On Hugh Mangum

On Hugh Mangum

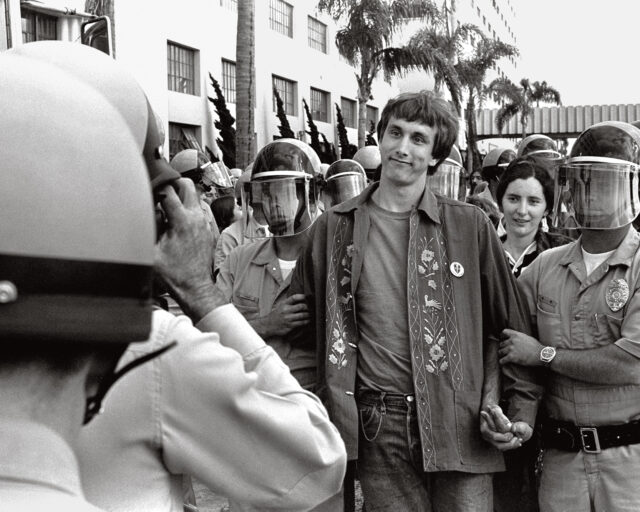

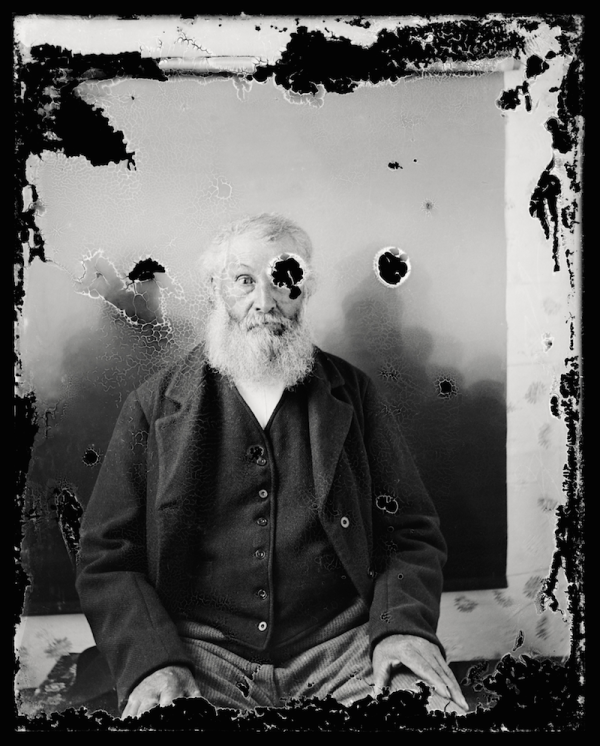

Untitled, ca. 1900–1922: Hugh Mangum, self-portrait. Mangum grasped the power of photography to communicate information or a narrative. He’s using this series to express his identity and personality, and understood that many clients would be seeking the same.

Inside or outside his photo studio, Hugh Mangum created an atmosphere—respectful and often playful— in which hundreds of men, women, and children genuinely revealed their spirits. Born and raised in Durham, North Carolina, Mangum began establishing studios and working as an itinerant photographer in the early 1890s, traveling by rail through his home state, Virginia, and West Virginia. Mangum attracted and cultivated a clientele that drew heavily from both black and white communities. Though the early-twentieth-century American South in which he worked was marked by disenfranchisement, segregation, and inequality—between black and white, men and women, rich and poor—Mangum portrayed all of his sitters with candor, humor, and spirit. Above all, he showed them as individuals, and for that, his work—largely unknown—is mesmerizing. Each client appears as valuable as the next, no story less significant.

Mangum’s life was brief, yet it encompassed momentous shifts amid a turbulent period in American history. Born in 1877, the year the Civil War’s Reconstruction period ended, Mangum died from influenza in 1922, only three years after the end of the First World War and two years after women gained the right to vote. The personalities in Mangum’s images collectively, and often majestically, symbolize the triumphs and struggles of this pivotal era.

A century after their making, Mangum’s images allow us a penetrating gaze into individual faces of the past, and in a larger sense, they offer an unusually insightful glimpse of the early-twentieth-century American South. What follows are facets of this rich collection.

