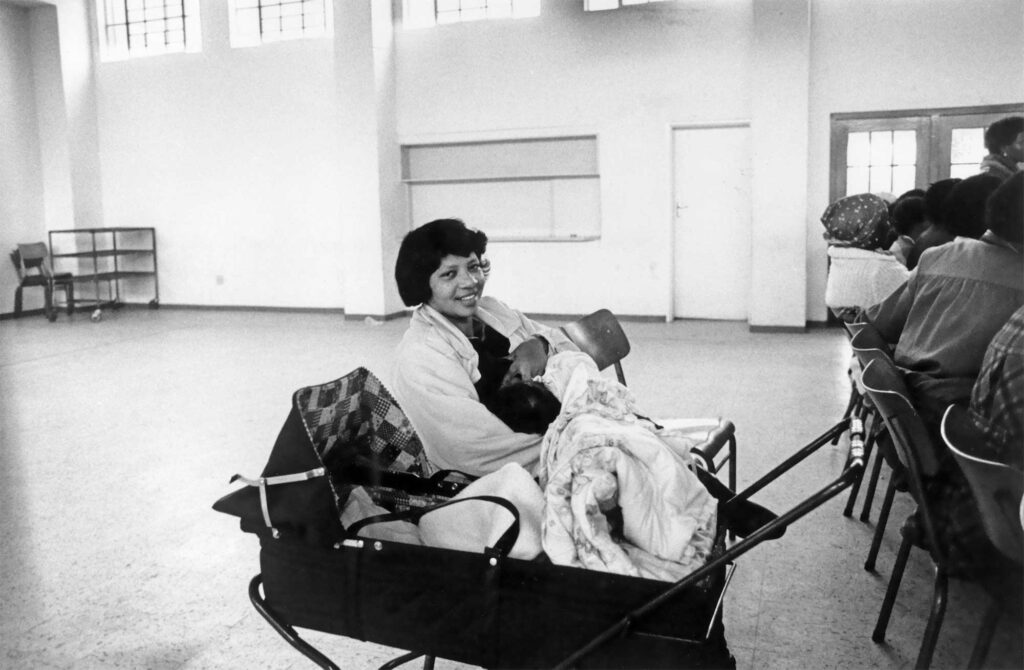

Jansje Wissema, District Six photographed before the removal, early 1970s

“How do we refigure the archives?” the late scholar Bhekizizwe Peterson once asked about the legacy of the colonial-apartheid memory project in South Africa today. Bringing to bear the multiplicity of the country’s official records—as a space of opportunity but also omission—Peterson’s inquiry invites imaginative ways to redress fixed and obscure narratives that still linger. The recent group exhibition Defiant Visions, curated by Marie Meyerding for apexart in New York, which closed in July but is still on view online, shines a light on the perspectives of women during apartheid, accentuating cracks in the archive and exposing new possibilities for these histories.

