With Saul Leiter in the East Village

In memory of painter and photographer Saul Leiter, who recently passed away in New York City at the age of 89, Aperture republishes Eric Banks’s article about his visit with Leiter in his East Village studio. This article was published in the Fall 2013 issue of Aperture magazine.

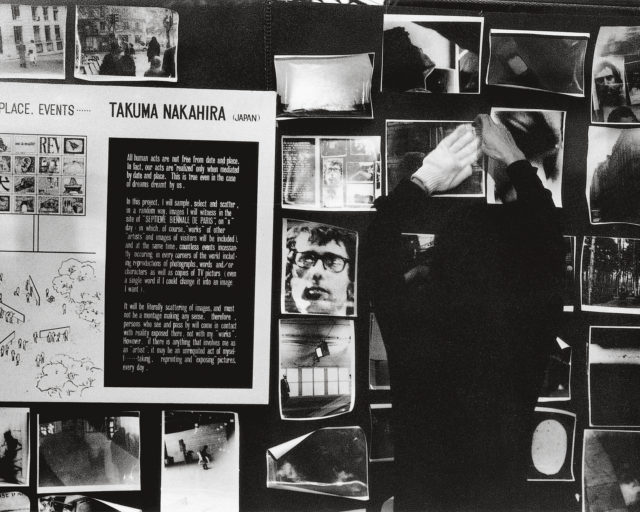

Views of Saul Leiter’s studio, with portrait of Leiter (center left), and paintings by Soames Bantry (top right), April 2013. Photographs by Jason Fulford.

The East Village block where Saul Leiter lives and works is a short walk from any number of reminders of what the neighborhood used to look like—the Strand Bookstore, the pierogi emporium Veselka. In mythic times this was a landscape hopping with artists who frequented the Cedar Tavern and the Club, among them Richard Pousette-Dart, who early on encouraged Leiter to continue his explorations with a camera. That is a distant memory in this stretch of the East Village, along the streets that Leiter famously photographed during that Ab-Ex decade, today in the shadow of the gleaming new towers that are monuments to Michael Bloomberg’s Gotham.

Once you’ve crossed the threshold of Leiter’s floor-through apartment, the dislocation between the now and the then is intensified. It’s a solidly New York space that gets a muted dose of sunlight on either end, but of a type that’s rarely so well preserved. It’s filled with a life’s work—paintings, stacks of books, knickknacks, odds and ends—but it seems more robustly lived in than cluttered. The hearsay about Leiter’s studio leads you to expect a hovel that would make the Collyer Brothers envious. Instead, there’s a kind of graceful accumulation that feels more like a painter’s garret than a packrat’s digs. Leiter does most of his work in the large room framed by a wall-size bay of windows overlooking a lovely little courtyard filled with cherry trees, yellow jonquils, and a gurgling fountain. If you forgot for the moment that you were in New York, you might believe you’d been transported to Paris.

Leiter has had ample time to accumulate. He moved into the building in 1952, six years after he arrived in New York via Cleveland from Pittsburgh, the son of a rabbi who didn’t approve of his ambition to be an artist. He took over the second-floor space in 2002, after the death of his longtime friend and partner, Soames Bantry, who had been there since 1960. (He now uses his original upstairs apartment as a second and more private studio as well as a storage space.) A number of Bantry’s quiet figurative canvases hang on the wall alongside a couple of Leiter’s own small-scale painted abstractions. His photographs, which belatedly won him recognition as a colorist far ahead of his time, are notably absent from the wall.

“Sometimes I think I love painting more than I do photography. But I love photography,” Leiter says, as we look through a small pile of brightly painted slabs of cardboard at his feet. “I wonder sometimes if I would have been a better painter if I had just been a painter. Would I have explored certain areas of painting? But what’s the point of thinking about it—if you do both, you do both. And sometimes I think you’re lucky if you do both.”

