Chris Boot at the “Family” Aperture Gala, New York, 2018

Photograph by Sean Zanni/Patrick McMullan

This spring, after ten years of leadership, Aperture Foundation’s executive director, Chris Boot, is stepping down and returning to London. Boot joined Aperture in 2011, at a moment when the field of photography was experiencing a profound change. Would print publications survive the digital revolution and the nascent Instagram age? Would critical thinking and writing about photography be relevant when everyone with a smartphone could be considered a photographer?

Boot’s tenure at Aperture, and the output of publications over the last ten years, has answered these questions affirmatively—and definitively. The artists Aperture has published have earned accolades and international renown. LaToya Ruby Frazier, whose first book, The Notion of Family, was published by Aperture in 2014, won a MacArthur Fellowship. The Open Road: Photography and the American Roadtrip (2014) is a best-selling compendium, and the accompanying exhibition traveled extensively. Antwaun Sargent’s The New Black Vanguard (2019) has become a phenomenon in fashion and culture. And Aperture magazine, the foundation’s flagship publication, won a National Magazine Award for General Excellence and an Infinity Award for the landmark issue “Vision & Justice,” guest edited by Sarah Lewis.

Since the publication of “Vision & Justice” in 2016, Boot has been inspired by Lewis’s concept, derived from Frederick Douglass, that progress requires pictures. “That motivated me,” Boot says in this conversation with Brendan Embser, managing editor of Aperture. “It became a thread of Aperture’s work, thinking about photography’s positive role in shaping ideas of who we can be.”

Courtesy the Center for Creative Photography, Arizona Board of Regents

Brendan Embser: When Aperture was founded in 1952, the intention was to create a space for those who were committed to serious photography, and for some of the founders, photography was life itself. But your role hasn’t only been programmatic. You’ve had to keep the lights on. And when you joined Aperture in 2011, you were already a successful publisher, an editor. You had worked at Magnum; you’d had your own imprint. So what compelled you to move to New York and take on the job at Aperture?

Chris Boot: Well, it was a very interesting moment in photography in 2010, which is when I was appointed. It was a few years after the launch of the iPhone. Instagram had just started. We’d already had a revolution in photography in terms of production moving from analog to digital, and that had huge consequences. And now, there was this new revolution in the means of dissemination, which allowed everybody to be not just an image-maker and tell their own story, but to be a publisher and put their images out into the world.

I wasn’t really looking for a job when Aperture knocked. And then, it just hit me that it was exactly what I wanted to do—a calling. I started out in photography in community work and education and working around issues of representation. I’d gone on to Magnum, where I was representing photographers and developing global stories with them, and placing them in the media, and starting to do books. I started in publishing at Phaidon and then set up my own imprint, which I ran for ten years, editing and publishing books. My imprint couldn’t be scaled up, and I couldn’t meet the opportunities afoot in the emerging landscape. I felt I could bring all this experience together at Aperture. Aperture had this incredible legacy, and a scale to navigate new opportunities, and was ready to change. At its peak, it was the greatest photography publisher in the world. I wanted to try to put it back there.

Embser: It’s also relevant to ask—what kind of phone did you have in 2011?

Boot: [laughs] I forget. I don’t think I got a smartphone until I was in New York. I remember Lesley Martin, Aperture’s creative director, teaching me how to join Instagram. That must have been 2012.

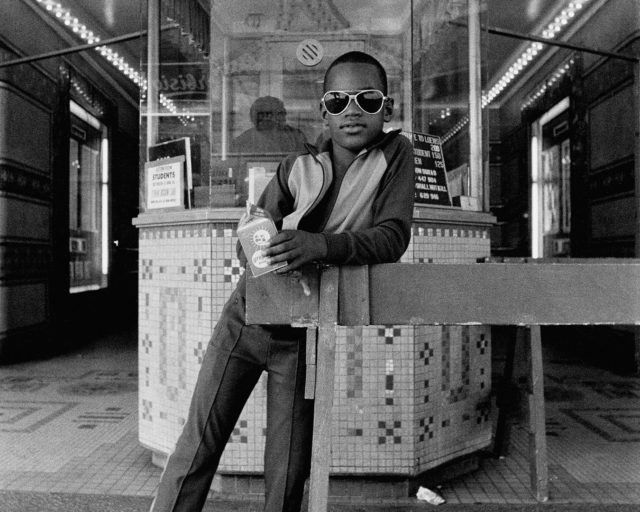

Courtesy the artist

Embser: How would you characterize the changes in the photo world in the decade or so that preceded your arrival at Aperture?

Boot: If you go back a little bit further, I think the major turning point, in terms of how photographers were perceived and how they saw themselves, happened in the wake of Nan Goldin’s Ballad of Sexual Dependency [Aperture, 1986, and 2012]. I think Nan shifted the ground. It was like the old values of reportage—of the detached observer, so to speak—were signaled at an end by Nan and her diaryesque work, her snapshot aesthetic, her relationship with her subjects. So, in the photography scene that I knew, lots of photographers were considering their position, wanting to be appealing in a new landscape that was emerging, where editorial photography was becoming less valuable, while some photographers were being elevated in the art world.

