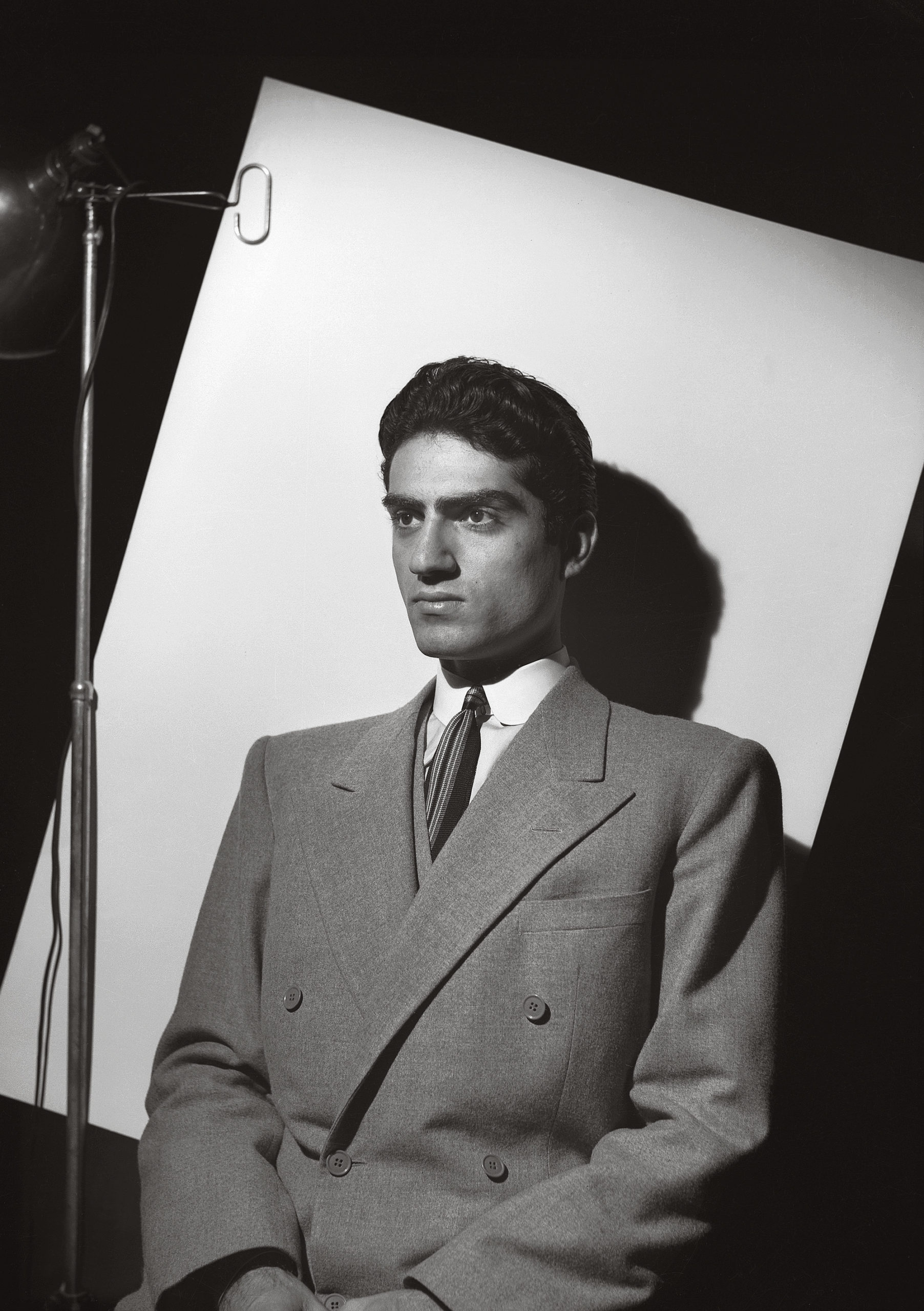

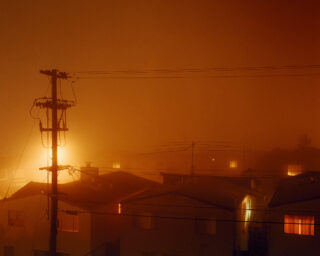

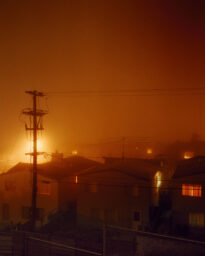

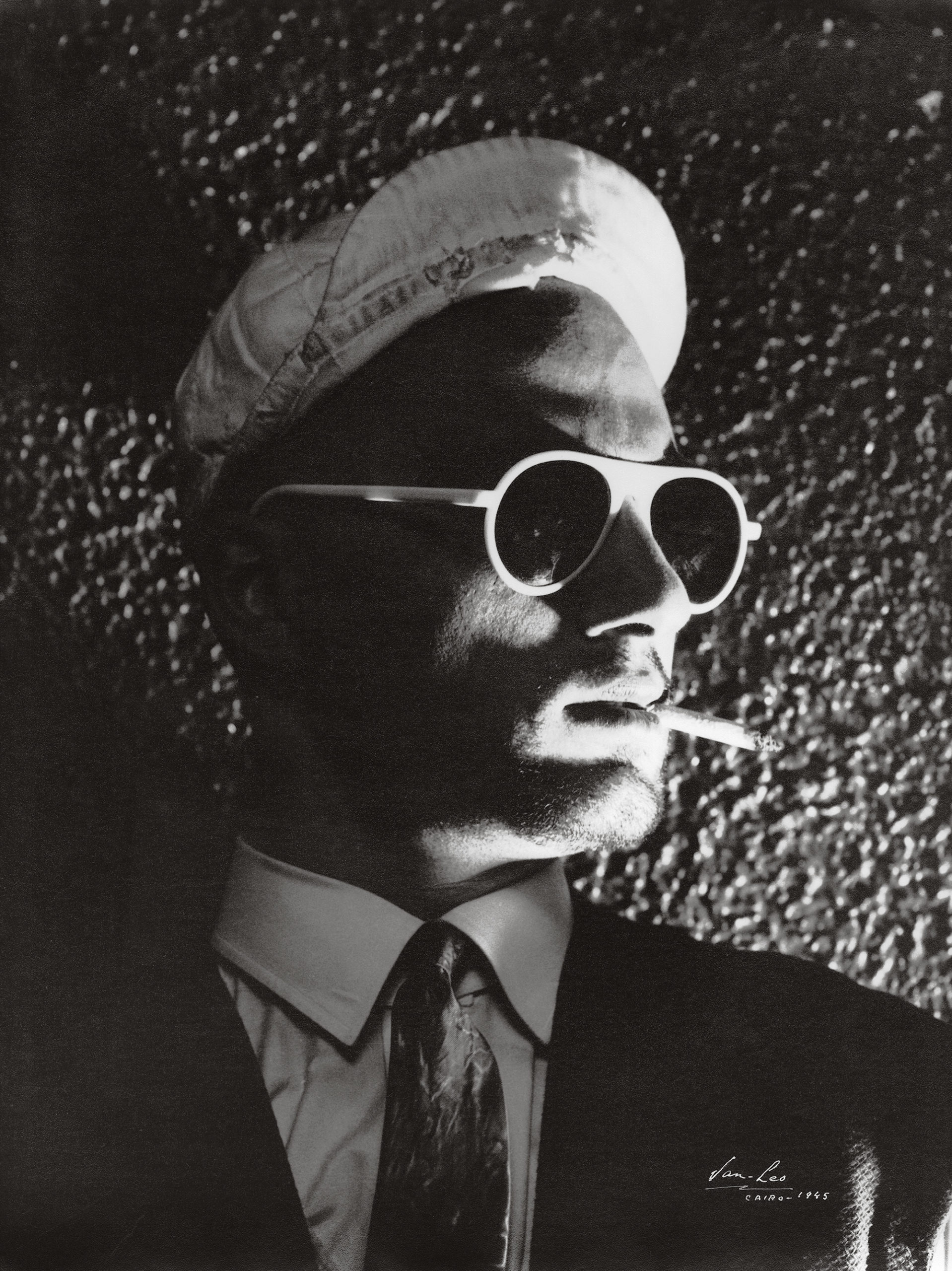

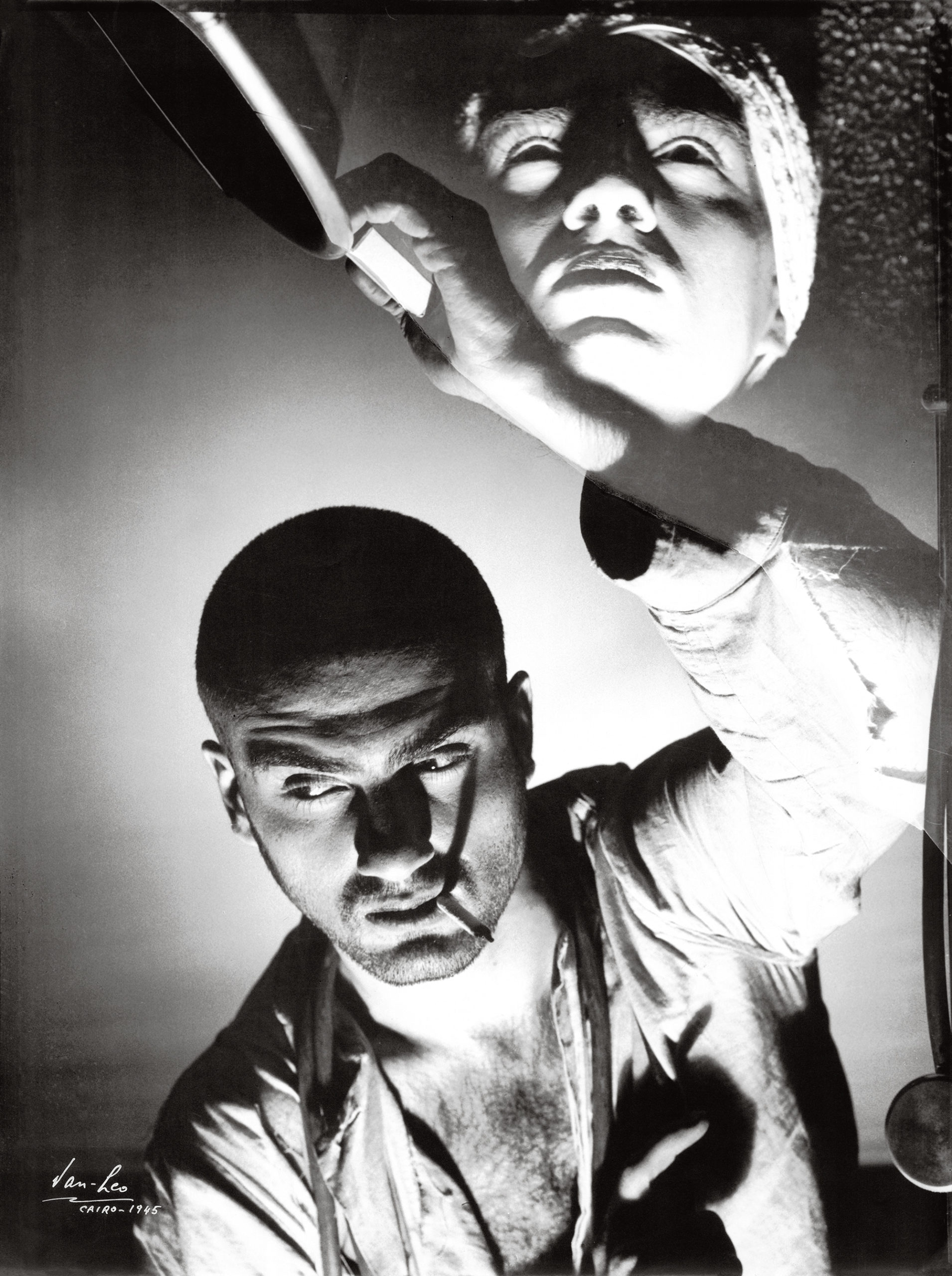

Van Leo, Self-Portrait, Cairo, February 21, 1947

This piece originally appeared in Aperture, issue 228, “Elements of Style,” fall 2017.

I have great faith in surfaces. A good one is full of clues. —Richard Avedon

Who was Van Leo? The question haunts anyone who sets out to write about him. He left behind so much for us to admire. And yet he gave us so very little. Of himself, I mean. So many unanswered questions loom. The temptation to fill the gaping holes is huge. Was he a pioneering modernist, one of the most questing and idiosyncratic photographers the Middle East has known? A man-boy narcissist whose greatest quirk was to close his studio for a few hours each day to snap photographs of himself? A savvy technician with an outsize passion for Hollywood-tinged glamour? An oriental orientalist?

When he passed away, in 2002, at the age of eighty, the Armenian with the fantastical stage name bequeathed a vast treasure trove to the American University in Cairo—several thousand prints and negatives, eclectic props and furniture, Post-it notes and shopping receipts, and drafts and obsessive redrafts of letters, both sent and unsent. Van Leo had attended the university for only a year or so in the 1930s before dropping out (he’d always been a below average student), and yet he was convinced that they would soon create a museum in his honor. An overenthusiastic autoarchivist, he told himself that nothing he’d ever touched was insignificant enough to throw out. Still, these life scraps hardly shine a light onto the photographer’s soul.