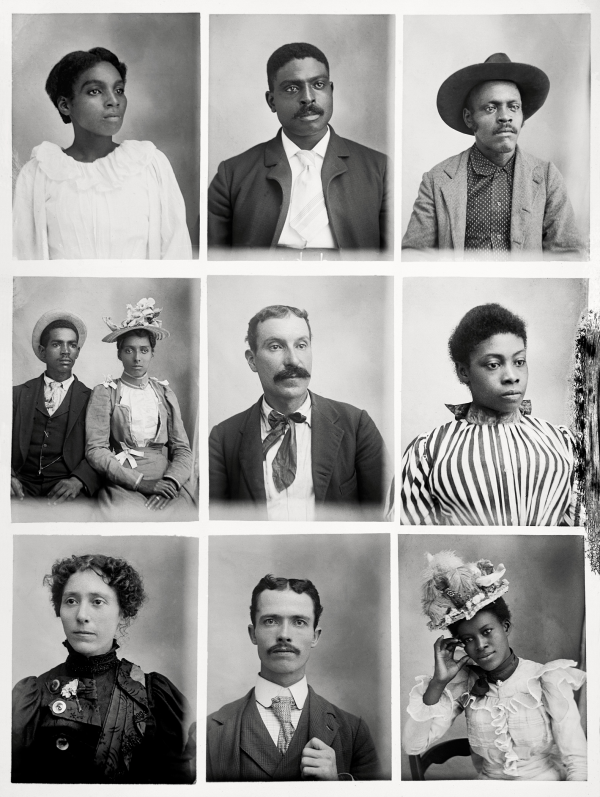

Untitled, ca. 1900–1922: Durham was known to have an unusually prosperous black community. Black-owned businesses included the North Carolina Mutual Life Insurance Company, Mechanics and Farmers Bank, furniture, cigar, and tobacco factories, textile and lumber mills, brickyards, churches, a library, schools, and a hospital. North Carolina Central University, an institution that throughout the Jim Crow era provided professional development for black residents of Durham and beyond, was founded in 1910.

Women

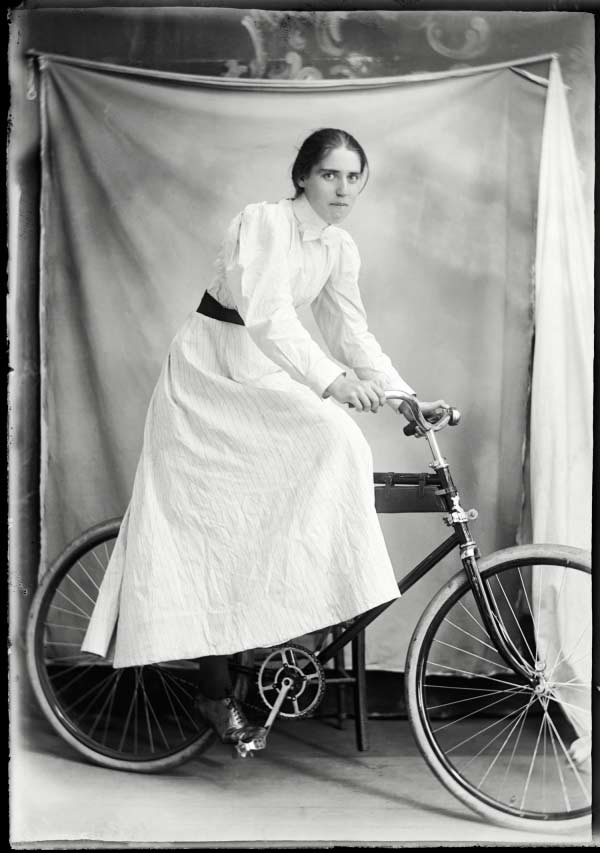

Near the end of the nineteenth century, women on both sides of the color line began to dismantle the barriers that separated the male and female worlds. As the New Woman of the 1890s emerged, the terms of masculinity and femininity were questioned, causing considerable debate and self-reflection. Women claimed the right to education, found employment in positions that were previously reserved for men, and demanded the right to vote. Many women earned their own wages; some lived independently. Political, religious, educational, social, and work-related clubs, both private and public, were formed by women from all walks of life as they redefined their roles in society and as individuals.

The bicycle played a considerable role in female emancipation and subsequently in fashion, as women preferred clothing that allowed more movement. The bicycle embodied the freedom, independence, and mobility of the New Woman. In 1896, Susan B. Anthony exclaimed, “Let me tell you what I think of bicycling. I think it has done more to emancipate women than anything else in the world. It gives women a feeling of freedom and self-reliance. I stand and rejoice every time I see a woman ride by on a wheel . . . the picture of free, untrammeled womanhood.”

Untitled, ca. 1900–1922: In this image a young woman balances precariously on her bicycle. The instability captured here perhaps brings her back to the first time she rode a bike, exploring the freedom and mobility it bestowed.

Technology

Over the course of thirty years, Mangum used several types of cameras and formats.

