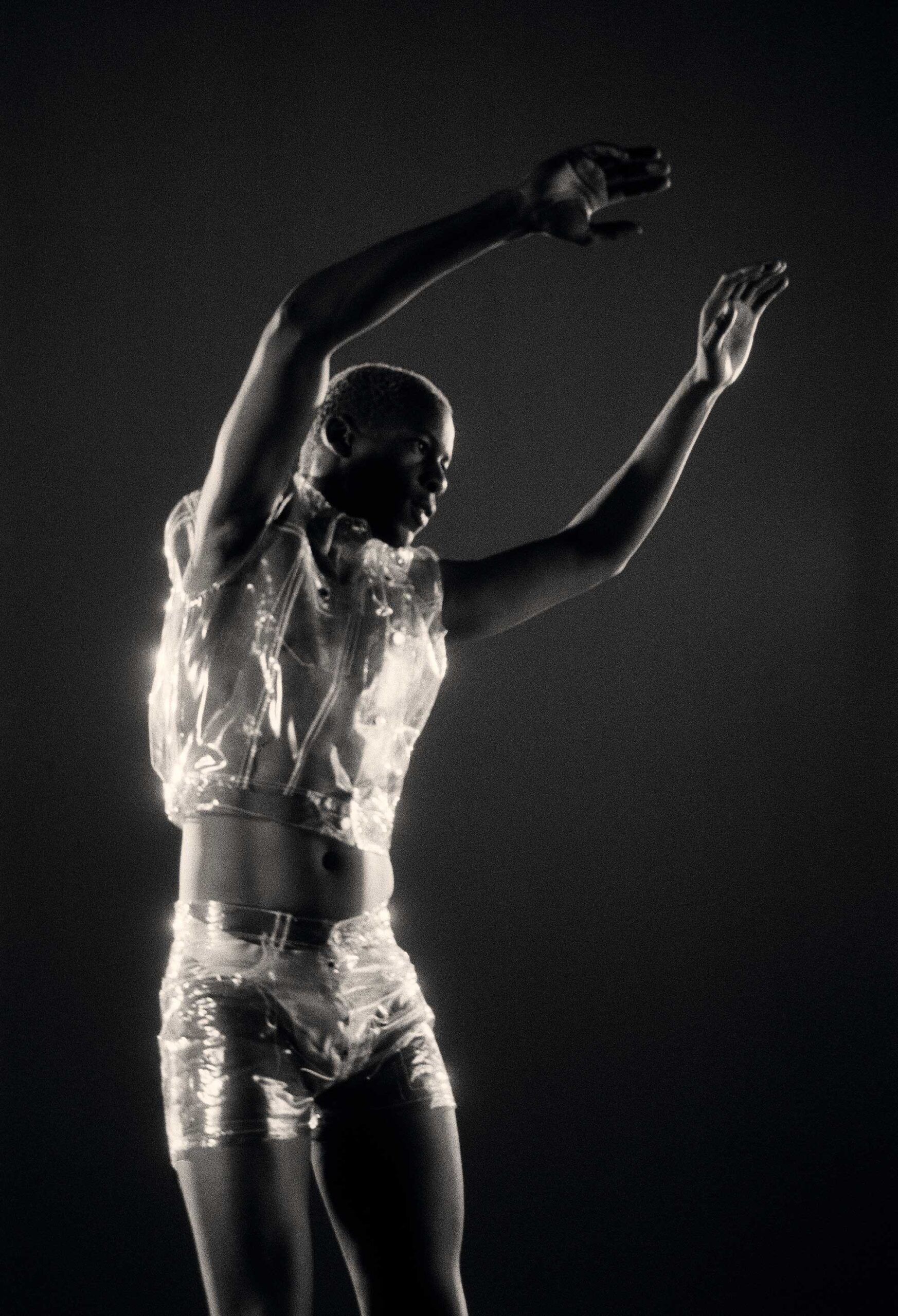

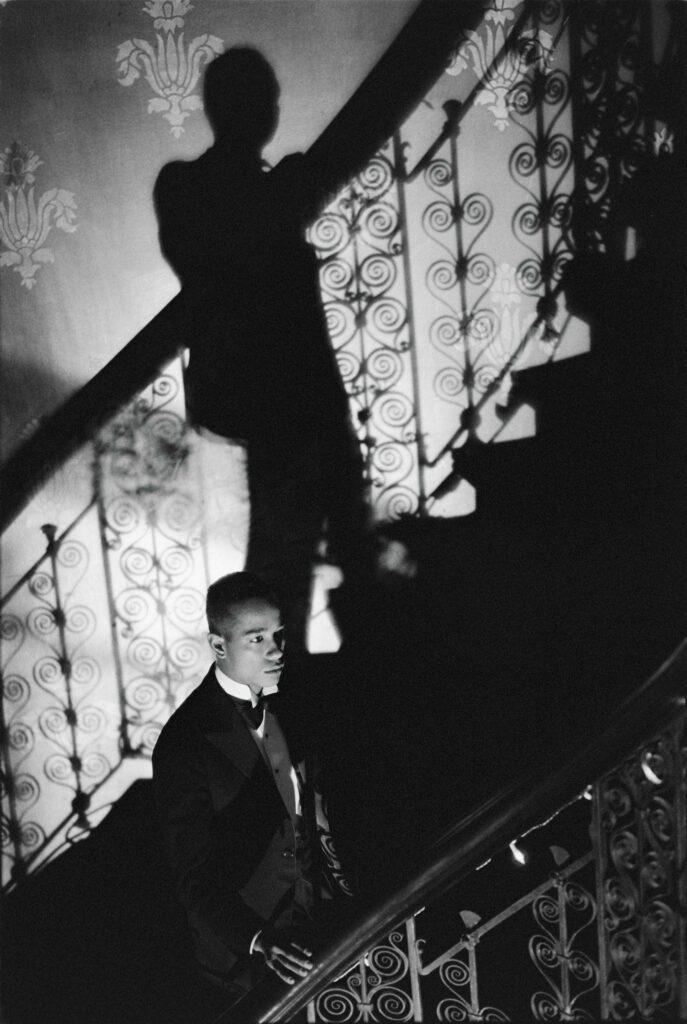

Isaac Julien, Trussed series, 1996

One of the most innovative artists of his generation, Isaac Julien rose to prominence in the late 1980s with the debut of his film Looking for Langston (1989), a lyrical meditation on the poet Langston Hughes. Looking for Langston, made collaboratively with the photographer Sunil Gupta and the cinematographer Nina Kellgren, is set in the atmospheric, reimagined world of Harlem in the 1920s. Evoking Hughes as a queer icon, Julien pushed expressions of black male desire into visual culture through what he calls the “aesthetics of reparation”—the creation of a space where images of different identities and races can exist and flourish. Here, Julien speaks about returning to his early work in Vintage, an exhibition of photographs that recently opened at Jessica Silverman Gallery in San Francisco.

Brendan Embser: For Vintage, why did you decide to turn back to your earlier film and video work in the form of still images?

Isaac Julien: A lot of this emanates from working on my MoMA catalogue, Riot (2013), which comes out of the work I’ve been undertaking in my studio. In the mid-2000s, we began looking at my archive and trying to get that into order. That’s where the first interest began in showing the Langston photographs. That felt like a work that was kind of important to resurrect because it had just been gathering dust in the vault!

Embser: In the exhibition, there are two scales for the prints.

Julien: Yes, these prints are showing two different kinds of photographic techniques—traditional gelatin-silver prints and larger-scale photographs, which are closer to the original cinematic experience of looking at the film. I wanted to make some larger-scale works from the series because, of course, new technology allows one to do that! I’ve been making photographic works in Germany, at Grieger in Düsseldorf—and I see the influence of that “New German Photography” school in my own practice. But, the Looking for Langston images were always meant to be images, which were shot both on Super 16mm film and on 35mm black-and-white film. All of the images made for both technologies were made to be seen at a large scale. There’s my premise.

Embser: Let’s go back to the origins of photography and the image for you. I’m thinking about the photographers you’ve mentioned, both in your MoMA catalogue and with regard to this exhibition: James VanDerZee, George Platt Lynes, and Robert Mapplethorpe. Were these the photographers you had in mind in the early part of your career? Or specifically when you set out to make Looking for Langston?

