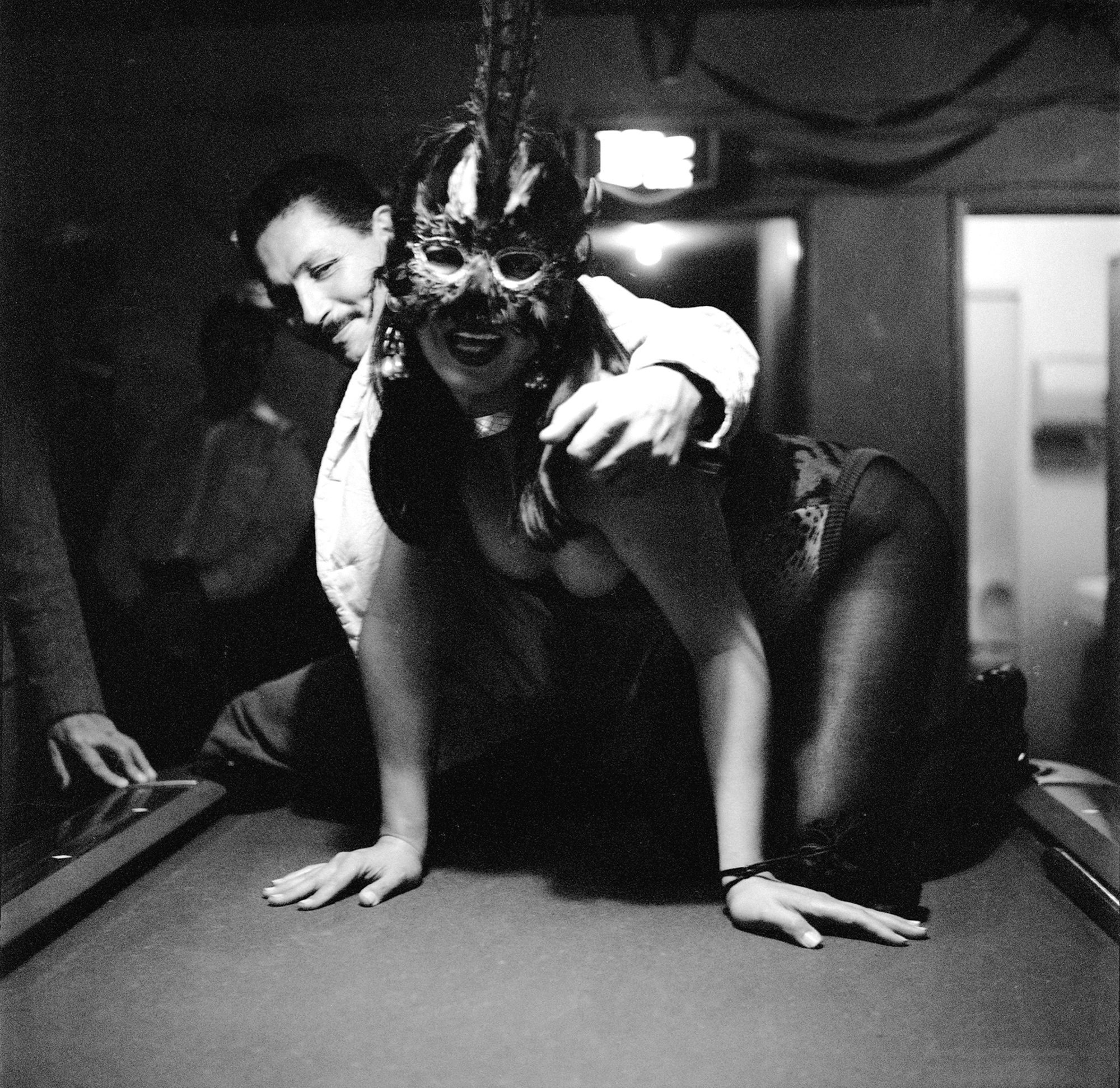

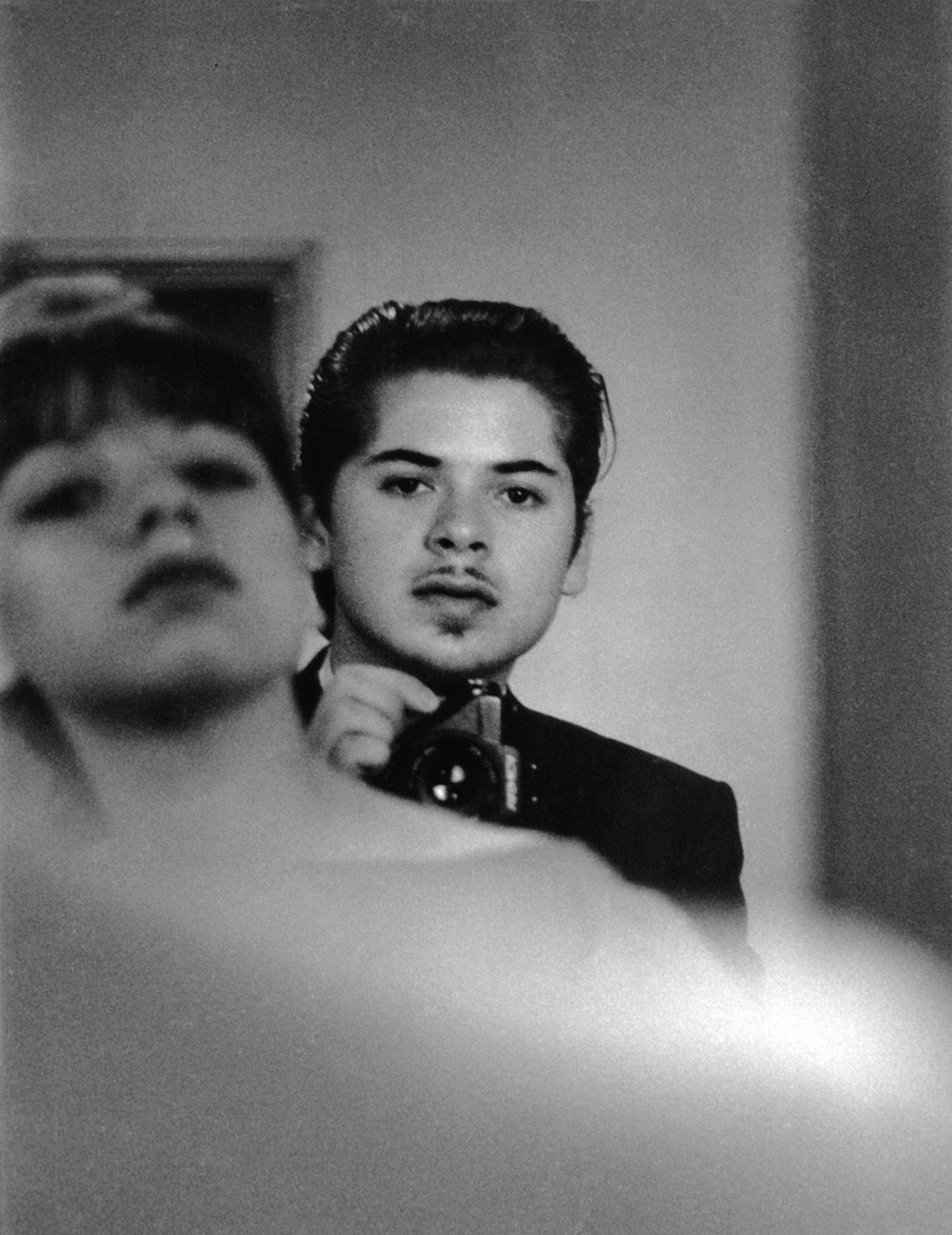

Reynaldo Rivera, Little Joy Jr. Bar, Los Angeles, 1997

In Reynaldo Rivera’s life there are three fires, two of which nearly wiped out his life’s work.

