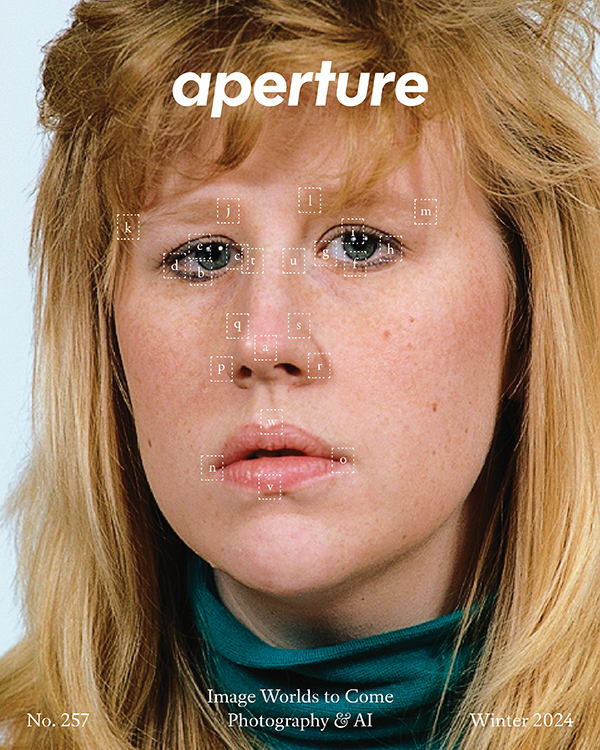

The Camera as Portal

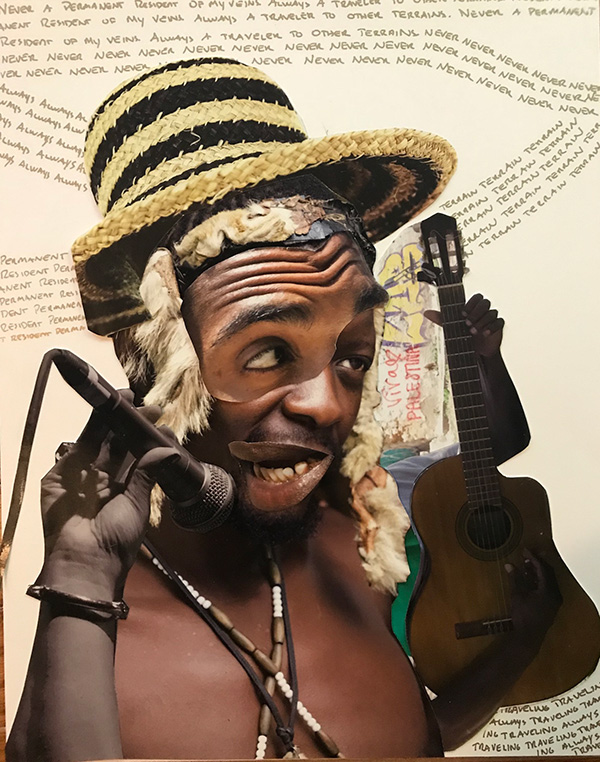

Shani Jamila, Been Running Like a River, 2018

Courtesy the artist

Sitting on one of the easternmost shores of the United States, I close my eyes and listen to the Atlantic surf. Round and tumbling, like wet fabric flapping in strong wind. I am thinking of the violence witnessed by this ocean and this shore. This meeting point of water and land brought people ready to claim territory for a faraway king, not caring that Algonquins and so many other native tribes had lived on this terrain for thousands of years. The colonists also captained boats of human cargo from Africa to create wealth for themselves and the monarchy. Waves of immigrants from the world over have made their homes here. Every day people continue to cross invisible borders to seek a better life; many are making forced migrations brought about by the realities of power, war, and wealth exerted upon them. With the water in front of me, I’m thinking about how to live on these shores in the wake of these histories that are so very present.

Artist Shani Jamila has her own answers, answers that center diaspora and mobility, physical and intellectual, in photographs and collages that capture people and landscapes in foreign lands, as well as here in the United States. Having traveled to nearly fifty countries, she tells stories and makes meaning of the structures we have created to see ourselves and our differences in this globalizing world. The photographs and collages are both documents of travel and a visual journal of her thinking through space and time. The collages mash up faces, eyes, noses, and surreal abstractions of the human body, many of them making music, connecting what is similar and familiar rather than foreign. They represent the pleasure of movement, and they are resistance.