Embser: Appealing to whom?

Boot: Appealing to those who were now defining the market. I’m contrasting a scenario where, for a period, it was what photographers photographed that mattered, changing to one where who they were and their photographic attitude was what mattered. And what mattered to them was that value was placed on their work in the gallery, museum, and among collectors, rather than just in the media. It was a major shift.

But one thing that I felt very strongly about when I came in—I really believed in the idea of the photo community. And I thought Aperture could play a very central role in keeping that community together, and being a place for a community—of picture-makers, collectors, lovers of pictures, academics, everybody who found a sense of belonging in photography.

Embser: Did you feel that during the decade prior to joining Aperture, when you had your own imprint, you were riding the wave of these major changes in photography? That you were being nimble with the way that you were working with photographers and making books?

Boot: One of my maxims when I was running my own imprint was that I wouldn’t do books if the intention of the photographer was to use the book to reposition themselves. I wanted to do books because the work was interesting, full point. I didn’t embark on a book that I didn’t think had something to say to the outside world. Even if it was mainly photography insiders that bought it.

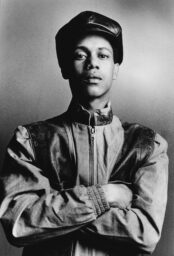

Photograph by Katie Booth

Embser: When you say positioning, do you mean pivoting from photojournalism to the art world?

Boot: Exactly. But somehow, I got a reputation for that, because I’d done a few books with photographers where it did prove to be part of a successful pivot. And I was basically publishing in the area between reportage and contemporary art, what at the time, we called “contemporary documentary.” Lots of 4-by-5 photographs of people posing, rather than pictures caught on the hoof. That was an approach that came out of COLORS magazine more than anything, in my experience, where James Mollison, Stefan Ruiz, Adam Broomberg, and Oliver Chanarin were creating a new photographic approach to social issues, working with large-format cameras, treating their subjects as individuals rather than just as ciphers. Obviously, there were other things going on. It was still quite a regional world, and I saw my job as a publisher to try to add something to the evolving history of photography in Britain.

Embser: It sounds like when you arrived at Aperture, you were prepared for what I would perceive as a kind of “broad church”: there was space for different types of photography, different ways of working. Would you agree with that?

Boot: Absolutely. Although I think the period that I’ve been at Aperture, the values of photography have changed. I mean, we have an active discussion internally at the moment about consent. Is it now a moment where certain kinds of photographs are no longer desirable, or possible, without the explicit consent of their subjects? So, things have always been changing, and they still are. It’s a very dynamic environment, and that’s part of what makes photography so exciting.

Courtesy the artist

Embser: Back in 2011, how did you feel about debates about the possible death of print or the existential future of the photobook or that kind of thing? Did you feel that the moment you arrived was a real crossroads for thinking about the future of photography?

Boot: I thought all along that publishing could be three-dimensional in the sense that it wasn’t only about the book. The book was this tremendous vehicle for a photographer to present their work, communicate their ideas, present it in a context that they shaped. But then there’s what you could do online, and what you could do in the real world in terms of events, and there’s what you could do building community around access to the work, building audience.

Embser: How do you think Aperture compared, around the time of your arrival, with other publishers, such as Steidl or Prestel or Phaidon? What did you think was distinct about Aperture’s books?

Boot: The ’70s were Aperture’s heyday, when we had the field almost to ourselves—there was very little competition in the area, it was a very, very distinct thing that Aperture was doing, that we might now call “classic.” And then by the mid-’80s, all these other publishers were emerging steadily that were much more market-oriented than Aperture. Aperture was always, I think, a little bit productionist. It was about producing the greatest book. They weren’t necessarily the best at getting books into as many people’s hands as possible at that time.

Aperture had a mission statement in the aughts which was to support photography of every stripe. It was about the variety of photography. And Aperture was making a brave go of it in circumstances where there were really strong publishers emerging everywhere, from Scalo to Steidl. It wasn’t like Aperture had disappeared off the scene. It was still there, but it wasn’t leading the field like it used to. And then when I started at Aperture, the question was in the air: What is photography now? Does it matter? Is print dead? Aperture had been debating whether it made sense to continue making books, and whether to go all-digital with the magazine. The economics of publishing was challenged.

We recommitted to photography in print, and then things really fell into focus at Aperture when the “whither photography?” question felt like it was answered. We stopped asking what the new landscape of photography was, because it became apparent. We were getting used to it, and it wasn’t continuing to change.

Embser: What was the “landscape” that settled the question?

Boot: Well, it was a landscape where photography was ubiquitous. Everybody had access to the means of making pictures and publishing pictures. People had become so much more visually literate. Everyone became versed at communicating in pictures. Photography was everybody’s tool to talk about their lives, their world, and be able to get an audience for that. We got used to a world in which the smartphone was central, and where photography was far from undone, but full of energy. Good pictures continued to generate interest in the art market. So the question we became concerned with was more: What was photography best for? What could it achieve? What do we have to contribute to that? I think we addressed that, and distinguished ourselves as a not-for-profit publisher, by adapting our mission to make photography more inclusive.

