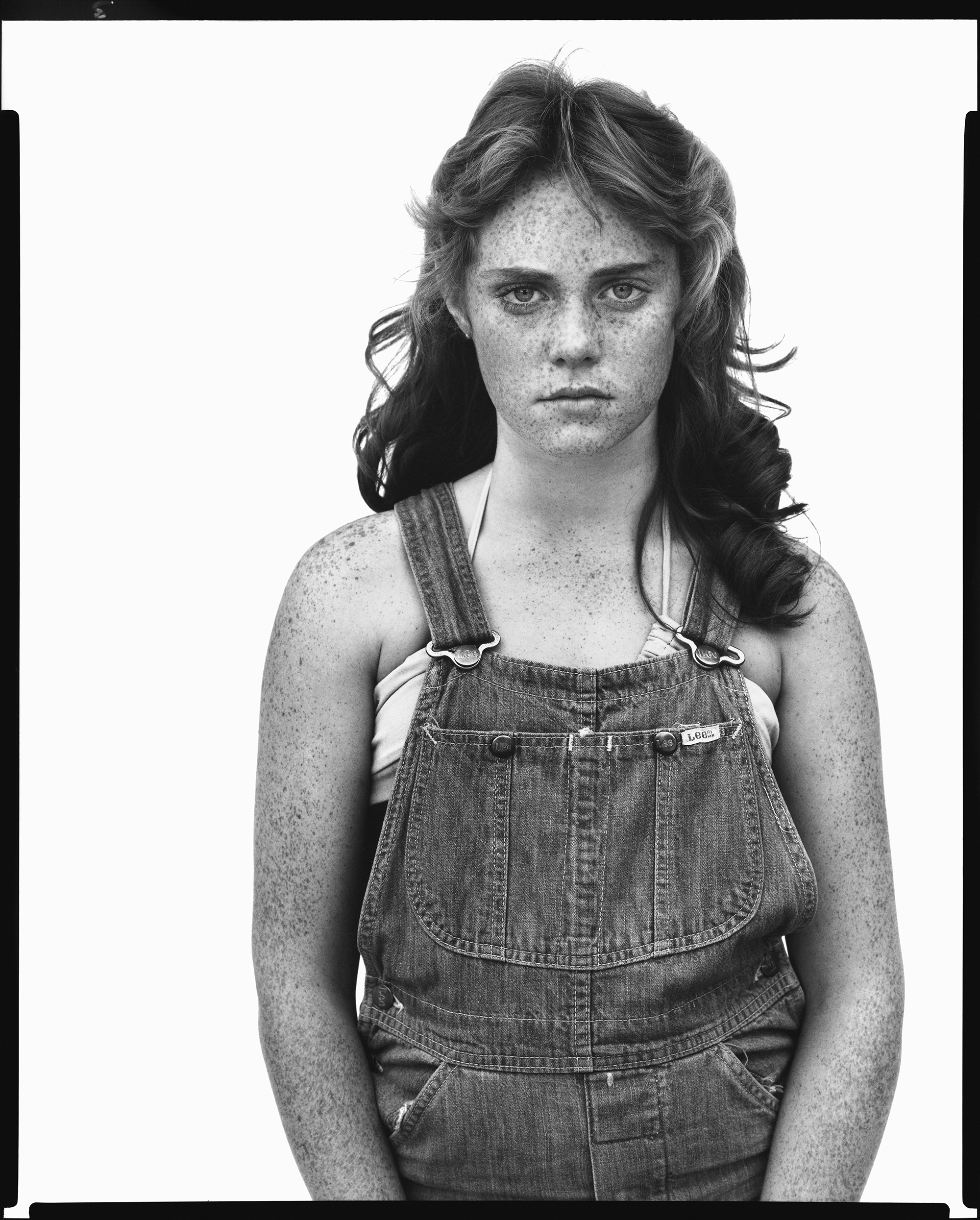

Richard Avedon, Sandra Bennett, twelve year old, Rocky Ford, Colorado, August 23, 1980

By the late 1970s, Richard Avedon was known as the preeminent fashion photographer, the master whose pictures appeared on almost every single cover of Vogue, who brought Brooke Shields into the limelight, who captured a normally shimmery and ebullient Marilyn Monroe looking unusually forlorn, and whose technicolor photos of the Beatles for Look Magazine were tacked on the walls of thousands of teenage girls’ bedrooms.

