Photo-Poetics: An Anthology at the Guggenheim

In a new exhibition at the Guggenheim, ten contemporary artists investigate photography on the verge of transformation.

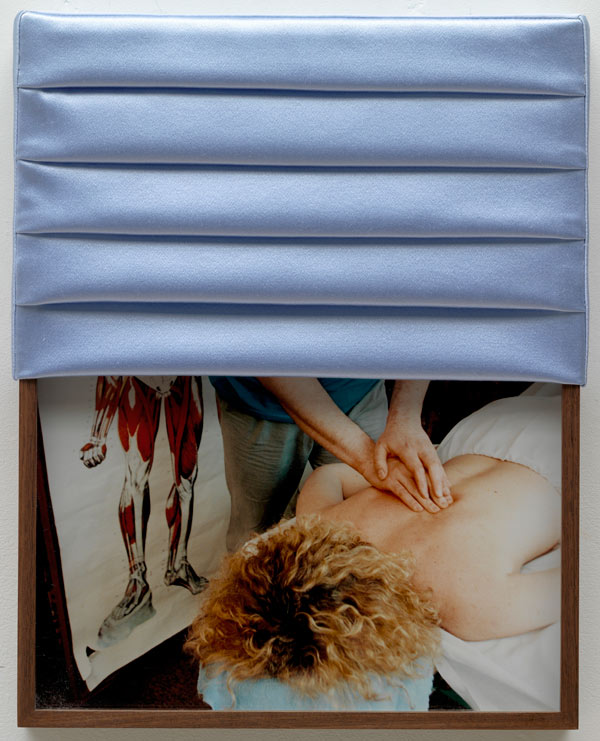

Kathrin Sonntag, Mittnacht, 2008 © Kathrin Sonntag Installation view: Photo-Poetics: An Anthology, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York. Photograph: David Heald

I have to confess that the organizing premise of the Guggenheim’s new exhibition Photo-Poetics: An Anthology struck me, at first, as unfortunately narrow. Curator Jennifer Blessing, working with assistant curator Susan Thompson, presents ten photographers as illustrating contemporary strategies for engaging a medium that (to borrow a phrase from the introductory wall text) “seems poised to evaporate into digital oblivion,” and this technical emphasis doesn’t always set the work to good advantage. In particular, Claudia Angelmaier’s aggressively understated, lusciously opaque prints of backlit, blank-side-up art postcards—female models who famously turned their backs on male artists from Ingres to Richter afforded the chance to reject our gaze all over again in tertiary reproduction—are at their least interesting as comments on photography.

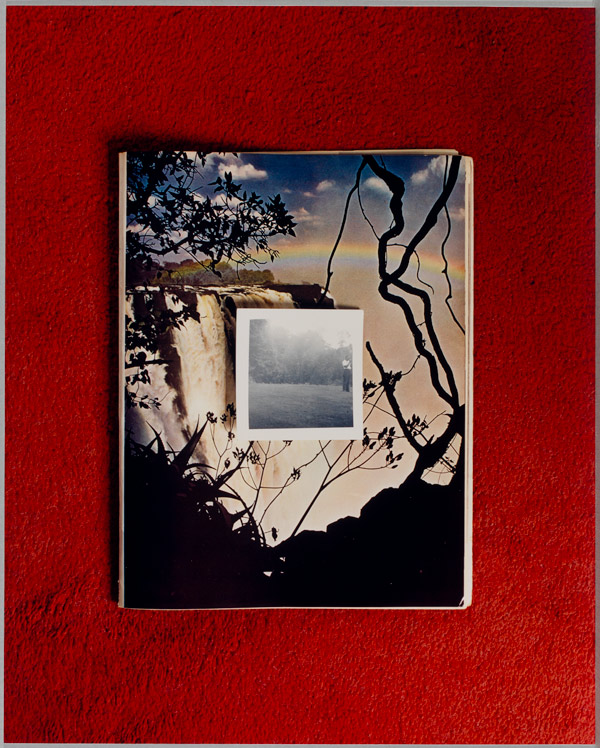

Leslie Hewitt, Riffs on Real Time (4 of 10), 2006–9 © Leslie Hewitt

But of course the formal premises of the strongest work in the show are equally narrow, and for good reason: the narrower the starting point, the broader the range of possible outcomes. Take Leslie Hewitt’s intricately open-ended, surprisingly expansive Riffs on Real Time (2006–9). Each modestly sized color print is a complete miniature of photography as we actually experience it: A found snapshot, usually with white borders, often making discreet allusion to the civil-rights movement or other historically resonant material, is rephotographed atop a page from a magazine, a larger photo, or a sheet of paper with cryptic, typewritten abbreviations or ballpoint graffiti letters, which is itself set against orangish wood grain, red-painted stucco, or some other stand-in for a bourgeois floor or museum wall. The whole thing feels as pleasantly provisional as a stack of art books on a coffee table, and instead of making the expected institutional critique—although it certainly does that, too—what it really suggests is that the image is on par with its display, all of it equally solid or transient.