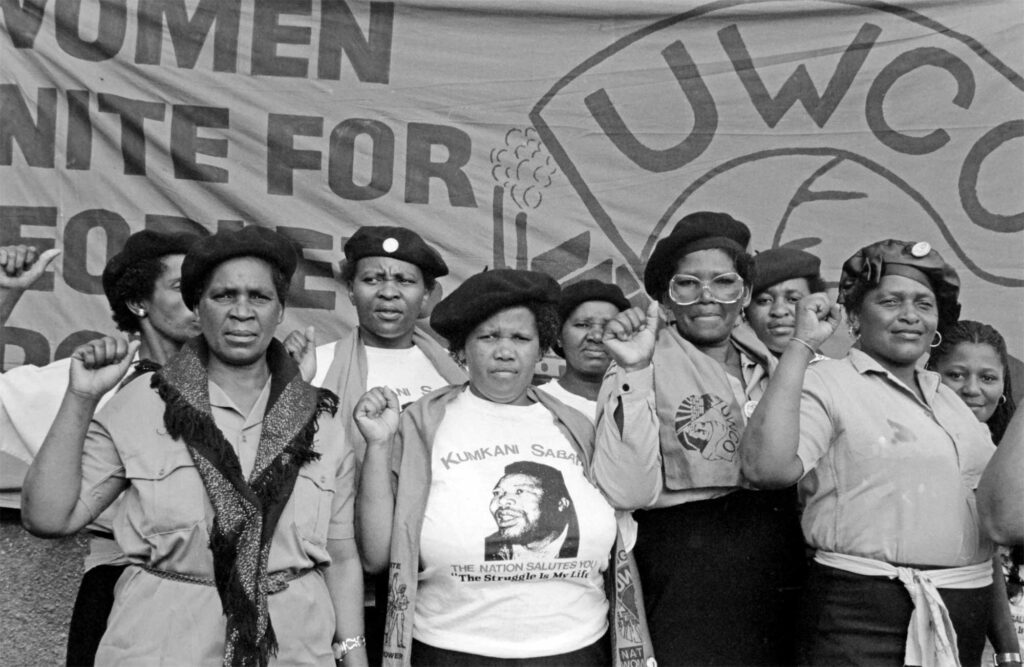

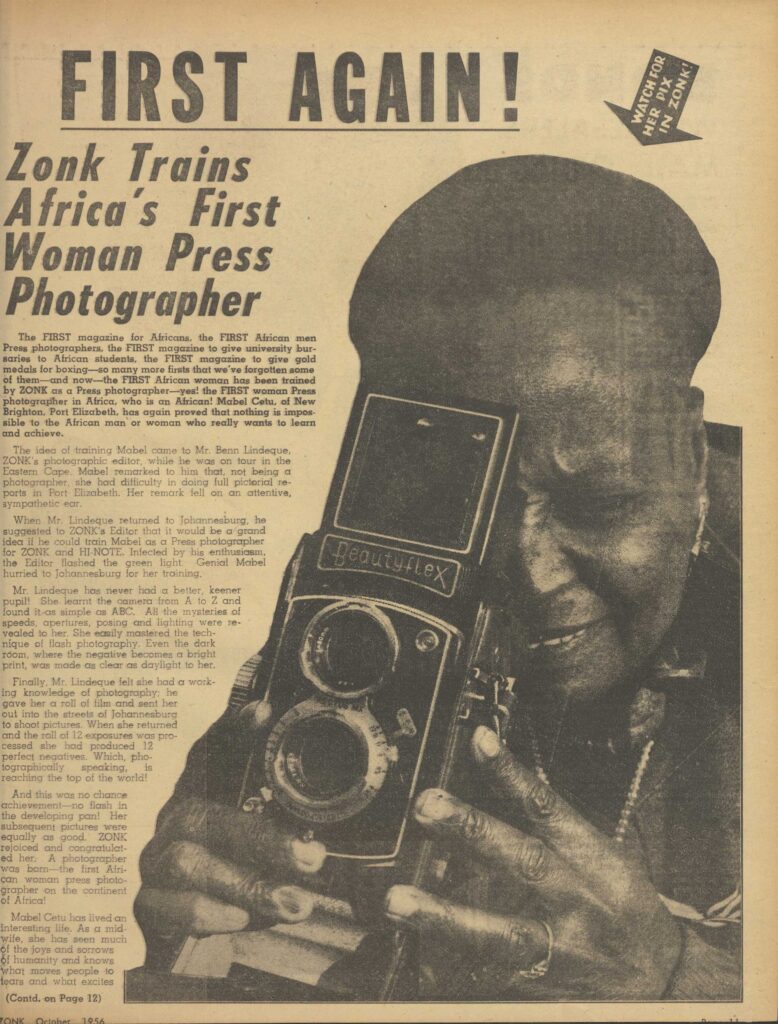

Defiant Visions brings together five photographers and two filmmakers whose divergent accounts of apartheid magnify the intricacies of women’s everyday under white-minority and patriarchal rule. It also exposes the effects of race, gender, and class structures on lives, namely Black women. The exhibition covers the 1950s to the 1990s, a time marked by resistance campaigns, an emergent field of Black photojournalism, and the shift to democracy. On view include a 1950s magazine archive spotlighting the biography and photography of Mabel Cetu, and Deborah May and Georgina Karvellas’s short documentary film You Have Struck a Rock (1981), about the 1956 Women’s March in Pretoria against pass laws for Black women.