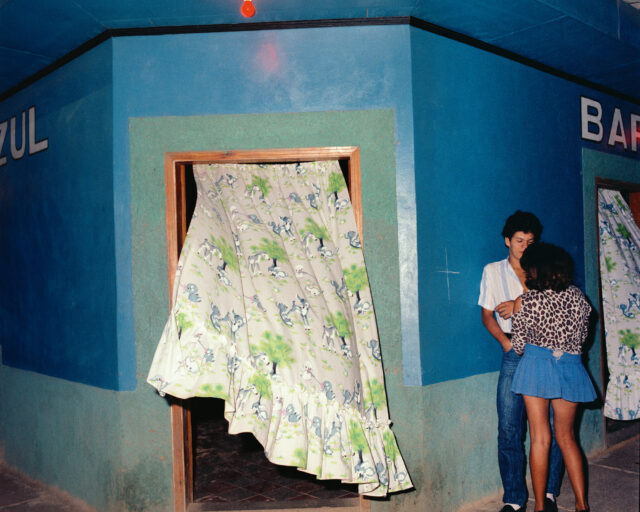

Yet it was a photograph of a different nature that caught the eye of Mitchell A. Wilder, the founding director of the Amon Carter Museum in Fort Worth, Texas: a modest portrait Avedon made of a ranch hand in Montana in 1978. Wilder called Avedon and proposed that, with the museum’s assistance, Avedon continue photographing the people of the West, culminating in an exhibition. It was perhaps shocking to some, when the resultant exhibition and book In the American West appeared in 1985, that a glamorous New Yorker would take on such a rugged project, and critics were disdainful of what they perceived as an improper portrait of America. “This is not the vanishing West, all perfumed and riding into the sunset,” a Los Angeles Times critic wrote of the show’s opening. “It’s the unsavory West that’s with us.”

On the fortieth anniversary of the exhibition, Abrams is reissuing the publication, and the Fondation Cartier-Bresson in Paris is displaying all 110 of the original images from the book, in a presentation curated by Clément Chéroux. The portraits from In the American West may not be romantic images—no pomp and circumstance—but they are dignified. Coal miners, cotton farmers, and cowboys stand tall and proud. Avedon worked quickly, street-casting his subjects alongside his assistant Laura Wilson, setting up white paper backdrops and shooting instinctively. Post-production was another matter entirely: Chéroux’s exhibition showcases the meticulous care that went into each print, with Avedon’s instructions for dodging and burning scrawled across pictures. I recently sat down with Chéroux to discuss the enduring legacy of Avedon’s West, and its documentary value.

Christina Cacouris: In the opening to In the American West, Richard Avedon wrote that all photographs are accurate, but none of them are the truth. I was trying to parse if he means that photography generally is just a simulacrum of reality; if there is no such thing as true documentary photography. As the Director of the Cartier-Bresson Foundation, how do you interpret that statement?

Clément Chéroux: I think that every photograph has documentary value even if it’s a photograph that was set up and that was made as a work of fiction, and this is exactly what Avedon was interested in doing. When the show opened in 1985, he started a few interviews by saying this is a fiction, there is no more truth in my photographs than in the Western films of John Wayne. Most of these photographs were made with the desire to make a statement about the United States in the beginning of the 1980s. But Avedon was clear about the fact that the photographs were not necessarily the truth; they were an interpretation from his point of view about America at that time. It still has a documentary value, but I don’t think that he ever thought of this project as representing the truth of the United States.

