Promised Lands

Are Israel and the West Bank an oasis, homeland, or colonial state? Twelve photographers set out to describe a contested territory.

Jeff Wall, Daybreak, 2011. Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery

This Place, an exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum conceived by photographer Frédéric Brenner, opens with a monumental tableau by Jeff Wall. Daybreak (2011) restages a happenstance encounter with vividly garbed bedouin olive pickers, found sleeping on the ground near a prison in the Negev. Typically, for Wall, the scene juxtaposes the immediacy of documentary with the precision of cinematic postproduction. In spite of its artifice—Wall used a team of assistants over the course of several weeks to make the image—Daybreak isolates the uncanny moments and parallax of vision that This Place seeks to draw into view.

Frédéric Brenner, The Aslan Levi Family, 2012. Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York © the artist

The exhibition is an elaboration of a long-term project through which Brenner has charted the global Jewish diaspora—often by way of staged family portraiture that calls to mind both August Sander and Tina Barney. Brenner’s own work is included here, but complemented by and resituated amidst the projects of the eleven other photographers he invited to immerse themselves in Israel and the West Bank between 2009 and 2012. Recognizing the contested realities of quotidian life there, his ambition was to enact “une parole poétique,” attempting to transcend the stale binaries through which this landscape is often figured. Such a “poetic” approach risks a retreat into sentimentality, eliding the high stakes of a land inscribed by seemingly intractable conflict. But, taken as a whole, the discrete practices brought together in This Place are more than the sum of their parts: the resulting six hundred photographs on display produce a humane and at times revelatory counterarchive of a place known, by turns, as an oasis, a homeland, a colonial state, or a utopian site of return.

Martin Kollar, Untitled, from the series Field Trip, 2009–11. Courtesy the artist

With its telescoping levels of magnification, and its emphasis on the taxonomic or seemingly banal environments, This Place might trace its conceptual roots to the landmark 1975–76 exhibition New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape, at the George Eastman House. There are, in fact, overlaps in personnel from that earlier project, such as Stephen Shore and Thomas Struth. In This Place, Shore provides a suite of majestic desert landscapes. Struth contributes large-scale inkjet prints that oscillate between moody interiors, vernacular architecture, and crisp family portraiture; his Basilica of the Annunciation, Nazareth (2014) is at once hauntingly intimate and disconcertingly inert. The aesthetic virtuosity of such photographs might, as standalone images, either distance or romanticize contemporary Israel, but in the context of the exhibition’s larger framework, they underscore the ways in which the same topographies and streetscapes can be filtered or repurposed—say from Shore’s sublime promontories, or under Struth’s clinical scrutiny.

Fazal Sheikh, Desert Bloom 2, 2011 © Fazal Sheikh. Courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York

In a more explicitly conceptual register, Fazal Sheikh reprises the surveillance investigations of Ed Ruscha and Robert Smithson, strafing the open desert for signs of life. Desert Bloom (2015) is the most subtle and textually reliant work on display, comprising a large grid of beige imagery—denuded landscapes bearing scars of human intervention. Sheikh provides a brochure describing the coordinates of each photograph and detailed field notes researched upon return from his travels. The approach is systematic but not deadpan, and parlays the colonial logic of the aerial survey into a sustained psychogeographic history of seemingly “empty” space.

Gilles Peress, Contact Sheet, Palestinian Jerusalem, 2013. Installation view, detail © the artist

Throughout the exhibition, sustained looking on the part of both the photographer and viewer is counterbalanced with more documentary immediacy. For instance, for This Is Where I Live (2012–15), Wendy Ewald put the camera in the hands of constituencies—urbanites and villagers, children and elders—reproducing dozens of the results at roughly 5 by 7 inches. Ewald’s project is sociologically complex and politically audacious, but, like Gilles Peress’s grid of medium-scale street scenes in Palestinian Jerusalem (2013)—handheld, off-kilter shots that capture a cosmopolitan bustle—it lends itself less to museum viewing than to a more asynchronous, digital interface. Still, Ewald and Peress draw into sharp relief the subtle boundary between the archive as framework and as formal structure.

