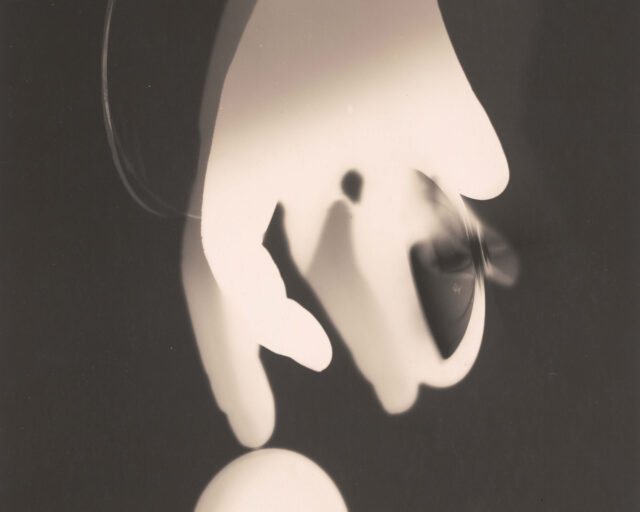

Samuel Fosso, La femme libérée américaine dans les années 70 (The liberated American woman of the 1970s), 1997, from the series Tati

© the artist and courtesy JM Patras/Paris

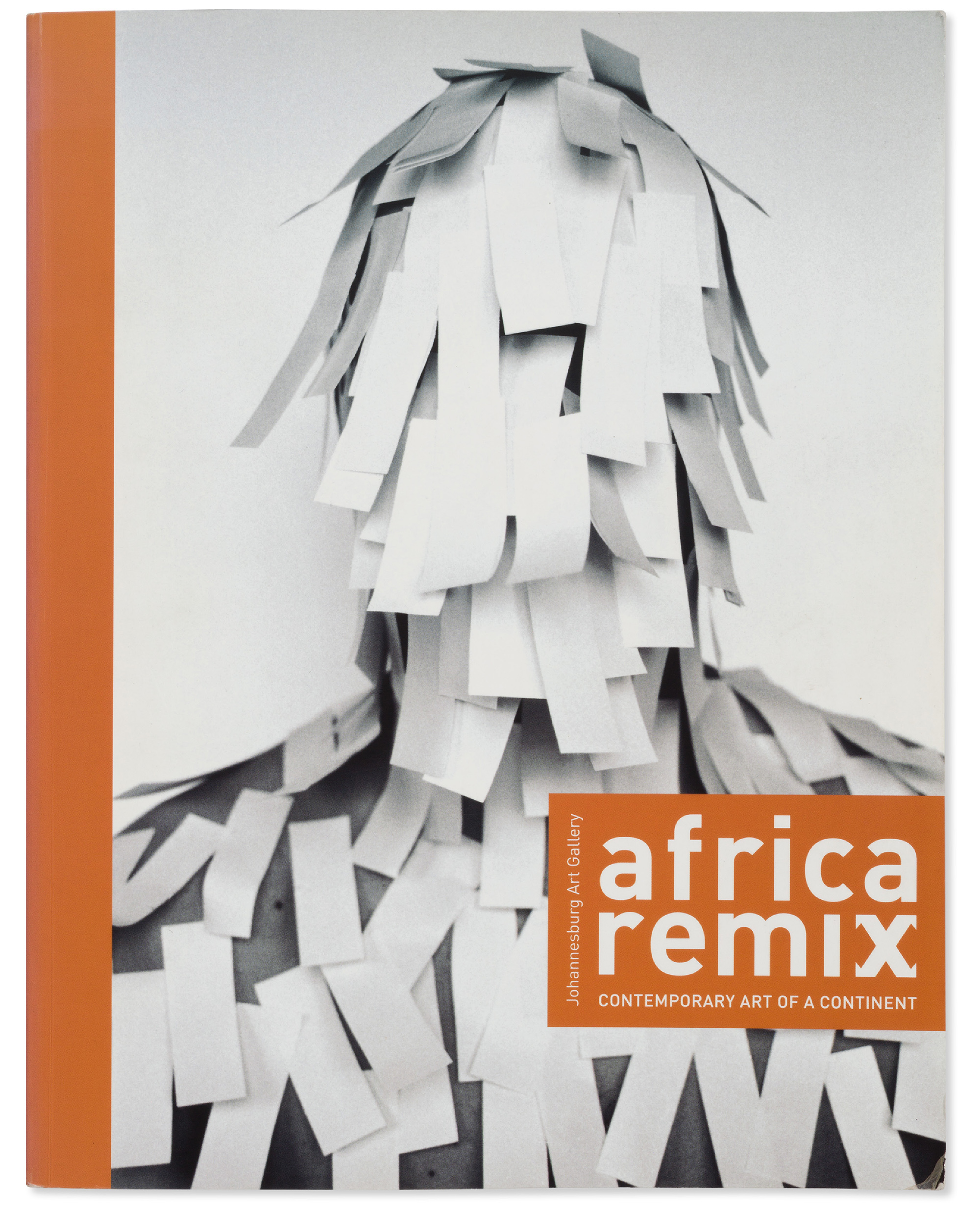

“The history of Europe in the past few centuries is an African history, whether one likes it or not,” the curator Simon Njami writes in the catalog for Africa Remix: Contemporary Art of a Continent. The landmark exhibition opened in Düsseldorf, Germany, in 2004, before traveling to London, Paris, Tokyo, Stockholm, and—amazingly, given the rarity of exhibitions about Africa originating in the global north ever travelling to the continent—Johannesburg. “Just as African history,” he adds, “is resolutely European.”

Implicit in Njami’s proposal about the continents’ entangled histories is an understanding that curatorial work is also history, that curators are also historians; like West Africa’s griots, custodians of oral histories, the curator-historian uses eccentric methods to reach provocative conclusions. Twenty years later, Africa Remix stands as a record of an era’s preoccupations and artistic statements. But does it hold up?

The catalog arrived amid a groundswell of Euro-American interest in contemporary African photography, spurred by the 1990s-era Bamako and Dakar biennials and the invaluable archival work of Revue Noire, the quarterly magazine Njami cofounded and edited. Collectively, these projects contributed to the wider reception of West African photographers like Mama Casset, Seydou Keïta, and Malick Sidibé, who were active between the 1950s and ’70s, as well as Cameroonian-born Nigerian photographer Samuel Fosso, who developed an inventive artistic practice of staged self-portraiture, beginning in the mid-’70s.

