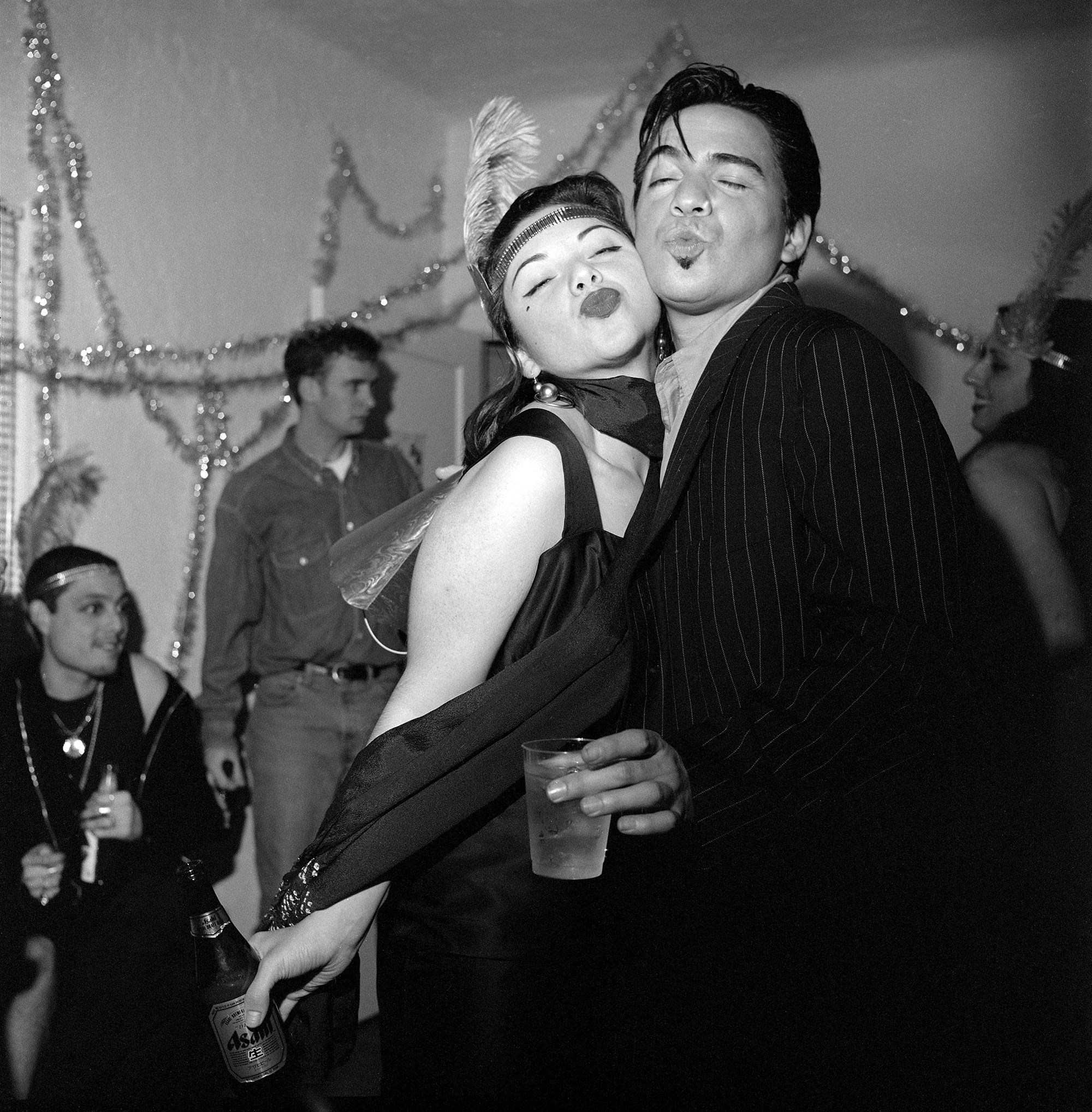

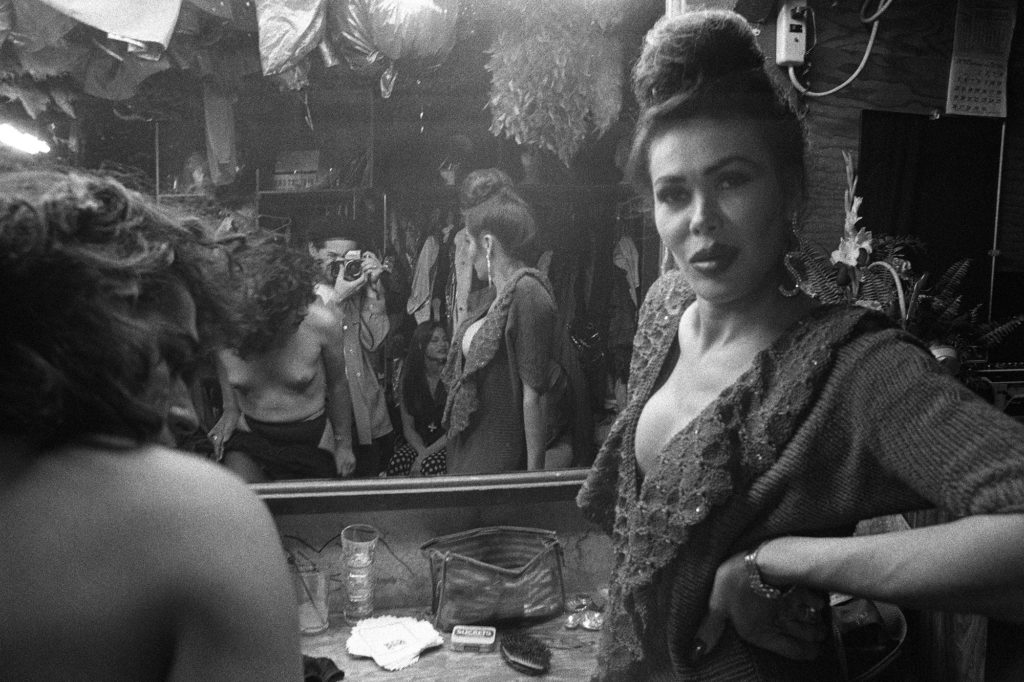

Reynaldo Rivera, Connie Rivera and Mario Calvano, Echo Park, 1990

If the photographer Reynaldo Rivera didn’t exist, a Hollywood more interested in queer and Latinx people might have invented him. As detailed in Reynaldo Rivera: Provisional Notes for a Disappeared City (2020), Semiotext(e)’s marvelous new monograph, Rivera sidestepped tragedy through talent and will. He made transformational photographs of subjects transforming themselves, many now dead in places now shuttered or, worse, disappeared. What separates Rivera’s work from that of his peers—the loving slums of Nan Goldin, the horny social-butterfly lepidopterarium of Christopher Makos, Alvin Baltrop’s formal observations, the personality crises of Peter Hujar—might be a rejection, or perhaps disinterest, in distance. Rivera’s photographs of trans women and drag artists, of artists and scenesters and lovers and friends, in and out of LA’s legendary Latino bars and party houses, thrill with presence without flaunting their access. “If people are busy living out myths you don’t like,” Samuel R. Delany writes in his wild epic novel Dhalgren (1974), “leave them to it.” Rivera’s subjects were busy. They were living. He clearly loved them. He made real myths with them.

