Report from Oslo

With a Tom Sandberg survey exhibition this summer as well as the 2015 edition of the sprawling Fotobokfestival this fall, the Norwegian capital’s photography scene is flourishing. This article first appeared in Issue 19 of the Aperture Photography App.

Installation view of Diptych, Kunstnernes Hus, 2015. Installation shot by Christina Leithe Hansen

In early summer in Oslo the sun sits high and the light, almost tinted silver, is plentiful. By mid-September, the white nights are over and light is in dwindling supply. My summer was bookended by trips to the Norwegian capital. In June, I visited a Tom Sandberg exhibition at Kunstnernes Hus. Titled Diptych, the exhibition, curated by Sune Nordgren and Ida Kierulf, was divided between the venue’s two long rectangular gallery spaces, each amply flooded by skylights. The space was well suited for a show of work by the late Norwegian photographer (Sandberg died in 2014) who trained his camera on the surfaces of everyday objects and figures—a jet black sedan, a tunnel opening into a gentle curve, the varied texture of clouds, individuals turned away from the viewer—to create a singular body of quietly observed photographs.

Installation view of Diptych, Kunstnernes Hus, 2015. Installation shot by Christina Leithe Hansen

Sandberg had a knack for enigmatically rendering the world in abstract compositions, almost magically de-familiarizing the ordinary and elevating the mundane to the monumental through his exacting attention to light, form, and volume. The illuminated galleries of the functionalist Kunsternes Hus provided an apt space to celebrate a photographer whose work often meditates on modulations of light. With their quotidian subjects, and a puzzling lack of information about specific locations, Sandberg’s photographs often feel detached from time and place. Many images echo the pictorial clarity that defined the work by titans of modern photography, such as Paul Strand or Edward Weston. Sandberg, however, provides enough clues—a repeated theme of modern transportation, for example—to locate viewers in a contemporary moment. Though the show included a large number of works, Diptych wasn’t meant to be a retrospective, but instead served as an elegiac tribute to a beloved, influential—and now missed—photographer.

Installation view of Diptych, Kunstnernes Hus, 2015. Installation shot by Christina Leithe Hansen

When I returned to Oslo in mid-September, I attended the Fotobokfestival Oslo, a program aimed to engage the photobook as an artistic medium through a combination of exhibitions, workshops, lectures, and other activities. Organized by the Norwegian Association of Fine Art Photographers and Fotogalleriet, an artists-run space founded in 1977 by Tom Sandberg along with Dag Alveng and Bjørn Høyum. For this year’s iteration, German photobook expert Markus Schaden was invited to present the mobile edition of his new project The PhotoBookMuseum. Previously the proprietor of a Cologne-based specialty bookshop that earned a cult following before photography books became a fetishist’s delight, Schaden is an enthusiastic proselytizer of the photobook. At Fotogalleriet, he installed an annotated study of Dutch photographer Ed Van Der Elsken’s classic 1956 Love On the Left Bank, which tells a fictionalized love story. With the entire sequence of the book mounted to the wall, this footnoted presentation illuminated aspects of the book’s publishing history, picture editing (by showing marked up contact sheets), as well as the volume’s connections to contemporaneous counter-cultural activity, such as the rise of the Lettrist International and the publication of Guy Debord’s Society of the Spectacle.

Installation views of Fotobokfestival Oslo, September 11-20, 2015

Meanwhile, in Youngstorget, a main city square, Schaden and his team assembled a mobile version of their The PhotoBookMuseum, comprising six shipping containers organized in a radial formation. Each container featured a presentation of an individual photography title, including PIGS by the Spanish photographer Carlos Spottorno, a book about the 2008 economic crisis cleverly packaged to look like the Economist magazine, which has referred to the southern European countries of Portugal, Italy, Greece, and Spain with the derogatory acronym PIGS. Other featured books included Carolyn Drake’s Two Rivers, a project that follows two rivers in Central Asia to document the shifting political and economic conditions of the region; Oliver Sieber’s Imaginary Club; Ricardo Cases’s Paloma al Aire; Andrea Diefenbach’s Country Without Parents; and Ali Taptik’s Metropol Yesili.

Installation views of Fotobokfestival Oslo, September 11-20, 2015

The highlight of the installation, though, was the physical manifestation of a space seen inside a classic photobook: a facsimile recreation of Café Lehmitz, the grimy site seen in Anders Peterson’s classic 1978 book of the same name that documented the drunken antics of the café’s louche patrons. The recreated Lehmitz served up drinks and snacks for the sizable crowd that attended the opening of the Fotobokfestival, turning a photobook into a form of theater. The mobile PhotoBookMuseum drew large crowd of curious visitors, fulfilling the organizer’s stated aim of the bringing the narrative of the photobook to an audience beyond the aficionados, suggesting that Schaden may be on to something when he earnestly dubs the photobook a “visual Esperanto.”