By the time I met Van Leo, in 2001, his studio had been shuttered. His body was broken, and he was living in his childhood home in Cairo, a narrow apartment at 7, 26th July Street. Inside that dark rectangle—dark because he was thrifty and strained to keep his electrical bills down until the end—he no longer walked, but shuffled. He was alone, and there was little, beyond my twenty-year-old presence, to indicate what decade it was. A wall calendar hung crisply in the kitchen from a particular year in the 1940s—I can’t remember which. Van Leo himself was cordial, occasionally charming—in at least four languages—but he was wary. Cairo had changed, he said, and he didn’t know whom to trust anymore.

*

Levon Boyadjian was born in Jihane, Turkey, on November 20, 1921, the youngest of three children of Alexandre and Pirouz, Armenian émigrés whose family name roughly translates to “one who paints.” Like so many Armenians unmoored after the genocide, they moved to Egypt—to Alexandria first, and then on to Zagazig, a medium size town on the Nile. It’s tempting, when looking at images of baby Levon from this period, all dolled up, to see the rumblings of future vanities.

The Boyadjians eventually settled in Cairo, landing on what was then Avenue Fouad, an elegant thoroughfare in the Haussmannian style that extended from the manicured topiary of the Ezbekieh Gardens to the Egyptian High Court of Justice. As a teenager, young Levon interned at Studio Venus, one of dozens of photography studios run by Armenians in that city. (The Armenians had a well-known proclivity toward the craft.) Some say that Levon was pushed out of Venus when the owner—his name was Artinian—began to feel threatened by his young disciple’s precociousness. Whether this piece of lore has a kernel of truth to it is unclear. It doesn’t really matter; it’s the first of so many myths to come.

