Remembering Nona Faustine’s Powerful Self-Portraits

Faustine’s photography was a love letter to New York—and a fierce assertion of Black presence in public spaces and collective history.

Nona Faustine, Dorothy Angola, Stay Free, In Land Of The Blacks, Minetta Lane, Village, NYC , 2021

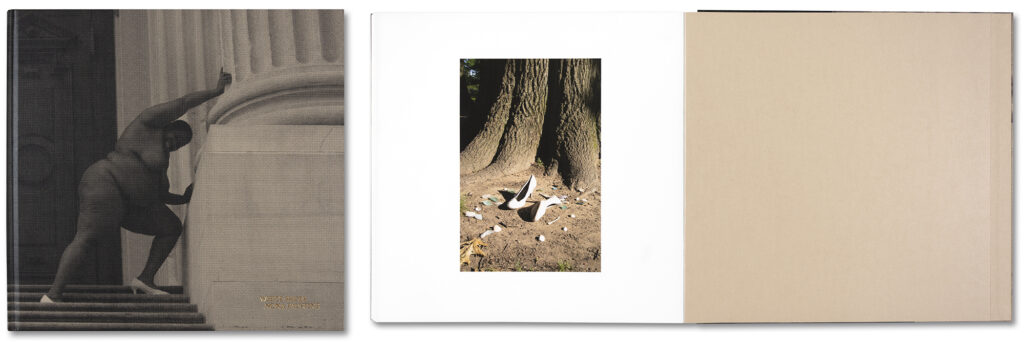

In one of her characteristically powerful self-portraits, the photographer Nona Faustine, who was based in New York until her death in March 2025, bares her clenched white teeth, gritting hard as she lunges forward, attempting the impossible task of toppling a set of classical architectural columns. Her white heel is firmly planted and directed toward the pillar, the object of its potential metaphor: foundational white patriarchy. Appearing on the rough cloth cover of Faustine’s first monograph, White Shoes (MACK, 2021), the drama of her action is a somber invitation to step into another reality and join Faustine in the labor of surfacing history, marking its trace, and upholding those who have been made unknown.

White Shoes is the title for Faustine’s series of self-portraits—oftentimes nude—in which she contorts herself into various poses across the New York landscape. The white heels act as a transporting talisman, allowing Faustine to commune with Black ancestors she has recovered through extensive research and those that are beyond the archive. Each image, often made in collaboration with her sister Channon, envisions Faustine’s connection to geographies and the past: her stunning brown figure locates sites where histories of enslavement once occurred but have subsequently been effaced. Faustine orchestrates her honorific landmarking and directs Channon when to click the shutter.

The book features writings by Faustine, Jessica Lanay, Seph Rodney, and Pamela Sneed, along with an interview with the artist. Rodney, for example, outlines how Faustine’s nude self-possession asserts new ways of knowing the world. Her poignant and vulnerable self-portraits are in dialogue with earlier generations of radical body-performance art by Eleanor Antin, Eiko Otake, Adrian Piper, and Ana Mendieta as well as the photographs of Laura Aguilar, Carrie Mae Weems, Renée Cox, and Carla Williams.

When Faustine mobilizes the hypervisibility of her large, dark-skinned figure, she confronts a visual culture steeped with colorism and fat phobia. Such a body has been involuntarily ungendered, violently stereotyped, discriminated against, discarded, and censored. The physicality of this book, with its exquisite color reproductions, directly counters the elision of Faustine’s flesh—the spectrum of brown hues in her folds, rolls, nipples, dimples, and buttocks—from our cultural and institutional lives.

An incisive, poetic title, printed in light gray, informs each image like a reverberating echo: Of My Body I Will Make Monuments in Your Honor. The hum of Faustine’s writing and photographs deeply affects the viewer and offers an experience of time outside of linear chronologies. Lanay’s essay in part uses the grammatical concepts of the theorist Tina Campt to read Faustine’s photographs as a fantastical future that hasn’t yet happened but must, a future that will collectively counteract the erasure of Black life.

White Shoes unveils a kind of love letter to New York, extending the lineage of photobooks that use the city as a recurring character and backdrop. Since the publication was released, Faustine’s hometown has begun to reciprocate her dedication. In 2024, the Brooklyn Museum, an institution Faustine worked for early in her career, mounted the largest presentation of White Shoes in a solo exhibition for the artist. The impactful show became a New York Times critic’s pick. The same year she was featured in ICP at 50, the International Center for Photography’s fiftieth-anniversary exhibition, completing another important circle in her artistic evolution: she earned her MFA from ICP in 2013. She was also awarded the Joseph H. Hazen Rome Prize and took residence at the American Academy in Rome during fall of 2024. Her daughter Queen joined her, and during their months in the city, Faustine embarked on a project similar to White Shoes, an effort to uncover African diasporic narratives in the historic metropolis.

All photographs courtesy the artist and MACK

White Shoes remains Faustine’s most widely known and celebrated work, and prints from the series are now part of numerous permanent collections, including the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the Brooklyn Museum, and the Museum of Modern Art, New York. These achievements were enthusiastically and beautifully celebrated on her very active social media accounts, now run by Channon. Faustine’s commitment to her home, her multigenerational Black matriarchal family, and the people of New York manifests in White Shoes as a Black feminist text that expertly intertwines love, care, and research, with a scathing critique. As we mourn Faustine in this physical realm, we should hold in memory what her art taught us—that there is never a loss of Black presence. Instead, it is our shared responsibility to remember and cherish those who were once here. Faustine was a conjurer who helps the past haunt us, insisting it cannot be erased.

An earlier version of this article was first published in Aperture, no. 247, Summer 2022.