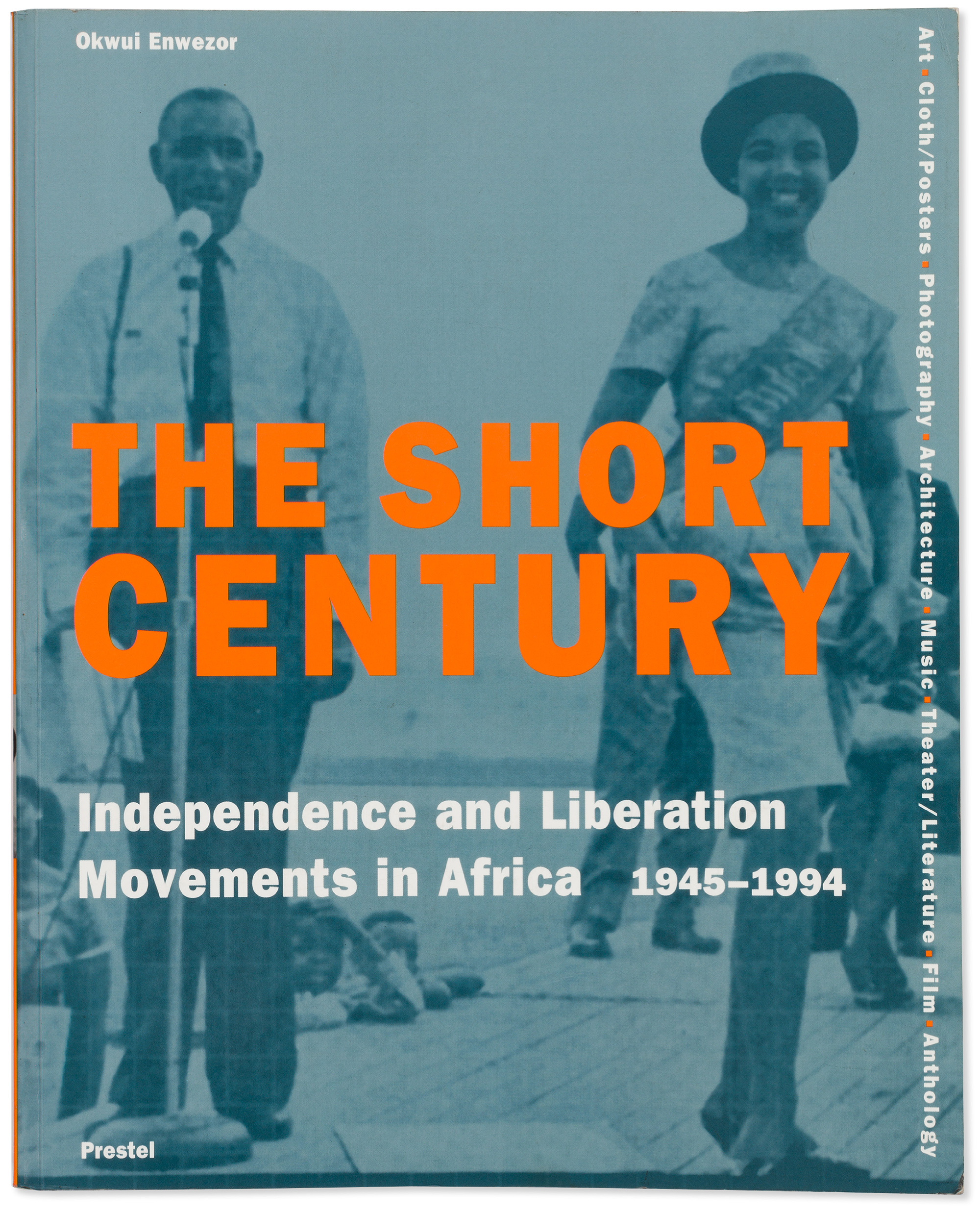

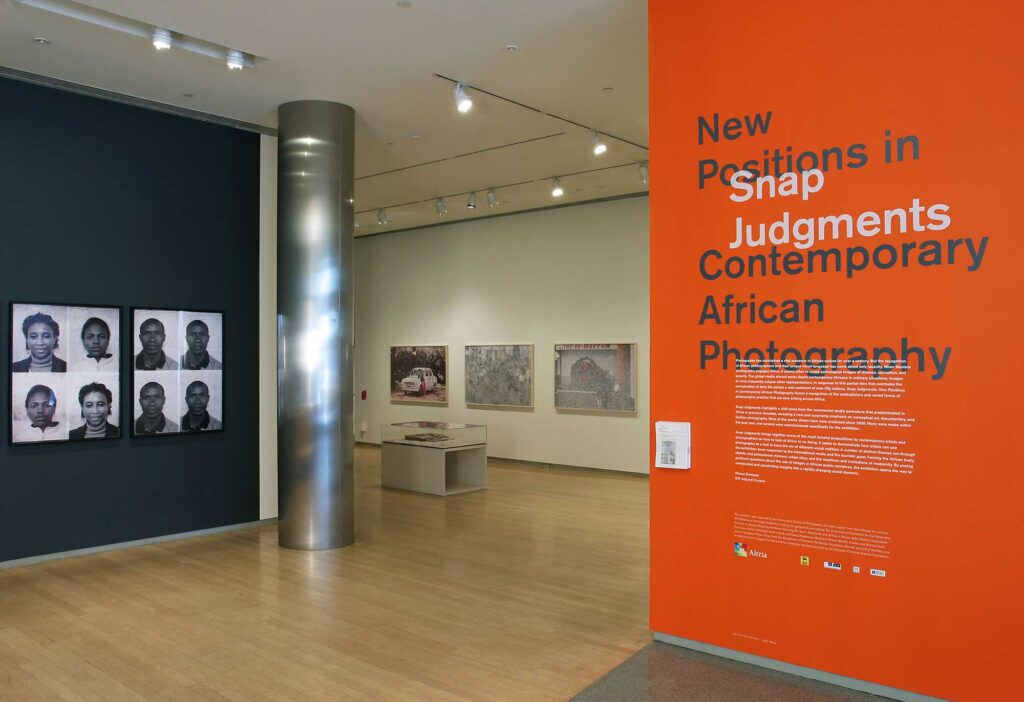

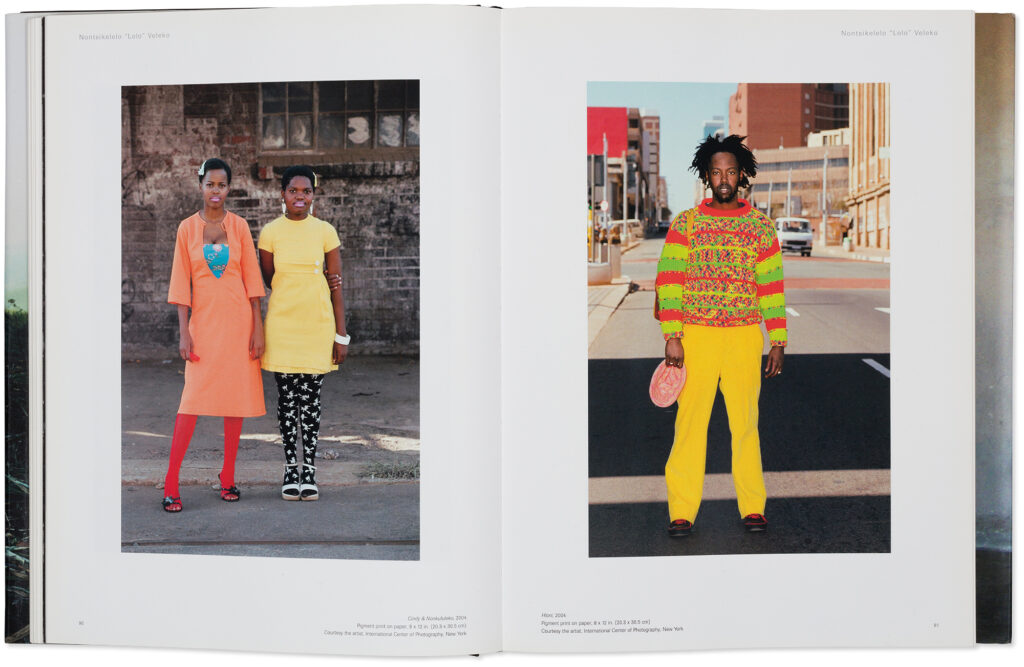

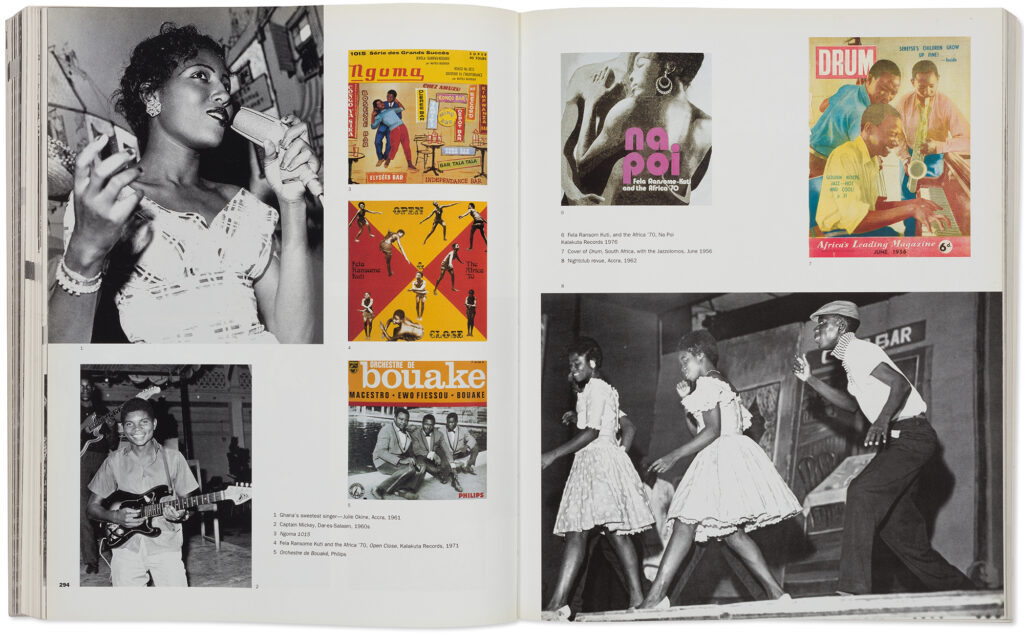

Whereas painting is now at the vanguard of African creativity, both in the art market and in museums, photography was the zeitgeist medium across Africa in the early 2000s. As in Africa Remix, it featured prominently in two similarly photo-interested traveling exhibitions, both overseen by the late Nigerian American curator Okwui Enwezor: The Short Century: Independence and Liberation Movements in Africa, 1945–1994, which opened in Munich in 2001, and Snap Judgments: New Positions in Contemporary African Photography, which launched in New York in 2006.

Less experimental and more obviously anthropological than Njami’s exhibition, The Short Century presented an overdue engagement with African modernity through work by fifty artists from twenty-two African countries. A ranging and analytical curator, Enwezor organized the historical objects around seven subject areas: modern and contemporary art, film, photography, graphics, architecture/space, music/recorded sound, and literature and theater, all linked to an historical framework. Snap Judgments was a less dialectical affair—only just. Composed of recent conceptual, documentary, and fashion photography, the show proposed that the “rigorous analytical perspective” of the thirty-four artists and one collective featured was expanding the lexicon of African art.

