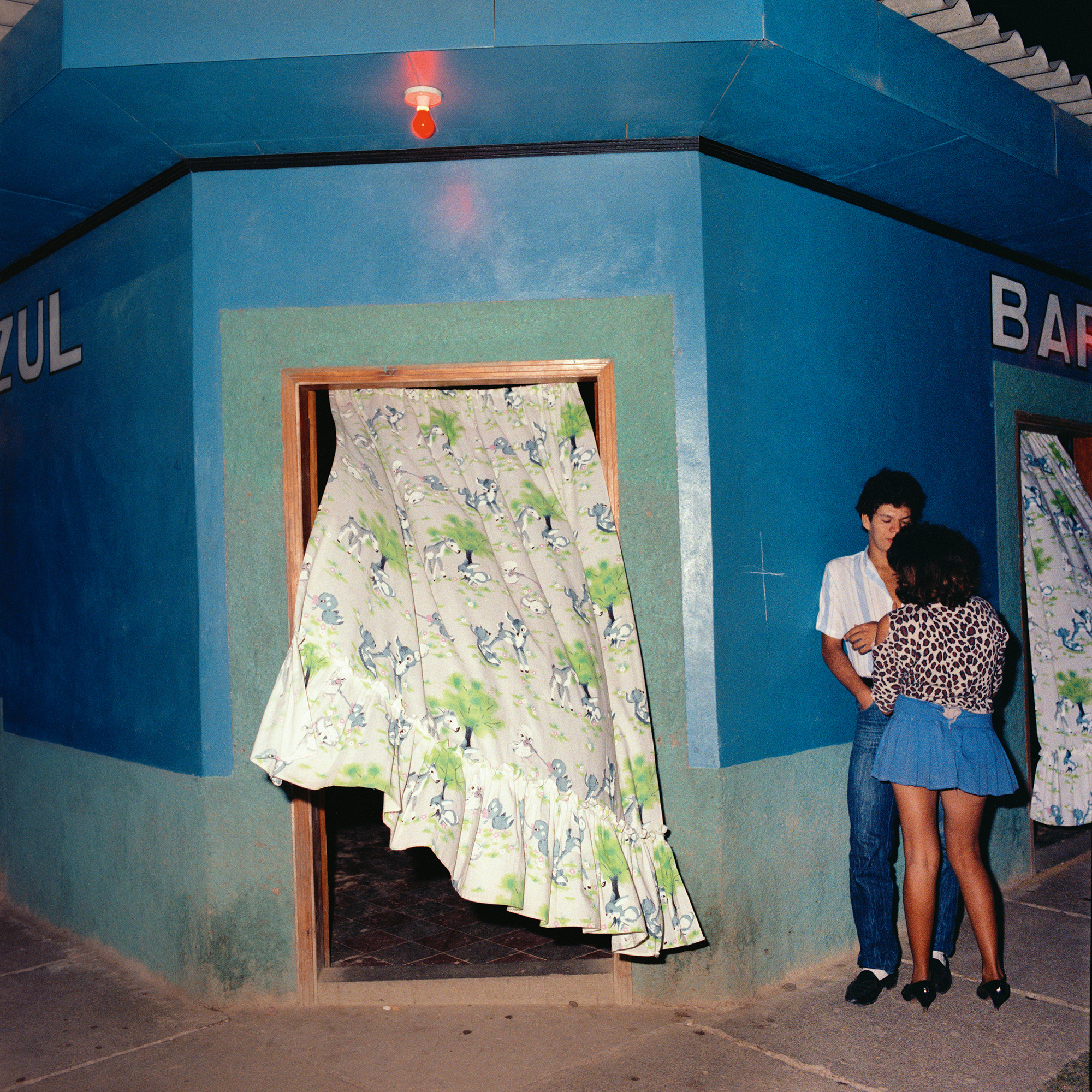

Rafael Goldchain, Nocturnal Encounter, Comayagua, Honduras, 1987

Over the last decade, the Art Gallery of Ontario embarked on an initiative to incorporate twentieth-century photography detailing life in Argentina, Chile, Nicaragua, Honduras, Guatemala, El Salvador, and Mexico into its collections. Beyond poetic images created by Graciela Iturbide and Manuel Álvarez Bravo, the Toronto museum also houses photographs of protests and coups. Such grim subjects might be expected in a Latin American collection: during the latter half of the century, the region was convulsed by civil wars, a genocide, dictatorship, and murderous US intervention.

