Sable Elyse Smith, from Landscapes & Playgrounds (San Francisco: Sming Sming Books, 2017)

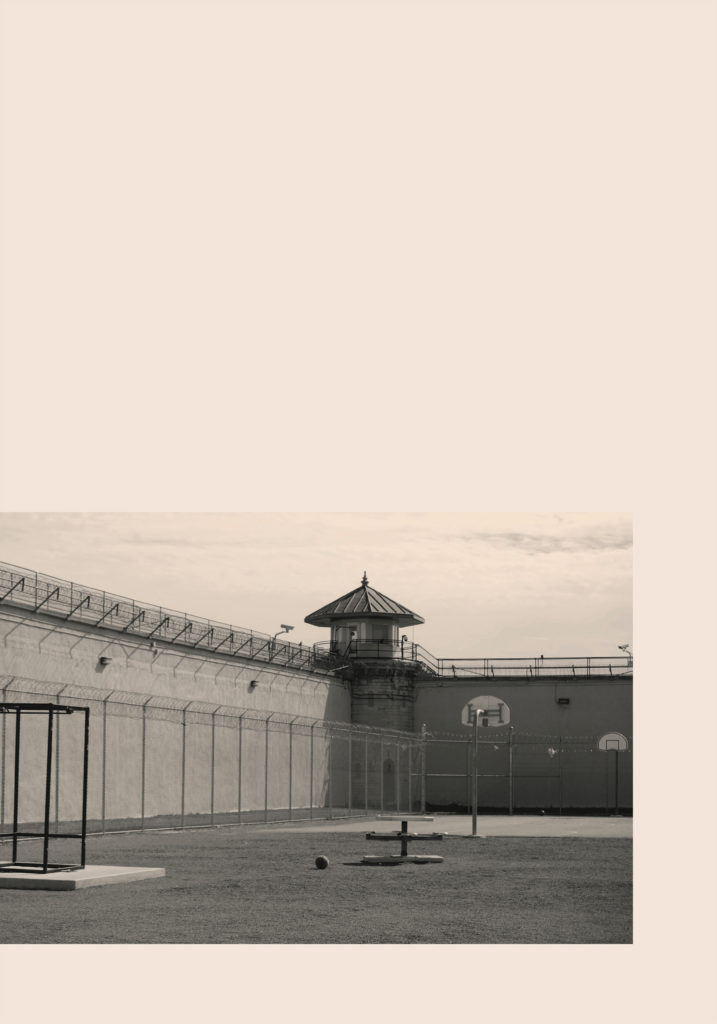

Landscapes & Playgrounds (2017), Sable Elyse Smith’s recent artist’s book, from which a sequence of pages is excerpted here, is a meditation on two sites of the prison environment after which the book takes its name. Within it, we encounter a world through the eyes of a young protagonist grappling with the prison system.