Julien: I know there’s a new documentary on Robert Mapplethorpe’s work, which I saw at the Berlin film festival, and it reminded me that my thesis, when I was at Saint Martin’s School of Art in London, was focused very much around Robert Mapplethorpe’s work. The thing I was trying to do, in the early ’80s, was to look for images that resonated with me. When I saw VanDerZee’s work, for example, I just knew it was very important in terms of vernacular of African American photography and black culture generally. So, it was when I was making Looking for Langston, when I was concentrating on the theme of the Harlem Renaissance, that my encounter with photography—with American photography, and with black-and-white photography in particular—became very important.

Embser: Robert Mapplethorpe is having a moment right now. Do you still feel a strong connection to his work?

Julien: I see a return to Mapplethorpe, and indeed a return to analog techniques in photography, as a kind of recourse to the way in which digital technologies have become “over-spectralized” to such an extent. We’re completely intoxicated by images. So, there’s that return. But certainly thirty years has passed, and that creates enough critical distance where you can look at a photographer like Mapplethorpe anew. It’s very much about periodization and the shift that time affords and enables you to have a different gaze upon works of his kind.

Embser: Do you see Looking for Langston in a genealogy of American portraiture?

Julien: Absolutely. That really comes out in the work. In Looking for Langston, it’s George Platt Lynes and black-and-white photography, which creates a kind of “cocktail”—VanDerZee is the strong aesthetic signature to the work. There are also all the other references—cinematic references to say film noir, or to the expressionism which belonged to German cinema, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari—that intersect the work. For all intents and purposes, the series in Vintage belong to a film set. So it’s also the lighting of Nina Kellgren, who shot the film, and the apparatus that cinema brings to the image, and the way you have to think about the black-and-white image in particular.

Embser: What was the nature of your collaboration with Sunil Gupta on Looking for Langston?

Julien: The nature of the work was similar to working with Nina. I’m always looking to make work with people who are technicians, but in the case of Nina, she studied sculpture at the Slade School of Fine Art, she made black-and-white photography, and she taught photography. Sunil is a photographer himself. I was in dialogue with both artists when I was making Looking for Langston as they were performing and working and shooting the film. And to some extent, I carry that practice on to this day. But, I would say, in Sunil’s work, we were interested in the way that he was pushing certain questions around gender and sexual identity, in the same way that I was, in Sankofa Film and Video and the Black Audio Film Collective. We have a lot of friendships from those days, which were committed to lots of different struggles that were taking place, especially around the AIDS crisis and the decolonization of queer culture, which was very much attacked by Thatcherite forces. There was a common bond that we had.

All photographs courtesy the artist and Jessica Silverman Gallery

Embser: Could you explain what you mean by “aesthetics of reparation”?

Julien: When we’re thinking about the industries of film and photography, we know that we’re dealing with a technology that is particularly non-neutral in the way in which black subjects, specifically, have been treated. Not only by the technologies themselves, which were aligned to lighter skin tones, but we know that the rules of representation—and the technologies of representation—have to be rewritten if you want to articulate a certain aesthetic. So, I always view the making of works as an act of reparation, aesthetically. It’s the undoing of a very forceful regime of dominant effects, which are quite a bombardment for any person of color growing up or being part of a generally dominant white culture, particularly in the photographic and cinematic industries. Making work is about how one can produce the aesthetics of representation, which is about creating and sustaining spaces for different images to exist of black subjects, of queer subjects, of working class subjects. In the work of Langston Hughes, for example, I see a strong sense of the aesthetics of representation. His work is very much about looking at black life and the aesthetics that get drawn out, such as in VanDerZee’s Harlem Book of the Dead, a photographic book which I looked at very closely in the making of Looking for Langston. In some senses, I’m looking to recreate a certain mise-en-scène, which had an inspiration from those photographic images and from black modernism.

Embser: You mentioned that you’re still working on your archive. But Riot contains a great quantity of photographs—it is an archive, in it’s own way. There are many pictures of the artists and intellectuals who surrounded you as you were making the works we’ve just discussed. Are you still thinking about another book project on your archives?

Julien: I’ve wanted to do a book on Looking for Langston. But, I think it would be fantastic to do a book just on the photographic side of my work, which of course includes lots of collaborators, such as Sunil Gupta, and also all the people I worked with on my films, such as Nina Kellgren. My work is rooted in photography. In the Vintage exhibition, that’s one of the things I’m trying to bring to the forefront.

Vintage is on view at Jessica Silverman Gallery, San Francisco, through June 11, 2016.