Rineke Dijkstra’s Captivating Videos Portray the Gestures of Youth

In the exhibition “I See You,” the photographer’s work is a study of self-presentation, showing how the camera can be an interlocutor.

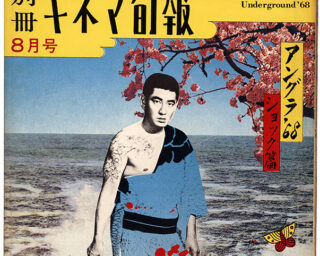

Still from Rineke Dijkstra, Anna, The Gymschool, 2014

A young ballerina attempts to perfect a dance routine, a schoolgirl draws an artwork, gymnasts practice exercises: the Dutch artist Rineke Dijkstra is masterful at filming her models so the viewer never forgets that her sitters know they are being watched. In Dijkstra’s well-known photographic portraits, this is obvious because her subjects look directly at the camera. In her videos, though, they rarely do—unless their gaze crosses it because of their movements. Still, the models in Dijkstra’s videos act as if they are keenly aware of the camera’s presence, without ever being theatrical. I See You, Dijkstra’s current exhibition at the Maison Européenne de la Photographie (MEP) in Paris, highlights this aspect of her work, displaying four video projections alongside a few supplementary photographs, all of which depict the actions of mostly girls: ballerinas, gymnasts, and schoolchildren. Each work is a study of self-presentation where the camera is an interlocutor. In these videos, Dijkstra’s models command attention by showing the viewer what they are capable of, whether it is a particular skill, the completion of a task, or an opinion of an artwork. Their absorption possesses the same presence that the outward-looking subjects of Dijkstra’s photographs have.

Known for her portraits of adolescents and young adults, Dijkstra, who has exhibited for over thirty years, has been the subject of major solo retrospectives at museums such as Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum, the Guggenheim Museum in New York, and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Unlike in the works of other contemporary photographers such as Collier Schorr or Roe Ethridge that incorporate the language of advertising, Dijkstra’s synthesis, a result of her starting out as a commercial photographer, is at first less easy to spot. Her best-known work is a series of teenagers at beaches (in Poland, Ukraine, Croatia, and the US), in which she merges two different approaches to portraiture: traditional studies of specific individuals with the more sociological samples of populations. Influenced equally by August Sander and Diane Arbus, her work exhibits a productive tension between her early commercial training and the fine-art documentary tradition.

Dijkstra simultaneously makes the camera feel neutral and active, a tool through which her subjects are encouraged to present themselves.

Dijkstra has stated on many occasions that she gives her models minimal direction, wanting to let them present themselves naturally. And yet, not everyone could manage to elicit such personality or ease out of her models. In the video Ruth Drawing Picasso (2009), for example, a nine-year-old girl sits on a museum floor sketching the modernist painter’s infamous The Weeping Woman (1937). For all six minutes, the camera remains at floor level, focused on Ruth as she attempts to recreate the painting. She concentrates, she sketches, she hums and haws, she passes a crayon to a classmate sitting on the floor just outside of the frame. Much of this young girl’s willful character comes through in the faces she makes while she works; as the video began to cycle through one complete screening, I found myself smiling because of how charming she is. At a certain point, though, I wondered if her completely natural-looking concentration came from knowing she was being filmed. “Life,” writes the French filmmaker Robert Bresson, “cannot be rendered by photographic recopying of life, but by secret laws in the midst of which you can feel your models moving.” Instead of making a portrait feel less natural, awareness from the model becomes a vessel through which their character is transmitted. In a playful gesture, Ruth’s drawing of The Weeping Woman is displayed in a vitrine in the museum’s hallway adjacent to the screening room. It is titled, dated, signed, and dedicated: “For Rineke.”