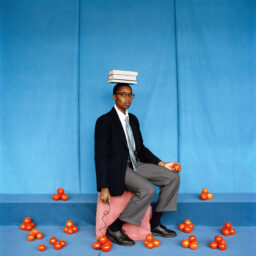

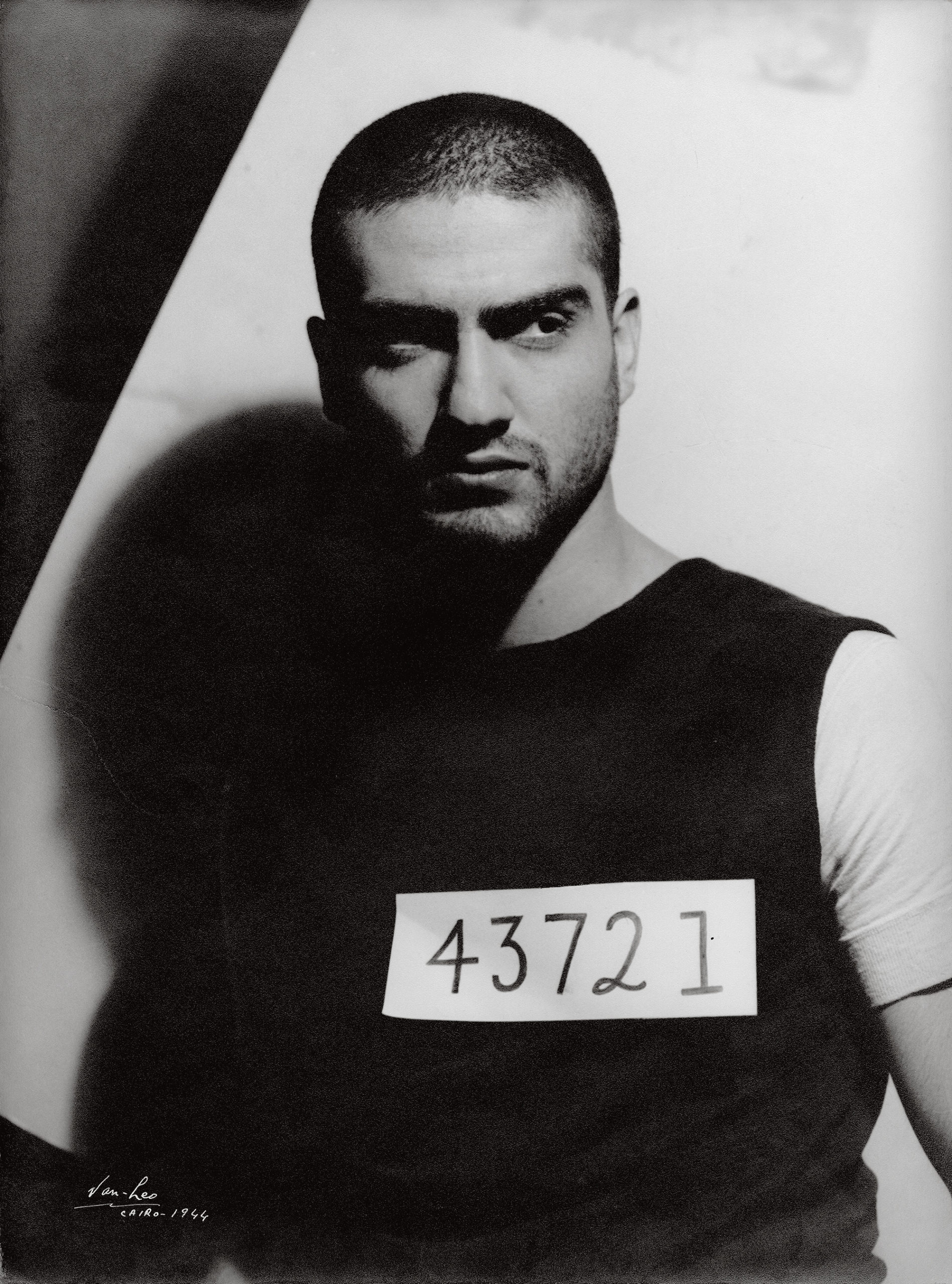

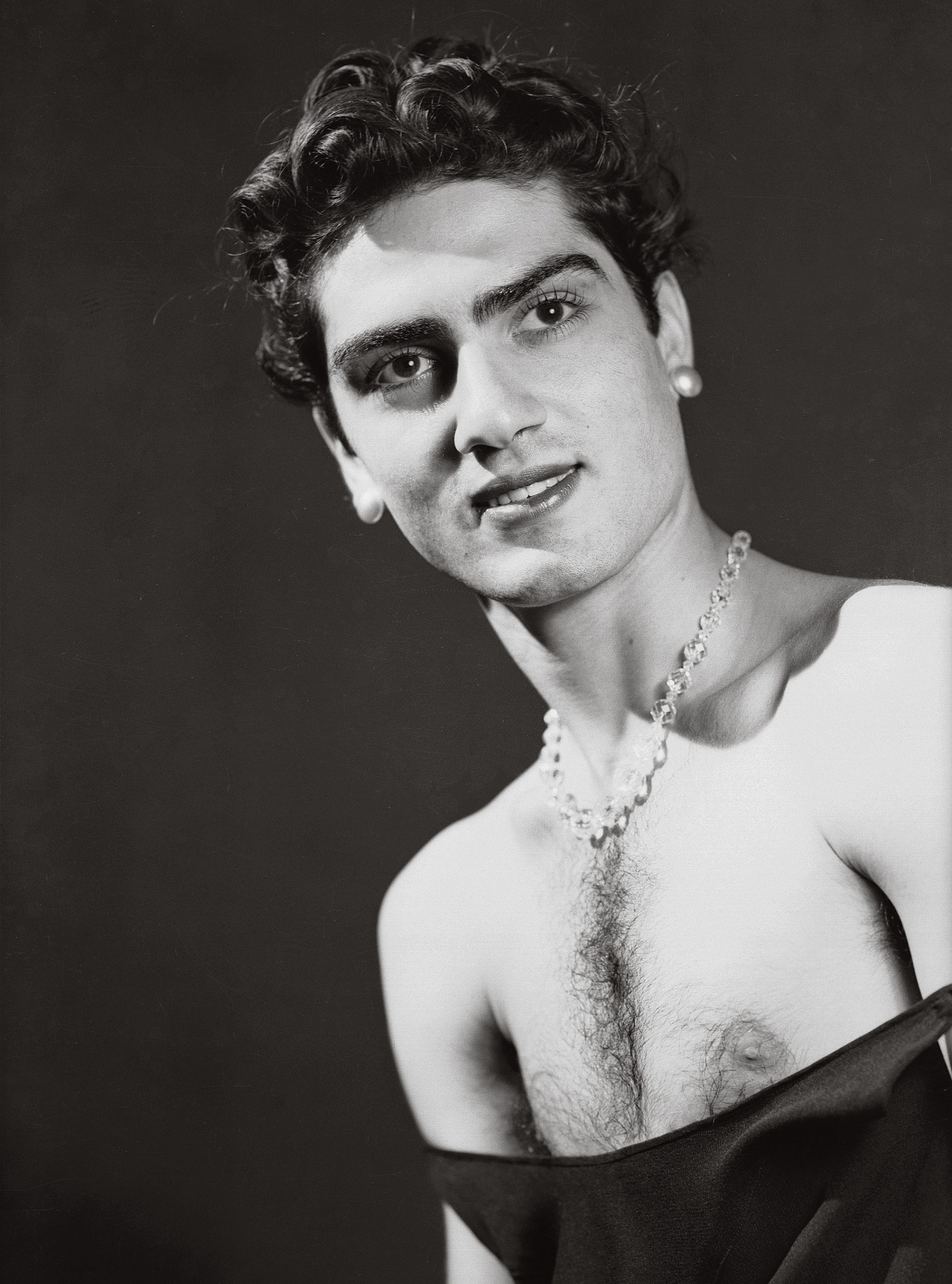

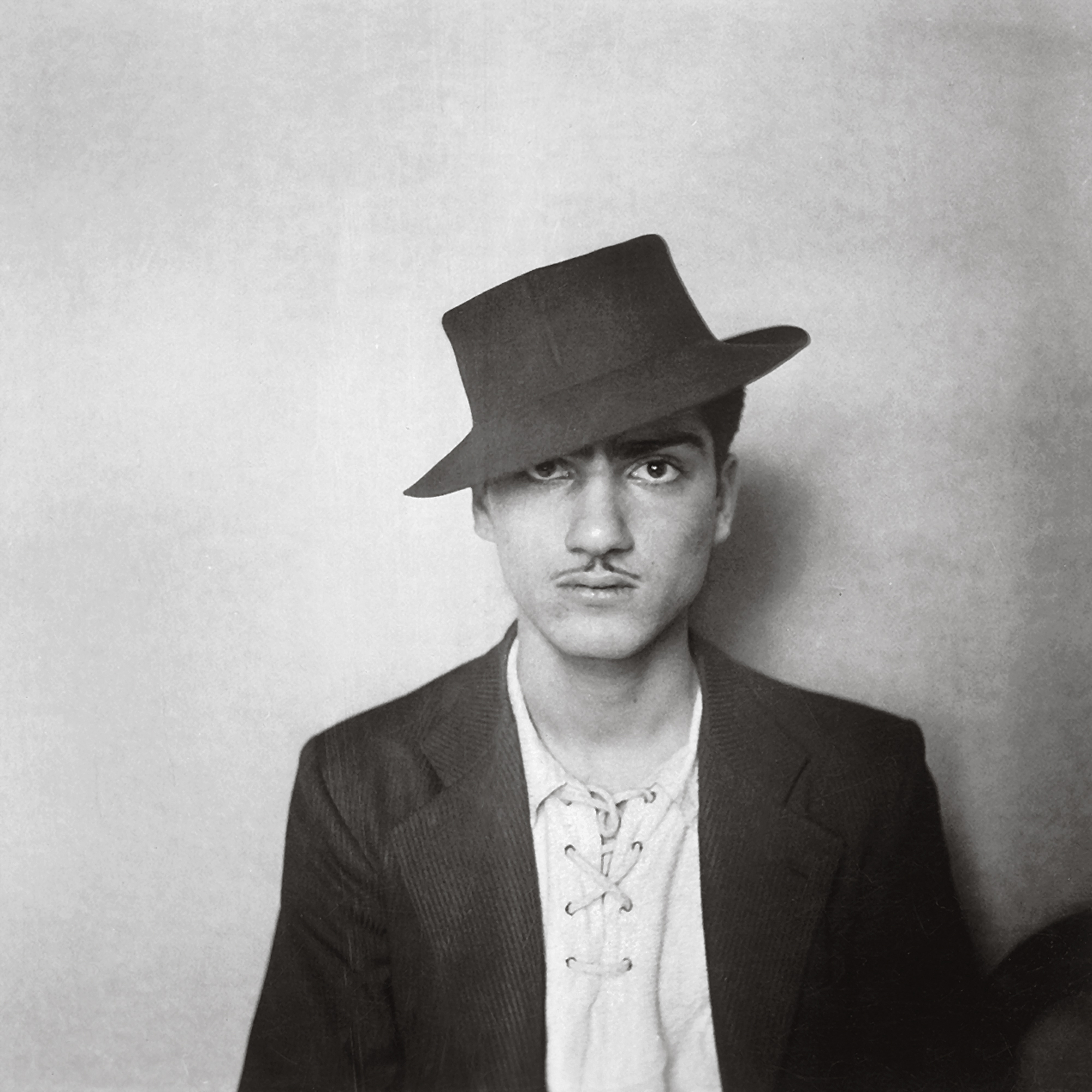

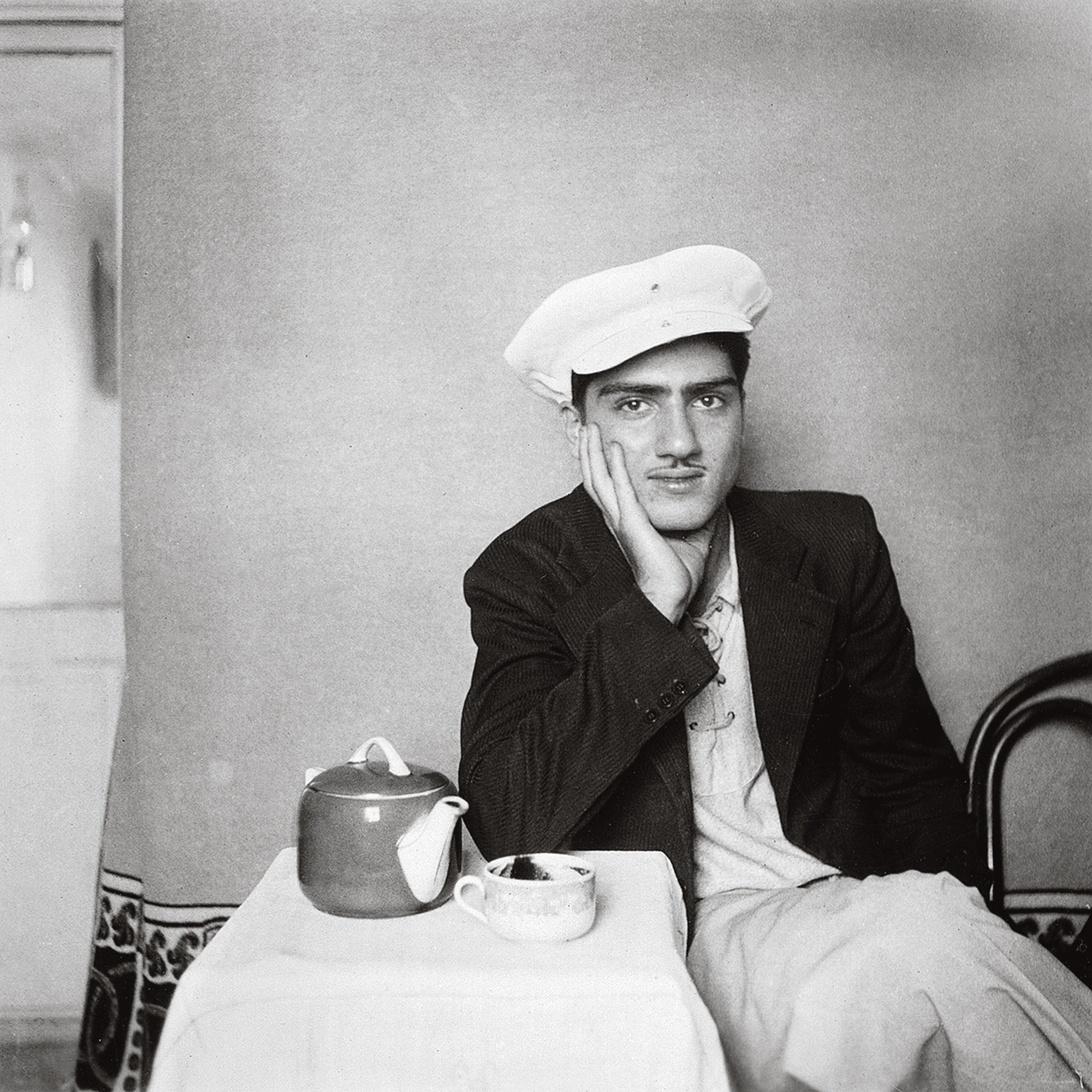

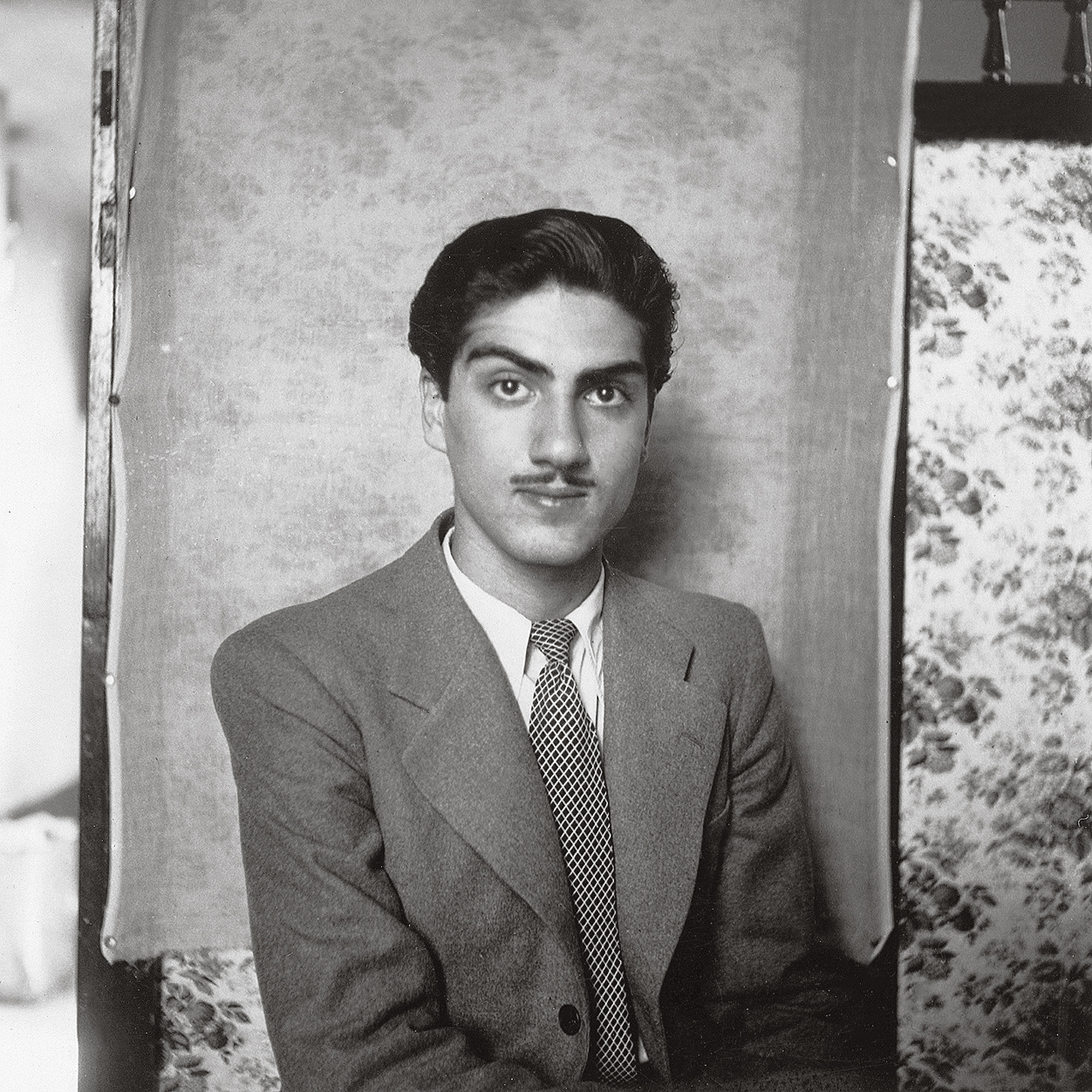

Van Leo would never have called himself the Cindy Sherman of Egypt, but between 1939 and 1944, he took hundreds of untitled self-portraits, assuming myriad personae.

It should be said that there were two photographers in the Boyadjian household, and when Levon and his brother set up shop in the family apartment in 1941, they called it Studio Angelo, in deference to the chatty older brother. The living room served as the lobby; the bathroom, the darkroom. The pair’s first customers were entertainers passing through Cairo during World War II who traded glamour shots for free advertising space in local playbills. Downtown Cairo was brimming with dancers, stage actors and actresses, clowns, and strippers—there to boost the morale of the marooned troops who were stationed in the city, soldiers from across the British Empire, as well as Americans. And yet, from the beginning, Angelo—gregarious, gambling, womanizing—was Dionysus to Levon’s bashful Apollo. While the creative partnership might have appeared happy from a distance, the two couldn’t have been more opposed.

*

In 1947, the brotherly collaboration fell apart, and Levon set out on his own, taking over a large space a few blocks from the family home, from a photographer who had left Egypt for Armenia. Studio Metro had six big rooms—“six big rooms!” he would intone, over and over, to me and anyone in earshot, decades later. It was there, at 18 Avenue Fouad, that Levon Boyadjian became Van Leo, star maker and star. The name “Van Leo,” a fabrication of his own, conjured certain Dutch masters, lapsed European royalty, and good breeding in general; it had the cadence of greatness. In the archive, there are at least half a dozen typeface experiments for the new, exotic nom de plume—thick and regal, skinny and modern, cursive and confident. Sometimes there’s a dash between the “Van” and the “Leo.” A persona is finding its way.