Embser: To that point, Chris, you have spoken frequently about community. You use the term 3D in thinking about how we might experience photography. And during your time, Aperture, as a space for the photography community in person, was a pillar of the mission. How did you envision Aperture could be a stage for photography to talk about the world? Aperture closed the gallery and bookstore last year, by coincidence only about six weeks before the COVID-19 lockdown forced all galleries and museums to close temporarily. But what was the value of having a physical space in Chelsea that was kind of a meeting point for the photography community in New York and beyond?

Boot: Aperture’s gallery and bookstore on West 27th Street was wonderful. It was an old-fashioned loft and very beautiful, with pillars and beams, and the light was gorgeous. I really miss it! What I tried to do there was make it more of a space for people to encounter each other, to come to new understandings, to be inspired and make connections, more than just a cool space for presenting pictures.

One of the most exciting things that I remember from that period was Daido Moriyama’s Printing Show—TKY in 2011, a three-day project where people bought timed tickets, and there were photographs around the walls and this big central area with photocopiers and binding machines, and Daido was there throughout, working with Aperture interns to reproduce his images. People chose pictures to make up their own versions of what was a book in an edition of, I think, three hundred. Every book was individual, shaped by the tastes and interests of the audience as editors. Each book was physically made by Daido and the Aperture team while you watched, and then he signed each one at the end. It was chaotic, but it was thrilling. It was different from what a white-wall space was typically being used for. How we create a welcoming space in which good things happen became a preoccupation of ours, alongside exquisite publications.

And then there’s what we did in other spaces. Kellie McLaughlin organized these incredible opportunities. Like for the first three years of Paris Photo Los Angeles, we had this fake Italian restaurant on a fake New York street corner, on the Paramount movie lot. It was in the middle of things, and so everyone passed by, and people came to hang out there with us. And you mentioned the stage. One of the most exciting things for me during the time that I’ve been working at Aperture was when we took over Terminal 5 for our Open Road gala, to honor Robert Frank, in 2014. That’s a three-tiered rock-and-roll venue that needed a big sound. We asked Billy Bragg and Alec Soth to go on a road trip to create a show to honor Robert Frank, which they performed on stage. It was ambitious, and it was enormous fun.

Photograph by Madison Voelkel/BFA

Embser: I would say there was a kind of scrappy elegance to the Chelsea space. You might have a workshop for ten students, or you might have Tilda Swinton opening an exhibition, or anything in between, including photocopiers and book-making. There was something about that space that perhaps reflected the broad-church idea that we were discussing about the different channels through which people were coming to photography.

Boot: Yes! I think it was a space with a good heart. We weren’t trying to compete with the museum; we had a different set of opportunities and concerns. We were more free, and wonderful things happened there.