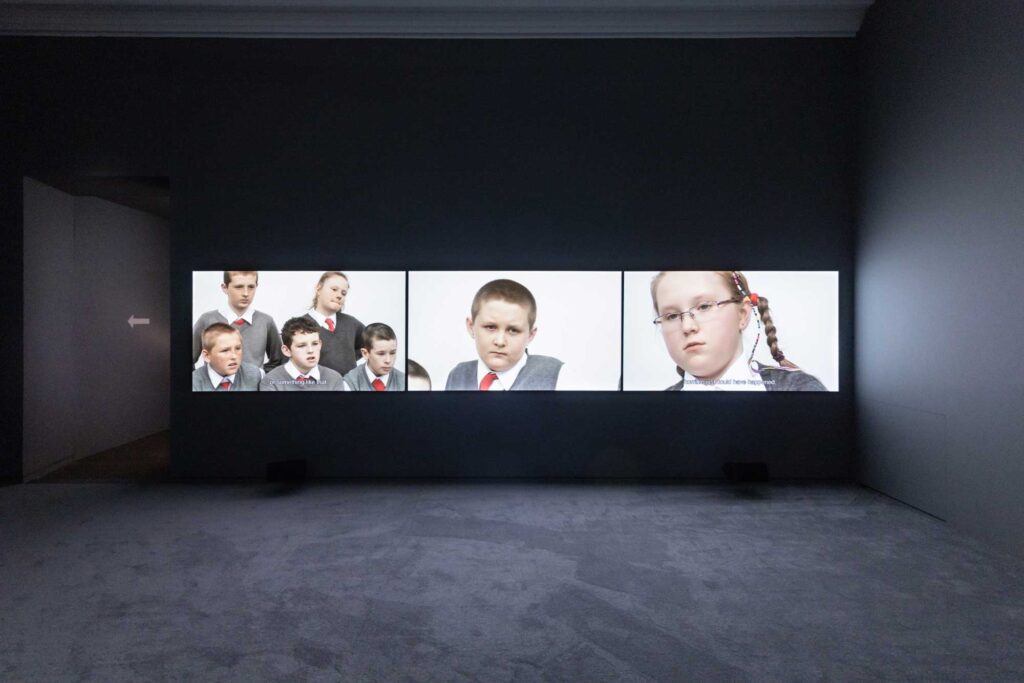

In I See a Woman Crying (Weeping Woman) (2009), a three-channel video that forms a sort of diptych with Ruth, a mixed group of schoolchildren wearing the same uniforms look at Picasso’s Weeping Woman, which is again outside of Dijkstra’s frame. The children describe the painting and discuss what they think it is about: what has happened to her, why she is crying. The responses, which range from projections of trouble at home to fantasies about video games and money, are charming, hilarious, and sometimes heartbreaking. It becomes a sort of collective work of criticism on the infamous portrait of Dora Maar from the perspective of children from northern England, and they clearly enjoy giving their opinions.

Their ease seems to come from Dijkstra’s filming method. She simultaneously makes the camera feel neutral and active, a tool through which her subjects are encouraged to present themselves. She creates an awareness, a certain visual reciprocity, between the viewer and model. There are little to no religious connotations in Dijkstra’s work, particularly non-Western ones, but while watching the videos, I couldn’t help but think of the Sanskrit word darshan. The word can translate very simply as “worship.” More literally, it means “glimpse” or “view,” implying visual interrelatedness between the human and the divine, and a sense of simultaneously seeing and being seen. Dijkstra’s models hold themselves in a way that manifests a secular version of this concept. Each model behaves as if they believe they can transmit themselves through the camera, not simply be captured by it.

The final two of the works that visitors encounter in I See You, Marianna (The Fairy Doll) and The Gymschool, were originally produced for Manifesta in 2014, the year the biennial took place in St. Petersburg. (Watching these works within the context of the ongoing invasion of Ukraine by Russian forces feels both unsettling and poignant, particularly because Dijkstra also shot in Ukraine in the 1990s.) In Marianna, a young ballerina practices The Fairy Doll, taking instructions from her off-camera teacher. As the instructor drills her further and further, for nearly twenty minutes, the girl maintains her resolve and concentration, although as the video reaches its end, she clearly attempts to ward off strain or even frustration from appearing on her face. In the accompanying photograph, the only large-scale one in the exhibition, Marianna and Sasha, Kingisepp, Russia, November 2, 2014, the ballerina and her instructor look directly at the camera, the former maintaining her poise and determination. This leads to a hallway with smaller-scale photographs of gymnasts, which introduce a video in the next room. Each figure is in mid-pose, their eyes capturing those of the viewer.

All works courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery, Paris and New York

In Gymschool, the final three-channel video, a cohort of young girls at the Zhemchuzhina Olympic School in St. Petersburg practice a particularly Russian form of training that combines gymnastics, body contortion, and ballet. The girls, ages eight to twelve, present a range of accomplishment. At the beginning of the video, the younger ones learn some of the routines, at times with an aid, such as a ball, while the older ones have mastered each of the body contortions and practice them effortlessly. While none of them look at the camera (as they do in the preceding photographs), they seem proud to display their accomplishments. As the video ends, the eldest gymnast completes a seemingly impossible contortion. Her gaze passes the camera and lands somewhere just beyond it. She smiles lightly.

Rineke Dijkstra — I See You is on view at MEP, Paris, through October 1, 2023.