© International Center of Photography

Exhibitions, especially large group exhibitions, typically open with great fanfare, and then begin to weaken and atrophy, in varying increments depending on the strength of their visual arguments, until their memory can appear hazy, imprecise, in need of recall—arguably a key labor of the catalog.

Africa Remix, The Short Century, and Snap Judgments are all memorialized with doorstoppers. When they first appeared, these hefty and increasingly hard-to-find books represented important contributions to knowledge about African photography. They also updated the arguments that had been staged in two vital 1990s publications: the Guggenheim Museum’s In/Sight: African Photographers 1940 to the Present (1996), which includes a compass-setting essay by Enwezor, and Revue Noire’s Anthology of African and Indian Ocean Photography (1999), which features multiple contributions on individual photographers by Njami.

Enwezor’s and Njami’s focus on photography in the early 2000s was guided by their activism, yet their perspectives on photography and rhetorical styles also reflect their respective apprenticeships in New York and Paris. After studying politics at Jersey City State College in the early 1980s, Enwezor dove headlong into poetry (notably performing at the Nuyorican Poets Café), before emerging as an outspoken art critic interested in postcolonial identity, plurality, whiteness, and the endurance of western cultural hegemony. Njami too had literary ambitions, publishing four novels in the 1980s, before establishing himself as a rambunctious critic, who in 1991 told Senegalese filmmaker Djibril Diop Mambety, “I hate photography.”

Explaining Africa in the museums of the global north is a longstanding activity, freighted by a history of colonial encounter and subjugation.

As a writer, Njami is temperamentally and attitudinally very different from Enwezor. His rhetorical mode in Africa Remix is provocative (“Africa is a scandal . . . a continent in constant mutation . . . without doubt the kingdom of immateriality”) and philosophical (“Different forms of contemporaneity coexist without necessarily echoing each other). To resist the homogenizing tendencies of European exhibitions on Africa art, Njami organized the sculpture, video, installation, and painting into three thematic groupings: identity and history, body and soul, city and land. A quarter of the artists on view used photography as their primary medium; yet, strangely, Njami barely discusses photography in his essay.

Enwezor, particularly in Snap Judgments, is far more persuasive about the evolution and arc of African photography at the start of the new century. Noting the increasingly analytical mode of recent work, he writes, “the new position the artists adopt engages broader spheres of interest such as landscape, urban studies, performance, portraiture, and documentary, differing from earlier approaches.”