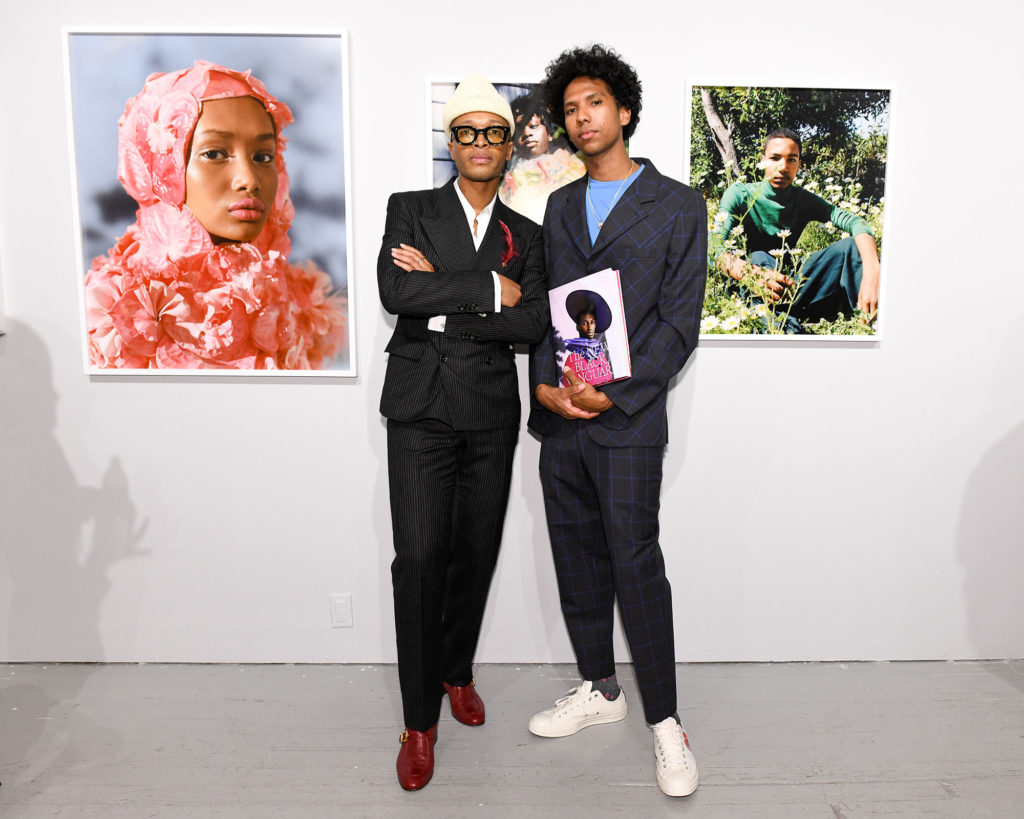

We didn’t have great conditions for vintage prints, so we often stuck pictures on the wall with pins or wallpaper. We started the Summer Open. The model of the typical Summer Open exhibition is kind of conservative. You think of, I don’t know, the Royal Academy’s shows. It’s the most conservative thing on their calendar in terms of the kind of work presented. But we set out to do a more radical Summer Open, with different themes each time. Brendan, you were directly involved in probably the most interesting, certainly the most talked about, of the Summer Opens, which was called The Way We Live Now [2018]. And in that show, one of the guest curators, Antwaun Sargent, rehearsed some the ideas that became The New Black Vanguard, which also features Tyler Mitchell and Jamal Nxedlana.

So we were finding ways to bring people in and, in the process, remold Aperture as much more inclusive. We tried to balance being highly selective, on the one hand—we are a group of editors, if nothing else—at the same time as opening the doors to many new voices.

Photograph by Zach Hilty/BFA

Embser: Shortly after you joined, there was an effort to redesign Aperture magazine and to double down on print. The magazine grew in size. It became more expensive. It became more luxurious. And it became arguably more ambitious—or ambitious in a different way than it had been previously. Was the redesign a response to what we were experiencing with the growth of the digital space, social media, and the disparate ways one might encounter photography in the 2010s?

Boot: The magazine has been different things at different times: different forms, with different values and ideas relevant to their time. When I got to Aperture, it was perceived that print wasn’t the future and that it was going to be increasingly challenged. I didn’t believe that. I was part of an indie photobook-making world that had phenomenal energy, so I saw the appetite for books as growing. It might not have been apparent in the chain bookstore, but there was a movement afoot and incredible innovation going in book-making. And I knew how much photographers needed books. So if we could find a way to pay for them, they were always going to be wanted.

In terms of the magazine, I knew a lot less about magazine publishing when I came in. Economically, it was not in a good place at the time. I mean, like other magazines, circulation was falling. I have to give Melissa Harris, the longtime editor of Aperture, enormous credit because she took it to the peak of its circulation, around twenty-five thousand subscribers, in the ’90s. It had been thematic at one point, but then it became more of a general-interest magazine led by photographers.

When we embarked on rethinking the magazine, our first thought was: let’s make it more about photography. Everybody wants to understand what’s going on. People that we’re connected with, whether they’re photographers or teachers or fans of photography, want to understand the rapidly evolving environment. This was the moment when Michael Famighetti became the magazine’s editor. We needed to do something differently. And we decided that we’d make something bolder, collectible (we hoped), thematic, and more striking and contemporary in its design, a statement.

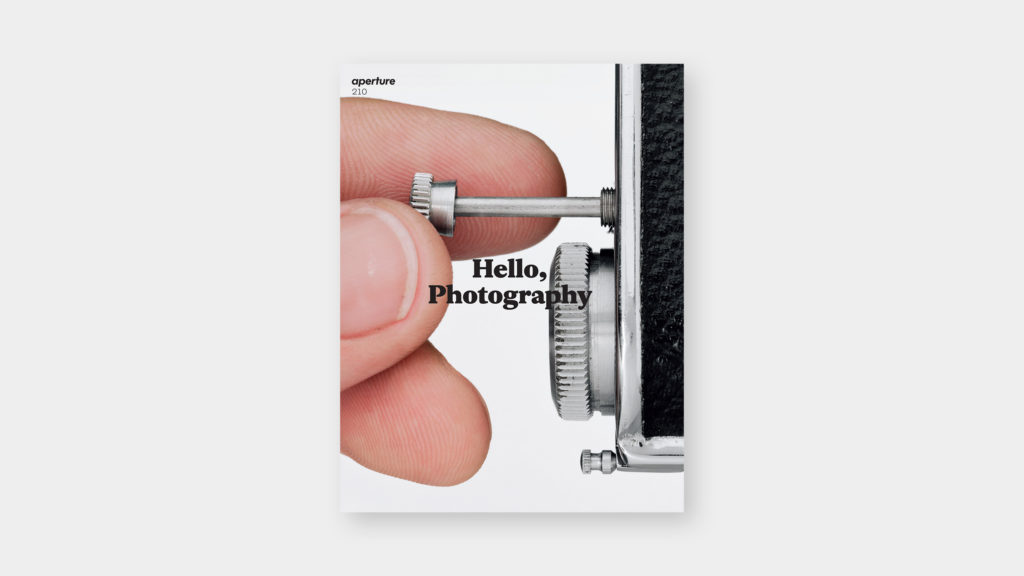

“Hello, Photography” [Spring 2013] was our manifesto for that period, which was an optimistic assertion of the value of photography at a time when a lot of the work being made was—I don’t mean this negatively—kind of navel-gazing. It was ontological about the medium itself. It was the beginning of the “Photography Is Magic” generation— people playing with the possibilities of photography, making three-dimensional objects and thinking about how photography works in physical space, thinking how it works online, as well as in traditional contexts, like a printed book. That moment was very much part of the issue—the first cover of the new design was by Christopher Williams, from a series he’d made about photography—photography about photography. But the issue embraced Garry Winogrand, and the Magnum group’s Postcards from America project, and a breadth of social and visual concerns.