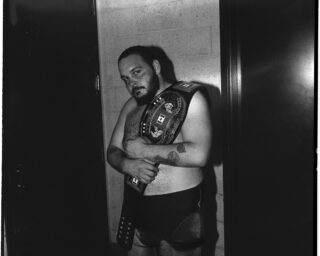

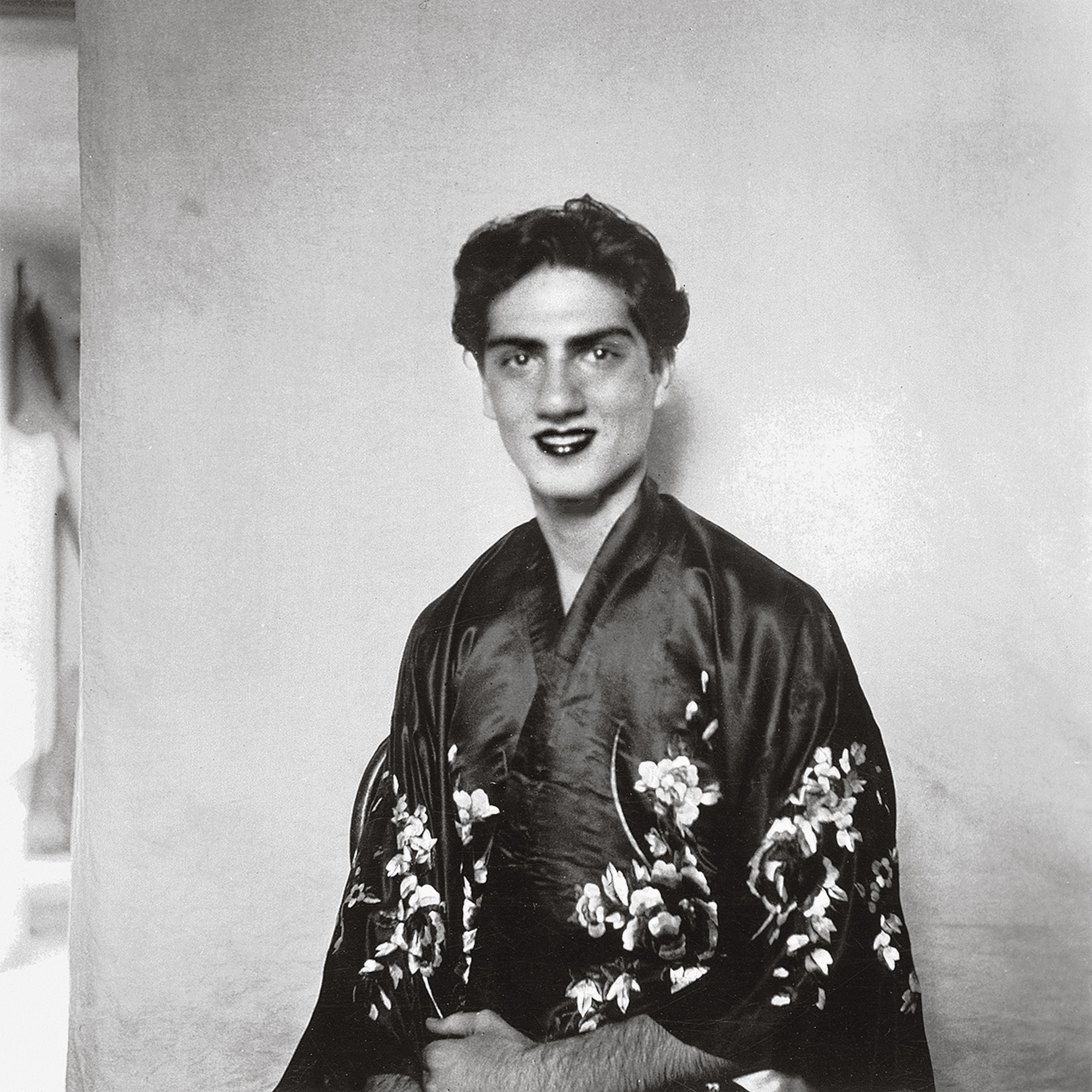

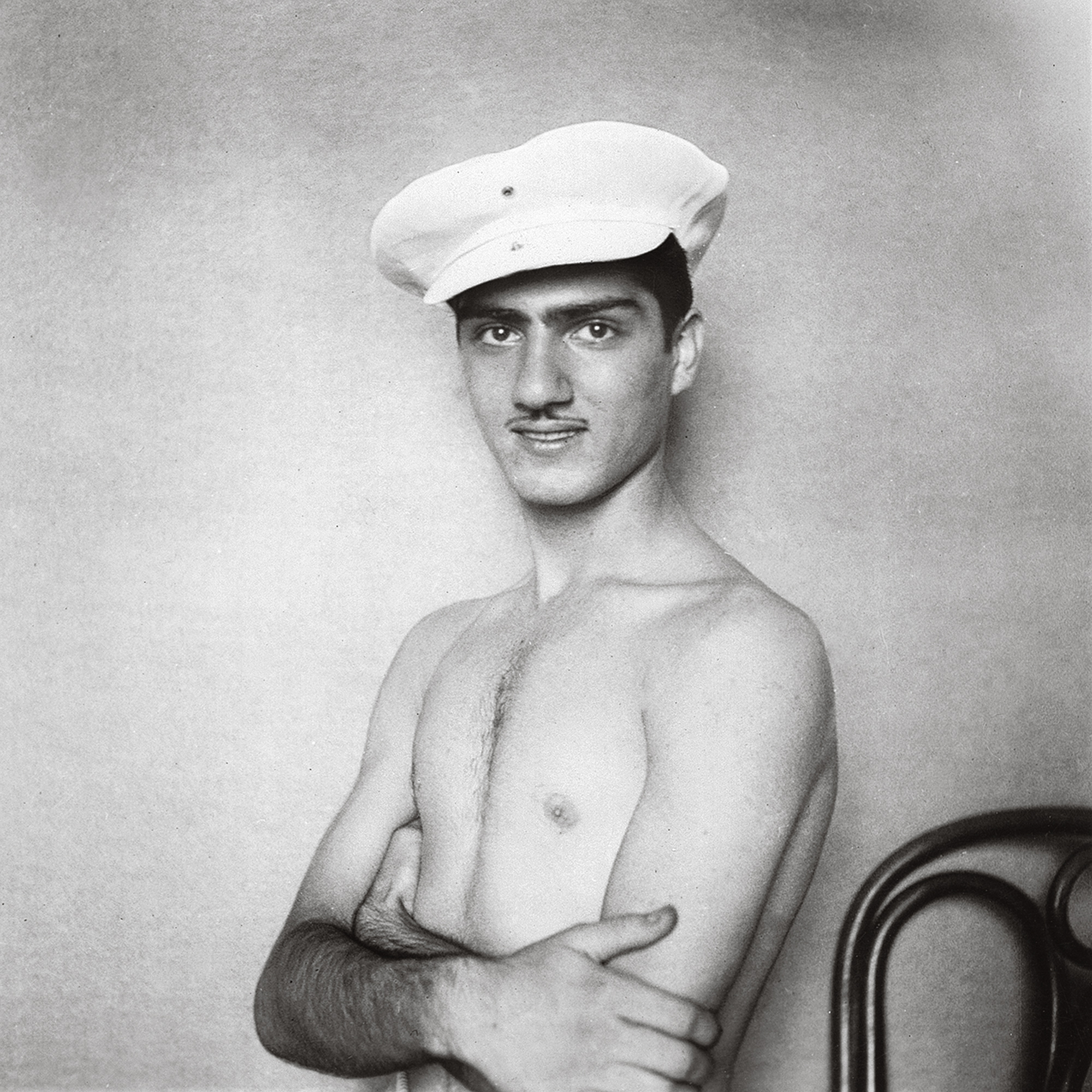

Van Leo would never have called himself the Cindy Sherman of Egypt, but between 1939 and 1944, he took hundreds of untitled self-portraits, assuming myriad personae. In these, his own body was putty—he would grow his beard, shave his head, even put on weight, while experimenting with costumes, props, and lighting. He appeared as a gangster or prisoner; as Jesus Christ, the Wolf Man, or Zorro. In one, he has the mien of a young Vladimir Lenin; another evokes the 1940s film The Thief of Baghdad. Several are surrealist tinged, betraying Van Leo’s encounter with a short-lived Egyptian Surrealist circle of the 1930s and ’40s known as Art and Liberty. “My father used to get very angry,” he admitted in 1998. “He’d tell me: ‘Did you make the studio for yourself or for the customer? Stop making photos of yourself!’” And yet it’s precisely these works in which Van Leo turned the camera on himself that began to bring him a measure of international fame in the late 1990s, shortly before we met.