Jamila’s solo exhibition Portals (2017–18) has a title both evocative and profound. I imagine the portal of her camera, door to other lives and new experiences, even the door of no return, the edge of precarity and loss, the unknown. These are her gifts to her viewers. In the spirit of the exhibition, Jamila, curator Larry Ossei-Mensah, writer and photographer Teju Cole, and I got together to talk about the show, photography, meaning, and travel. What follows is an edited excerpt of this conversation that addresses mobility and its implications, particularly for black bodies in our times, and the meaning of images produced by Cole and Jamila. Both, in their diaristic approach to photography, contend with how constructions of home, borders, and nationality, among other intensely felt notions, are largely figments of imagination that, while powerfully experienced, are equally slippery when parsed. Further, Jamila and Cole both confront subjective and objective visibility of themselves as photographers, seers, and artists. The result is a complex discussion that emerges from the wake, in Christina Sharpe’s terms, often asking: “How are we beholden to and beholders of each other in ways that change across time and place and space and yet remain? Beholden in the wake, as, at the very least, if we are lucky, an opportunity (back to the door) [back to the Portal] in our Black bodies to try to look, try to see.”

Shani Jamila, Ulises Double Portrait, 2017

Courtesy the artist

Laura Raicovich: Shani and Larry, you both grew up in the States, right?

Shani Jamila and Larry Ossei-Mensah: Yes.

Raicovich: And Teju, you came to the United States when you were seventeen, having grown up in Lagos. How is your experience of travel inflected by that personal history?

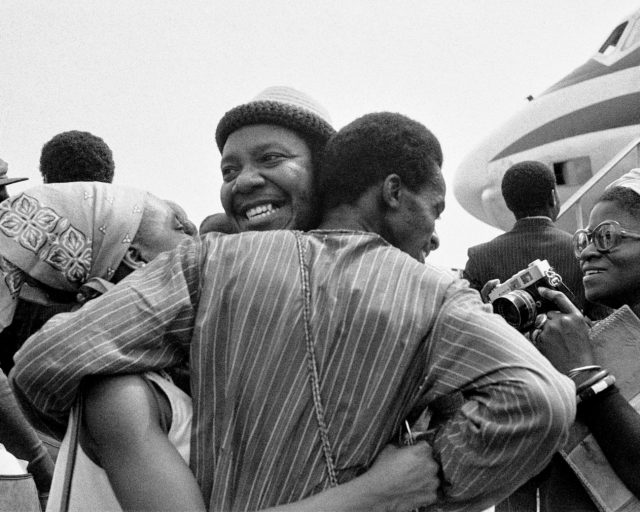

Teju Cole: Larry grew up with African parents in the US, Shani grew up with African American parents, I grew up with African parents in Africa . . . But we three very much have a share in a kind of black global cosmopolitanism that becomes the lingua franca between us. The first fact is that we’re black and traveling.

Ossei-Mensah: A lot of my travel has been guided by curiosity and a desire for understanding. I do a lot of listening. I visit with artists and try to figure out how I extrapolate what I’ve learned and put that into the work that I do, whether an exhibition or essay.

Jamila: No matter how many times I step on a plane, I never get jaded about the idea that we’re able to traverse from one part of the world to another in a matter of hours.

There’s a privilege that comes with having an American passport in terms of our ability to be mobile, or the lack of a need for visas in a number of countries, or in terms of how you’re received once you get there. Once people hear your accent, sometimes the way you’re treated will change from the way the black folks who are indigenous to that country are treated. It can be jarring. So, it’s a privilege to travel, but then I think it also causes you to check your privilege internally.

Cole: That’s right. What’s particularly interesting to me is the impossibility of being a neutral black traveler. I think what we have to offer to history, historiography, to writing, to photography is our inherent subjectivity. If a lot of heteronormative white patriarchy is predicated on an impossible neutrality, we’re present to give light to that. When you walk into any library in any of the fine schools you folks have graduated from, 95 percent of the books are by straight, we’ll assume, white men. The standard pose is, these are the facts about this particular subject, I have no influence on any of this. When I started my work, it became clear to me that objectivity was neither interesting nor possible.

Jamila: It’s a pretense.

Cole: We know that we cannot leave behind our subjectivity, nor the subjectivity of our interlocutors, because we’re always already subjective. That’s what it means to be black in this country, to be in a position that isn’t the mainstream, and then that inflects every travel experience.

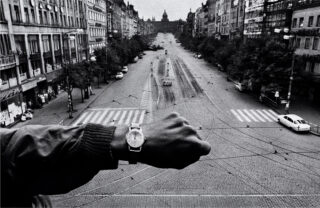

Teju Cole, Zurich, 2014

Courtesy the artist and Steven Kasher Gallery, New York

Raicovich: Is the representation of that subjectivity happening through the photograph?