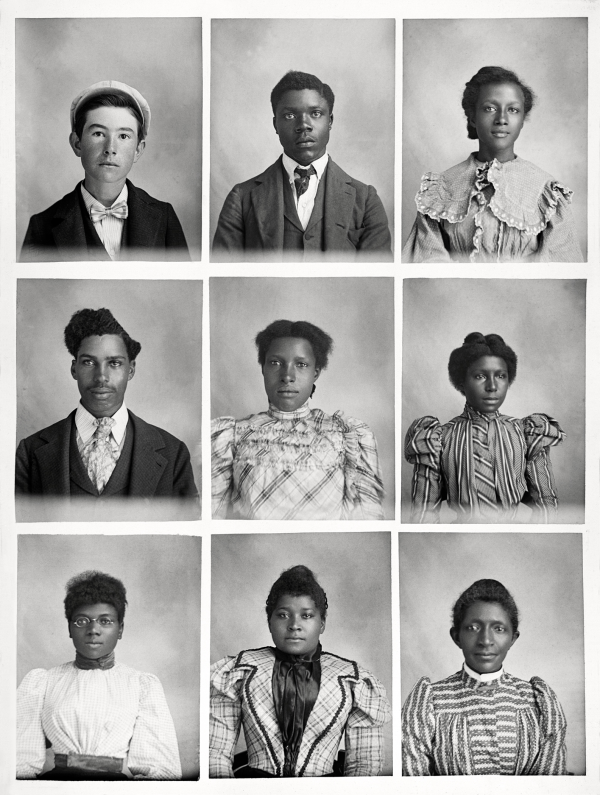

He often used a Penny Picture Camera, which allowed multiple and distinct exposures on a single glass plate negative. Depending on the circular or square template, one glass plate might contain anywhere from six to twenty-four images. This was ideal for creating inexpensive novelty pictures as multiple sitters could be photographed on one negative, reducing cost and labor.

Notably, the Penny Picture Camera worked in a step-and-repeat process in which the negative holder was repositioned behind the lens after each exposure. As a result, the order of the images on the negatives represents the order in which Mangum’s diverse clientele rotated through the studio, the negatives reasonably representing an afternoon or day’s work for this gregarious photographer.

Black Community

There are no indications that Hugh Mangum intended his photographs to serve any political purposes, but it is likely that for many of his sitters, in fact they did. By the turn of the twentieth century, African Americans had long engaged the power of photography in order to challenge racial ideas, as well as to visually create and celebrate black identity. Mangum’s sitters used the images to emphasize accomplishments, prosperity, beauty, and individuality. They shared them with friends and made them the foundation of family photo albums, ultimately shaping their own identities and those of future generations.

Mangum lived during the same period as acclaimed black thinkers like Booker T. Washington, Ida B. Wells-Barnett, W. E. B. Du Bois, and Zora Neale Hurston. These were some of the most difficult years in African American history. Although there are no tidy dates separating the phases and forms of racial discrimination, the removal of federal troops at the end of Reconstruction was arguably the advent of Jim Crow laws, and lynching peaked in the 1890s. Yet at the same time Mangum was making portraits, members of the black community were building on the strength of their own values and institutions, and cultivating resistance to laws and customs that excluded them.

Untitled, ca. 1900–1922: Durham was known to have an unusually prosperous black community. Black-owned businesses included the North Carolina Mutual Life Insurance Company, Mechanics and Farmers Bank, furniture, cigar, and tobacco factories, textile and lumber mills, brickyards, churches, a library, schools, and a hospital. North Carolina Central University, an institution that throughout the Jim Crow era provided professional development for black residents of Durham and beyond, was founded in 1910.

Deterioration

During Mangum’s lifetime he likely exposed thousands of glass plate negatives. Most of them were destroyed through benign neglect after his death or are now lost, as were almost all records of the names and dates associated with them. The images that survived—nearly eight hundred glass plate negatives—were salvaged from the tobacco pack house where Mangum built his first darkroom. For decades, the negatives caught the droppings of chickens and other creatures living in the pack house. Today they are in various states of an ongoing deterioration; even the most controlled environment cannot halt the creeping decay. The effect can be poetic, adding a layer of meaning to the image that would otherwise be absent. Some plates are broken and on others the emulsion is peeling away, but the hundreds of vibrant personalities in the photographs prevail, engaging our emotions, intellect, and imagination.

Untitled, ca. 1900–1922: In this image, the surprised expression on the man’s face fits perfectly with the position of the deterioration that befell the negative on which he is photographically etched.

All images courtesy of Hugh Mangum Photographs, David M. Rubenstein Rare Books & Manuscript Library, Duke University. Contemporary reprints by Sarah Stacke.