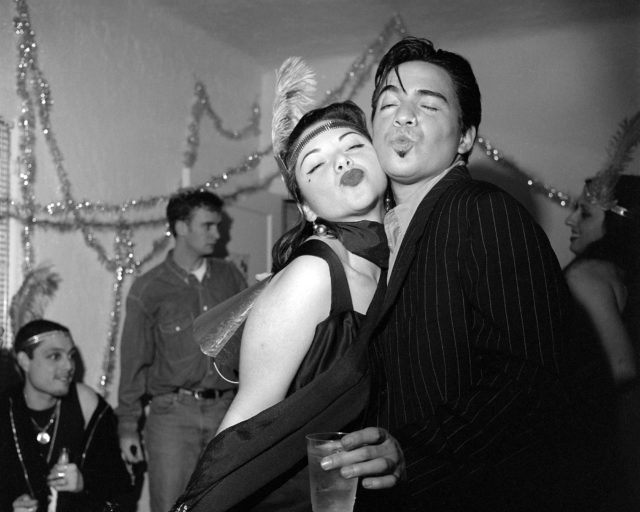

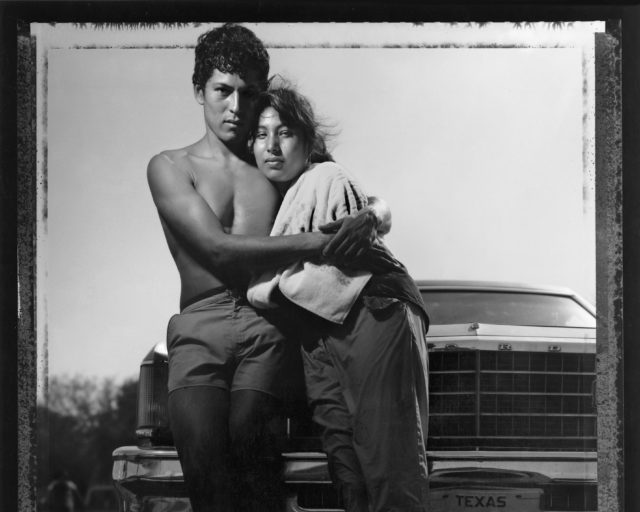

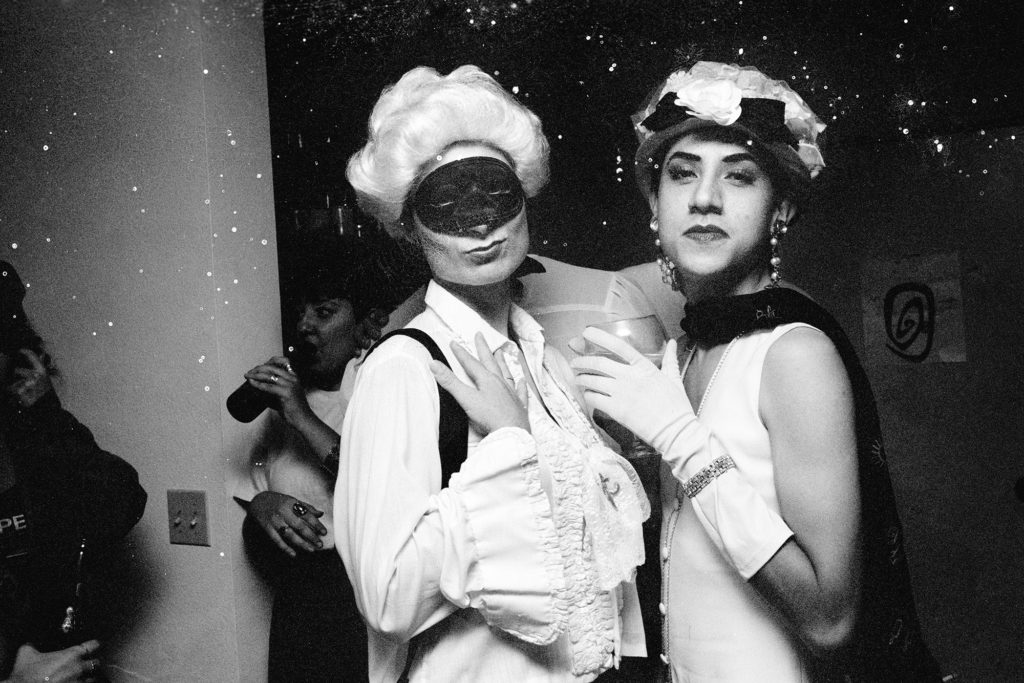

Rivera has been taking photographs for the majority of his life: of friends, lovers, strangers, performers, and those who watch them, mostly in and around Los Angeles. Some document the sun-cracked landscapes and ladies who cleaned the SRO hotel rooms he stayed at in Stockton, California, where, as a teen, he worked seasonally in a Campbell’s soup cannery to support his picture taking and glam thrift habit. Later, as his world grew, he would take pictures in Mexico, Europe, Central and South America, but it’s mainly his photographs of LA scenes in the 1980s and 1990s that are driving an unprecedented institutional interest in his work. These images interpolate every facet of the word scene. Scene as in the East LA scene, the drag scene, the queer scene, the punk scene, the art scene, impressions of a greater scene created by the mix of genders, classes, and orientations milling about the house parties, drag bars, music shows, and bathrooms captured by Rivera’s camera. It’s hard not to cry. Mexican kids growing up under the shadow of the Hollywood sign are haunted by a glamour we’re constantly told is not ours.

The scenic quality of Rivera’s lens was pressed into him by an early love of silent movies and glamorous Mexican singers such as Lucha Reyes and Toña la Negra. “When I was working in Stockton, there was this big used bookstore. The Filipino lady that worked there really liked me. She would let me take boxes of books for like three dollars. I would devour old photo magazines and old movie star magazines because I had nothing else to do. That was my education.” At fifteen, Rivera was rifling through a box of stolen stuff outside the St. Leo Hotel, where he stayed with his father during cannery season. He spied a camera and asked about it. “My dad was like, ‘You want it? Give me 150 bucks.’ I was making a lot of money at this point—well, for that time. And I bought this fucking, broken-down-ass camera. I didn’t even know I could have bought a new camera for a hundred bucks. Some poor tourist probably got whacked over the head for it.” If the bookstore was his aesthetic education, the local Fotomat was his technical education. “I didn’t even know the light meter wasn’t working. I figured out how to load the film, and I would look through this thing, and I couldn’t figure out what anything was. None of my images came out. I started asking the girl at the store, ‘What do you think is going on?’ She taught me how to get an image. She explained that if it was darker I needed to go slower. Basic things.”

We’re sitting at an iron bistro table in the front yard of the large, two-story Victorian Rivera shares with his husband, Christopher Arellano (Bianco to friends), in the Lincoln Heights neighborhood of Los Angeles. There are fruit trees all around—persimmons, limes, pomegranates, lemons, and oranges, some hanging on to their branches, some smooshed and bleeding on the ground, all lightly powdered in smog dust from the mechanic shop next door. In the backyard—weed, herbs, little red-pepper plants, and a wounded dove in a wooden cage. The sun is setting. We’re having doughnuts and coffee. I want to talk about the fires, I say, because I know there are two of them.

“Well, two big ones,” he explains. “There was one before, but let’s just say the first real one was with my ex-boyfriend Steven, after he poked my eye out. Sliced it in half with a piece of glass.” According to Rivera, he ran into Steven at the Dresden Room in Los Feliz. They both got drunk, were removed from the premises, and went back to Rivera’s Echo Park apartment on Laguna Avenue, site of many of the louche gatherings in the background of his party photographs. Steven asked if Rivera was sleeping with his ex-girlfriend. “He always said to me, ‘Whatever you do, tell me the truth!’” Rivera answered yes, and Steven proceeded to trash the apartment, at one point breaking a window with his head. Rivera lunged toward him, and Steven spun around, slashing at his face with a shard of glass. Afterward, Rivera went out to meet some other friends, one of whom happened to be a doctor. She convinced Rivera to go to a hospital, where he underwent emergency surgery, and he finally returned to his apartment two days later. “I walked in, and there’s this little fogata, a pile of burned shit in my living room”—Steven had tried to set fire to Rivera’s life’s work. “He must have been holding the negs and trying to burn them one by one.”