Jamila: The way that’s influenced me as a photographer is that when I’m making portraits of people, I’m aware of what it means to be a subject who’s been objectified as well. So I pay attention to the cultural context in a specific country and their cultural attitudes around the idea of photography. Because even the language of photography is often very imperialist: I’m taking your picture, I’m capturing this image.

Cole: Or militaristic: I’m shooting you.

Jamila: Right.

Cole: I’ve got you in my sights.

Jamila: Yes . . . there are all these things to be aware of and to negotiate.

Shani Jamila, Matanzas, 2017

Courtesy the artist

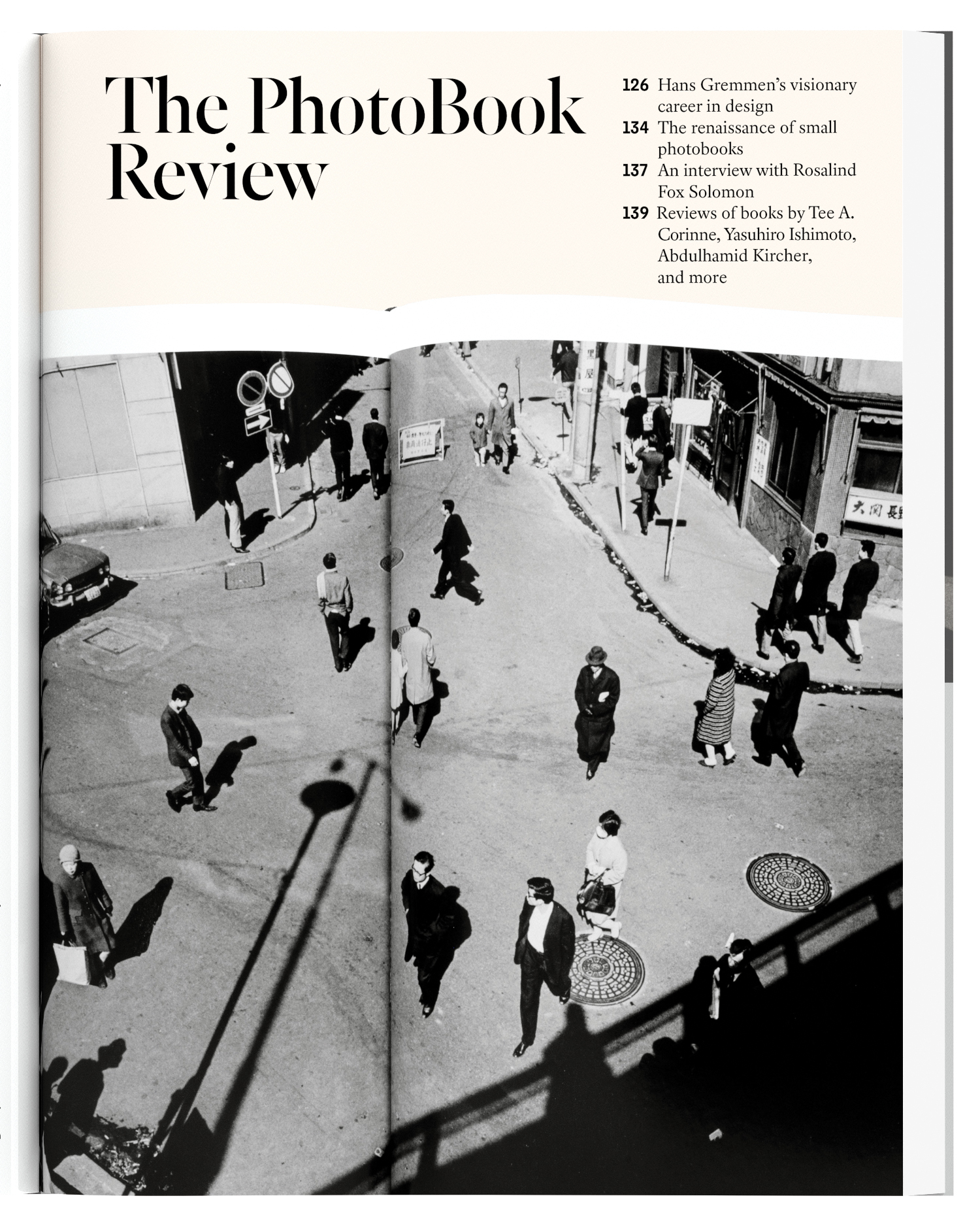

Raicovich: One of the remarkable things that bridges Shani’s and Teju’s work is a commitment to a very specific type of storytelling: a storytelling that is not facile. It is certainly legible, but not uncomplicated. It’s demanding of us, and requires a commitment to a type of image-making that is both evocative and without nostalgia for places traveled and people encountered. I want to explore why this might be so.