History informs the thinking of both Njami and Enwezor as curators, and an historical perspective is ever-present in their work as writers (“To broach contemporaneity in Africa,” writes Njami in his Africa Remix essay, “inevitably leads to a re-reading of history”). Their cosmopolitan ethos and genre-spanning approaches were shaped by the presentation of Africa in Paris and New York, in particular “Primitivism” in 20th Century Art: Affinity of the Tribal and the Modern (1984), a controversial New York exhibition pairing classical African art with examples of high modernist European painting and sculpture, and Magiciens de la terre (1989), an equally charged Paris exhibition that juxtaposed established Western artists such as John Baldessari and Louis Bourgeois with a broad constituency of non-Western folk artists, crafters, shamans, priests, and hard-to-classify visionaries like Frédéric Bruly Bouabré and Bodys Isek Kingelez (each of whom would have posthumous solo exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art, New York).

Showcasing and explaining Africa in the museums of the global north is, of course, a longstanding activity, freighted by a history of colonial encounter and subjugation, but also informed by different traditions of art scholarship and literary style. Njami, who was born in Lausanne, Switzerland, thinks and writes in the intellectual mode of Baldwin, Sartre, and Senghor, balancing activism and rhetoric with an acute literary style, while Enwezor—a refugee of the Biafran War, a circumstance mentioned in his Snap Judgments essay—was a quintessential New York intellectual gripped by the ideas of Agamben, Derrida, and Glissant, philosophers who informed his logical precision and ethical ambition as a writer.

Njami is far more playful and epigrammatic than Enwezor, who jettisoned his argumentative style of the early 1990s in favor of method, reason, and flashes of lyrical brilliance that connected his practice to the history work of griots. In his essay in Short Century, for instance, he quotes a passage from Martinican writer and politician Aimé Césaire’s epic poem, Notebook of a Return to a Native Land (1939), when a mutiny on a slave ship causes it to crack apart and reveal the “ghastly tapeworm of its cargo.” In response, he writes: “Like the cracking of the slave ship, the relationship of African modernity to Europe’s construction of the universal subject is both a critique and modification, a rip in the body of the colonial text.”

Catalogues are opportunities not only to read but also to look. Snap Judgments features an untitled 2003 portrait of a cane worker by Zwelethu Mthethwa on its cover. A leading figure in South Africa’s early post-apartheid photography scene (evidenced by his appearance in Africa Remix and The Short Century, too) Mthethwa was incarcerated in 2017 for a violent murder committed four years earlier. By then, African photography’s critical moment had also seemingly passed, although the Rencontres de Bamako, the biennial of African photography established in Mali in 1994, continued intermittently to present exhibitions of photography, as did spaces such as the Centre for Contemporary Art in Lagos and RAW Material in Dakar. Still, figurative painters like Marlene Dumas and Kerry James Marshall, who appeared in Enwezor’s 2015 Venice Biennale, defined the new zeitgeist.

Courtesy Stevenson, Cape Town and Johannesburg

Only two other artists appeared in all three exhibitions: Zarina Bhimji, a Ugandan photographer based in London, and Moshekwa Langa, who like Mthethwa is South African. For a period in the 1990s and early 2000s, South Africa was a site for ambitious exhibition making. Africa Remix opened at the Johannesburg Art Gallery, a century-old municipal museum, in 2007. The date is at the midpoint between Enwezor’s stellar curatorship of the second Johannesburg Biennale, in 1997, and the 2015 presentation in Johannesburg of his exhibition Rise and Fall of Apartheid: Photography and the Bureaucracy of Everyday Life, which, like Snap Judgments, originated at the International Center of Photography.

