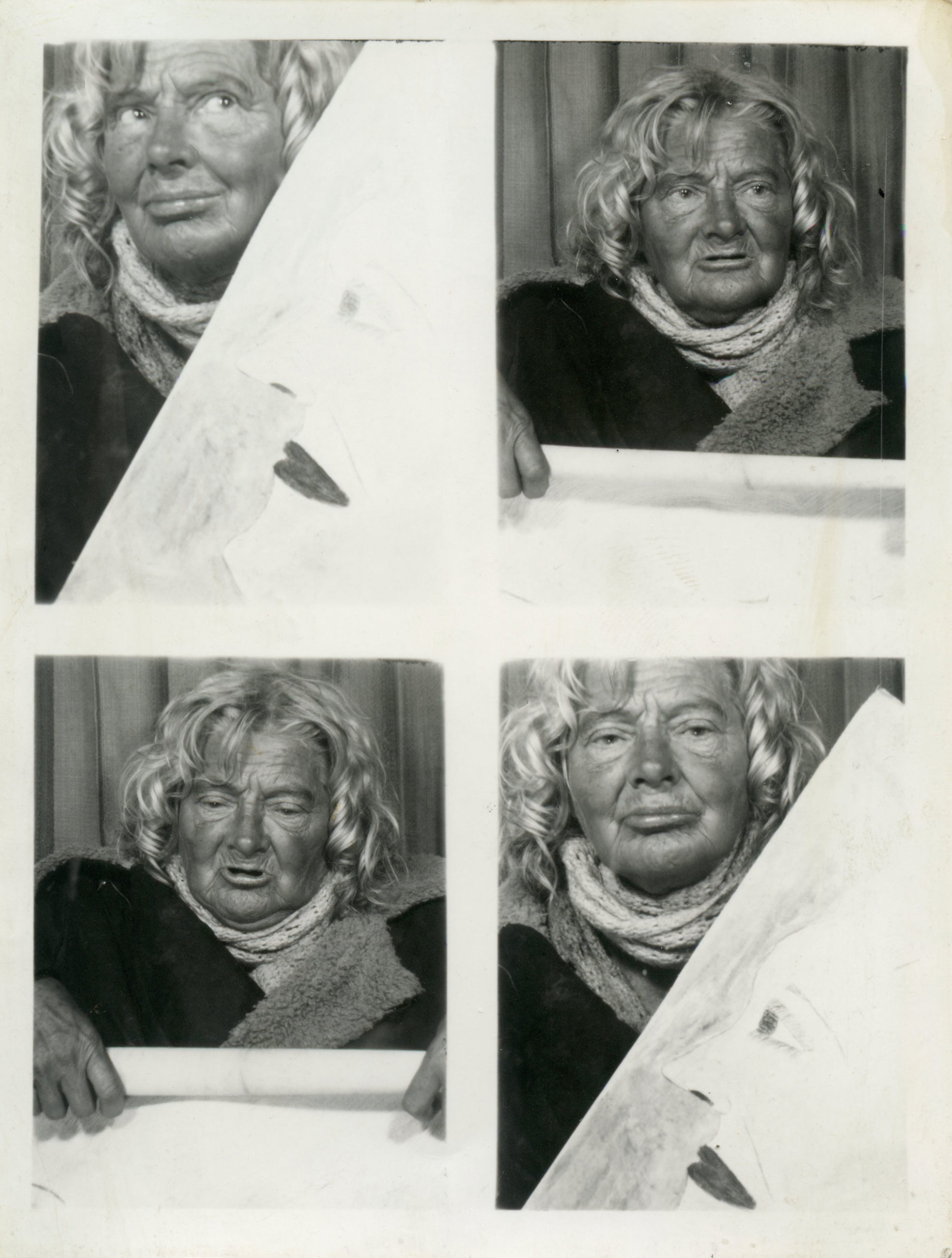

Lee Godie, Untitled, n.d.

Collection Bruno Decharme

Joseph Yoakum, the self-taught landscape artist who worked most of his life in Chicago, described his immanent, imagined panoramas as a “spiritual enfoldment.”

“What I don’t get,” he told a newspaper reporter in 1967, “God didn’t intend me to have.”

The list of artists who operated by much the same mechanism is long and extraordinary, many of them arrayed outside the confines of the art world proper: William Blake, Hilma af Klint, Madge Gill, Howard Finster, Frank Jones, Minnie Evans, probably Martín Ramírez (though we’ll never know because he stopped speaking upon his involuntary commitment to a California mental hospital in 1931).

