Publisher Profile

TBW Books

Matthew Leifheit in conversation with Paul Schiek

So often in art—as in life—the decision to prioritize someone else’s dreams, even temporarily, is looked at as if it means one’s own artistic vision and conviction may be wavering. Paul Schiek, a photographer and independent publisher based in Oakland, California, has been curating, writing, and publishing under his imprint TBW Books, in addition to making his own photographs, for the past ten years. He seems to see this varied outpouring as a medium in its own right. His generous vision is perhaps most evident in TBW’s Subscription Series, an annual set of four distinct books that share a common format and design. The series acts like a less ephemeral form of periodical: evolving, sequential, and malleable. Specifically, TBW’s Subscription Series brings to mind Wallace Berman’s Semina—not only because that was also a Bay Area publication that brought together disparate artists under a sort of hand-hewn umbrella, but because Berman himself was an artist bashful about showing his own work. Over the course of an hour in early September, Paul Schiek and I talked about the evolution of TBW Books in relation to his life since 2006.

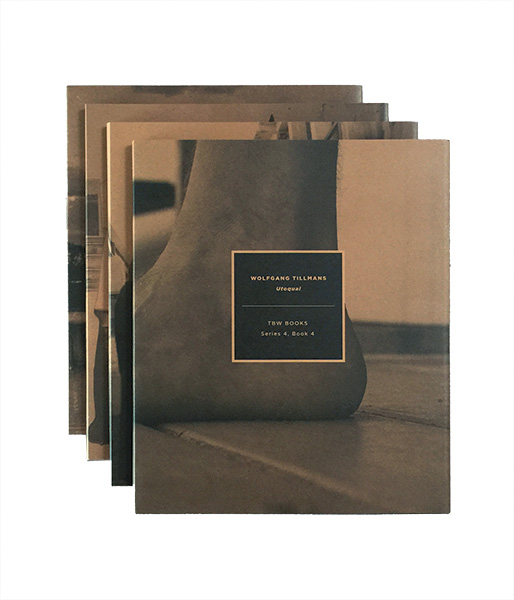

Subscription Series No. 4

Includes Christian Patterson, Bottom of the Lake; Alessandra Sanguinetti, Sorry, Welcome; Raymond Meeks, Erasure; and Wolfgang Tillmans, Utoquai • TBW Books • Oakland, CA, 2013

Christian Patterson

Matthew Leifheit: So, the big question: why publish books?

Paul Schiek: I did my undergrad at California College of Arts and Crafts [now California College of the Arts]. I studied under Jim Goldberg and Larry Sultan, and another guy named Abner Nolan. All three of those people had a profound impact on my thinking about photographs and why I make photographs today. We looked at books a lot, and we talked about books, and thought about books. There were classes dedicated specifically to photobook-making, which were really shape-shifting for me.

ML: Had you published zines previously?

PS: I came up in—I hate to use the term—the “punk” world. I grew up being around zines, collecting zines, making little zines. As I was around music, I was taking photos with point-and-shoot cameras. I had no idea what I was doing, but I was taking pictures of what was happening around me and then making things with them. Then, in my senior year at CCA, rather than hanging a show—which was our requirement for graduation—I asked Jim and Larry if they would agree to me publishing a book instead. I thought that was a much more responsible way of distributing my work, because no one knew who I was. No one had any interest in looking at my photos in a gallery setting. The book was called Good By Angels. I had to edit it down to a really concentrated set of images because I couldn’t afford to print five hundred pages. I didn’t have the money for a cover, so I decided to hand-stamp each cover with a rubber stamp. I had watched friends who were in bands do that with their records. It just made a lot of sense to me. Since photography was becoming my medium, I started applying those practices to making books.

ML: When was the first time you thought of publishing someone else’s work?

PS: After school spit me out into the world, I tried to figure out what I was doing. I was making photos, and I wanted to show them, but didn’t know who the audience would be. So that’s when I came up with the idea of the Subscription Series, which was simply to align my work with the work of three other artists. If people were interested in any of the work, then they’d see it all by default. Because they’d subscribed to this thing that’s four books, even if they only wanted one or two of the books, they’d also be forced to look at the book of my own work as well. So that’s how the Subscription Series started. It was a tool, a mechanism, to create a space for people to be exposed to my work.

ML: That method also benefits the other less famous artists you publish.

PS: Yes. By Subscription Series No. 2, I felt that my work couldn’t be in it again. So I started getting other photographers to participate. We just finished Subscription Series No. 5, which we’re very proud of. Every body of work included is over thirty years old but has never been shown before. We’re also starting to focus a bit more on special editions and singular, one-off monographs. I no longer have much interest in showing my own work; I’m way more excited and fulfilled by working on editing other people’s work, and bringing their ideas to fruition. It’s this evolving sort of thing.