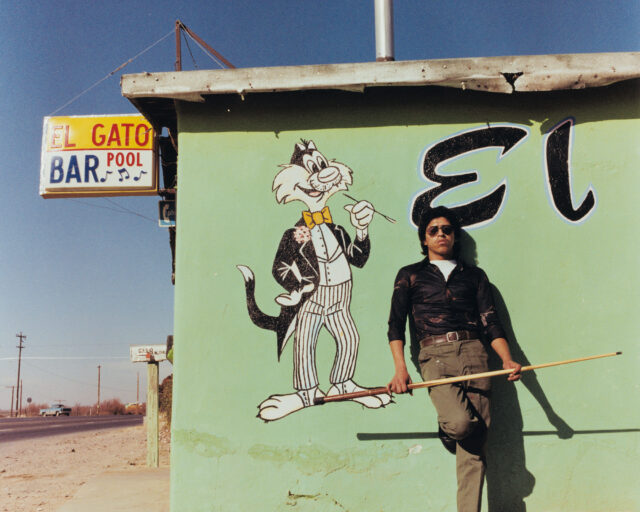

One recent acquisition provides an unexpected twist: lushly colored images by Rafael Goldchain, a Chilean-born photographer of Polish Jewish heritage, who settled in Toronto in the 1970s and in the mid-1980s traveled on a grant to Mexico and Central America. There, he took pictures of residents who struggled on the sidelines of the Guatemalan civil war, CIA interference in Honduras, and Nicaragua’s revolution. Yet instead of focusing on conflict’s “decisive moments,” Goldchain showed lyrical glimpses of people’s desire, grief, repose, and piety.

Such is the case in A Young Man’s Grave, Nicaragua (1986), which reveals a collage adorning a final resting place. The artwork frames a studio portrait of the deceased, a wide-eyed, thinly mustachioed stripling surrounded by dried flowers, clouds, and angels. The offering is saturated with intense blues. “I was in a cemetery in Matagalpa,” Goldchain told me recently, mentioning the city in west-central Nicaragua involved in the Iran–Contra conflict. “Had this young man fallen as part of that? I didn’t know. I had heard that there was a tradition where children who pass away automatically become angels. This boy was of the age that he could be both, a soldier and an angel.”

Goldchain’s ability to freeze tender, ambiguous moments against the backdrop of political violence constitutes a distinct kind of conflict photography. The 1980s “were the era of Susan Sontag and the whole Goya perception of pain,” AGO curator Marina Dumont-Gauthier explained. She referenced Sontag’s On Photography (1977), which inveighs against the power of war images to anesthetize viewers to suffering. “What Rafael is offering is so different,” she said. According to Dumont-Gauthier, back when Goldchain photographed his images, people were not ready to view complex and polysemous images of war “because it somehow felt disingenuous.” She thinks the time is now ripe for Goldchain’s approach. “The pain is still there. Once the war is over, these stories continue.”