Rivera was born in Mexicali, in 1964, and pinballed between cities on both sides of the U.S.–Mexico border throughout his childhood, sometimes escorted back and forth by his father, who worked as a fence for stolen goods, which sometimes included Rivera and his sister. “My dad kidnapped us and took us to Mexico in 1969. We came back to the U.S. in 1975. It was a different world. You didn’t have to be told that everything Mexican was inferior, you could just feel it.” That feeling permeates much of what gets stamped as “Latino culture” in a city whose most influential export is movies that portray Latinos in a limited number of caricatured roles or presents Latino culture disingenuously filtered through a folkloric lens. As an actor, I, too, have been guilty of ethnic pose, of attempts to make the word Mexican broadly legible to the wider culture, to say nothing of the semantic welter that is Latinx—all due respect to this publication—a word we are both ambivalent about. “I’m Mexican,” Rivera says. “In English, Mexican doesn’t have a gender. It’s already gender neutral. I don’t need to get that complicated.”

Rivera switches seamlessly between pronouns, often using several to describe the same person. He was versed in fluidity before there was a lexicon to describe it—the girls were the girls, whether they had dicks or not. Everyone is a cunt sometimes. Men are mostly motherfuckers. For someone who has spent most of his life evading capture—by the poverty of his youth, the gang violence of his adolescence, sexual prejudice, AIDS, house fires, the housing market, you name it—the overdue interest in his work has much to do with a refusal to be caught under certain labels. Labels make it easier to categorize, and, more importantly, fund certain forms of art making. Who gets invited to the Latino group show? “We’ve always been here,” Rivera says. “We’ve been part of everything that’s happened—not just in the city—but art in general. But somehow, we get put into our own little category. We say we want to sit at the table. We never said the table was ‘How to be Latino!’”

“I took people that were ordinarily considered freaky and made them look amazing, or cool, or normal. My gig was to have people look the way they wanted to look.”

Rivera’s work isn’t at the Latino table. It’s not even in the same restaurant. It’s down the street taking a smoke break in a piss-stained alley behind Mugy’s, where inside the owner, Yoshi, is stomping the stage in a flamenco dress while singing in Japanese. Rivera was included in the Hammer Museum’s biennial Made in L.A. 2020: a version. Last summer, he began preparing for a solo exhibition at Reena Spaulings Fine Art, in New York, and working with an editor to expand the video he created for the Hammer Museum into a longer film “to submit to festivals and shit.” The exposure of Rivera’s work dovetails with interest in photographers such as Sunil Gupta and Alvin Baltrop, who documented ways of life that complicate the aesthetic and historical narratives set by the canon of white street photographers including Diane Arbus and Garry Winogrand. The people in Rivera’s photographs are complicated, glamorous, louche. And while Rivera is quite deliberate about the cinematic qualities of his images, they contain the layered ambiguity of a Manet painting. Tolerance of ambiguity in our cultural products is the necessary precursor to appreciate his work. Loving ambiguity is how to see yourself in these pictures, however unfabulous you may be in life.

And yet, his story already has the signs of apocrypha, the constellation of anecdotes that settles into shape around an artist as they become part of art history: a history laid out lovingly and neatly (as much as is possible) by the writer Chris Kraus in a monograph published by Semiotext(e) in 2020. The book, named after her essay, is titled Provisional Notes for a Disappeared City. In addition to Kraus’s introduction, there’s a dizzying stream-of-consciousness text by Rivera himself, set apart by pastel peach matte paper inserted in the middle of the book, like how in the Bible the words thought to come directly from Jesus are printed in red. There’s a biography of Tatiana Volty, one of the drag queens in the book, written by the writer Luis Bauz, and a protracted email exchange between Rivera and Vaginal Davis, another artist who exploded genres and labels, mainly through her punk performances and bands and writing. Rivera captured portraits of her before she moved to Berlin in 2006, and their volley of anecdotes is rhetorical sport of the highest, most shit- talking order.

Many of the drag performers and club goers in Los Angeles chronicled by Rivera are no longer around, succumbing either to drugs or AIDS or violence, but some aspects of his city still concatenate into the present. Rita Gonzalez, currently head of contemporary art at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, is caught looking cute and puckish at a house party in the 1990s. Miss Alex, the drag performer who helped Rivera get backstage access to many of the drag bars around LA, where he captured some of his most intimate scenes, died of a stroke at the same county hospital where I had often sat on the floor, waiting six, eight hours to see a doctor when I didn’t have insurance. When I lived in Echo Park in the early 2000s, it was on the same block on Laveta Terrace that Rivera lived on nearly twenty years earlier. Little Joy was still a bit of a shithole then, allowing seventeen- year-old me to drink, and where I’ve known a friend or two to be stabbed. Rivera shows me a picture of a drag queen in a butterfly mask crawling on the pool table there, serving equal parts Mardi Gras and Moulin Rouge in the dingy bar at the foot of Dodger Stadium.