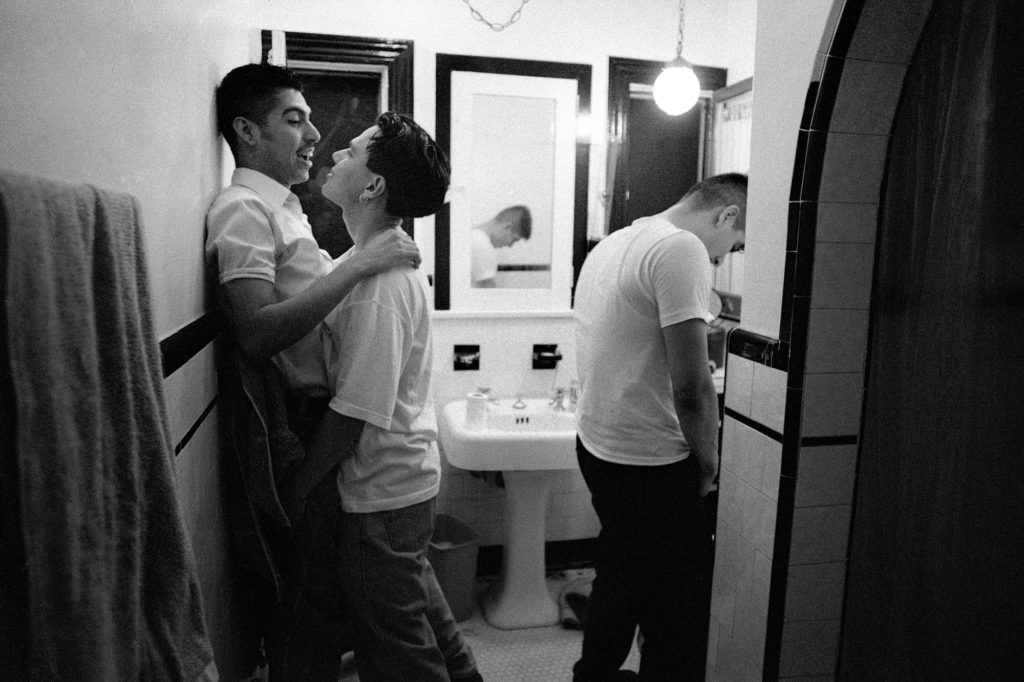

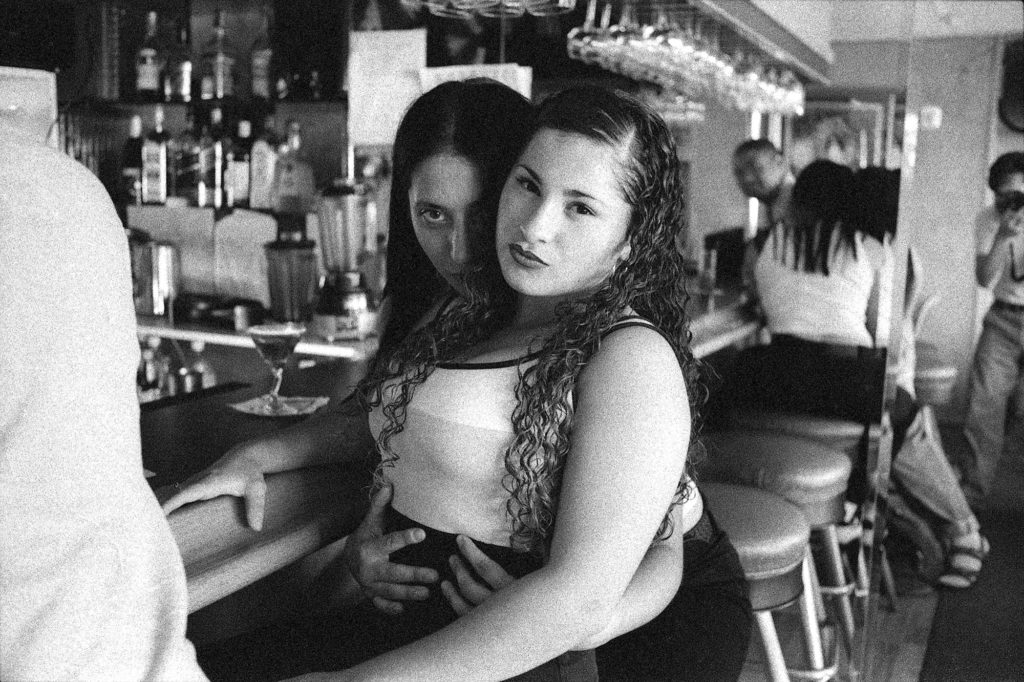

In Rivera’s photograph Richard Villegas Jr., friend, and Enrique, Miracle Mile (1996), two men embrace each other in a well-lit bathroom—while another man nearby pisses into a urinal—all so busy in their joy. Another shows off the pride of a patron at the Silverlake Lounge in 1995, his cowboy drag as white and spotless as the toilet seat his boot rests on, at least in Rivera’s frame. There’s an image of “Vanessa” cross-legged and offering an expression of feeling herself so supernatural it transcends place and time, and so natural it could only come from a person truly at home. The run of photographs of Tatiana Volty, her story lovingly recounted by Luis Bauz, is tale-ready for its close-up.