Embser: When you talk about optimism, it was not only the content, in my opinion; it was the physical identity of the publication. I’m trying to imagine being a subscriber in 2013. One season, you get the “old” Aperture, and the next, you get this extraordinary, beautiful, huge, lavish magazine. That is quite a change, and a bullish one.

Boot: Well, we had to change, or we would have died. I think that sense of being on a precipice helped us be fearless, there was nothing to lose! We did the best we could come up with. But it wasn’t an overnight decision. The new direction took many months of thinking, and discussions, before we made the change. It was a risk, because we were doubling the price. We knew we were going to lose people because of the price. We knew we were going to lose people because we had a traditional following who had subscribed for years and years, and who loved Ansel Adams and Dorothea Lange. And we were setting out to be more active in the dialogue about the future of photography.

We did see a loss in readership, initially, but we were able to build that back up, as well as remake the magazine as the center of Aperture, generating content that rolled out online in different forms, in nugget form on Instagram, in online essays and publishing. So the audience grew, but not necessarily for the physical object. And the work of the magazine flowed into new relationships and books and threads of work. But it was all anchored by the physical object, which still, to me, is the most thrilling way to experience work. In print, and as a statement.

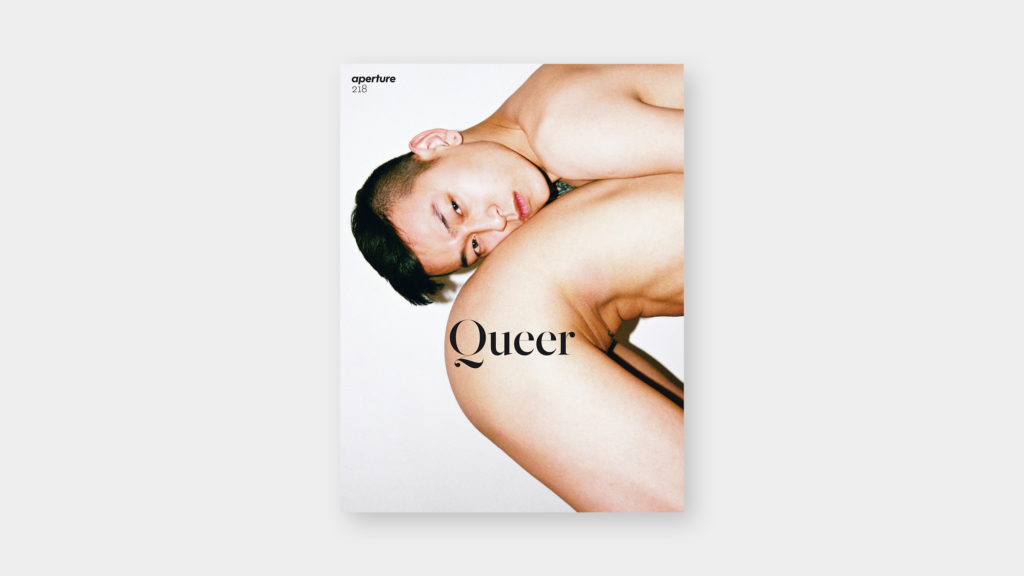

Embser: And things changed again two years later with the “Queer” issue.

Boot: The “Queer” issue [Spring 2015] became, in my mind, very important, because it was very unlike what Aperture had done before. The cover, with Ren Hang’s picture and just the word Queer, was pretty bold. I remember going into a board meeting and showing the cover to our trustees before the issue was published, and saying, “Gird your loins, this is where we’re going!” And they were very supportive. It was the beginning of the magazine taking on these big social topics. We were making a claim for photography’s role in addressing identity and social justice, at the same time as evolving Aperture Foundation’s profile as a more inclusive institution.

Embser: Do you feel that the “Queer” issue—and culturally specific or identity-specific projects generally—informed the larger initiatives of the organization?

Boot: Yes. The “Queer” issue dovetailed with work we were doing on several monographs—of the work of Jimmy DeSana, David Wojnarowicz, George Dureau and, a bit later, Peter Hujar. I hope we were elevating some of the figures from photography’s past. Artists who, post-Stonewall, were moving the language of photography forward. Alongside that, we were elevating contemporary photography and debate about queerness in the magazine.

Embser: I ask that because I wasn’t working at Aperture when the “Queer” issue was published, but I remember getting a copy of it, and my first thought was, Is this going to be it? Like, Aperture did their queer issue, and is this going to be it, one and done?