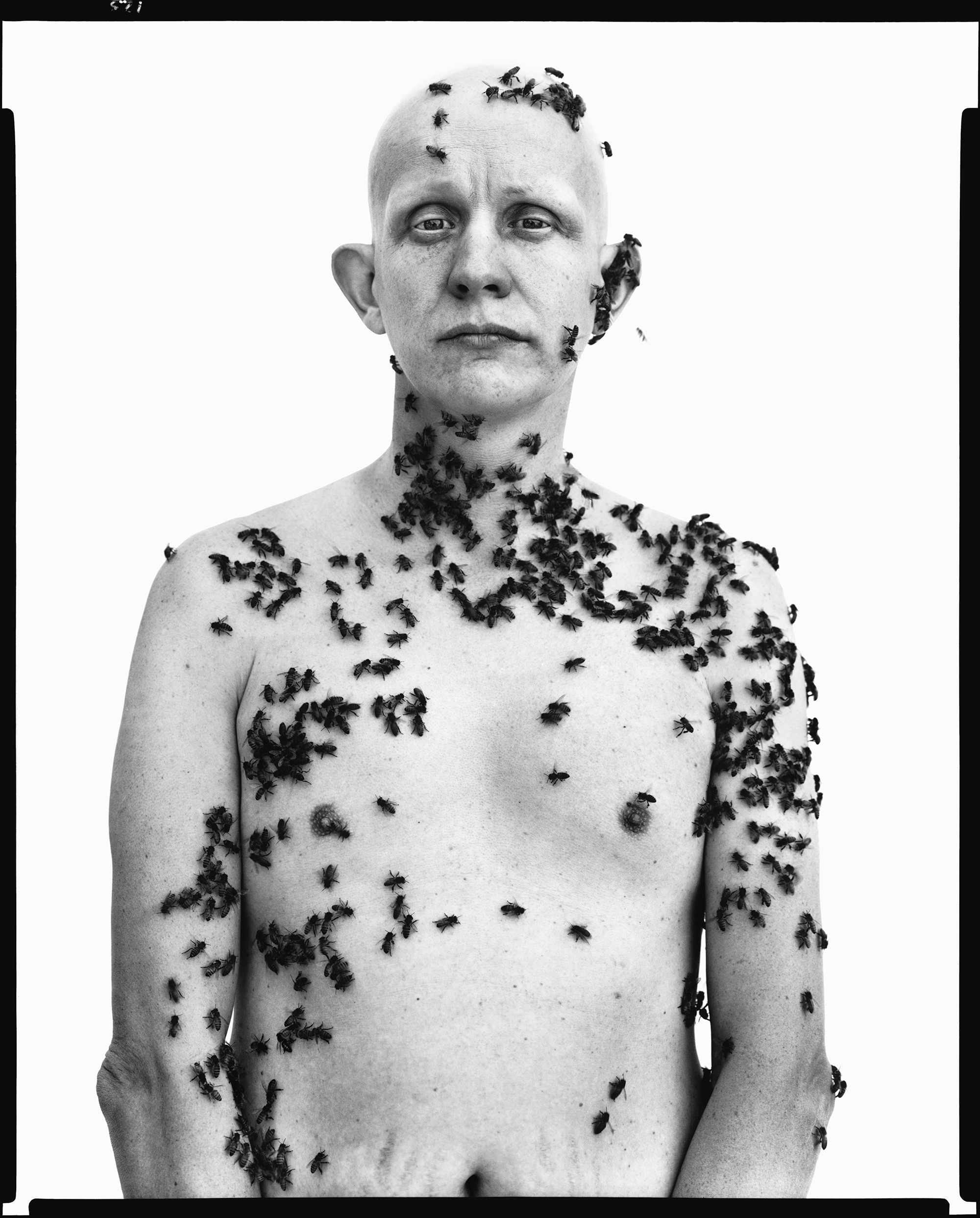

The subjective part of the project is clear. And most of the photographs were from encounters where he photographed people he met as they were. He also stated very clearly that a few photographs were set up, and the photograph of the Bee Man is a good example of that. He first published an advertisement in the American Bee Journal to find the type of person he was interested in—we have the advertisement in the exhibition, we found the original magazine where it was published. So, he looked for that person and made some drawings in preparation for the shoot. He clearly had a dream of a specific image that he wanted to realize. And he made clear that he wanted to have this photograph to show the subjective part of the project, that it was not exclusively a documentary project. I think the Bee Man shows us that there isn’t truth on one side and fiction on the other. It’s much more complex.

Cacouris: I love that you get to see so much of the behind the scenes in the way that you’ve staged this exhibition, especially with the bee photograph. It was also really valuable to see all these preparatory Polaroids; there were quite a few where people were smiling and excited, but you don’t really feel that sentiment within the final images, which goes back to what you’re saying about how he had a very specific image in mind when shooting. Why was it important to you to show all of the preparation?

Chéroux: Two reasons; the first one is that I was interested in reminding visitors to the exhibition that there is someone behind each photograph. And by introducing some letters, some Polaroids, it was a good way to remind the visitors that a human being is behind all of these. But it can easily become very anecdotal to have all these stories behind each image, so I tried to find a way to give some information but not have it systematically throughout the exhibition. I was also interested in helping the public to understand the work that goes into each photograph and the way that Avedon was transforming someone he was encountering into a subject. If you compare some of these Polaroids with the final results, you can clearly see that there is a lot of work behind the image: it’s not only the photographic skill, it’s not only the white background, the light, the framing, the composition of the image, it’s also something that happened during the shoot.

We have some testimonies about the way that Avedon was working, and we know that he was not behind his camera, he was standing next to it. He had a strong connection with his subjects, mimicking their position, and asking them to respond to a very small gesture by showing himself moving in one direction or another, and I think a lot of the work is in this relationship that he was establishing with the subject. Photographic literature usually focuses on the framing, the composition, but for me, this kind of interaction he was able to develop with the subject is where the work is, where he’s transforming the people that he met into a Richard Avedon photograph.

Cacouris: In the foreword to the book, he is very clear about what type of camera he uses, the exact size of the paper that he’s using, how he photographed in shade or natural light and how he achieved the final pictures. But even armed with that knowledge, nobody would be able to recreate any of this work because there’s something ineffable about the way that he related to people and the way that created these images. Do you recall the first time you encountered In the American West?