Cole: One of the really fascinating things about photography is its testimonial quality. Every photograph seems to declare, “I was there when it happened.” In an effort to subvert that, I’m usually there when nothing happens. Even when something is happening, I’m turning to the part where nothing is happening, because the stillness of the ongoing indecisive moment can be more revelatory.

But, you also simply cannot escape the fact that we carry cameras with us all the time, and working in this quasi-testimonial, quasi-diaristic form means that you’re actually catching a lot of life on the fly.

Shani Jamila, Long Live, 2018

Courtesy the artist

Ossei-Mensah: I think Shani’s photographs bring you closer to her. They’re a portal to how she’s seeing the world, how she’s experiencing the world, and how that’s shaped who she is as a woman right now.

Cole: I think one of the strongest things that immediately comes across is the sociality, maybe even the extroversion, of the many people you’ve encountered. But then, there is definitely a sense of you that’s somehow embedded in there. When you look at a photo, the body of the photographer is implied, even if not present, because somebody’s going around doing that and seeing things. Photos have to be—they generally have to be the result of adventure. One must be in the world making images.

Jamila: This idea of implied bodies also undergirds my collage work. They are largely sourced from portraits that I’ve made in the course of my travels and merged into surrealist images. I want to catalyze conversations about what it means to be at home and how identities are formed in a globalizing world.

Even in my film that’s playing in the back room [of the Portal exhibition], Altar—there’s a point midway through where my body leaves and then all you see is shadow and silhouette.

Raicovich: So, you’re denying it, you’re denying access.

Jamila: My body is interchangeable, almost as an avatar. The film was shot in three different locations throughout Italy. I wanted to find places that were once sacred, but they’re now desecrated or no longer considered sacred. It felt like an apt metaphor for our bodies in this country. I inserted myself into these spaces and this organic sort of processing began.

I was far away from the US at a moment where I felt like, as an artist, I needed to be able to give witness and to document and to fight for our human rights—the most fundamental of which is the human right to life.

Cole: You have images in here that are not simply taken by you, but in which you’re the subject. It’s like you’re saying that you’re not going to pretend that there was a disembodied eye that took these. In fact, here you are in the picture, a picture either taken automatically by the camera or with the help of someone else. And so, you’re asserting that what actually matters is not to press the shutter, but the agency involved in selection.

Jamila: Right. It’s all stills—everything in this exhibition is photo based, whether it’s the collages or the film or the photos themselves. They’re all part of a multilayered conversation about what it means not just to preserve ourselves, but then also to be in response, constantly, to whatever it is that’s happening in the world . . . in any given moment, in any cultural context.

Teju Cole, Black Paper, 2017. Performance at Performa 17, New York

Courtesy Shani Jamila

Raicovich: I want to connect what Shani said about the film and using your physical body in space to Teju’s recent performance at Performa 17, Black Paper.

Cole: I had to put my body out there and express the fact that this was a moment that called for an extreme experience. It was a question of, what’s actually at stake here? Bodies are at stake. And it is visceral, it is physical, it is corporeal, it is personal, it is on your skin. The anger is in my body when this guy’s trying to like gin up violence against Muslim people who are our families and our neighbors. That anger is not just for me.

A lot of it was thinking about what is happening in darkness, what is visible in darkness and what’s not. So, very much a burial in fact.

Jamila: They tried to bury us, but they didn’t know we were seeds, as the saying goes.

Cole: I find myself thinking about ancestors a lot more, just because we need help. One’s own personal ancestors, but then there’s questions of people who spoke to the moment.

A friend texted me like, “Man, fuck all this! All I can deal with right now is John Coltrane.” People are really desiring quality, like sitting with friends and listening to Nina Simone. You want somebody who’s really speaking to the deeper thing.

Jamila: Well, it’s necessary to just remember ourselves. We’re not all fight all the time. Like who are we when we’re not just engaged in this battle? And so, Nina Simone and John Coltrane will save your life.

Cole: Saved mine.

Jamila: Yeah, mine too.

Teju Cole is a novelist, essayist, photographer, and photography critic for The New York Times Magazine.

Shani Jamila is a Brooklyn-based artist, photographer, and cultural worker. A selection of her collages is currently on display at the Manifesta European Biennial of Contemporary Art in Palermo, Italy, through autumn 2018. Portals was on display at Art@UJC in Battery Park from October 2017 through March 2018.

Larry Ossei-Mensah is an independent curator and cultural critic and a cofounder of ARTNOIR.