In the photographer’s archive, there’s a little flip-book with dozens of postcard-size images pasted in. And yet the bulk of the self-portraits had never been printed at all. What purpose did they serve? Did they appeal to his vanity? Were they by-products of his ongoing efforts to hone his craft? Samples to show customers? Flights of fancy? It’s impossible to say. The elaborate masks Van Leo wore, one after another, were less transformative than obfuscatory. They open a door to delirious wonders, but don’t give us the key.

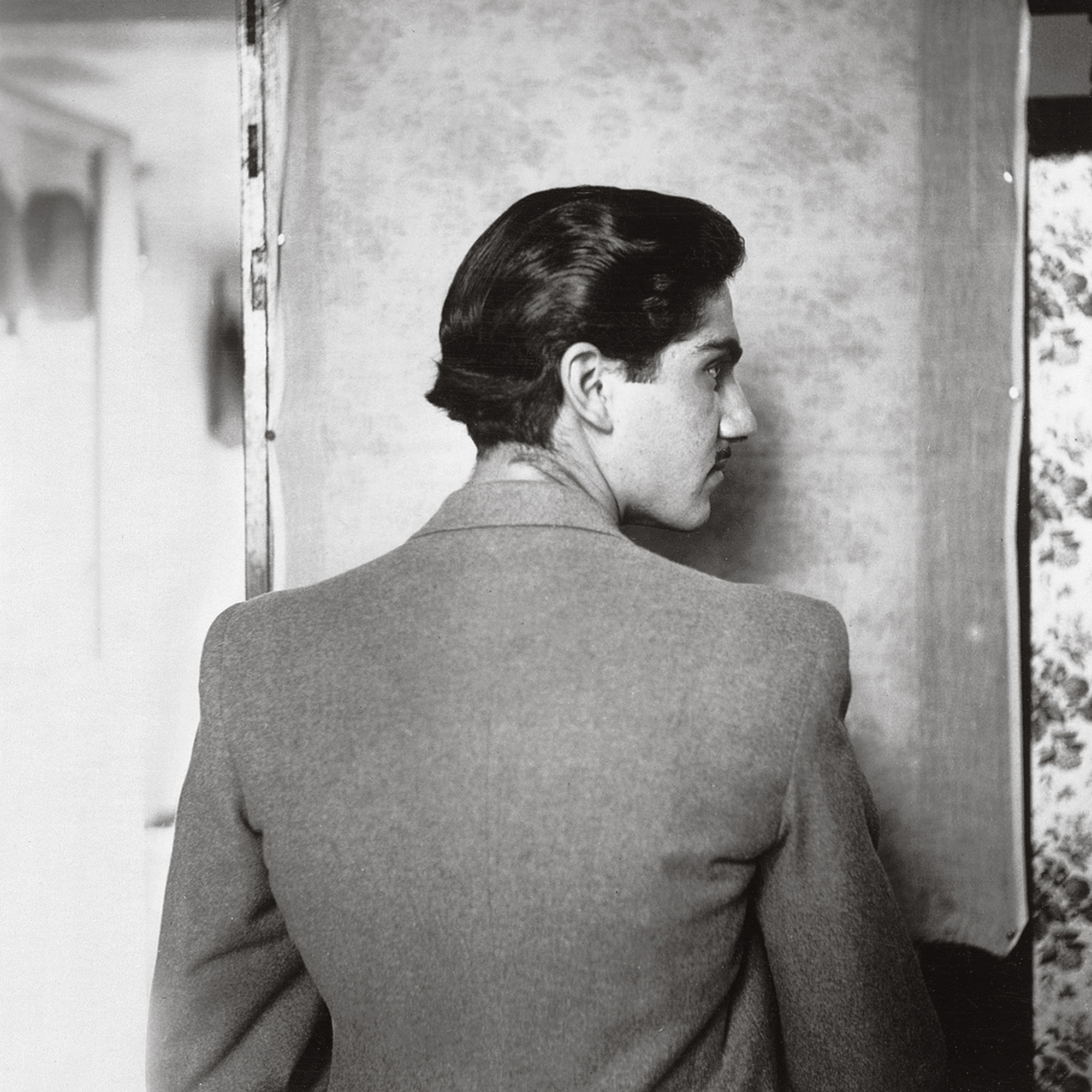

There are a couple of photographs I love the best, in which a very young Levon, barely a teen, stands against wallpaper with an elaborate floral design. There is no date, but I like to think of them as his very first self-portraits. In some, he’s wearing what must be his school uniform, starched collar erect, gazing sternly at the camera. In one, he literally stands out from the surface of that same wallpaper, his face and neck emerging from the flowers. It’s an elusive image—the young photographer’s coat is nearly identical to the pattern on the wall. Where on earth did he find that? Did he have it made? He appears to be looking at something with an air of misty reverie. On the print, his shirt and lips have been shaded pink with pencil or watercolors. By his own hand? Were these the private obsessions of a young man? A portrait of the artist as a flower.