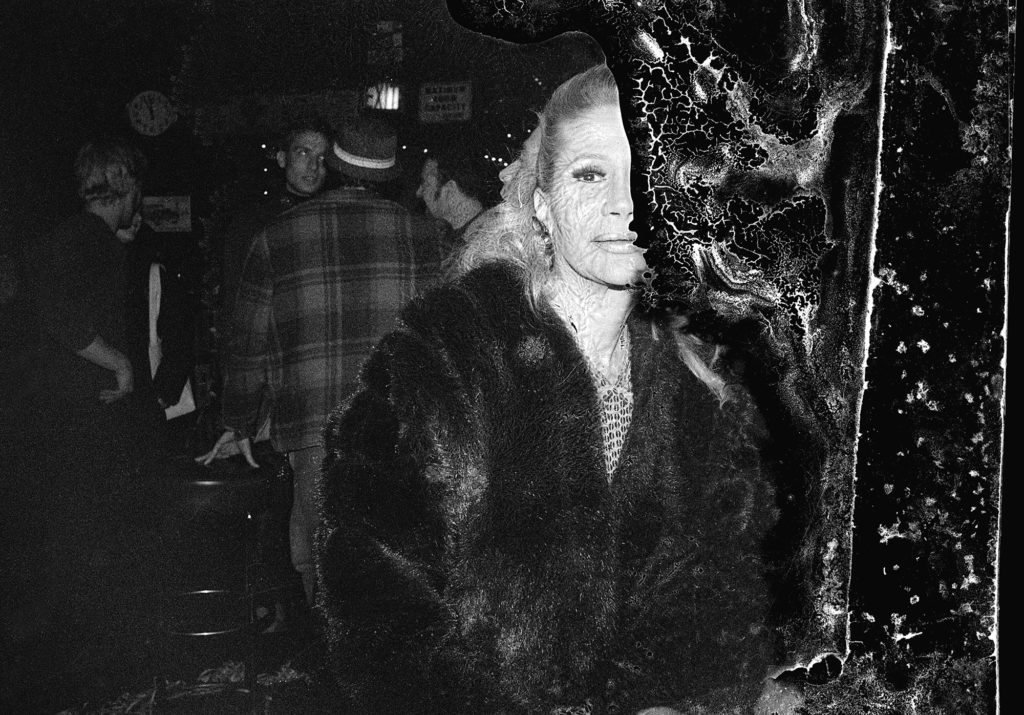

He shows me more ruined prints: “These were from the other fire.” The one that happened in 2012 and nearly took out his current home. The origins of that fire are less theatrical, more apropos to the life Rivera lives now with his husband and their dog, Coco, surrounded by his work and the books and records that inspire it. Roofers accidentally set the entire attic—where Rivera’s negatives are stored—aflame while sealing roofing tar with a torch. The pressure from the blast of the fire department’s hoses caused more damage than the fire itself, resulting in a strange body of compromised negatives that Rivera has been printing nonetheless. They look otherworldly.