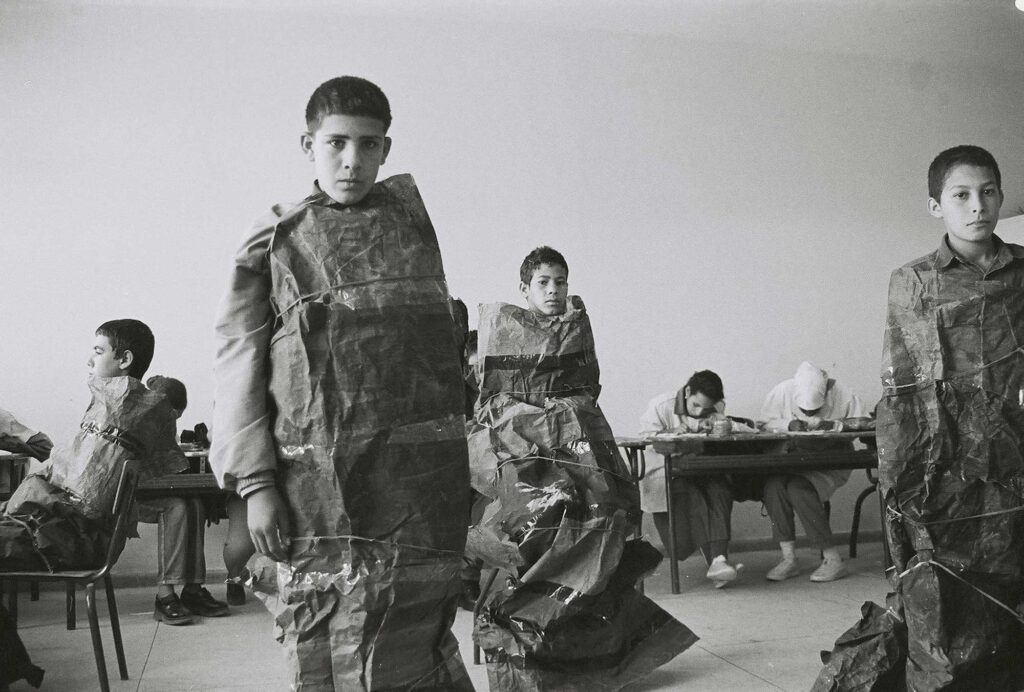

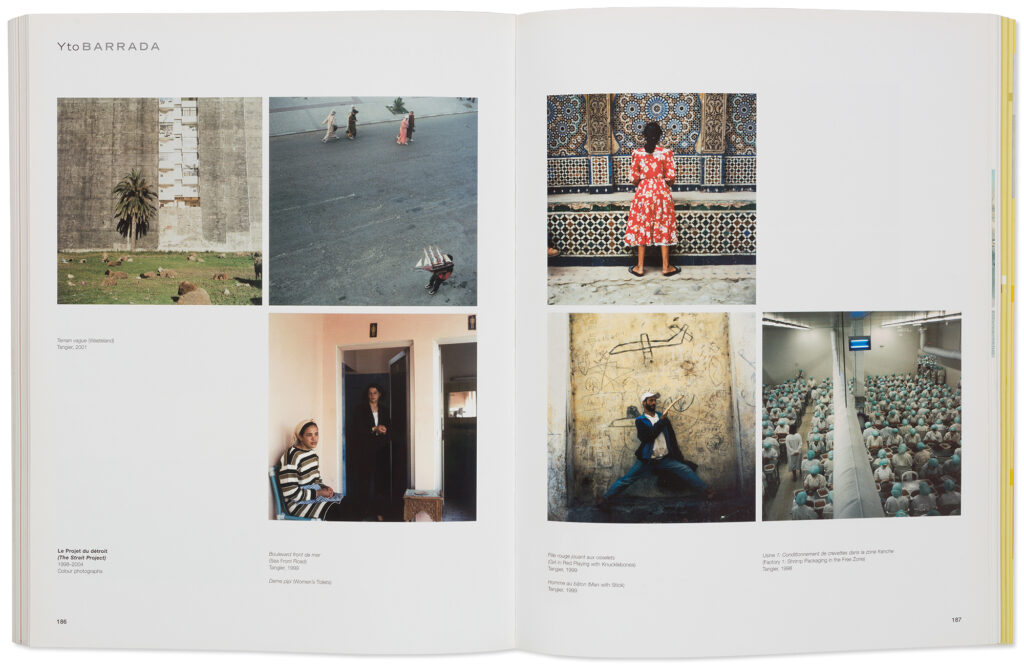

For South Africans, Africa Remix presented a rare opportunity to see the work of local photographers in conversation with works by the likes of Akinbode Akinbiyi, Yto Barrada, Hicham Benohoud, and Jellel Gasteli. It also provided an opportunity to test the veracity of the negative reviews Africa Remix generated in London in 2005. Brian Sewell, a neoconservative critic in the tradition of Hilton Kramer, described Njami’s exhibition as a “wretched assembly of post tribal artifacts”—and much worse. Perplexed by Njami’s thematic focus on urban Africa and strong preference for lens-based media, Jonathan Jones told Guardian readers, “Africa Remix misdescribes the continent.” The exhibition represented the view of “city-dwelling elites” Jones reported back to his constituency of, yes, city-dwelling elites.

Courtesy the artist

Although it remains the least urbanized continent on the planet, in 2005, Africa had forty-three cities with more than one million inhabitants. Writing a year earlier in his magnum opus, For the City Yet to Come: Changing African Life in Four Cities (2004), urban theorist AddouMaliq Simone argued: “In city after city, one can witness an incessant throbbing produced by the intense proximity of hundreds of activities: cooking, reciting, selling, loading and unloading, fighting, praying, relaxing, pounding.”

Both Enwezor and Njami were keen to show this proximity. In his introduction to the section of photos grouped under “city and land” in Africa Remix, Njami leans into this cliché of a rural continent (“The city is a recent concept in Africa”), and then promptly detonates it by emphasizing the extraordinary volume of work about African cities (“Showing the city is never gratuitous”). Enwezor too was interested in the metropolitan subjectivity and focus of new African photography. “A large selection of Snap Judgments brings together studies of urban sites,” writes Enwezor, who was interested in how the work of Barrada, Kay Hassan, and the collective Depth of Field (founded in 2001 by Nigerians Kelechi Amadi-Obi, Uchechukwa James-Iroha, Toyin Sokefun and Amaize Ojeikere, the son of studio photographer J.D. Okhai Ojeikere), among others, addressed “modes or urban living and the changes that shape the postcolonial metropolis.”

All book photographs by Mia Thom

