On Record: RoseLee Goldberg and Roxana Marcoci in Conversation

In this excerpt from the upcoming Aperture magazine, Winter 2015, “Performance,” MoMA’s Roxana Marcoci and Performa’s RoseLee Goldberg examine these questions. This article also appears in Issue 19 of Aperture Photography App.

Yves Klein, Leap Into the Void, 1960 © Yves Klein/ Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York/ ADAGP, Paris 2015/ The Metropolitan Museum of Art and courtesy Art Resource, New York

Roxana Marcoci: RoseLee, you pioneered the study of performance art with a landmark book, Performance Art: From Futurism to the Present (1979), and recently expanded it with an account of the technological, political, and aesthetic shifts in performance art that have occurred since the turn of the new millennium. What do you think the advent of photography did for performance? And why have photography and performance been so intricately linked? From its beginnings, photography has had a unique relationship to performance, which explains why we can chart a history of modern and contemporary performance art, while it’s more difficult to do so for premodern times.

RoseLee Goldberg: A fascinating place to begin, “the advent of photography.” Before the photograph, a painting or drawing would have captured the performances taking place in the studio or workshop—sometimes even those staged with an audience present, but more often done without a public. We need to activate our imagination to conjure the models and backdrops used to make so many of the great history and narrative paintings from the past. Performance since the 1960s became associated with the word documentation, as though the photograph was simply a record of an act, an afterthought, to capture an ephemeral event. But as we know from images of works by Yves Klein, Joseph Beuys, Yoko Ono, Carolee Schneemann, or Chris Burden, and so many artists of the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s, photographs of performances were often consciously staged for the camera, allowing them to become iconic and powerful images that would live on into the future.

Rineke Dijkstra, Kolobrzeg, Poland, July 23, 1992. Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery

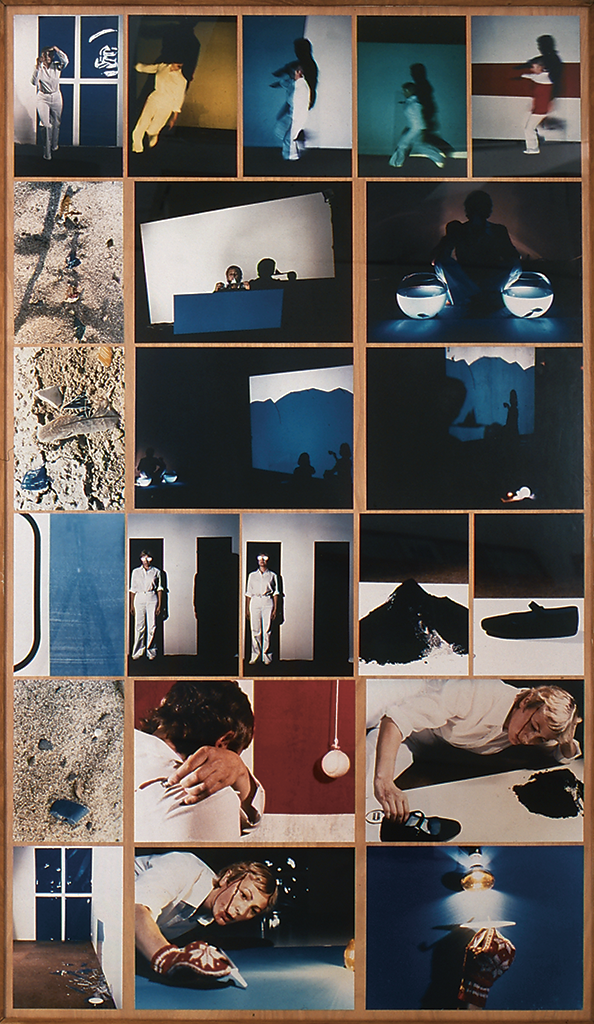

RM: Gina Pane, a pioneer of performance art, from the start collaboratively worked with one photographer, Françoise Masson. In discussions with Masson, she prestaged the shots that the photographer then took during the live performance. Pane made the final selection of pictures and composed them into montages that she called constants d’action (proofs of action). Photography, beginning in the 1960s, signaled a critical change in its relationship to the discourses of performance, sculpture, writing, and film, as artists who did not consider themselves photographers in the conventional sense began to use the camera for projects that were not specifically photographic. This moment also coincided with the advent of Conceptual art. Performances are ephemeral; photographs are permanent. When is an image more than a mere document? How do images bring us closer to an event we never witnessed?