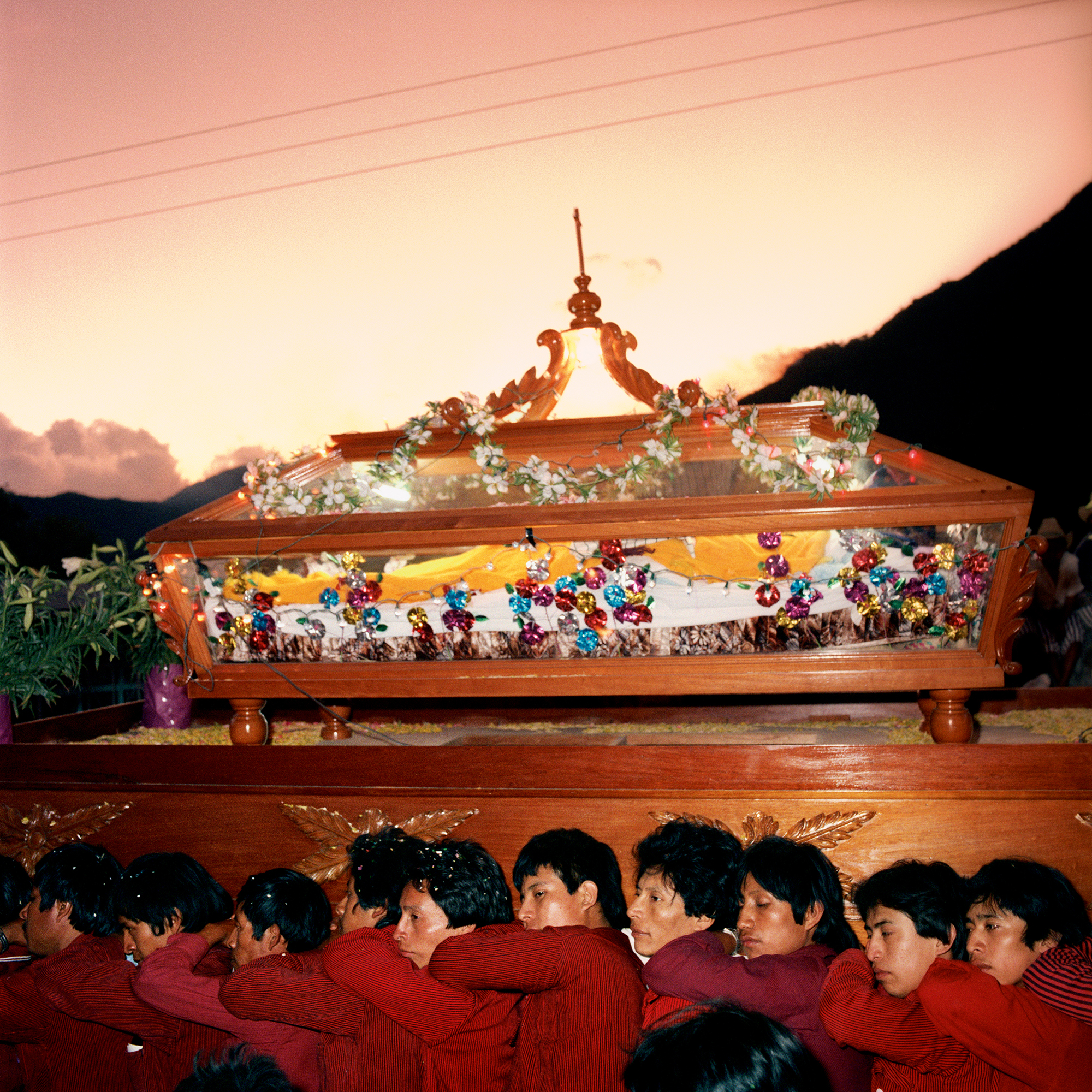

Goldchain presents the continuing story in works such as Easter Procession, Santiago Atitlán, Guatemala (1986). Depicting ten men carrying a tinseled casket that appears to contain a statue of Jesus Christ in the tradition of Santa Semana, the picture achieves a forward propulsion amplified by the undulating line created by the heads and shoulders of the pallbearers. The image’s mingling of beauty and mourning is complicated by the fact that four years after it was taken, army soldiers would open fire on an unarmed crowd of Tz’utujil Mayans in Santiago Atitlán as part of the atrocities that punctuated the country’s civil war.

“I wasn’t a war photographer,” Goldchain told me. “I sometimes took photos of bullets in walls, semi-destroyed ruins, but those pictures didn’t have any of the complexity that I was after. And I didn’t want a bullet in the heart either. My work is more elliptical.”

Goldchain’s allusive impulses led to Nocturnal Encounter, Comayagua, Honduras (1987), which initially reads like a snapshot of carefree lovers. A man wearing a striped blue shirt smiles down at a dark-haired woman who sways her hips. The innocent-looking assignation takes place in a turquoise-and-cerulean alleyway. But knowledge of the political context introduces menacing undertones of male dominance to the photograph. “During the Iran–Contra affair, there was a very large air base in Honduras called Palmerola. There were a lot of bars where American soldiers met lovely Honduran girls. This is a red-light district, a meat market.”

“Rafael’s work allows people to engage with photography that tells a fuller story,” Dumont-Gauthier said, an affirmation of Goldchain’s Mexican and Central American images that resonates with the recent institutional validation of Latinx photographers, such as Louis Carlos Bernal and Paz Errázuriz, who breathed new life into the documentary tradition in the 1970s and 1980s. The curator also noted Goldchain’s deliberate use of color, suggesting that “Blue is associated with nostalgia. The colors help us process our own emotions. If the photo were against a red backdrop, it would have a completely different meaning.”

All images courtesy the artist

Goldchain’s associative palette perhaps finds its deepest expression in A Tehuantepec Maiden, Juchitán, Oaxaca, México (1986), where a girl wearing a huipil stitched with crimson-and-pink florals stands against a mural of the Virgin of Guadalupe. As in A Young Man’s Grave, Nicaragua, a painted sky forms the backdrop. The jaunty artificial flowers in the girl’s hair contrast with her stoic expression. Does her steadfast look telegraph the larger struggle of armed forces disappearing and murdering Oaxacan dissidents during this era? The girl’s gaze seems almost unnervingly grave in light of that history.

“She was fifteen years old,” Goldchain recalled, nodding his head contemplatively. “When I first showed these photos, people said I was noncommittal and too artistic and aesthetic. But I could only be who I could be.”

This article originally appeared in Aperture no. 256, “Arrhythmic Mythic Ra,” guest edited by Deana Lawson.