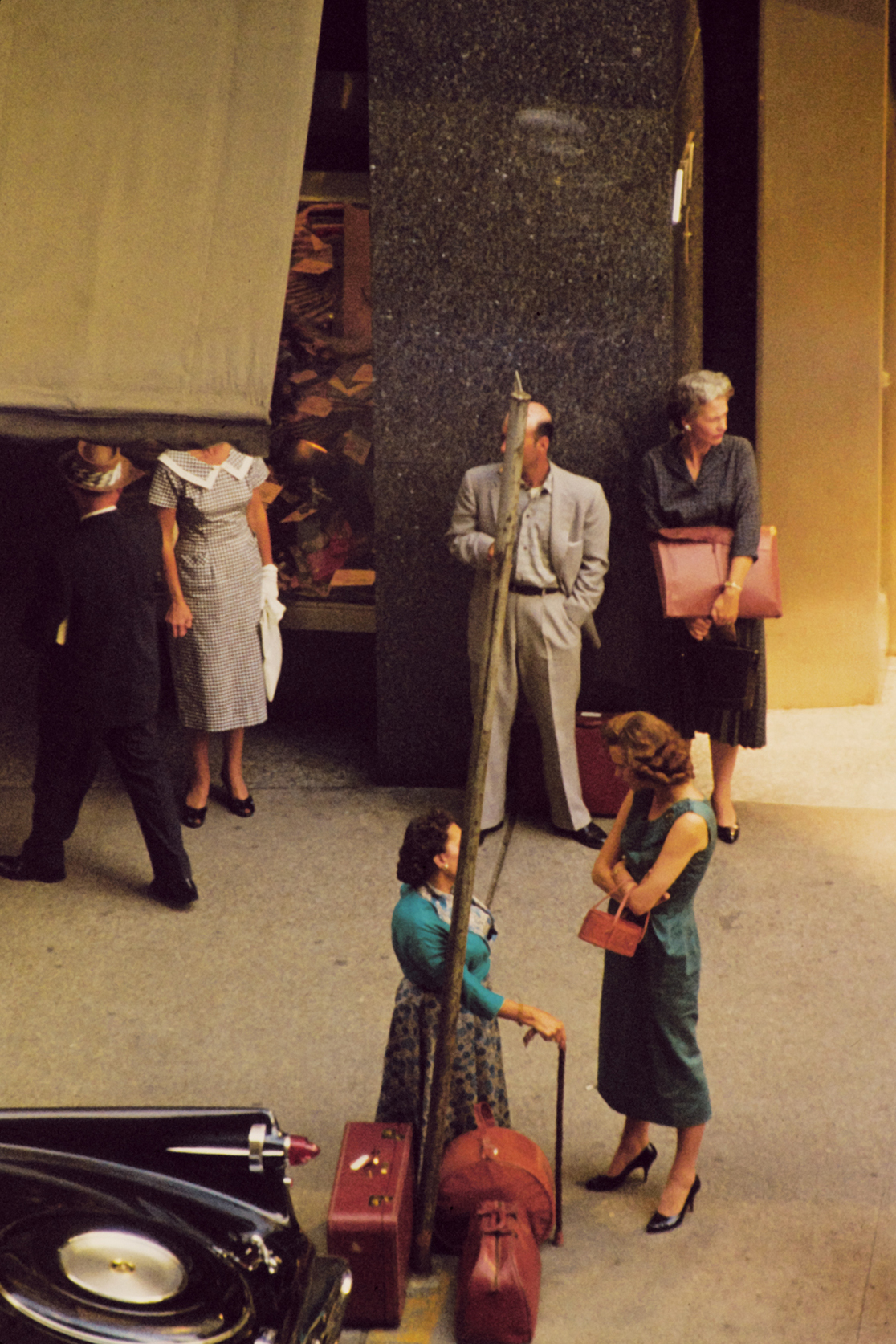

Saul Leiter, Untitled, early 1950s–1961

Among the great or later-to-be-great New York photographers of the middle of the last century, Saul Leiter bested them all in caring the least about fame or legacy.

“I wasn’t burdened by importance,” he said a few years before his death in 2013, synopsizing a devotion to unfettered autonomy that has itself come to shape his legacy. What his reticence meant, practically speaking, was that many thousands of the pictures he took over almost seven decades were never developed, printed, or seen during his lifetime, despite the fame that came thundering to his doorstep with the 2006 publication of Saul Leiter: Early Color. “Before he died, he said that what we had seen of his work was just the tip of the iceberg, and we’re really only now finding out what he meant,” said Michael Parillo, the associate director of the Saul Leiter Foundation, which has been hard at work to bring more of Leiter’s color photography into the world.

These previously unpublished selections of 35mm slides confirm and extend our sense of the stubborn singularity of Leiter’s color language. You might occasionally mistake a Stephen Shore for a William Eggleston or a Helen Levitt for an Evelyn Hofer, but it’s not easy to see a Leiter for anything else. His quietly elaborate layering of urban surfaces and his predilection for puncta such as red umbrellas, traffic lights, gently sloping car tops, and fractured window lettering are as instantly recognizable as a Giorgio Morandi bottle—as is Leiter’s enduring subject, the East Village neighborhood where he spent almost his entire adult life. Leiter wasn’t exactly a visual hermit; he took pictures in Paris and Rome, Brooklyn and Harlem. But his principal ambit was tightly and purposively bounded, the dozen or so blocks around his modest artist’s-garret apartment, streets he turned into the whole world, a photographer’s rendition of William Carlos Williams’s localist modernism.

It was a happy accident to see these unknown Leiter pictures for the first time last fall, during the run of Luigi Ghirri: The Idea of Building, a highly focused look at the work of the Italian photographer, organized by the painter Matt Connors at Matthew Marks Gallery. Connors writes that Ghirri, working from within Conceptualism, was “reading the physical world but also writing it,” making images that reassemble the built landscape recursively within the frame of the lens. Leiter, emerging from Abstract Expressionism, accomplished something strikingly similar on his own terms, rapidly and somehow instinctively on the street and then deliberatively in the editing, though he remained coy about his own considerable powers of stage management.

“I believe that there is something in you that strives for order and within that order there’s a certain kind of mishmashy confusion, and you bring this mishmashy confusion, if you succeed, into some kind of order,” he said. “There’s an element of control. There’s also an element that just kind of happens, if you’re very lucky.”

Leiter was the kind of artist who established the conditions for that luck, earning, as Emily Dickinson put it, “fortune’s expensive smile.”

Courtesy the Saul Leiter Foundation

This piece originally appeared in Aperture, issue 242, “New York.”