Gina Pane, Little Journey, 1978. Photographs by Françoise Masson Collection Frac Bretagne/ © ADAGP, Paris 2015

RLG: The anti-aesthetic of Conceptual art and performance, so-called documentation consisting mostly of black-and-white photographs drained of spectacle or framing, or carefully monitored lighting, was the beginning of the break—the separation of what we consider photography in its historical and conventional sense, and the photograph as created by visual artists of the 1970s and ’80s. Over the past fifty or so years there has been an incredibly rich history of performances made with the intention of being captured by the camera, or vice versa, photographs made of unforgettable performances, as you made so clear in your important 2011 exhibition, Staging Action: Performance in Photography since 1960, at the Museum of Modern Art. Roxana, as a curator and historian looking at photography in so many forms, what do you think distinguishes photographs of performance by visual artists? To me, it seems that no photographer could possibly come up with an image such as Marina Abramovic’s Balkan Baroque (1997), of her scrubbing 1,500 cow bones, wearing a white tunic that becomes gradually bloodied over time. It represents the horrors of ethnic cleansing in a way that is particular to a visual artist. A photojournalist or photographer might make the image far too literal; it would have none of its poetry. There is a formality to Marina’s photograph—and a visual imagination at work in interpreting its content—that would simply not come from a photographer. For me, photographs of performances reinforce that these performances are the work of visual artists. Consciously or not, the artist understands the visual impact of her performance, so no matter who is photographing the work, whether staged or captured live, by the artist or by an independent photographer, the content, the image that emerges from the performance, could only come from this genre we call artists’ performance.

Marina Abramović, Balkan Baroque, Performance, 4 days 6 Hours, XLVII Biennale Venice, June 1997 © Marina Abramović and courtesy the Marina Abramović Archives, Sean Kelly Gallery, New York, and Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

