Redux: Italo Calvino's "The Adventure of a Photographer"

Italo Calvino, the Italian writer, began his tribute to Roland Barthes in La Repubblica with a horrific image of defacement. Barthes, Calvino noted, had been disfigured beyond recognition by the accident that had killed him on February 25, 1980, lying unidentified for hours in the hospital. This reminded Calvino of the book that he was reading only a few weeks before its author’s death: La Chambre Claire, or Camera Lucida, as it is better known today. Sitting down to write the tribute in April 1980, Calvino was struck by how Camera Lucida was more a book about love and death than about photography. It made him think of Barthes lying dead, “name unknown,” in Salpêtrière, “the frail and anguished link with his own features . . . suddenly torn as one tears up a photograph.”

Most of us find it strangely difficult to tear up a photograph, even when it is of an inanimate object, a landscape, or someone we do not know. We find ourselves stopping short of the imagined violence of the act, finding it much easier to tear up, say, a letter. The flea markets of Europe, as Tacita Dean discovered while making Floh (2001), are full of photographs that have been abandoned rather than destroyed. Yet, the tearing up of photographs as an extreme gesture that fuses madness and violence forms the climax of a story written by Calvino in the mid-1950s. It is called “The Adventure of a Photographer” and became part of Difficult Loves, a collection of finely reflective short stories, or “adventures,” each involving a different figure: a poet, a reader, a traveler, a soldier. Written more than two decades before Camera Lucida and Susan Sontag’s On Photography, Calvino’s “The Adventure of a Photographer” reads, to me, like a far more contemporary parable about the medium than those canonical texts by the Sontag-Barthes-Benjamin trinity that remain mandatory for serious photographers or writers on photography today.

Calvino’s photographer, Antonino, is a “hunter of the unattainable.” Initially reluctant to pick up the camera his friends use so avidly, Antonino’s relationship with photography starts as a pursuit of “life as it flees,” but soon turns into a “passion difficult to put up with”—a state of isolation caught between obsessiveness and a pervasive sense of loss; everything that is not photographed is lost. Antonino realizes very quickly that what lurks in his “black instrument” is nothing but a kind of madness. This madness is a forking path. One path beckons outward, toward the doomed and impossible desire to document everything that exists and happens before it is lost forever. The camera must record all reality, all history; only then would it begin making some sort of crazy sense. The other one leads inexorably within, into the labyrinths from which the eyes, windows of the soul, look at the world outside. Yet, in his studio, as the photographer focuses the camera on his model, her body forced into a sequence of grotesque poses, the two roads, inner and outer, seem to cross again “in the glass rectangle.” It is “like a dream, when a presence coming from the depth of memory advances, is recognized, and then suddenly is transformed into something unexpected, something that even before the transformation is already frightening, because there’s no telling what it might be transformed into.” “Did he want to photograph dreams?” the half-mad photographer asks himself, and the suspicion strikes him dumb.

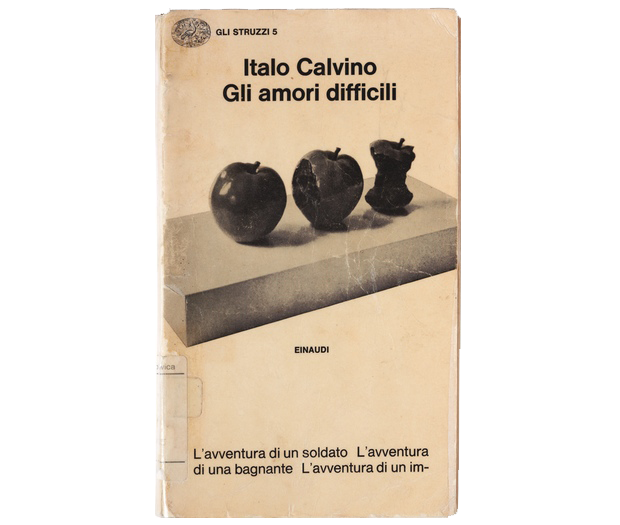

Italo Calvino, Gli amori difficili (Difficult Loves) (Einaudi, 1970). Courtesy Fondazioni Luigi Einaudi, Turin.

In recording Antonino’s descent into a psycho-pathology of everyday life driven by the camera, Calvino shows how photography could lead, through an obsession with capturing the real, toward the unhinging of the mind from that very reality. It is, paradoxically, the compulsion to document that dooms photography to transgress the limits of the visible, opening up a terrain that belongs to the imagination rather than to empirical certitude. In his tribute to Barthes, Calvino described the capacity of language to speak about things “that are not”: this was its fundamental difference from photography. Yet, in this story, Antonino takes photography close to the inwardness of the imagination unshackled from the real, and to the irreducible logic of memory, dream, and fantasy. This is also the domain of fiction and, dare one say, of art. It is the rigorous unruliness of fiction— rather than the discursiveness of theory, or the objectivity of history—that becomes the mode in which Calvino fathoms the meaning and possibilities of photography. It is fiction that rescues photography from the risk-averse middle path of empiricism by toppling the eye, and the eye’s mind, into the abyss of the invisible. As he lets go of the hope of capturing with his camera the “essence” of the woman he desires, Antonino stumbles upon his art’s most difficult secret: “Photography has a meaning only if it exhausts all possible images.”