Africa Remix’s arrival in Johannesburg inspired the production of an updated (and also more affordable) edition of the three earlier catalogs published in German, English, and Japanese. Samuel Fosso’s vibrant color self-portrait, The Chief Who Sold Africa to the Settlers (1997), features on the cover of both the English and German editions, as well as in the mosaic of images used for the cover of the Japanese edition, while a black-and-white self-portrait from Moroccan photographer Hicham Benohoud’s series Version Soft (2003) adorns the later version, which includes new essays by philosopher Achille Mbembe and JAG director Clive Kellner. “This is the first time a major exhibition of contemporary African art will be held in Africa,” writes Kellner in a preface. This is not true. What he meant to say was that it was one of the first times a major Western exhibition of any art, let alone African art, visited the continent.

“There have been many, in recent years almost too many, great exhibitions of African art in Europe and in America,” writes Frank McEwen, the charismatic and worldly director of Rhodes National Gallery (now National Gallery of Zimbabwe), in the catalog accompanying the First International Congress of African Culture in 1962. Held in Harare, the accompanying exhibition explored ideas rehearsed in “Primitivism” in 20th Century Art and Magiciens de la terre, more than two decades later. It was high time, ventured McEwen, “that African art were shown more often in Africa, and reclaimed culturally by its creators.”

© Santu Mofokeng Foundation and courtesy Lunetta Bartz, MAKER, Johannesburg

That possibility was not an abstraction. In 1958, Edward Steichen’s large-scale photo exhibition, The Family of Man, was presented in Johannesburg. Photographer Peter Magubane, whose early Drum-era work is illustrated in the catalogue for The Short Century, attended the exhibition. “I began working very, very hard to try and reach the standard of those pictures that I saw,” Magubane told photographer Ken Light. Magubane’s statement is a caution against lionizing the role of curators simply or only as historians involved in the production of revisionist texts. Exhibitions are embodied and experiential; seeing an exhibition in person, more so than reading about its ambitions after the fact, is a privileged occasion to pause, think, maybe learn, possibly even aspire.