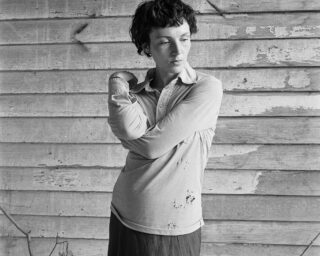

© Tomasz Machciński/Collection Bruno Decharme

The widespread availability of the camera to the middle classes by the end of the nineteenth century effected a kind of short circuit in the celestial wiring of this visionary production and even in the work of so-called outsider artists without such religious impetus. It was as if the combination of emulsion and shutter provided an accidental portal for the gods—or simply the hidden contours of the world—to slip unawares into the visible, bypassing mediation of mind and hand. Something no one saw manifests itself in the developer bath. Some kind of message is on offer. Or more commonly, a simple snapshot click yields an image of an ordinary thing unintentionally transformed into a marvel that a band of surrealists couldn’t have dreamed up on a bushel of opium.

The spirit-photography charlatan William H. Mumler—sued in 1869 for duping the bereaved with fabricated images of loved ones’ ghosts—got at the public feeling for this possibility when he hailed himself as a pioneer of “new truths” and described the camera as “a medium,” in the metaphysical sense of the word.

© the artist

Photo | Brut: Collection Bruno Decharme & Compagnie, the sprawling, messy, deeply engrossing exhibition at the American Folk Art Museum in New York, is by far the most comprehensive look yet by an American institution at how the camera’s entry into the domain of art-making materials gave outsider artists a fantastically pliable new means of expression, alluring especially because of its subversive ability “to imbue fantasy with the stamp of realism,” as the art historian Michel Thévoz writes in the show’s catalogue.

The Czech photographer Miroslav Tichý, a foundational figure in the world the exhibition explores, trained as a painter, but the pallid requirements of socialist realism drove him from an establishment career. His intentionally primitive homemade cameras, with their toothpaste-polished lenses, rendered the figural (and erotic) fabric of his eccentric mind in a way that paint likely never could have anyway, accomplishing for a twentieth-century European what André Breton, in reference to Oceanic art, described as a “triumph over the dualism of perception and representation.”

With the camera, Tichý said: “I saw everything in a new light. It was a new world.”

Like Tichý, many of the artists in the show, in pursuit of revelation or titillation or self-transformation, cannot bear to leave the photographic image alone. Modernist formalism might present itself as an influence or element, but stopping at it would be like leaving the cake half-baked; far too much life needs squeezing in for such narrowness.

Collection of Robert A. Roth. Photograph by John Faier

Long before Robert Frank or Jim Goldberg began to marry handwriting and image, Lee Godie was layering language and drawing atop her photo-booth portraits. Steve Ashby migrated photos onto wooden sculpture and lamps (he called them “fixing-ups”). Eugene Von Bruenchenhein dyed and double-exposed images. Karel Forman used them to ornament every square inch of his tiny, drab Moravian apartment. Elke Tangeten embroiders them with wandering stitches, bequeathing objects that feel both lovingly handcrafted and pockmarked with contagion.

Throughout the show runs a fever-pulse feeling of film as a miraculous gift especially to artists with emotional and developmental disabilities, offering a way that no other medium can to gobble up, make sense of, and rearrange the world, reminding me of my favorite observation about the camera’s stupendous capacity, from Lee Friedlander: “I only wanted Uncle Vernon standing by his own car (a Hudson) on a clear day, I got him and the car. I also got a bit of Aunt Mary’s laundry and Beau Jack, the dog, peeing on the fence, and a row of potted tuberous begonias on the porch and 78 trees and a million pebbles in the driveway and more. It’s a generous medium, photography.”

The artist I kept returning to in the show, time and again, is its most spartan and tranquil, an outlier in an assembly of often cacophonous outliers. Elisabeth Van Vyve, a woman with autism and hearing problems who now lives in a retirement home in Antwerp, has used disposable color-film cameras for decades to catalogue her circumscribed visual environment in obsessive detail, creating albums of thousands of snapshots that inevitably evoke the postmodern banal-sublime of William Eggleston, Stephen Shore, and early Fischli & Weiss.

© Clément Van Vyve/Collection Bruno Decharme

Except that in Van Vyve’s case, the achingly precise arrangements of color, object, and light—a pair of striped gloves lying side by side on a plaid bedspread, a white dress shirt hanging in a white corner, a yellow custard on a cane chair, clear water swirling in a bathtub, twilight cloud banks seen through a window—feel like images born not of scopophilic necessity, as Eggleston’s can, but of absolute necessity, as imperative to Van Vyve’s daily survival as eating and breathing. This is the vocation of a person documenting her world while also building its exalted counterpart in physical art objects.

In an interview for the exhibition, the French filmmaker Bruno Decharme, whose collection constitutes the majority of the works, aptly describes the sense in which these wildly varied artists share a language spoken beyond the conventional art world, bringing its own into vivid utterance: “Their works are like music scores playing on a parallel stage in another time; they could be called mythological.”

PHOTO | BRUT: Collection Bruno Decharme & Compagnie is on view at the American Folk Art Museum, New York, through June 6, 2021.