The Elusive Gaze in Chanell Stone’s Self-Portraits

In her new photographs made in California and Mexico, Stone embodies a practice of Black critical looking—and shows the power of seeing and being seen.

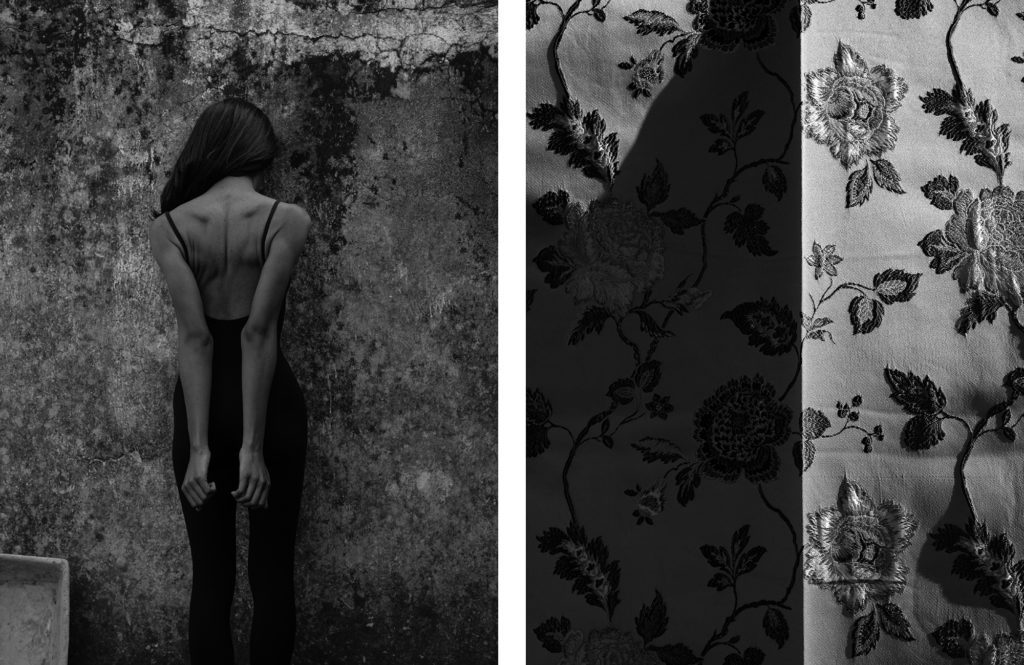

Chanell Stone, Umbra, 2022, for Aperture

Even as a technology of seeing, photography can be used to orchestrate optic negation or refusal. Present and historical forms of visibility are especially treacherous for Black women, who are pinned between the extremes of surveillance and erasure. Chanell Stone’s elegant formulation of herself as “sitter and seer,” as she said in a recent conversation, illuminates the self-circuitry of a photographic practice that reckons with this predicament through methods of withholding.

Stone’s new series, Umbra (2022), is comprised mostly of diptychs, made in Southern California, where she is currently based, and during her travels to Guadalajara and Mexico City. The establishing shots, taken in Mexico, are bereft of people and distinguishing features, giving them the vaguely familiar air of any place whatsoever. Stone appears as a solitary presence within these unmarked environments; her images are a conversation with herself. The artist has said that this flattening aspect is a way to avoid the photographic grammars of tourism, which invade the lives of daily residents and are hyperfocused on evidence of local particularity. Several of her contextualizing photographs have a kind of sfumato effect—as if they’ve been softened by a smoky haze—which accents the somnambular quality of the series. A voluminous white sheet drying on a clothesline is the one recurring object, shot alone and with Stone, and contributing to the sleepy impression of a comforting, mundane intimacy.

Stone conceived of Umbra as a conversation with images by Tony Gleaton, a Black American photographer who worked extensively in Mexico in the 1980s and 1990s, and who was known for his sensitive, dignified black-and-white portraiture of diasporic Africans in Central and South America. Another geographic connection creates a miniconstellation of global Black cultural practices: in 1969, at the National Autonomous University of Mexico, the Martinican poet and theorist Édouard Glissant claimed a “right to opacity” in the face of violently totalizing and racialized demands for transparency, particularly by “the West” towards “the Other.” Thinking alongside Glissant accentuates the shared stakes of Gleaton’s and Stone’s work in Mexico. Gleaton’s foregrounding of Black people became a way of confronting histories of colonialism and expressing his interest in cultural hybridity. Similarly, Stone’s intricate adjustments of the levers of sight in her images are a rejection of colonially inflected demands for absolute exposure.

In her previous series Natura Negra (2018–19), Stone crafted a quietly expressive visual language for her study of Black urban ecologies, situating her mesmerizing self-portraits amidst eruptions of greenery fringed by concrete. Umbra fuses this attentiveness to her self-presentation inside controlled environments with a method inclined towards opacity. Four diptychs include portraits of Stone facing away from the camera. In three of these, she is wearing an open-backed black leotard and standing almost pressed against a grainy, unevenly textured wall. She sees these images, she says, as extending her investigations into “how much you can access a photograph.” The wall, which takes up the entirety of the background, acts as a limit to sight. Stone’s proximity to the wall means that the viewer’s gaze stops where she stops.

There are echoes between Stone’s work and that of Carrie Mae Weems, who has engaged in Black feminist refusals to meet the gaze throughout her oeuvre. In The Louisiana Project (2003), Weems positions herself with her back firmly turned to the camera. Stone’s corporeal choreography is more oblique—she sometimes places herself at a slight angle rather than facing directly away—yet has a similar effect of making the self-portraits an exercise in balancing visual autonomy and personal withholding. In one diptych, Stone turns her back, possibly in a position of vulnerability: her arms are pushed back, almost as if she were manacled. This is paired with a close-up of a floral embroidered fabric, split not quite in half by the shadow created by a sharp crease, which accents the severe verticality of the work. A key difference between Weems’s and Stone’s setups is that while Weems frequently looks out at spacious expanses, Stone’s placement of herself is almost claustrophobic. She could also be turning inwards, creating a small space of refuge.

In addition to Gleaton and Glissant, Stone crafted her images in dialogue with bell hooks, particularly the late Black feminist theorist’s 1992 essay “The Oppositional Gaze.” In that piece, hooks considers the specificity of Black women’s practices of critical looking, as well as the broader potential for the act of looking to be recuperated by those marginalized by the dominant visual order: “The ‘gaze’ has been and is a site of resistance for colonized black people globally. Subordinates in relations of power learn experientially that there is a critical gaze, one that ‘looks’ to document, one that is oppositional.” Hooks assigns a particular capacity for oppositional gazing to Black women because of the ways they are positioned to consider the collusions of race and gender (as well as class) in shaping “looking relations”—the structures of power marked in the acts of seeing and being seen.

Through the mode of self-portraiture in Umbra, Stone not only claims autonomy over how she appears photographically but also safeguards herself from looking relations that would demand otherwise. Gaze averted, Stone’s interiority in these images is beautifully self-contained and unknowable. As hooks writes, “We come home to ourselves.”

Chanell Stone’s photographs were created using a FUJIFILM GFX100S with a FUJINON GF80mm F1.7 R WR lens.

Courtesy the artist