Painting remains Leiter’s touchstone, and our talk is filled with anecdotes about two of his great loves, Pierre Bonnard and Édouard Vuillard, as much as with stories of the New York School photographers he knew. A self-deprecating figure at eighty-nine, he is impatient with the story that has long been told about him: how the printing of the astonishing, lyrical color street scenes he shot mostly in the 1950s and early ’60s led to his rediscovery over the past two decades as a landmark figure in the history of New York photography. Leiter seems more bemused than angry over the opportunities he let pass by and ends most anecdotes with a rolling laugh that oddly reminds me of Buddy Hackett’s at the end of his jokes. His work was included in a group show at the Museum of Modern Art in 1953, but when he was invited to show in Edward Steichen’s 1955 Family of Man exhibition, he skipped it. He famously let other invitations pass by. “Some people have said to me: ‘I’ve never known anyone who has taken less advantage of so many opportunities.’ Someone wrote a letter to me in the ’70s inviting me to show in some exhibition in France, but I never opened the letter until this year. That’s not good. That’s not the way to advance a career.”

If it has not been an exemplary career trajectory, Leiter’s own path has led to the attention he is receiving now. An exhibition of his black-and-white and color work, as well as some of his paintings, organized by the Deichtorhallen in Hamburg, Germany, just toured the Kunsthaus Hundertwasser in Vienna, while an exhibition of his black-and-white work opened last month at Galerie 51 in Antwerp, Belgium. And in September, Steidl and Howard Greenberg Gallery—which hosted breakthrough shows of his early color work in 1995 and 2007—are co-publishing Early Black and White, a lavish two-volume monograph of work from the 1950s.

“People say now that I’m a pioneer. I don’t know how true that is. Kertész used color, Moholy-Nagy used color. There have always been artists who questioned the extreme use of color— Mary Cassatt thought Matisse was a complete faker. There has always been the thought that color is not as profound as the search for form. Maybe my work lacks structure, I don’t know?” And he laughs that Buddy Hackett laugh. “I’m mystified that anyone thinks liking color is a bad thing.”

As we look through a set of recently printed work in hushed tones, part of a series from 1948 to 1960 that Leiter is working on, I ask if he ever tired of shooting the area around the Village. He grins: “People think I made this story up, but I used to go the same breakfast place as Robert Frank, and he came in one day and said he was going back to Switzerland. I said, Why? He said there was nothing to photograph here. Then of course he did The Americans.

“I’d see something lying on the ground and take a picture of it, maybe because I was lazy.” When he was invited in the 1950s to project a group of his slides—images from what he calls his “garbage” series of “things flying in the street”—at the Club, he recalls that “someone vaguely thought that I had rearranged the stuff. He meant it as a kind of compliment, because they thought the arrangements were too good.”

The newly printed works are the perfect analogue of the uncanny sense of spatial and temporal dislocation in Leiter’s studio. In one of the photographs, I recognize the very skylight we’re looking through, though now much less clean, from 1960. His talent for capturing a little explosion of color through the reduced light of a smeary shop window or a sudden downpour is a constant. (“I do seem to have a weakness for red umbrellas,” he laughs.) In others, the humorously cropped bits of signage that Leiter captured while shooting from behind a storefront seem almost like a Conceptual photography joke avant la lettre. The scenes of street life are at once locally familiar but utterly foreign. I wonder if they strike him in the same way. “Sometimes I do something and I don’t take it too seriously, and then years later I look at it and it may be more interesting than I thought it was. If you take a picture of a row of cars in 1950, it’s a boring picture of a row of cars. But in 2013, you’re looking at antiques and objects that have a certain kind of something or other.”

Without missing a beat, he adds: “Sometimes I say time is on the side of the photographer.”

—

To read more about Saul Leiter’s life and work:

“Seeing Beauty With Saul Leiter” by Tony Cenicola (Lens)

“A Casual Conversation with Saul Leiter” (LightBox)