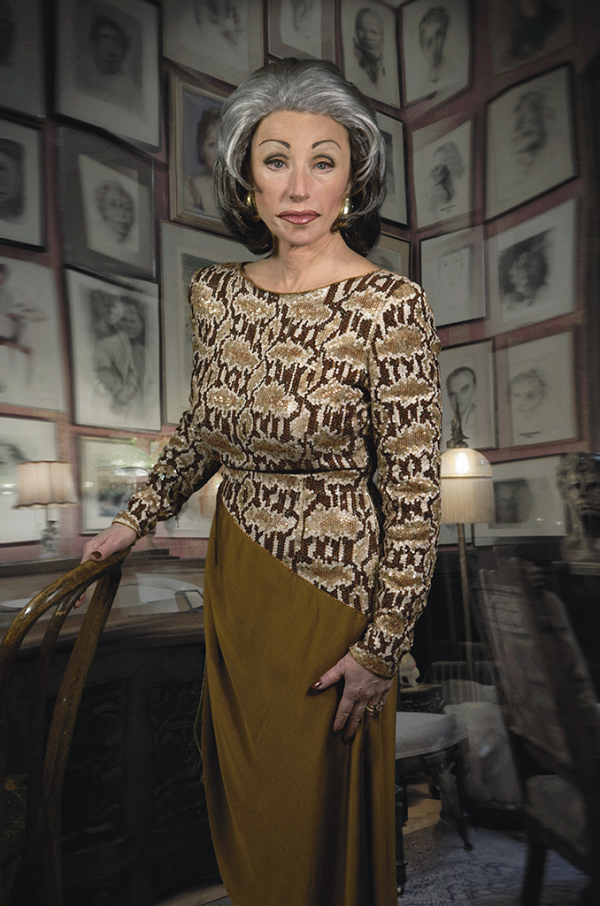

RM: The premise of Staging Action: Performance in Photography since 1960, and prior to it the section that focused on “The Performing Body as Sculptural Object” in the exhibition The Original Copy: Photography of Sculpture, 1839 to Today, which I curated at MoMA in 2010, was that photography plays a constitutive rather than merely documentary role when performance is staged expressly for the camera. The photograph of an event constitutes the performance as such. Artists working in front of and behind the camera—Bas Jan Ader, Eleanor Antin, Chris Burden, VALIE EXPORT, Gilbert & George, Yves Klein, Lynn Hershman Leeson, Ana Mendieta, Bruce Nauman, and Lorna Simpson—have engaged the “rhetoric of the pose,” a pose enacted for and mediated through the camera lens. Especially in the radicalized climate of the 1970s, when women’s liberation took center stage, artists such as Hannah Wilke reconfigured their bodies in the spirit of activism to comment on the power structure of gender difference. And they used performance and the camera to engender it. To make what she called “performalist self-portraits,” such as S.O.S. – Starification Object Series (1974–82), Wilke hired a commercial photographer to take pictures of her posed like a fashion mannequin in various states of undress, sporting here an Arab headdress, there sunglasses and a cowboy hat, there curlers in her hair. She also “scarred” her naked flesh with a swarm of labia-shaped chewing-gum pieces. Wilke’s pose as a stigmatized star in S.O.S. underscores the key role of the camera in the intersection of performance and photography. My question, then, is whether there is such a thing as unmediated performance.

RLG: Depends on how strictly you define mediated. As already mentioned, painting and drawing before the twentieth century, as well as text, word of mouth, are all forms of mediation.

RM: What would you say, then, about the work of Tino Sehgal, who insistently resists any kind of documentation of his time-based work?

RLG: Indeed, I cannot think of any performance today that is unmediated or not photographed, except for the work of Tino Sehgal, who, as you point out, has emphatically resisted documentation. Yet his position is as much a formal proposition as one of denial, which suggests that his concepts are more fully absorbed by those who watch and listen, and who are not distracted from their engagement with the performance by a camera or an iPhone in hand. In some ways, his refusal to allow photography works in favor of such submission to the work itself. It also forces writers to examine the work quite differently, filling in for the missing images. It’s important to remember that Tino’s starting point is dance—the transference of ideas, of body shapes, content that moves along a different trajectory, in muscle memory—and I believe he’s asking us to give his work that level of visceral and intellectual concentration.

RM: A year ago I organized a forum on contemporary photography at MoMA around the Pier 18 exhibition organized in 1971 by independent curator, activist, and publisher Willoughby Sharp. Sharp commissioned twenty-seven artists—all male, ranging from Acconci to Lawrence Weiner—to engage in performative actions on the pier. Realizing that the derelict structure could not accommodate an audience, Sharp envisioned the end result of the commission as a museum presentation, giving the photographic duo Harry Shunk and János Kender, who documented the performances, an integral role. Pier 18 foregrounds the degree to which photography actively contributed to the conceptual makeup of performance art in the 1970s. I invited Barbara Clausen, who teaches performance theory and history at the University of Québec, to be one of the guest speakers at this forum. She argued that what we perceive as “live” performance is always subject to mediation, since each performance is already built on the relationship between mediated and so-called authentic identities. Consider TV Bra for Living Sculpture (1969) or Concerto for TV Cello and Videotapes (1971), for instance, in which experimental cellist and performer Charlotte Moorman integrates live with mediated elements in performing Nam June Paik’s scores. I think she has a point. How do you see the photograph mediating the experience of the viewer?

Mike Kelley, Extracurricular Activity Projective Reconstruction #32, Plus, a Performa commission, 2009. Photograph by Paula Court and courtesy Performa

RLG: The photograph for me is like picking up a shard of pottery in Pompeii and finding the story of an entire civilization in a handful of material. The photographer is the first tier of the history of performance, the first line of record, and we need to learn how to read the photograph—as good art historians or archaeologists do—for its iconography, for its clues about the times, the politics, the communities in which the work took place, where it occurred: Were people seated on the floor or standing? Does this photographer give us a sense of audience, or not? The more we study the photographs of a performance from the past, the more details are revealed. Photographs give us back our experience of life. We see our own histories through childhood photographs and think that we actually remember the moment even if we were too young at the time to have registered the memory. So, yes, I think photographs have an extraordinary capacity to bring us closer to the work, to give us an experience of the work, and to allow us to build a reference bank of images and ideas as we move on to the next performance, whether witnessed live or not. They make our understanding of the world and of the values and sensibilities of the artists making this work more layered, more sophisticated, more complicated