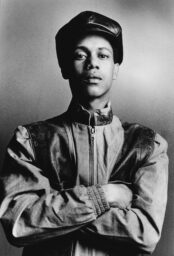

Such intimacy arose from estrangement. Rivera’s mother was born in Mexico and left for Stockton, California, when she was sixteen and pregnant, where she met his father, also Mexican-born and two decades older. They quickly married and separated; Reynaldo and his older sister, Herminia, shuttled between houses and Southern California border towns. Their father kidnapped them when Rivera was five and ditched them with his family in Guanajuato, in a small house with no running water and an abusive grandmother. After four violent years, they returned to their mother and the American racism of Glendale, California, in the 1970s.

Rivera’s father occasionally interfered with his reintegration by hijacking his adolescent son for extended stays in the San Joaquin Valley, where he worked seasonally at a Campbell’s Soup cannery or picking cherries. Rivera stayed in the rundown SROs with him, worked the fields, befriended homeless people in town and robbed stores with them, and found himself spellbound by the photography books he uncovered at thrift stores. In sixth grade, back at home with this mother and beguiled by the lives and work of Golden Age glamour girls like Lucha Reyes, he was arrested for selling drugs; by fourteen, he’d left high school and returned to Mexicali. He worked at his father’s liquor store until his father shot a gangster, who died in the street, prompting his father to disappear with Rivera’s green card. Fortune reunited them at a bus station in Calexico, and they returned together to the Stockton cannery. Rivera’s dad had a side hustle fencing stolen goods, including a Yashica that Rivera stumbled on one summer day. “And then the genie came out of the bottle,” he said. “I thought if I could capture these moments, keep them on file, I could find some kind of order. … It was a kind of alchemy. It became my thing.”

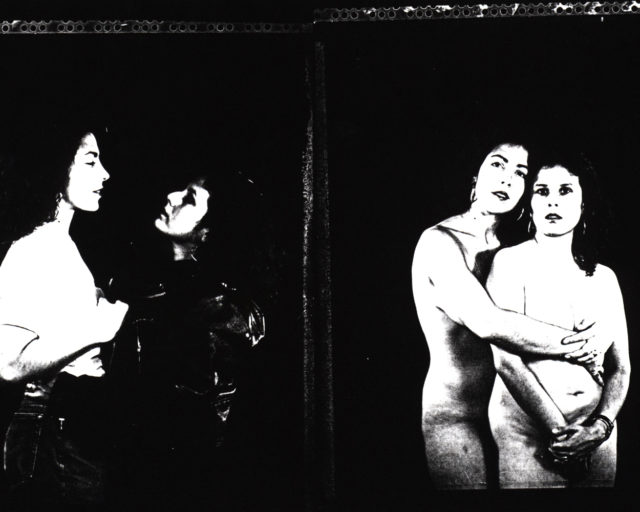

He got a Pentax K1000 and took pictures of Herminia; he returned to Mexico City in 1983, went to the bedroom in which someone had killed his step-grandfather with a machete, and photographed the blood stains across his sheets and framed pictures of saints for a series that empathically struggles against making a crime scene into a still life. Back in Los Angeles, he found worlds of people building lives for themselves by whipping up their own orders of alchemy. He photographed the icons Siouxsie Sioux and Sade and Annie Lennox, sometimes selling his work to the LA Weekly.