The same floral pattern appears again in a series of photographs of a notably older Levon, dated 1939 and 1940. In this series, he strikes diverse poses and uses motley props, especially hats (pith helmet, cap, bowler). In one image, he dons blackface and has wrapped a cloth around his head, like a turban. In two others, he’s slipped into what appears to be a silky woman’s bathrobe, or a kimono. Lipstick has been smeared on his lips, and conspicuous rouge limns his cheeks. Only the slightest glimpse of a hairy arm reveals his sex. The words “In the Chinese House” are faintly scrawled in pencil on the back of one photograph. It is an altogether enigmatic piece of chinoiserie.

*

“Photography is an art, and if you are born an artist, which is a gift from God, it must be appreciated by the people. One photograph is worth ten thousand words.” Van Leo wrote these words in 1966, in response to a question about “gainful employment,” on an immigration form. He never gained much money as a photographer, and spoke extensively, even relentlessly, about the suffering his devotion to his art—to Art—had brought him over the years.

Van Leo was proud of his craft and dismissive of his rivals. But his conviction in the power of photography had little to do with the gritty photorealism of Robert Frank, or even Walker Evans’s poetic depictions of impoverished lives. He had no interest in bearing witness to ugly or inconvenient truths: amid his thousands of photographs, there are no more than a handful of unstylized documentary images. Nor was he turned off by what the writer Janet Malcolm once referred to, in an article about Richard Avedon, as the “bazaar of false values” in fashion and other forms of high-gloss photography.

On the contrary, Van Leo reveled in surfaces, sheen, and gloss. And, unlike Avedon, who underwent a transformation in the mid-1950s, opting to show his subjects as they were—saggy, lumpy, wrinkled—he played plastic surgeon to the end. His art never aspired to truth. Truth was unseemly. Art was fantasy and illusion. Beauty, for him, seemed to have a moral quality about it. Photographs, motion pictures, magazines—these were the stuff of dreams. In a notebook, he carefully and obsessively listed famous actresses alongside their date and place of birth. “Mae West: born 1893, Queens, USA.” “Jean Harlow: March, 1911, Kansas City, USA.” Hollywood was where dreams came true. The photography studio was itself a kind of dream machine.

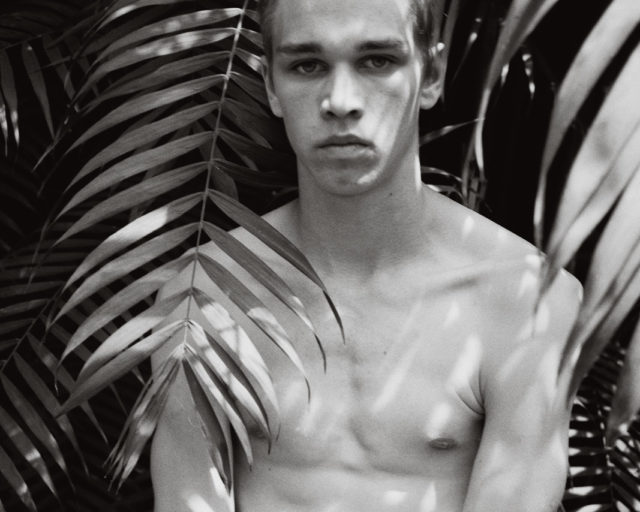

The Egyptian film industry became Van Leo’s Hollywood, offering up a steady stream of volunteers upon whom he could practice his alchemy. The 1940s, ’50s, and ’60s were the golden age of Egyptian cinema; movie houses like the Rivoli and Miami screened homegrown productions, as well as the latest American films. Like the wartime entertainers who walked into Studio Angelo, Van Leo subsidized would-be stars and starlets, convinced that their future fame would pay its own dividends down the road. One such figure was Rushdy Abaza, a half Italian insurance agent who worked in the same building. Abaza, tall and smolderingly handsome, yearned to be an actor. Years later, when he became famous, Abaza sent many others to be photographed by his old friend.

By the mid-1950s, Van Leo’s studio was probably the most celebrated in Cairo. Dozens of his portraits from that time are indelibly linked to the public images of the individuals they feature. There is the Druze singer-actor Farid al-Atrash, playing the oud in his overdecorated apartment on the Nile. There is buxom Berlanti Abd al-Hamid, who Van Leo took out to the pyramids on horseback; Faten Hamama, seductively leaning back on Van Leo’s studio floor; and Abaza himself, cigarette in mouth and pistol in hand, his body playing a shadow game against the photographer’s studio wall.

In constructing these images, Van Leo was working in a vein of high-contrast celebrity photography perhaps best exemplified by Studio Harcourt in Paris and its magazine Stars. (Some say that he, in fact, worked for Harcourt at some point, but if he did, he left no trace.) But the inspiration that mattered most to him may have been Yousuf Karsh, another Armenian exile, world famous for his portraits of celebrities and politicians, and for his masterful use of light. Dozens of carefully clipped-out articles about Karsh reside in Van Leo’s archive.

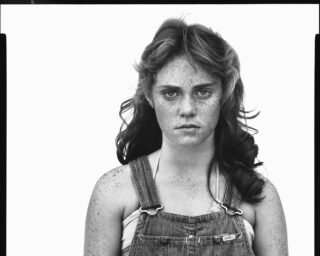

And yet the majority of the people who appeared before his camera never quite made it. Van Leo’s most unforgettable images are not necessarily of the déjà arrivés, but of the almost famous. In Camera Lucida, his 1980 meditation on photography as a new form of consciousness, Roland Barthes wrote that each time a subject stands before a camera, four people are implicated: the person the individual thinks he is, the person he wants others to think he is, the person the photographer imagines him to be, and the person the photographer will make use of to realize his art.

In thinking about Van Leo, one might add a fifth: the photographer himself. In these photographs, it’s as if Van Leo’s own aspirations for recognition and fame found echoes and companionship in those of others. The would-be leading men and women who lined up to have their portraits taken held a mirror up to his own desires, and he lost himself in their faces along the way. (On the back of a photograph of a young actress named Elham Zaki, he wrote, heartbreakingly: “She wanted to be a star.”)

Ragaa Serag, a woman who served as Van Leo’s assistant, muse, model, and very probably his lover, once confided to me her belief that he’d always “wanted to be an actor.” She continued, “He was amar. He was as beautiful as the moon.” An actress who ended up with bit roles in dozens of films, Serag’s near fame was not entirely different from Van Leo’s own.

Of course, the bulk of his customers were ordinary people—a predictable parade of families, brides and grooms, passport applicants (overweight, asymmetrical, imperfect). These photographs are perhaps not altogether different from studio images anywhere in the world at that time. Witness the same devastatingly canned poses. But on occasion, fortune would strike. One day, for example, a woman came to the studio with her daughter—a long-haired girl of eight or nine—and a suitcase full of costumes to be photographed in: ballerina, sheriff, cowboy, oriental dancer. The girl’s name was Sherihan, and she swiftly became one of the most beloved icons of Egyptian television and cinema.