Boot: It’s interesting you should say that, because when Michael Famighetti approached Sarah Lewis in 2015 about guest editing an issue about the Black American experience, her condition was, “This can’t be all you do.”

I think the magazine serves as a kind of vanguard into new areas and new issues. And I think of a particular magazine issue being successful when it has a long tail of influence, and it leads to book projects, exhibitions, and evolving debates. I love the fact that after the “Native America” issue in fall 2020, we began working on an exhibition for which the magazine itself will serve as a catalogue, even two years after it was first published. And we’re starting to work on several monographs by Native artists as the exhibition tours. That, to me, is a kind of perfect outcome.

Photograph by Katie Booth

Embser: You could say that the “Prison Nation” issue, guest edited by Nicole R. Fleetwood for Spring 2018, was the fullest expression of your “3D” idea of the community.

Boot: For “Prison Nation,” there was the magazine, there was the exhibition, and there was this intense and meaningful set of encounters staged at Aperture’s gallery. We did programs every week for six weeks, most of which included a formerly incarcerated artist or panelist talking about the role of art in rehabilitation. We had lines around the block—photography lovers, but also lawyers and teachers and civil-rights activists. An incredible range of people finding Aperture relevant. That, I think, is where we are at our strongest, where we’re absolutely anchored in the idea of photography as an art, as a vehicle to communicate, but addressing an audience beyond photography. Photography speaking to the world rather than just to photography, and coming to grips with urgent matters of history, and America’s past. Nicole Fleetwood later organized a very successful and impactful show around the same subject at MoMA PS1, which just closed, while we continue to tour an exhibition based on the contents of the “Prison Nation” issue.

Embser: “Vision & Justice,” guest edited by Sarah Lewis, was published in 2016. You have said that this was one of the magazine’s loudest statements, one that reverberates throughout the organization, throughout the photo community, and has informed your own thinking about the idea of “progress.” The launch of that issue at the Ford Foundation in May 2016 was a high watermark for Aperture.

Boot: Sarah Lewis did more than just edit a great issue of the magazine for us. She raised our sights, I would say, and that Ford event took things to another level. It was one of the most exciting photography events I’d ever been to.

Embser: Until that time, Aperture did not have an amazing history of publishing Black artists, so there must have been a kind of catharsis in some way, and also a widening of the tent with the broad exposure of “Vision and Justice” and the sense of inclusivity it projected. And not just for Americans. I remember being on a panel at the Addis Foto Fest in Ethiopia, where a South African photographer, Andrew Tshabangu, said something to the effect of, when he saw the issue, he felt as if he finally belonged. How did the idea for “Vision & Justice” percolate at Aperture, and what has that shift created by the issue meant to you?

Boot: Lots of people were involved. I remember initiating a discussion about Black Lives Matter, and how we as Aperture should respond. Photography was critical to the Black Lives Matter movement, given how images and videos captured on cell phones, to document and describe acts of police violence against Black people, were so central. It also made us question ourselves. We came to the unanimous recognition—across the organization, I would say—that we had inadequately addressed Black experience or elevated the art of Black photographers, and we set out to correct that.

I think “Vision & Justice” was a turning point in our role in the photography world, and our mission, in a way. It altered our mission. And you only have to look at Aperture’s output since then to see what influence it had. “Vision & Justice” also promoted an idea that really affected me, that I’d not encountered before. Sarah Lewis rooted the “Vision & Justice” issue in a lecture of Frederick Douglass’s called “Pictures and Progress,” summarizing that “progress requires pictures because of the images they conjure in our imagination.” That motivated me. It became a thread of Aperture’s work, thinking about photography’s positive role in shaping ideas of who we can be. The “Utopia” issue of the magazine [Winter 2020] is totally a child of “Vision & Justice.”

Photograph by Margarita Corporan

Photograph by Margarita Corporan

This is what photographers were doing anyway. Instagram was having a massive global effect. Pictures were triggers for emancipation. You think about Devin Allen in Baltimore. Or the lesbian and gay movements in sub-Saharan Africa, with activist artists like Zanele Muholi inspiring new possibilities for being. Suddenly, what was happening in New York or Berlin was easily reaching Nairobi and Lagos. And vice versa. People were able to imagine themselves in new ways, which relates to Frederick Douglass’s use of his own visage in the time of slavery, promoting photographs of himself to inspire others’ imaginations for who they might be.

You can hold photography responsible for many bad things in society as well. We have not been particularly focused on that. Right now, photography’s a tool for a kind of commercial surveillance of our tastes and our interests, and there’s a social coercion aspect, so there are perhaps as many arguably negative things going on at the same time. But I think what we did was latch onto this positive role that photography could play in social evolution that motivated many photographers, and reflected where photography was making an impact, and nudged things forward a bit.

Photograph by Roxxe Ireland

Embser: That activating role is arguably quite far from the commitment to photography as a serious art at the beginning of the magazine’s history, and yet it also speaks to this idea of photography’s potential—potentials being a word used in the founding statement in the first issue of Aperture. How have you seen the influence of “Vision & Justice” in other areas of Aperture’s publishing program?