Raymond Meeks

ML: I don’t think that’s a lesser art than going out and taking pictures, actually.

PS: I was taught by Jim and Larry that the actual making of photographs is only 50 percent of it, and the other 50 percent are these small, very deliberate decisions that you make about presentation, editing, sequences, paper choices, installation—all these crucial things that, in certain cases, the photographer might not be good at. They shouldn’t necessarily be expected to be good at all those things. That’s why it’s important for publishers, editors, and designers to be able to step in and round out the project.

ML: How has the Subscription Series evolved?

PS: In the beginning, it was me approaching people I was interested in working with, or friends would introduce me. To this day, reputation and personal relationships with people are a huge factor. It’s also the way I like doing business. I’ve certainly reached out to people I want to work with, and as you know, there are a million e-mails involved. These things take a lot of time on the part of the publisher, and there are people who I started working with four years ago who I might just be publishing now. Sometimes it takes that long for it to gel and get to a place where everybody is comfortable. That’s how this stuff works. In the meantime, my job is to make a better product—become a better editor, publisher, and designer—so that people will continue to trust me.

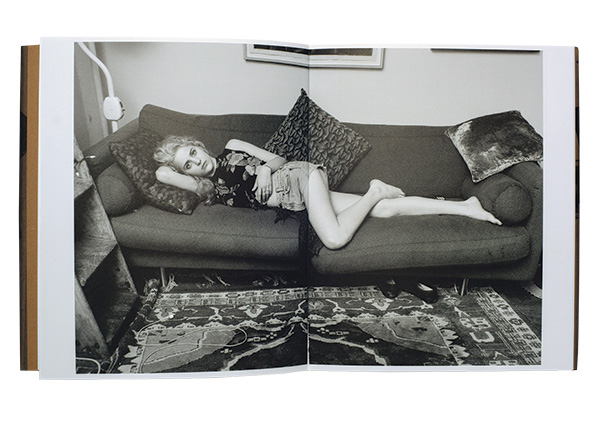

Alessandra Sanguinetti

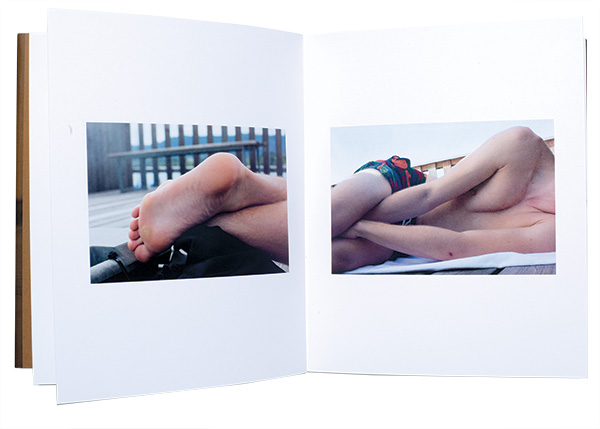

Wolfgang Tillmans

ML: You’re not just asking people to send you some files—you want to work with artists very closely.

PS: I’m very, very close to the process, out of respect for the book and the artist’s time, but also out of respect for myself and my time. Going back, it was always a dream of mine that doing a studio visit with someone and editing a book with them could be a job. Now I do a lot of different things in the photo world under the umbrella of TBW, and I have a full-time employee, Lester Rosso. I’m really proud that there are two of us working full-time on publishing now.

And so, if I’m just treating it as a business, yes, it’s much easier for me to ask people to send us the files and we put out the book and it’s done. But for me to be fulfilled and stimulated and feel like I’m doing the best job I can do with these books, I need to work as closely with the artists as possible. I enjoy packing orders, I enjoy sending e-mails, I enjoy choosing paper and being on press. I enjoy running to the post office to get more stamps. All the minutia that it takes to run a business—as long as it’s a business that’s surrounded by photography—I’m happy to do. But the most important part of that is getting to work with the artists. When you’re working with an artist, you can have dinner together, they might stay at your house, and then you fly together to do a signing. All those things that some people might call work are, to me, very luxurious. Because there are a million other shitty jobs out there that you can do, and if you’re not doing those and instead you’re talking about photography with another artist and sharing ideas—talking about what photos actually mean to them—that’s a luxury. And that’s why I need to stay super-close to this.

Matthew Leifheit is a photographer, curator, publisher, and interviewer currently studying photography at the Yale School of Art. He has published MATTE magazine, an independent journal of contemporary photography, since 2010. He is also photo-editor-at-large for VICE magazine. matthewleifheit.com