The Mass Observation exhibition at Photographers' Gallery, London

As was proclaimed in 1937, the year of its inauguration, Mass Observation (MO) was in part established to create an “anthropology of ourselves.” Understood as a radical experiment in social science, art, and documentary form, the MO was established by ornithologist and explorer Tom Harrisson, the journalist and poet Charles Madge, and the filmmaker Humphrey Jennings, soon accompanied by the photographer Humphrey Spender and later on by the less well-known photographers John Hinde and Michael Wickham. It sought to unpack both the banalities and mythologies of pre-war British life—with a problematic, but nevertheless utopian, desire to bring together science and art in the exploration of everyday experiences. It soon constituted a vast archive of collected data which ranged from anecdotal evidence gleaned in pubs and then meticulously recorded to questionnaires about the arrangement of ornaments on mantelpieces or the popularity of various pin-ups.

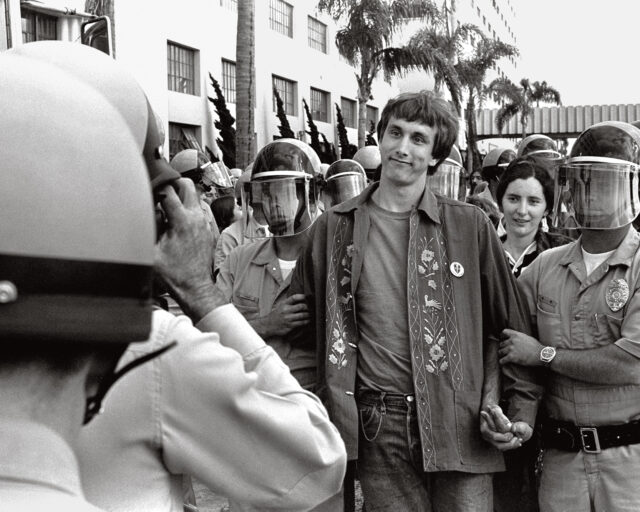

The MO’s expanding archive was conceived as a kind of vernacular museum of sounds, smells, foods, clothes, advertisements, newspapers—one largely created through texts, questionnaires, records, diaries, documents, and, of course, photographs. The current exhibition across two floors of the Photographers’ Gallery is dedicated to examining the role played by the latter in this archive. Indeed, while photographic documents were to wreak havoc with the rigorous and aestheticizing regimes of the traditional museum, the medium of photography and its messy complexities played a far more generative role in the sprawling, contradictory collections of MO. The first gallery relays this through the presentation of a jumble of photographic series, documents in vitrines, and other ephemera that focuses on life in rural England, Bolton, Blackpool, and London from 1937 to 1948. This includes a series of Spender’s black-and-white prints of working-class subjects made on the streets of Bolton in 1937–38. Spender’s characteristically surrealist eye alighted upon children’s chalk graffiti and provocative posters declaring “Truth Is Stranger than Fiction.” It’s a line that could also be taken as the photographer’s own manifesto. Indeed, exhibition curator Russell Roberts proposes this show in part as an attempt to grapple with the MO effort to produce “a new kind of realism.” The tensions between leisure and surveillance or between surrealism and sociology—certainly at the heart of artistic realism in the 1930s—have also come to be understood as dictating the central contradictions of the failed dream of MO: its instrumentalizing yet unscientific attempt at an anthropology from below.

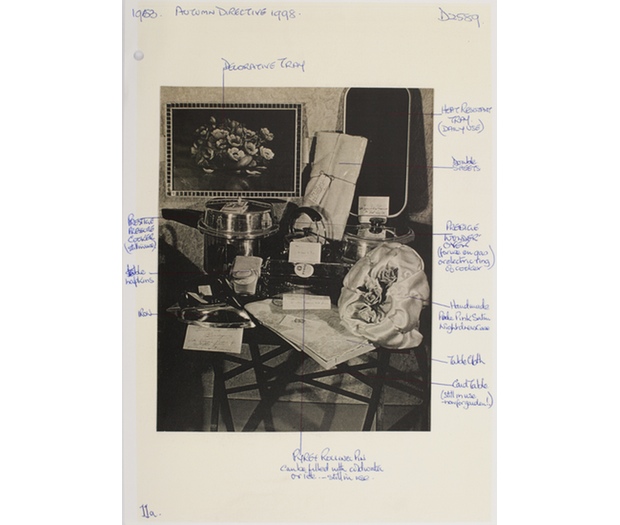

Taken from Present Giving and Receiving, 1998. © The Trustees of the Mass Observation Archive; courtesy of the Mass Observation Archive; reproduced with permission of Curtis Brown Group Ltd, London, on behalf of the Trustees of the Mass Observation Archive.

The MO project was also plagued by the obvious tensions between a group of largely middle-class observers and their working-class subjects. This is made clear at various points in the exhibition, but the potentially progressive aspects of MO are also highlighted in an engaging vitrine that brings together documentation of the establishment of art history classes by Northumberland miners and demonstrates the possibilities of working-class art education. The exhibition is most interesting when it tries to do more than neutrally illustrate such tensions. Too often it seems to skim these issues superficially, rather than historicize, critically examine, or politicize them. Despite the investment in presenting the unruly archive, there is also a latent aestheticization of some of its objects. For example, artist Julian Trevelyan’s shambolic suitcase, stuffed with various artistic materials, is presented very near the art-education vitrine (described above) as a kind of installation, nullifying any specific social tensions in favor of a rather poetic embrace of MO’s own mythologizing.

Alongside a careful investment in untangling photography’s role in the early history of MO, the major focus of this exhibition is to make concrete connections between the 1930s and the present day. In 1981, Mass Observation was re-inaugurated by the anthropologist David Pocock, and material from this new incarnation dominates the second-floor galleries. Volunteer participants’ photographic and textual responses to various “directives” from 1987 to 2012—encompassing their homes, gardens, and gift-giving habits, among other subjects—are presented on shelves behind Plexiglas screens. These include many fascinating images and offer social insights. They also suggest obvious connections between the kind of tensions that emerged between the public and private in the MO archive and those now endemic within social media and social networking. But it is not made clear enough that these later initiatives began after the original founders of the MO disbanded and the project was effectively privatized and transformed into a market research company. Such a critical examination of the MO might have required more ambition and a full three floors.

Taken from The Garden and Gardening, 1993. © The Trustees of the Mass Observation Archive; courtesy of the Mass Observation Archive; reproduced with permission of Curtis Brown Group Ltd, London, on behalf of the Trustees of the Mass Observation Archive.

As it is, so much more could have been done with the earlier material. For example, it would have been fascinating to know more about the fallout between Madge and Harrisson because of the latter’s decision to collaborate with the Home Intelligence Department of the Ministry of Information; or photography’s displacement in favor of graphic design in the frenzied desire to relay complex information in abstract form. (This is briefly alluded to in the show via diagrams by the bizarre Isotype Institution founded by Austrian émigrés Otto and Marie Neurath.) Further, so much is left unsaid about the unfolding exchange between photojournalism and the MO, or the relationship between psychoanalysis (also key to the MO) and photography. Both issues were central to the radical and reactionary new realism of the MO, as they must be to any attempt to properly reengage with its legacy.

Sarah James’ book Common Ground: German Photographic Cultures Across the Iron Curtain was recently published by Yale University Press.

Mass Observation remains on view at the Photographers’ Gallery, London, until September 29.