Boot: Well, we’ve published many artists that were featured in that issue. We began relationships with new writers who now work regularly with us. I think, as I said, it inspired an evolution of our mission within Aperture. It helped us develop our understanding of what we could do to make a difference.

Embser: Is there a risk to focusing on social issues in an art and photography magazine? Or is this about building the broad church?

Boot: I remember with the “Future Gender” issue we did in winter 2017, which we invited Zackary Drucker, who’s a transgender artist, to guest edit. I got some, “Are you guys for real?” comments about that. It was the greatest pleasure on my part to say, “Absolutely, yes, it’s for real!” It was fun. It was exciting. It was challenging audiences to think.

Embser: And “Future Gender” remains the third best-selling issue in terms of single copies.

Boot: I’m happy to hear that. It was a very important issue for me. My formative gay experiences were in London in the 1980s. I was in a mixed-race relationship, and my partner, Tony, and I thought of ourselves as pioneering, in a way. But we shared a cultural prejudice, like many gay men, against transgender people. They were often condescended to by those of us who thought we were “real men,” apparently unaware that we were as much in drag as anybody else. It wasn’t until Aperture was working on “Future Gender” that I fully recognized how wrong we were back then.

Embser: Putting the T in LGBT.

Boot: Yes. So, I am very proud we did that issue.

Photograph by Thomas Bollier

Embser: You mentioned the idea of Aperture as a stage, and doing events at Terminal 5. In 2015, Aperture honored Nan Goldin at a gala there. The idea was a live screening of The Ballad of Sexual Dependency slideshow, accompanied by music. I had just joined Aperture two weeks prior, so I was present for that iconic moment, which you have mentioned as an Aperture highlight. What do you remember from that night?

Boot: I want to hear from you first. What did you think?

Embser: Well, what I remember from that presentation was when we got to the part of The Ballad where there’s picture after picture of men, probably gay men, many of whom had likely passed away from AIDS, there was a collective gasp in the audience. It was clearly emotional—the sense that Nan had been there. A lot of people in the room had been in that community, and survived that time, and those who were present felt the loss of their friends painfully. There was both a memorial and a celebratory aspect, and I remember thinking, Wow, this is not like any gala I’ve been to before.

Boot: It’s not like what people expected from a publisher. I mean, that was a great evening. We had a number of musicians who hadn’t worked with each other before when they arrived at the venue on the day. We brought in Samuel Rohrer, this experimental drummer from Berlin, whom Nan wanted, and we had Laurie Anderson, and the folk singer Martha Wainwright, and the Bush Tetras, a punk band who featured in Nan’s pictures. And we asked Pat Irwin—who is brilliant, a real talent—to help orchestrate everything. And then there was this incredible performance, the highlight of which for me—and this was on the first anniversary of Lou Reed’s death, so that sort of echoed in there—was with Laurie on electric violin and Martha Wainwright singing to this plaintiff soundscape by Rohrer, as they did this version of the Velvet Underground’s “Black Angel’s Death Song.” To Nan’s photographs, it was just electrifying. It was so moving and so strong. That was one of my happiest and proudest moments at Aperture, to see that come together and for photographs to be the platform for that.

Embser: One of your other highlights has to do with Hector Xtravaganza. Before “Future Gender” and the “Queer” issue, Nan Goldin informed Aperture and the culture at large about more expansive ideas about family and, specifically, one’s chosen family. In 2018, Aperture published an issue call “Family,” for which we commissioned Stefan Ruiz to photograph one of New York’s greatest families, the House of Xtravaganza. In this case, you were the maestro.

Boot: I approached the House of Xtravaganza (via Grandfather Hector Xtravaganza), one of the most long-standing houses in New York that came out of the ballroom scene. One of the reasons that they were keen on doing that shoot was because we offered to make them a family photo. And it worked out perfectly. It was one of the craziest days in the Aperture space, with about forty members of the Xtravaganza clan. Stefan made a wonderful family picture that became part of their story. And something else happened at Aperture that day. Unbeknownst to me, there was a rift in the family that had gone on for a decade, and this was the first time they’d gotten everybody in the room together. There was a period when we were shooting where they all disappeared into our conference room. We didn’t know what was going on. Later on, Hector told me that—and he attributed it to the atmosphere and the welcome that we’d created for them—they were able to sort out this rift that would otherwise have split them. That happening under our roof—under photography’s roof—speaks to how photography can impact lives way beyond appreciation of art.

Embser: And there was a very moving coda to that story, which is that Hector sadly died a few months after the “Family” issue was published. One of the portraits that Stefan made subsequently ran in the Style section of the New York Times in the memorial essay about him. You gave Hector a parting gift by having such a fabulous and meaningful portrait be the marker, not only at Aperture but in the Times, for the world to see and to know about his life and his passing.

Boot: That’s what it felt like, yes. And it all came out of a great desire to embrace a wider community at Aperture. And Hector deciding to bring his family with him and help us. They danced to Sister Sledge for our Family gala in 2018. And right now, that picture is flying as a flag in Rockefeller Plaza as part of Rockefeller Center’s Flag Project, which I curated this year.

