The Nun Who Became a Pop Art Activist

The works of artist, educator, and social justice activist Corita Kent are packed with slogans and scripture. Her silk-screen posters from the 1960s and ’70s crackle with the energy of a time of social unrest. She pulled text and images from advertising and media, recombining them into compositions reflecting on the Civil Rights and peace movements.

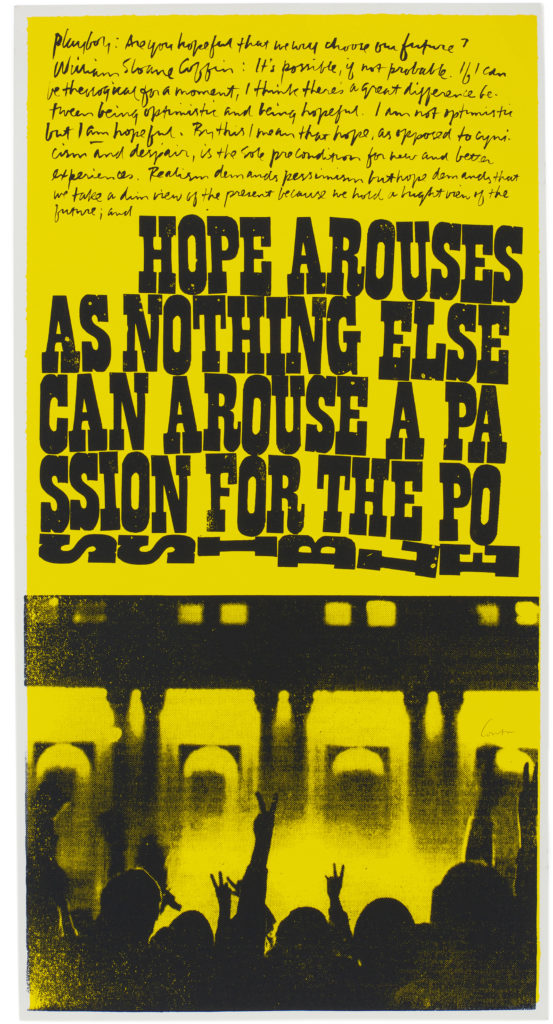

“GET WITH THE ACTION,” demands a 1965 silk-screen titled for emergency use soft shoulder, its primary colors reminiscent of Wonder Bread packaging. “HOPE AROUSES AS NOTHING ELSE CAN AROUSE A PASSION FOR THE POSSIBLE,” says another piece from 1969 in black block letters on a bright-yellow field. Kent’s Pop art style is often compared to that of Andy Warhol— whose paintings of soup cans she saw in 1962 at Ferus Gallery in Los Angeles—often as defense of her legitimate claim to be part of the canon. Yet while the more famous artist traded in a cosmopolitan deadpan, Kent’s practice reflected her Catholic beliefs and humanity.

Courtesy Corita Art Center, Immaculate Heart Community

Kent joined the Sisters of the Immaculate Heart of Mary in Los Angeles at the age of eighteen. She was a teacher and chair of the Arts Department at Immaculate Heart College until she left the order in 1968, and she continued to make art until her death from cancer in 1986. It was during the mid-sixties, on the heels of Vatican II and the modernization of the Catholic Church, that Kent’s political affinities deepened, aligning with protests against the Vietnam War and the countercultural critique of consumerism.

In 1967, Kent was on the cover of Newsweek magazine with the headline “The Nun: Going Modern,” but to reduce her to religion and aesthetics overlooks her role as an educator eager to change how people see the world. As mid-twentieth-century life around Kent’s religious community accelerated, she advocated in her teaching and practice for “slow looking,” according to Nellie Scott, executive director of the Corita Art Center (CAC), the organization that preserves Kent’s legacy. Kent’s personal papers are archived at Harvard, but the CAC manages the collection of artworks, ephemera, and objects from her time at the Immaculate Art College, which includes roughly fifteen thousand 35 mm slides of photographs taken by Kent and her camera (mostly between 1955–68).

Courtesy Corita Art Center, Immaculate Heart Community

One of the most striking works in the collection is a photograph depicting a procession of nuns and students in flower garlands carrying banners and hand-painted signs. Taken in 1964, it looks like it could be a protest, but actually, it is of the Mary’s Day festival at the college.

Photography was essential to Kent’s work. She would photograph ads and newspapers, billboards and signage, then incorporate text and graphics into her silk screens using an overhead projector, which often distorted or recontextualized the image, to create stencils. “She flattens out images, because she is thinking ahead to how to translate to a screen print,” says Olivian Cha, CAC collections manager and curator.

The camera was also a part of her teaching—a way to frame and reflect.

“When I think of her photography practice and how it informed her larger body of work, I often reflect on the walks she took with her students throughout Los Angeles using a ‘viewfinder’ as a tool,” says Scott, referring to the pieces of paper punctuated with small square apertures or the blank 35 mm slides used in class. “The finders function similarly to a camera lens, to help examine details within a larger visual field. Rather than the act of trying to take in everything at once, this practice encourages the eye to appreciate the distinct parts within a whole picture. This type of assignment requires faith in being truly present and often leads to a discovery in the everyday that was previously overlooked.”

Courtesy Corita Art Center, Immaculate Heart Community

Kent’s technique, however, is imperfect at times. In the CAC archive, there are pictures clearly taken out of the passenger window of a car, hasty shots of passing building signage. (Kent didn’t know how to drive.) The photographs taken through the windshield of La Brea Avenue or Sunset Boulevard have an affinity with the work of architect Denise Scott Brown—who also, at times, photographed from a moving car and trained her lens on the clutter of late-1960s signage. Both Kent and Scott Brown used photography as a means to fulfill a grander mission: for Kent, peace and social justice; for Scott Brown, research for Learning From Las Vegas (1972), the canonical text of postmodern architecture written with Robert Venturi and Steven Izenour.

Both Kent and Scott Brown also share the unfortunate predicament of struggling for their own legitimacy in the canon. Scott Brown has spent the later part of her career fighting to be seen as an equal partner to Venturi. Kent, while well recognized in her time and even now compared to well-known Pop artists, is not a yet household name. The CAC is searching for funding to digitize the dozens of binders that constitute her slide archive. “It’s a large endeavor,” notes Cha, “but we are excited to be able to make those images available for scholarship.”

Courtesy Corita Art Center, Immaculate Heart Community

Kent photographed the East Hollywood neighborhood around the Immaculate Heart College, located at the corner of Franklin and Western Avenues. The serigraph studio was across the street from the school in an ordinary storefront. (That Franklin Avenue building still stands, but is currently threated by demolition, and the Corita Art Center is campaigning to designate it a historic landmark.) Behind it was the Market Basket supermarket, a seemingly favorite subject. Kent captured Brillo boxes (à la Warhol, perhaps) and stacks of Gleem toothpaste. She shot the white lines of parking-lot stripes and a rental-car advertisement plastered on a bus bench. “I don’t know if she ever considered photography an art form in itself,” says Cha. “It was a means to an end. She never printed the photographs.” Although the images were never meant to be standalone compositions, they offer insight into Kent’s methodology—her eye, her time, and her city.