The extensive and brutal forced removals of Black and brown people across South Africa are given nuance in Jansje Wissema’s 1970s account of District Six, a mixed-race community in Cape Town that was proclaimed as whites-only, resulting in the displacement of thousands of its residents. Meanwhile, Zubeida Vallie’s and Lesley Lawson’s photographs meditate on the quiet and more action-oriented moments of the 1980s, an era defined by increased resistance efforts against the state’s repression. Also included is a sweeping collection of Mavis Mtandeki’s images chronicling Black women’s lives in the period surrounding the country’s first democratic election in 1994.

Earlier this summer, I spoke with Meyerding about some of the artists gathered in the apexart exhibition and how their practices can help us make sense of apartheid, photography, and history-making at large.

Stefanie Qaba Jason: What prompted Defiant Visions?

Marie Meyerding: I was working on my doctoral thesis, which is on women and photography in apartheid South Africa. From the start, I wanted to make my research accessible to a larger audience beyond the small academic bubble. The title of the show is derived from Darren Newbury’s important 2009 book Defiant Images: Photography and Apartheid South Africa, which traces how photographers documented the violence that dominated anti-apartheid imagery—but this book focuses primarily on well-known male photographers. So, in Defiant Visions, I wanted to foreground the work of largely ignored women photographers and showcase their vision of everyday life during apartheid. On display is work created from the 1950s until the 1990s, which has been produced by Black and white women. Many of the resulting black-and-white images portray women and expose issues of intersectionality, which are moments where various social classifications such as race, gender, or class overlap, resulting in systemic oppression.

Apexart’s exhibition style doesn’t allow any captions to go directly with the works in the space, so it was clear to me that I needed to find other ways of contextualizing the photographs. Some of the ways in which I did this are the timeline, which you’ll encounter when entering the space, and a table and chairs, where you can take your time to read through different photobooks. I also decided to include a documentary, You Have Struck a Rock. The film is a collage of images and songs, interviews, filmed scenes, and photographs, recalling the 1956 Women’s March to the Union Buildings in Pretoria and its aftermath.

Jason: How did you become interested in this history?

Meyerding: I did my masters at the Courtauld Institute of Art in a special option course on documentary photography, film, and video in contemporary art. I wrote my master’s thesis on Candice Breitz, a South African photographer and video artist, and found that in her work she deals a lot with the representation of women. Then I asked myself if she drew inspiration from other women photographers from South Africa. Once I started doing research on women photographers working in apartheid South Africa, there was very little research that I could find, apart from some articles which were crucial for me by Kylie Thomas or Patricia Hayes. But I thought, This cannot be true; women must have been more involved with photography. That was the start of my PhD. Now I’ve submitted my PhD thesis to the Department of African Art at Freie Universität Berlin, which is the only department on African art in the German-speaking university landscape. What I can already tell you is that from the rise to the fall of apartheid, women were involved with photography.

Jason: Can we speak about the archival nature of this exhibition? I’m thinking of the black-and-white photographs, the archives presented, and some older technical equipment, like the VHS and the slide projector. What comes forward is a sort of commentary on South African archives, or maybe archives at large.