Or consider the case of a housewife named Nadia Abdel Wahed, who arrived at the studio one day and instructed Van Leo to take step-by-step photographs of her elaborate striptease routine. In each image, she removes a single piece of clothing. The final image in the series features her perfect, melon-shaped breasts exposed, holding a beach ball over her pubis, ready to take on the world. A five-digit phone number scribbled on the back always made her seem vividly real to me.

*

When Van Leo took time away from the studio—which was not all that often—he traveled. The list of countries he visited time and again was for the most part the stuff of humdrum bourgeois dreams: Austria, Switzerland, Italy. Album after album reveals fastidiously arranged traces of these trips—still crisp maps, ticket stubs, labels torn off bottles of wine, receipts, and photographs. The Eiffel Tower figures in many of his images, its familiar triangular thrust unchanging, even as he grew ever more haggard and jowly.

Mysteriously, Van Leo never made it to the United States, the El Dorado of his fantasies, though he went through the motions repeatedly. At the age of thirty, Van Leo initiated a correspondence with ArtCenter in Los Angeles about enrolling in classes there, having seen an advertisement for the school in a magazine. His queries are typed out neatly, requesting help with a visa and finances. “I am interested in all that photography offers,” he wrote. But as with the emigration papers he filled out at regular intervals—to the United States or to Canada— he couldn’t bring himself to leave Egypt. He was accepted to ArtCenter once, and then twice, but never went. Perhaps he preferred it that way—how could the real Hollywood have held up to his dream of it? He would never suffer that disappointment, at least.

So what do we make of this man who dreamed of leaving Egypt—Emma Bovary in Arabia—but couldn’t take the fateful step? A painfully shy fellow who nonetheless was so sure of himself that he left every scrap behind for a future museum? The shape of his life remains remarkably opaque. Sphinxlike, even. Until the end, he insisted that he had never worked with assistants. And yet we know that Ragaa Serag toiled by his side for more than a decade, a devoted Véra to his Vladimir. One childhood friend says that Van Leo’s birthplace was not Jihane, as he claimed, but a village called Deurt-Yol. In the archive, there’s a letter from a former girlfriend that refers to “our child,” but neither girlfriend nor child are mentioned again. In the same way that he removed every last imperfection from his subject’s face, Van Leo was a master of illusion.

And finally, what to make of Van Leo, the closeted queen? One can surmise that the queering of Van Leo is a game at least as old as his thirtieth birthday. Or his fortieth? As every milestone year came and went, the dashing Armenian remained, to the immense chagrin of his mother, a bachelor. (There are postcards and letters that attest to short-lived adventures with girlfriends.) In thinking about him, the question of his sexuality inevitably crops up—call it the Cavafy syndrome. Curators linger over the well-oiled physique of a muscly bodybuilder or the sensitive close-up on the face of his dashing Armenian friend, Noubar. The theatrical narcissism of the self-portraits, to say nothing of the cross-dressing, only seem to bolster the case many have made.

Van Leo used to say that he had taken many nude photographs of women, but had burned them in the 1990s for fear of being attacked by Islamic fundamentalists. This may well be true—and yet, to a discerning eye, there is something markedly abstract about the seminudes that we have seen. The women are more or less sexless, too finished to breathe with eroticism. They evoke a limp formalism and seem apropos for a photographer who was ever prone to trading in surfaces. Whether Van Leo was queer in the contemporary sense, we will almost certainly never know.

But he was without question a perpetual outsider. Van Leo was wont to bemoan the passing of his beloved Cairo, a city once populated by a cosmopolitan mélange of Jews, Greeks, Armenians, and Europeans of all stripes. The ascendance of former president Gamal Abdel Nasser, narrowly nationalist as he was, had all but destroyed that world. Van Leo would woefully evoke the plight of the Armenian Christians—people of the wrong book—to account for his lack of success. Egyptian Muslims had become overreligious and obscurantist, he said, poorly mannered and badly dressed. At the end of his career, Van Leo’s customers were mostly expatriates and the occasional tourist.

*

Van Leo stopped taking photographs in 1998. And yet, he had really stopped decades before, with the advent of color film. Color had sullied the cool elegance of black and white, he said. It was the opposite of progress. A modern pestilence, it showed people as they really were: garish, uncultivated, base. It was as if the angel of history had propelled the photographer, against his will, into an awful, tacky present. Van Leo’s was a story of betrayal—by God, Egypt, technology, style. About the pernicious effects of color film he remained agitated until the end. About this, and so many other things.

All photographs © Arab Image Foundation

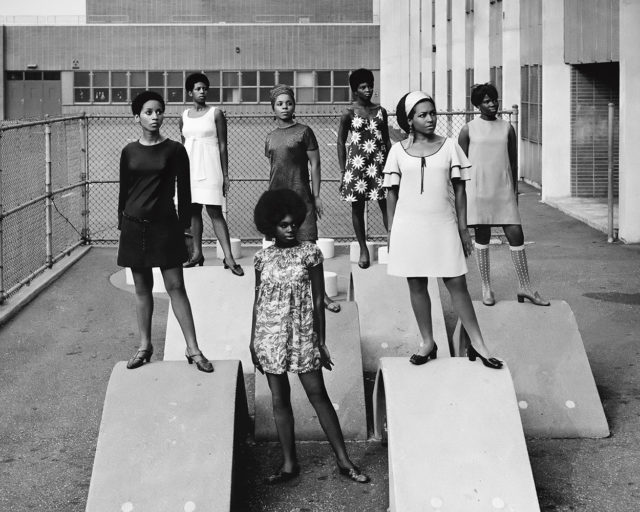

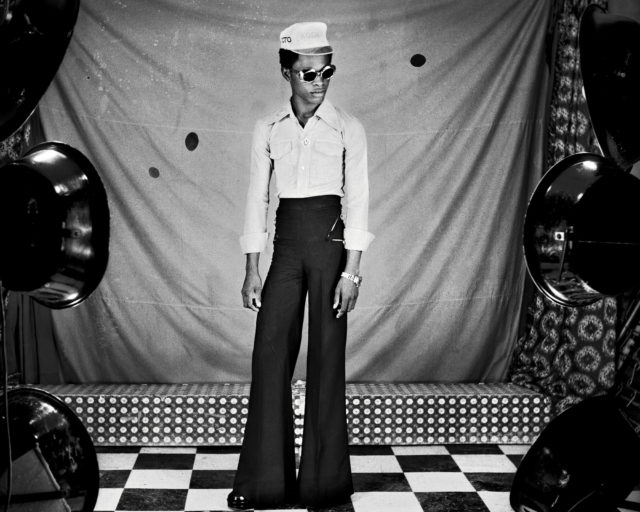

By the late 1990s, a global interest in vernacular studio photography—and, indeed, in black and white—finally attracted the world to his door. Curators such as André Magnin and Okwui Enwezor had brought about unprecedented visibility for photographers like the Malians Malick Sidibé and Seydou Keïta, and the art world began to consider studio photography a variety of fine art. Groundbreaking exhibitions, including In/sight: African Photographers, 1940 to the Present at the Guggenheim in 1996, helped create a market for such work. The following year, the Arab Image Foundation was established in Beirut to survey photographic practices across the whole of the Arab world, in all their complexity. Van Leo was one of the first photographers to figure into its growing collection. Not long after, the foundation nominated him for a Prince Claus Award, which he won in 2000. Images of him at the award ceremony reveal a bearded Van Leo in a tuxedo, beaming. Bit by bit, he began to achieve the fame he had dreamed of for six decades, or more.

The photographer died on March 18, 2002. At the time, I had been organizing a small show of his portraits at the French Cultural Institute in Cairo, and wasn’t able to visit him that afternoon as I had almost every other—bringing him the chocolate-covered prunes he liked so much and the occasional half bottle of just barely drinkable Egyptian wine. It is said that he was having an overanimated conversation with his helper, Amadou, and had a heart attack. Reduced to wearing a corset for his bulging hernia, Van Leo had been looking forward to the show, and talking a great deal about the museum to be inaugurated in his honor, which he thought would surely follow. He was waiting for us to raid the cupboard, you might say. He’s been waiting for us all along.

This essay is adapted from the book Becoming Van Leo (Arab Image Foundation and Archive Books, 2021).