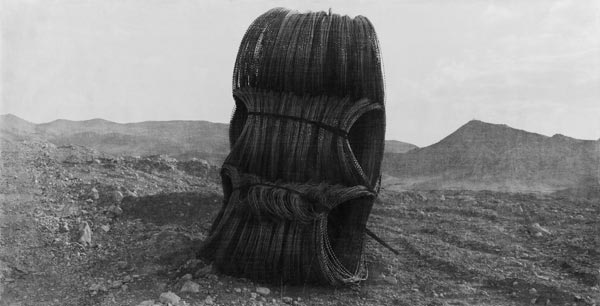

Jungjin Lee, Unnamed Road 083, 2011 © the artist

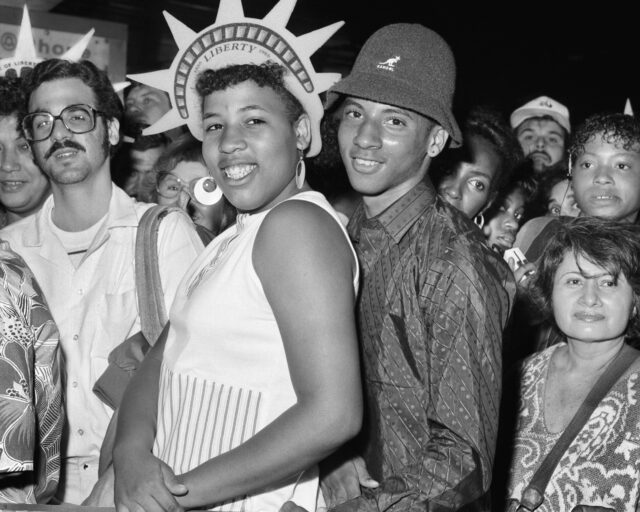

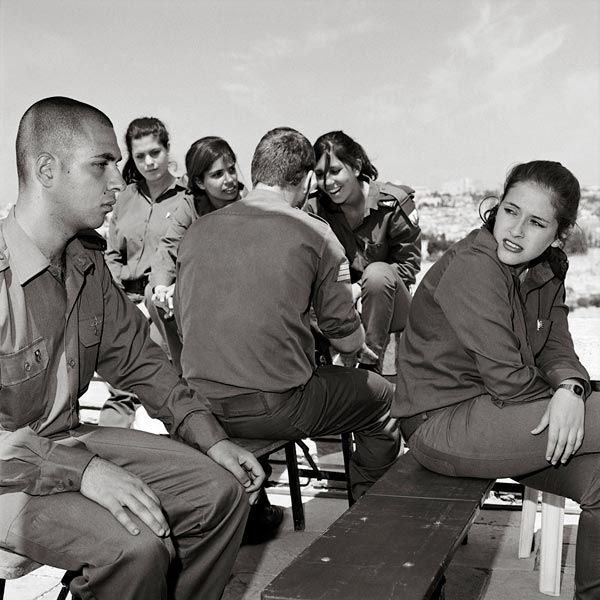

Such taxonomic intensity is, in turn, complemented by moments of old-school formalism and blunt humanism. Jungjin Lee’s panoramic registration of natural forms on handmade paper is gauzy and surreal, bearing uncanny traces, like latter-day rayograms. Celebrated Czech photographer Josef Koudelka frames the bleak surfaces of the partition wall being built by Israelis in the West Bank, which in high-contrast black and white evokes the carceral realities of his youth in Eastern Europe. Koudelka’s works literally partition the exhibition—the wide expanse of his panoramic shot is displayed faceup on an elongated wall in miniature. And THEM (2010–11), Rosalind Fox Solomon’s square format series, hearkens to a bygone golden age of street photography. Unabashedly lyrical and intimate, Solomon’s images would not be out of place in the great midcentury photography exhibitions organized by Edward Steichen or John Szarkowski.

Rosalind Fox Solomon, Jerusalem, 2011 © the artist

In many ways, Brenner’s project is of a piece with such vintage curatorial modes, which prioritized modernist finish and a roseate universalism, but also with the later work of Allan Sekula, who merged metaphor and unflinching realism. This Place is aware of the confounding nuance and high stakes of representing even the most banal scenes of everyday life in Israel and the West Bank, but the exhibition makes a confident claim for the capacity of art to address public debates in ways that photojournalism cannot. The danger, as curator T. Z. Toukan has noted, is in aestheticizing rather than confronting the complexity of this contested terrain. Speaking of art in Palestine in 2010, he wondered, “Does trauma—presented in an art context—become aesthetically appealing, telegenic so to speak, and, if so, can the telegenic aspect be a productive thing?” This Place, a compelling and dissonant experiment, leaves that question unanswered.

Ian Bourland, a historian of photography and critic of the global contemporary, is an assistant professor at the Maryland Institute College of Art.

This Place, curated by Charlotte Cotton, is on view at the Brooklyn Museum through June 5, 2016.