Meyerding: For me, archives are a source of invaluable information that require a lot of time to be spent in to uncover histories which are not traceable in online databases or keyword searches. Many of the women who you’ll encounter in Defiant Visions won’t appear in any keyword directories, so you really need to sit down and go through the archives and try to find out more about them. Through the presentation of the photographs or the film, I wanted to show the way the works would have been shown at the time when they were produced or distributed. Most importantly, I wanted to convey a sense of the materiality of these works, so that you get a feel for the size and the colors of Zonk! magazine, that you hear the clicking of the slide projector, that you see the film on an old TV, and also that you get a sense for the contextualization and the seriality of the photographs as they appeared and continue to appear in photobooks.

Jason: I’m also interested in the period that bookends this exhibition: 1948 through 1994. We see a timeline of the events across these dates as soon as you walk into the space.

Meyerding: Displaying this timeline was crucial for me for making Defiant Vision accessible to a larger audience, because not everyone walking into the space knows what apartheid was. It gives you a setting for the works on display and also explains some of the abbreviations visitors encounter in the photographs on display. It gives a bit more of context to people who are not familiar with apartheid and the history of South Africa.

Jason: The show makes important contributions to research on photographers such as Mabel Cetu. It also opens with Cetu’s works and archival material relating to her life. Could you share more about the recovery of these archives and your presentation of in the exhibition?

Meyerding: Mabel Cetu is considered South Africa’s first Black woman photojournalist. Though her name is often mentioned in research on the history of photography in the country, her work has not always been attributed in official archives. When I started doing some research on Cetu, I spent several days in the British Library leafing through microfilm of magazines like Zonk! African People’s Pictorial, which was the first mass-circulated magazine directed at Black people in South Africa. When I found Cetu’s photographs, I was thrilled, especially because Cetu’s work was mostly published uncredited at the time.

Jason: Mavis Mtandeki’s photographs are given critical attention in the exhibition. The show also includes the photography book Sights of Struggle: The History of the Tambo Village Women, which you coproduced with Mtandeki.

Meyerding: Mavis Mtandeki is the photographer I spent most time with over the course of several years. When I started my dissertation research, we were in touch via WhatsApp for over a year because of Covid-19 restrictions, so I couldn’t go to South Africa. We only met in person in 2021 and had numerous meetings where she showed me her archive, which included a lot of photographic prints and other materials. I was able to raise money to digitize and then publish parts of her archive. We digitized her archive with the Photography Legacy Project, led by Paul Weinberg, so her archive will be available online soon, once we have completed the metadata.

The publication Sights of Struggle includes Mavis Mtandeki’s photographs and some texts of mine that give more context to the photographs, which is the result of long conversations with Mavis Mtandeki. I’m grateful that this publication worked out, because Mavis Mtandeki and I helped each other to create a book through mutual exchange and support. Earlier this year, we had book launches in Cape Town, in the city center and Tambo Village, and Berlin. I’m thrilled to see how people engage with her work in the exhibition and through the different ways of presenting her photographs.

Jason: How did apexart’s geographical location in New York, the space, and the potential audiences encourage your curatorial vision for the show?

Meyerding: I worked with an exceptional team at apexart who offered support in making this exhibition happen and helped me get around some difficulties in producing a show in a small space, with many works, on also a small budget. What is also crucial is that apexart produces shows that are accessible both in New York City and online, enabling an international audience to see the show not only now but also in the future.

Jason: Do you have any plans to show the exhibition in South Africa?

Meyerding: No. Unfortunately, apexart exhibitions don’t typically travel to other institutions. This is also why I’m even more grateful for the opportunity of visiting the show online, because apexart produced a Matterport, where you are able to walk through the space and have a look at each work individually in quite a good quality. I was surprised at how well that’s possible. Online you will also find the exhibition essay, details of all the works that are on display, and videos of the curatorial 3D tour as well as the public programs that accompany the show. I hope that the photographers whose work is on view will gain greater attention and that the show will spark further uncovering of histories of women’s involvement with photography, be it in South Africa or elsewhere.

Defiant Visions was on view at apexart, New York, from June 1 to July 29, 2023.