Installation views of Fotobokfestival Oslo, September 11-20, 2015

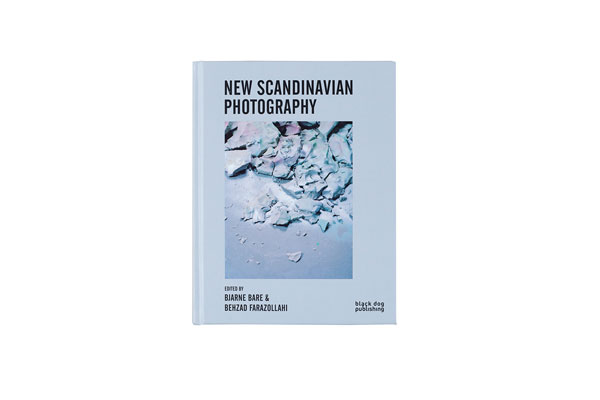

The end of the festival also saw the launch of New Scandinavian Photography, a survey publication co-edited by Bjarne Bare and Behzad Farazollahi, founders of MELK, a non-profit space opened in 2009, that aims to connect the discourses of photography and contemporary art. “Oslo stands out because there is a strong generation of doers, who are creating spaces and a discourse that didn’t exist,” Bare, who is now based in Los Angeles, mentioned in a recent conversation. “Oslo is relevant and alive.”

Cover of New Scandinavian Photography (London: Black Dog Publishing, 2015)

The book features work made over the last decade by sixteen Scandinavian photographers, including figures such as Torbjørn Rødland (featured in the new issue of Aperture magazine) and Asger Carlsen, the New York-based Danish photographer known for his grotesque digital manipulations of the body. Other artists include Mårten Lange, Kristina Bengtsson, Nicolai Howalt, Marthe Elise Stramrud, among others, who, through a diverse range of practices, produce work that eschews traditional photographic observation in favor of exploring photographic ontology, or at least an expansive approach to the medium. With a number of essays by an international roster of curators and scholars, the volume is a useful introduction to a group of photographers whose work is very much aligned with some of the concerns animating contemporary photography today, underscoring the idea that the photography scene in Scandinavia, more broadly, is very much relevant and alive.

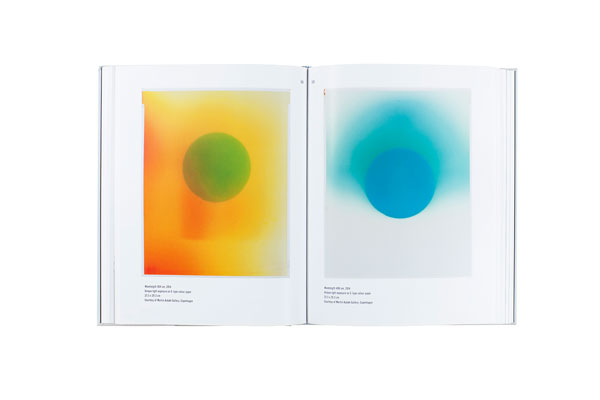

Pages of New Scandinavian Photography, including photographs by Nicolai Howalt

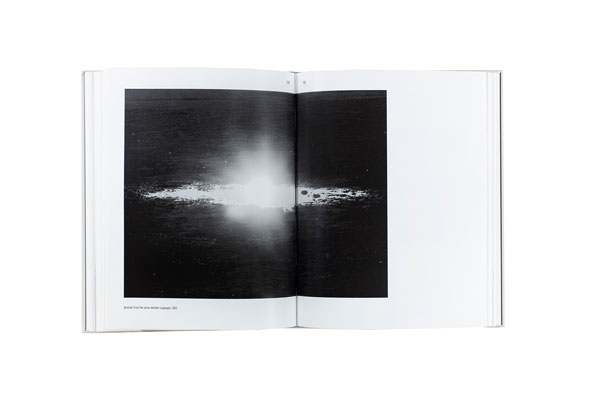

Pages of New Scandinavian Photography, including photographs by Mårten Lange

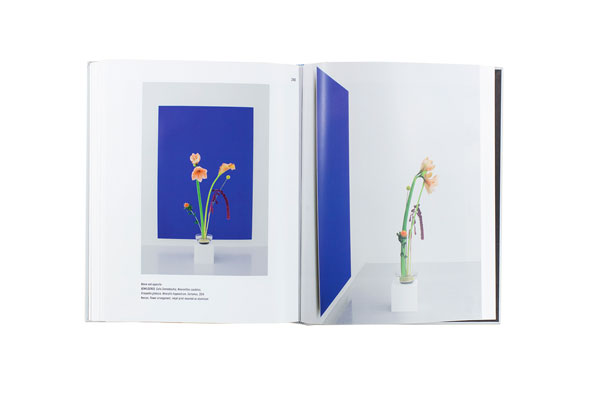

Pages of New Scandinavian Photography, including photographs by Marthe Elise Stramrud