Lisa Oppenheim, The Sun is Always Setting Somewhere Else, 2006 © Lisa Oppenheim. Installation view: Photo-Poetics: An Anthology, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York. Photograph: Owen Conway

Likewise Erica Baum’s Naked Eye series (2008–), garishly colored, modestly sized inkjet prints the artist makes by ruffling open old pulp paperbacks with tinted edges and shooting them from the sides. In Shampoo, a vertical section of a sexy movie still is framed in the cornflake color of cheap paper and not-quite-vertical green lines; in Slept, a man’s head, pictured in black-and-white and compressed by the angle of the paper, is squeezed between columns of isolated words; and in Amnesia, the wavy edges of water-damaged pages bring to mind the conventional TV cue for a “dream sequence.” Ubiquity denatures value, whether of language or art, but by taking image saturation as her starting point, Baum leaps from curation to re-creation and neatly preempts the problem.

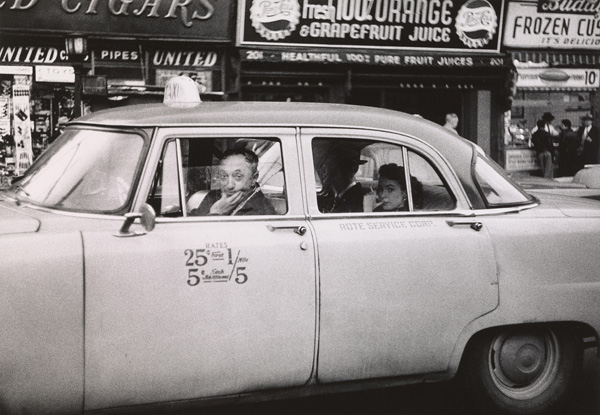

Moyra Davey, Trust Me, Installation view: Photo-Poetics: An Anthology, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York. Photograph: David Heald

Moyra Davey’s Trust Me (2011), sixteen stately moments of household silence—a white radiator spotted with sunlight, framed photos leaning in a corner, an open medicine cabinet, a stuffed rabbit with enormous droopy ears—which the artist folded in sixths, sealed with green tape, mailed to Lynne Tillman, unfolded again, and pinned to the wall, although it lingers more than Baum or Hewitt’s work in the sensual beauties of the chromogenic print, treats its simple formal idea as a mechanism, not an end.

Erin Shirreff, UN 2010, 2010 © Erin Shirreff

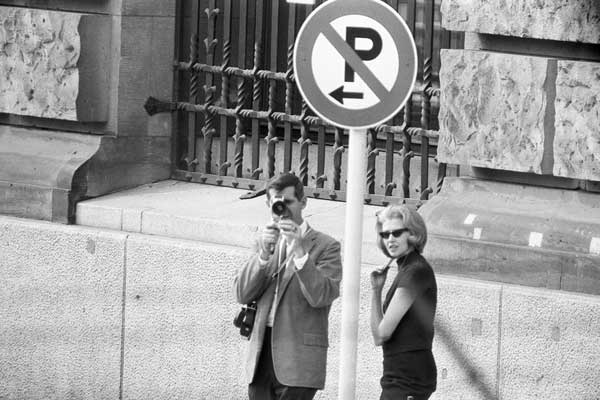

Lisa Oppenheim, in The Sun is Always Setting Somewhere Else (2006), looks at alienation, geography, and the curiously imbalanced sharing of experience made possible by the internet: she prints snapshots of sunsets posted by American soldiers to the photo-sharing site Flickr, rephotographs them against real sunsets in Fire Island, New York, and indicts the comforts of reflexive patriotic nostalgia by projecting the resulting images with an old-fashioned carousel. Kathrin Sonntag looks at composition, quiet, and the inexhaustible glories of black-and-white with a series of elegant studio still lifes; Sara VanDerBeek looks at history more formally, with equally handsome black-and-white photographs of sculptural collages of images of famous artworks of the past; Elad Lassry, with cheeky, stage-set colors, looks at Sarah Charlesworth, or so her prominent name-check in the catalogue would suggest; and Erin Shirreff, in UN 2010 (2010), looks at the United Nations building the way cynics, conservatives, and impatient revolutionaries might all agree that it deserves to be looked at, with what purports to be a portrait video that was actually assembled from a series of stills.

Elad Lassry, Untitled (Woman, Blond), 2013 © Elad Lassry

I don’t expect digital oblivion to claim photography any more than photography itself killed painting. The varied formal strategies on display in Photo-Poetics make clear that photography is defined less by its mechanism, at this point, than by its style—it’s less a technology of recording than a mode of looking. But what digital oblivion may at last do, by taking upon itself the mantle of apocalyptically threatening novelty that has burdened photography since its invention, is to make it normal—one more medium of art-making among many.

Photo-Poetics: An Anthology is on view at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York through March 23, 2016.