Chéroux: I first looked at the book in the 1990s, and I was very impressed by the development of the whole project. So, when I was developing this exhibition, I was interested in showing the entire group of photographs, not only the icons. I was also interested in showing the reference set that he had been using for printing the book. When we were working on preparing the exhibition, I tried different things; I tried to have a different kind of organization of the whole group of photographs, and of course it didn’t work at all. After a few hours of working, it was clear that we had to respect the layout of the book, and so we chose very quickly to start with the first image of the book and to end with the last image. We found a way to respect the rhythm of the book—when there is a white page, there is a space on the wall equivalent to the size of a frame. If you step back and have a look at the wall, you clearly see that he and Marvin Israel had been working on the layout very carefully and that they are playing with rhythm, with the size of the body in the frame, with the tonality of the image. Just before the Bee Man, we have the coal miners, these very strong dark images and then suddenly you have the white body of Ronald Fisher with all these little bees. We wanted to respect this in the exhibition, the sense that it was not just a collection of twentieth-century photographs of Americans, but it was a group of images, a full sentence.

Cacouris: You mentioned that he knew that the work would be a bit divisive and that that may have been part of the intention. I was reading a New York Times review from 1985, where they compared his work to what Ansel Adams had done in the West, showing it as this majestic landscape versus the way that Avedon has depicted it, what they described as hell broken open.

Chéroux: The response at the time was quite critical. It’s clear that it did not correspond to the idea that a lot of Americans had of their country at the time. In the ’80s, shows like Dallas or Dynasty were on TV showing an America with a lot of success and money, and Richard Avedon clearly chose to show the other side of that. When the project was launched, a lot of journalists assumed that Avedon was fed up with the elite or was bored of photographing beautiful people, but I truly believe that it was not the case. If you look at the development of Avedon’s career, you can clearly see that he was interested in making a statement about the social and political climate of the US, like his project with James Baldwin in the ’60s about the civil rights movement.

I believe that his interest here was not about just showing the dark side of America. He was much more interested in making a statement in a moment that was a very difficult moment for America, after all these oil crises from the ’70’s, the free market capitalism of the Reagan government, there was a lot of deindustrialization, people losing their jobs and going under the poverty line. The first image in the book is an unemployed person. It was a political statement from Richard Avedon. And of course, this was not well received. It was heavily criticized, especially coming from someone who was one of the highest paid photographers of the time. A few critics were also saying that he was exploiting his subjects, which is not true; he was paying them. He was not just stealing an image. He was really spending time with his subjects, having conversation with them, not just taking a photograph and leaving. He tried to help some of them. He really had a relationship with the people that he was photographing.

All photographs © The Richard Avedon Foundation

Cacouris: When I was looking through the show and through the book, one of the images that really stuck with me most is a woman from a mental hospital; her hand is moving and it’s, I think, the only image where there is a blur. And that one really struck me. There was something so powerful, and seeing the way that she’s looking outside of the camera, and there was something poignant captured in it. I’m curious if there are any images in particular that stick with you more than others or ones that have especially gripped you.

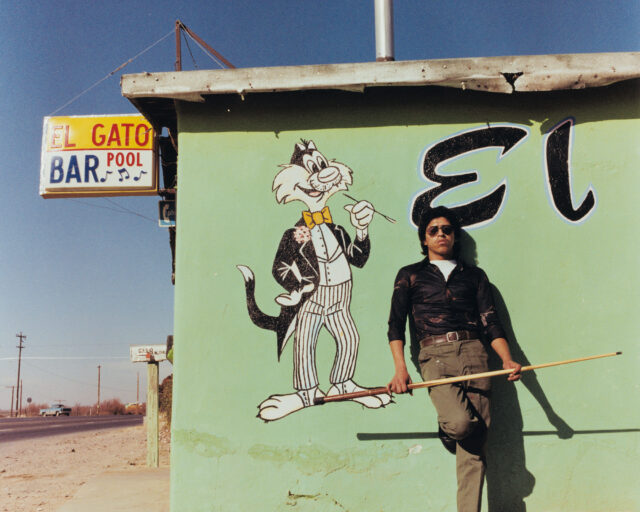

Chéroux: Every time I look at the book I find something new; this is part of the pleasure of curating such a project. You establish a strong relationship with some of these images. You discover some new details. So, I hope visitors will go beyond the famous photographs and have encounters like Avedon had during his journey through the West. There’s an amazing photograph of Juan Patricio Lobato, a carnie. We are exhibiting a letter that we found in the Avedon Foundation archives from a woman who clearly fell in love with Juan from seeing him in the book. The letter is amazing: she writes, “I bought your book, I saw this photograph, and this is something that happens only once in a lifetime, that you meet someone.” But she’s not asking to meet with the guy. She’s not asking for his address. She is asking for other photographs. She wants more. She’s trying to explain what she felt in front of that photograph; there was clearly an encounter between a viewer and the subject of a photograph. That letter shows the power of photography. I truly hope that people will make more encounters like this one.

Richard Avedon: In the American West is on view at the Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson, Paris, through October 12, 2025.