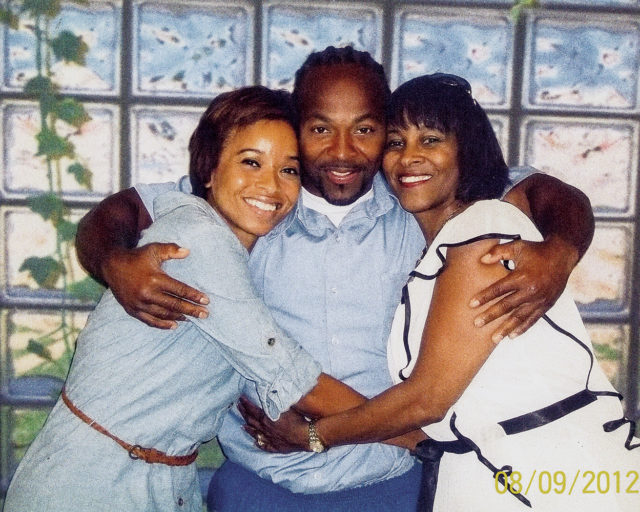

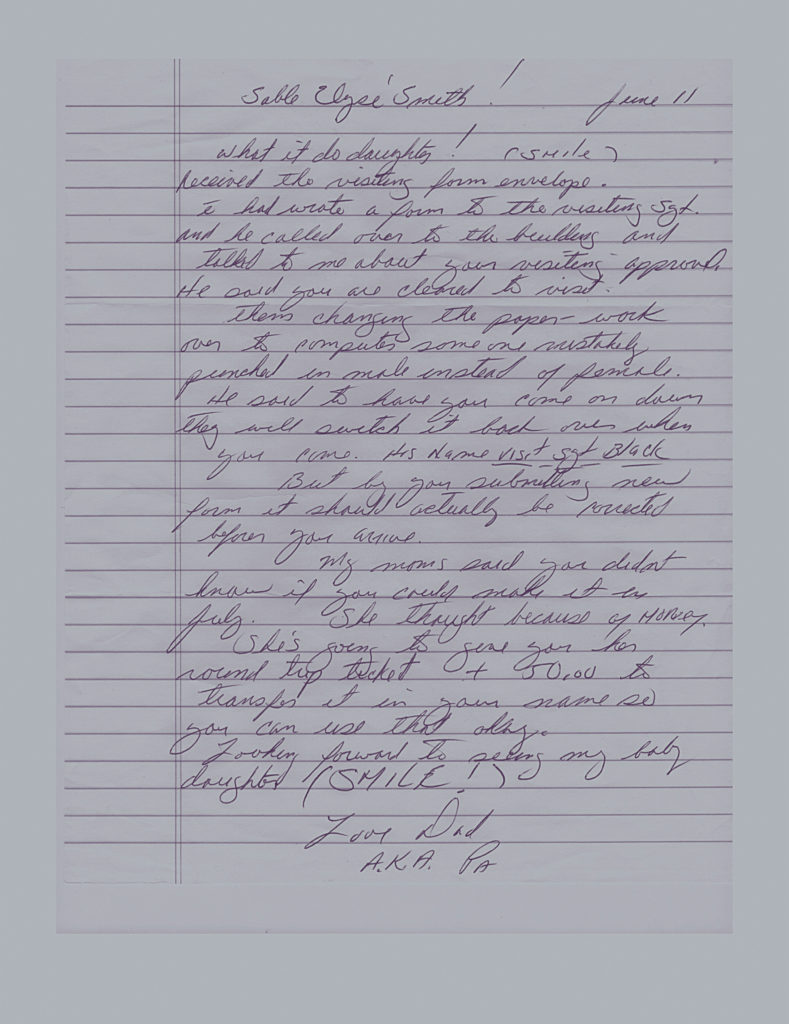

Smith, an artist working across video, poetry, and performance, is not merely interested in the cataclysmic consequences of mass incarceration that tend to be the focus of our justice dialogues in the United States. Landscapes & Playgrounds contains aerial images of prison architecture, surrounding land, and recreational areas such as basketball courts. But we also glimpse, through handwritten letters, the intimacy between an incarcerated father and a daughter that is not theirs alone, but one embedded in surveillance. Not all of the texts from these letters, written on crinkled lined paper, is visible, but the handwritten notes that we can read evoke a gentleness in their direct address. They often begin with a cheerful greeting like “What it do daughter!” and close with an equally heartfelt “Love you, Miss You. Pops. A.K.A. Pa.”

Still, the reader should resist a purely autobiographical read of Smith’s work. As she stated in the introduction to her recent exhibition Ordinary Violence (2017–18) at the Queens Museum, New York, “I am haunted by Trauma. We are woven into this kaleidoscopic memoir by our desires to consume pain, to blur fact and fiction, to escape.” Language becomes essential to Smith’s cartographical process, to her move away from the fact of her father’s incarceration while also drawing upon the truth of that experience. Amid a series of small photographs that are never quite center-aligned, some awash in hues of turquoise and beige, or overlaid with blocks of solid color, a refrain appears in white letters on a black ground, beginning: “We are a weird triangle of silence and smiles and pauses, of stepping backwards one foot after another after another until we’ve found the cold corner of a wall.” Here we, the readers, must also reckon with the interiority of the sentiment—the feel—that moves us closer to the minutiae of the protagonist’s visit.

Smith wades in the slippages between poetic language and family letters, between forensic photographic documents and tender snapshots. Rejecting concretized form, she probes the possibilities of the feel so that we might better understand the tactility of syntax and what it signifies through its materials and visions. “The images are made so that I can see the people in them,” Smith says of her practice. “So that I can see me.”

Courtesy the artist

This piece originally appeared in Aperture, issue 230, “Prison Nation.”