Photograph by Anja Schwarzer

Embser: Chris, you’ve said that there are many photographers for whom it’s the book above all. The book can travel much farther than an exhibition. It can last much longer. It’s a work of art in its own right. You’ve said many times that a book can change an artist’s life and represent their legacy. And you talk about the relation of Aperture magazine to the books, and the role of the book as an anchor for elevating the ideas or point of view of a photographer. But what about the books themselves? Aperture has published about 150 new books in the last ten years. Can you name a few that, for you, are the most memorable?

Boot: One of the things that has been so rewarding at Aperture is working with a team of great editors, all driven by a conviction for each book they bring to the table, to make it with love and energy. Each editor has their own personality, a particular relationship to photography, particular taste and knowledge, and a sense of how a book can work, which defines each of their books. At the same time, all the editors are supportive of each other. For the most part, we have decided together which books to do, with a team spirit.

Let me think of something by each editor that stands out for me. Brendan, in your case, I guess it would be Deana Lawson: An Aperture Monograph [2018]. It’s such a beautiful book that you pursued with remarkable clarity and determination! I won’t forget that small launch gathering we did with Deana at Sikkema Jenkins, where Deana was in tears, talking about how this was the book that she wished she’d had as a fifteen-year-old girl, in terms of the regal respect it plays to Black women. That was incredibly moving.

I’ll treasure The Difficulties of Nonsense [2016], Robert Cumming’s book that Amelia Lang edited. It wasn’t as successful as it should have been; it’s great work, Cumming should be better known. I would include Kwame Brathwaite’s Black Is Beautiful [2019], which Michael Famighetti edited, that tells a story of art and fashion and activism, and which evolved out of the “Elements of Style” [Fall 2017] issue of the magazine and a thread of projects about photography and the idea of beauty. It was so rewarding to honor Kwame, alongside Inez & Vinoodh and Zackary Drucker at our Elements of Style gala in 2017, and to establish Kwame firmly into the story of art and photography, where he belongs.

A major chapter in the thread of our thinking about beauty is The New Black Vanguard [2019], which Lesley Martin edited with Antwaun Sargent. It’s a great example of a book driven by a vision, and a mission—the editors’, Aperture’s, and the photographers’—that’s historically and socially important in terms of giving shape and voice to a movement and, at the same time, overflowing with the pleasure of photography. It was a great publishing moment for Aperture.

Lesley Martin and Denise Wolff have been such prolific editors; I think I have to pick two books for each! I guess for Lesley, I’d also pick The Chinese Photobook: From the 1900s to the Present [2015], which was a Herculean project and tells a story about China that I learned so much from, as well a really important contribution to knowledge about the story of the photobook, in a line of work we’ve done about asserting the centrality of the book to the evolution of photography.

For Denise Wolff, I’d also have to pick the new limited-edition pop-up Houseplants by Daniel Gordon [2020]. It’s so inventive, and it lifts your spirits! And I’d single out The Open Road [2014], which she conceived and developed, that has this great design by Sonya Dyakova, and was perhaps the first project in my time where the whole Aperture machine started working with all its cogs in sync, with the book as the anchor for storytelling across multiple platforms and events.

Among Melissa Harris’s books, the new edition of David Wojnarowicz’s Brush Fires in the Social Landscape [2015], an update of the magazine issue of the same title published twenty years earlier, conjured Wojnarowicz in a way that is so strong, and so uniquely expressive of Melissa’s editorial personality. I didn’t have the opportunity to do many books myself while at Aperture, but I had the pleasure of realizing George Dureau: The Photographs [2016]—in the same line of recuperating transgressive queer artists whose photography took shape after Stonewall.

I don’t think I am doing my colleagues justice here, nor the great authors and artists we’ve had the pleasure of working with, such as Marvin Heiferman, Penelope Umbrico, LaToya Ruby Frazier, Stephen Shore, Zanele Muholi, Richard Misrach . . . there are so many.

Photograph by Zach Hilty/BFA

Embser: You’ve sometimes called Aperture “a museum turned upside down.” What do you mean by that?

Boot: Typically, a museum creates an exhibition, while publishing a catalogue to support it. We work the other way around. We publish books that you don’t need to see the related exhibition to make sense of. They’re experiences in their own right. They’re objects of beauty as well as vessels for an idea or a point of view. Where a museum puts the exhibition first, we put the book first. While we are creating the book, we start thinking about the opportunities a book presents for the artist, for the work, for exhibitions and events, and across other channels. They are all held together by the book. And I think, without that physical form, everything is sort of ephemeral. The physical form of the book is a statement that lasts forever, even if a book is only printed in a thousand copies. It’s permanent. We give life to the work, with the book at the heart of it.

Embser: Are you pleased with what you’ve been able to achieve at Aperture over the last decade?

Boot: Yes, very much so. It’s been the biggest and most consequential job of my life, and I feel happy about leaving Aperture strong, in great shape, clear about its purpose, and doing its best work. I am looking forward to seeing the new directions that Aperture will take under Sarah Meister’s leadership, and personally wish her the best of luck. I hope she has an experience with Aperture as rewarding as mine.