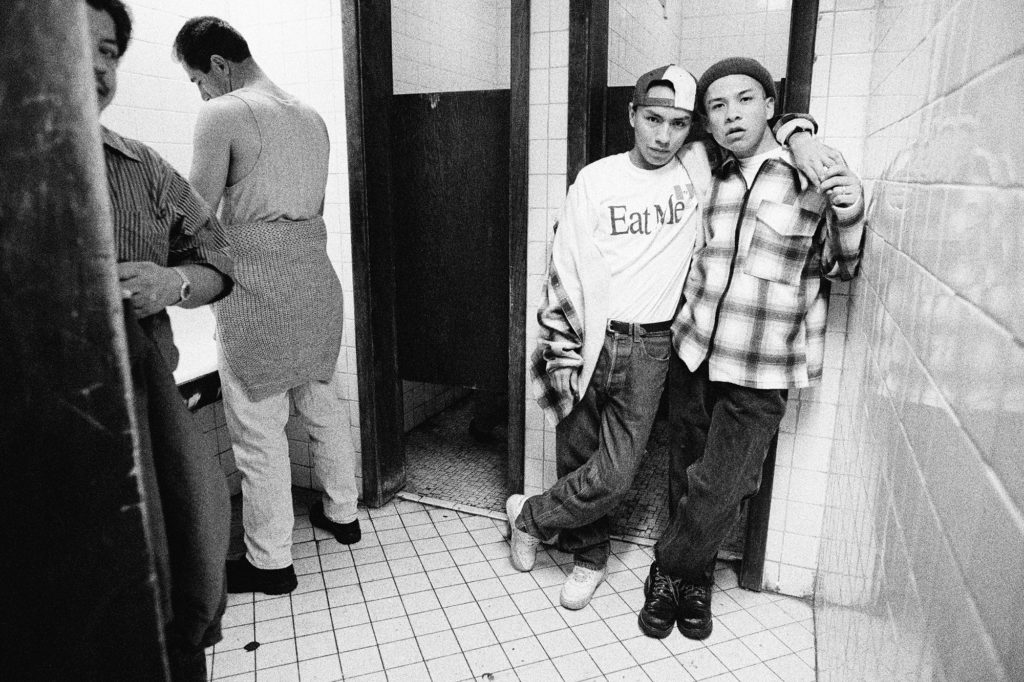

“This was unpublished until I posted it on Instagram, then Hedi saw it, and he’s going to use it for a book cover,” Rivera says, referring to Semiotext(e)’s editor Hedi El Kholti. All that’s legible from what appears to be a house-party scene is the plaid-clad boy on the right, casually leaning against the cabinetry in what might be a kitchen. To the left, a T-shirt and an arm extend downward from the central bloom of damage that makes up the majority of the frame. It spills out like rot, like lungs, like a coral reef, like lava or dried mushrooms, the kind that get you high. These “ruined” photographs feel oddly fitting—to Rivera, to the intensity of the times he lived in, to the fragile and ever-shifting nature of what he documented. “These are definitely more creative,” he laughs. “The water and the heat did something very specific to them. It took a mélange of misfortunes to create these.”

All photographs courtesy the artist and Reena Spaulings Fine Art, New York/Los Angeles

It’s hard to square the sensitive aspects of Rivera, who refers to his camera as a “saving grace” from a chaotic and violent childhood, with the lucid confidence with which he talks about his work. “I used to always be compared to what’s-her-name”— Nan Goldin—“or Diane Arbus. We’re completely different. When you look at her shit, I don’t know . . .” He spreads his arms out wide, reifying the spiritual and emotional distance Arbus kept from her subjects, “. . . it felt like you were excluded. Like you’re not invited to that party. My work is not like that at all. She took people that were normal and made them look freaky. I took people that were ordinarily considered freaky and made them look amazing, or cool, or normal. My gig was to have people look the way they wanted to look.”

Some histories do not spool out in a straight line, they explode like confetti left on the ground after a party. A book is one way to do it, so is an exhibition, or a film, all enterprises Rivera has in the works. But words and pictures can’t hold everything that has happened. “Originally the book was more of an homage to these girls than anything else. That’s why I thought it was important to have these texts in here, to give meaning to all this stuff, to connect the dots.” Often what is recovered can only point toward what is lost. “I’m such a cunt,” he says, anytime he struggles to recall a detail. Names and stories fall out of his mouth like glitter, and some are beginning to escape him. To wrangle them is like stuffing a kaleidoscope. The pieces are all there, no one is missing, it’s just that the image never sits still. It will always change depending on how you hold it and from where you look. It’s the aftermath of a party that may be over, but you’re still invited. That has always been the subtext of these images, lit up and brought to life by the third and final fire, Rivera himself.

This piece originally appeared in Aperture, issue 245, “Latinx,” under the title “Reynaldo Rivera: Glitter for the Fire.”