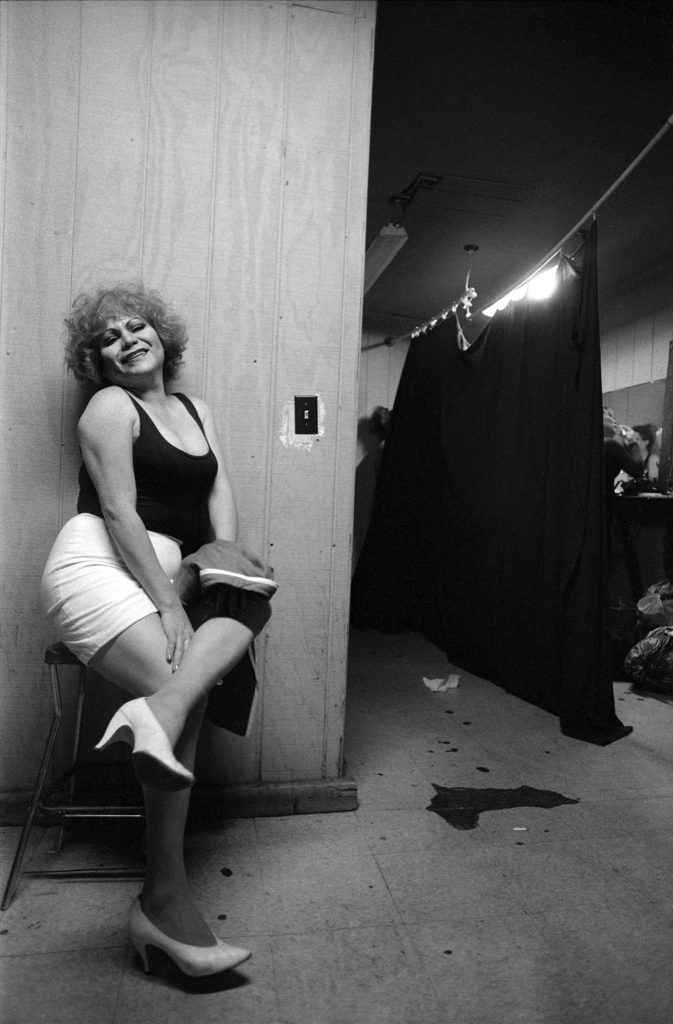

On La Brea, Miss Alex lip-synched for tips at the Latino drag bar La Plaza; in Mexico City, she authored a highly fictionalized newspaper column detailing her exploits among the Hollywood elite. Through Rivera’s lens, she inhabits both worlds at once.

Tina, the face of the artsier bar Club Mugy’s, sometimes impersonated Michael Jackson (thus, in Chris Kraus’s formulation in her perceptive essay for the monograph, working as “a man, dressed as a woman, impersonating a man”), and sometimes called on her Thai identity to showcase pan-Asian displays of femininity, from dragon lady to geisha. Such indeterminacy could get performers canceled today, but in the late ’80s and early ’90s, artists on the outskirts looked everywhere they could for a reflection. They developed a visibility, almost photosynthetic in how it distilled nutrition from flashes of recognition. Rivera photographed them in dramatic black and white, often straight ahead and center-framed, with the photographer in their mirrors’ reflections. Rivera’s subjects display the fruits of their labor—their glittering gowns, their tits, themselves—in dusky arrangements that call to mind LA noir and Hollywood screen tests, but mostly, embrace shadows as just another kind of light.

All photographs courtesy the artist

In a riotous back-and-forth at the close of the book, Rivera and international treasure Vaginal Davis carry on and gossip about the stars of these demimondes, the party people of pregentrified Silver Lake and Echo Park, like Alice Bag and Taquila Mockingbird, and all the dead and deadly serious and drop-dead glamourous. (The pair deserves a genius grant to host double-decker tours of Los Angeles.) There’s sometimes a rush of ruin porn when it comes to these matters: all the wreckage from AIDS and crack and America’s lethal relationship with its transgender family members, all the bars lost to landlords’ greed and our refusal to see nightlife as anything other than a source of “urban revitalization.” Self-invention and self-harm so often fit together, like a hand in a white silk glove. These photographs demand resistance to all that. They marvel at what was made, not how cinematic it looked in destruction.

“We were all thought to be superficial,” Rivera writes of the people around him. “The majority of the city was not white and was not here to be a star or to be in the industry, the majority of us were either born into this dream world or ended up here for other reasons.” Those reasons are all over the faces of the people Rivera photographed—people making the myths that really power Los Angeles. They still exist and must endure.

Reynaldo Rivera: Provisional Notes for a Disappeared City was published by Semiotext(e) in December 2020.