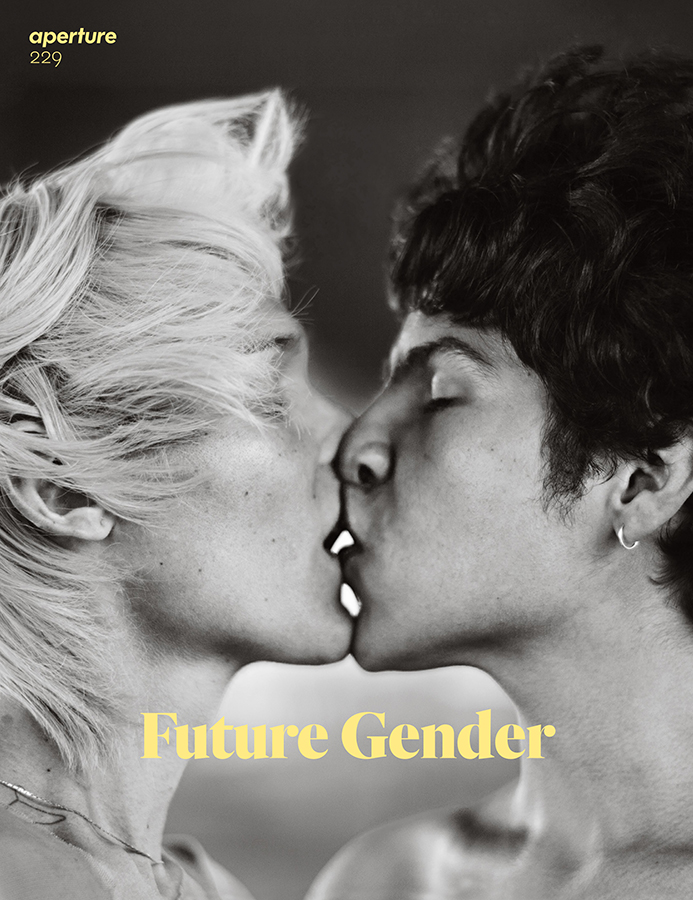

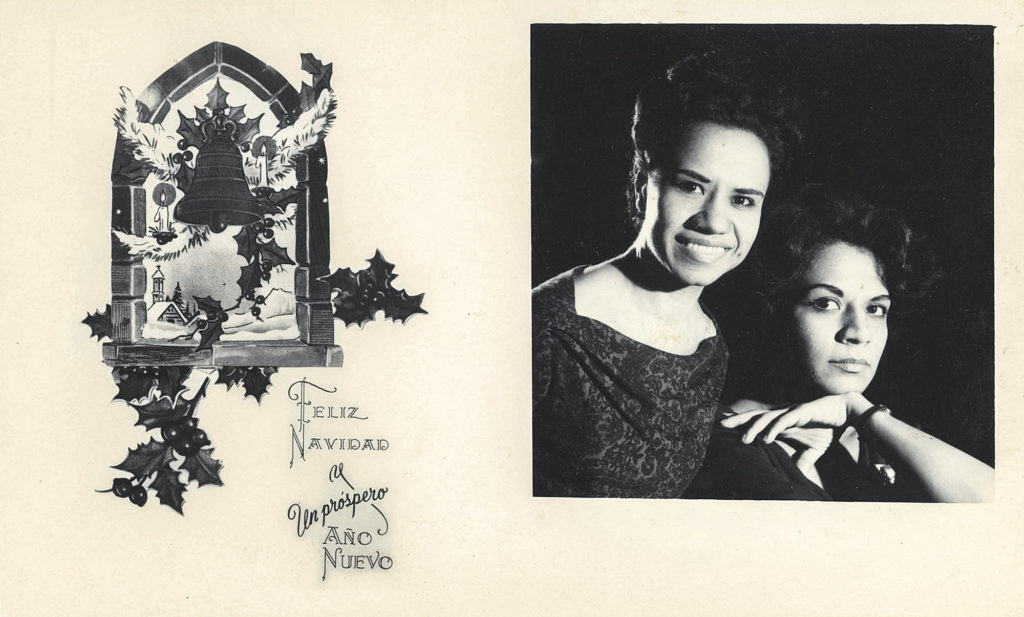

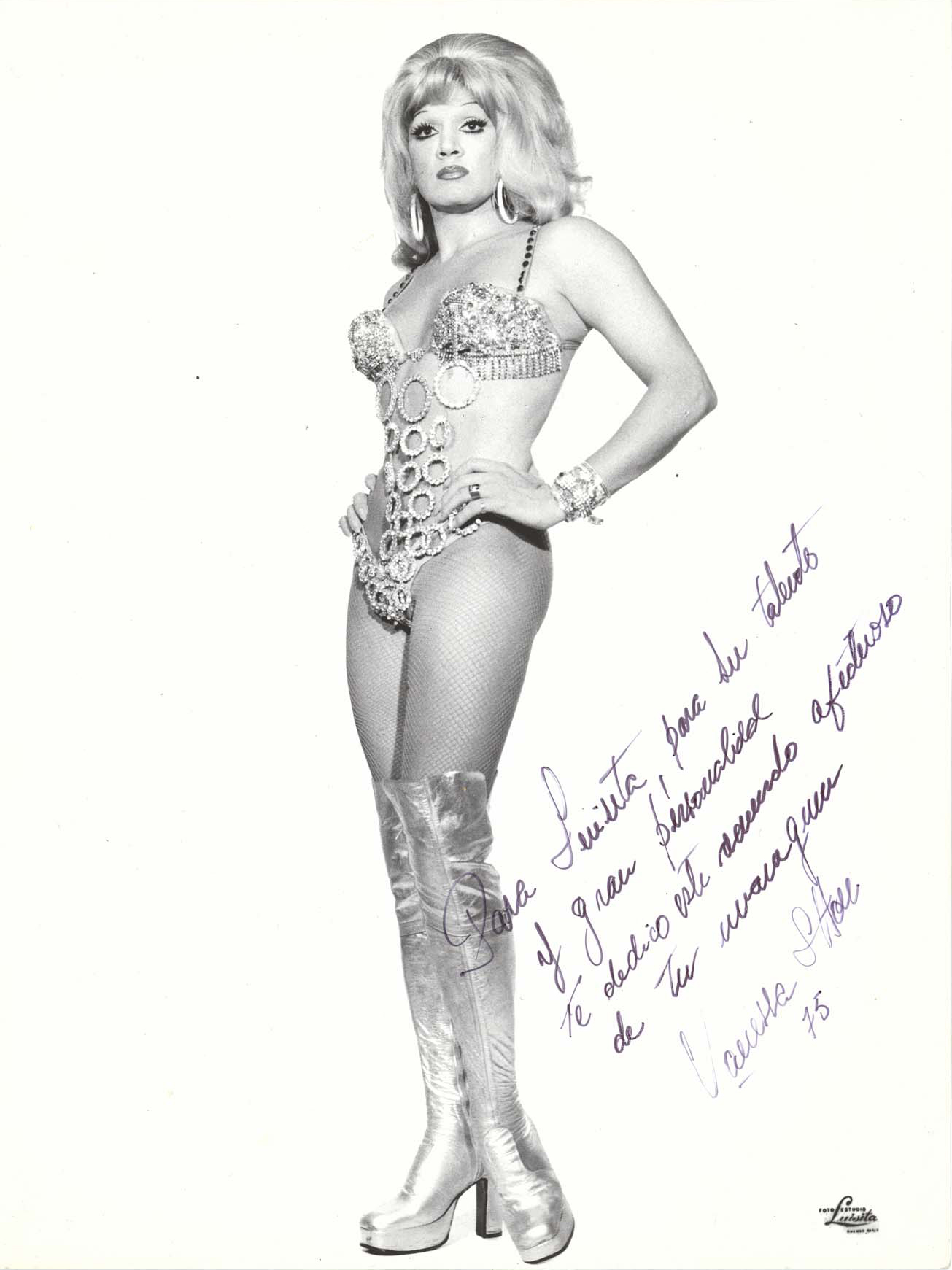

Autographed photograph of Argentine actress Zulma Faiad, 1972

Foto Estudio Luisita opened its doors in Buenos Aires in 1958, after Luisa Escarria moved to Argentina’s capital from Colombia with her mother and aunt, escaping La Violencia, a devastating armed conflict that scourged her home country for nearly two decades. Luisa’s sister, Chela Escarria, who also played an integral role in the studio, had arrived the year before. Introduced to photography at a very young age, Luisita and Chela were soon running a successful studio out of their small home on Avenida Corrientes. In the two decades that followed, being photographed their the studio became a rite of passage for the makers of the golden age of theatrical revue, including actors, dancers, comedians, singers, contortionists, sex symbols, and the occasional prize-winning canary or crowned adorned dog.

If the studio continued to thrive through the political and economic upheavals that marked Argentina during the 1970s and ’80s, it was the advent of the digital age that led to its closure in 2009. That same year, cinematographer Sol Miraglia, who is now the custodian of the studio’s archive, met the sisters and quickly became a presence in their lives. Over the next ten years, Miraglia sorted through roughly five decades of material, which might have met a very different fate if not for her fortuitous intervention. In 2018, working with her partner, Hugo Manso, Miraglia directed the documentary Foto Estudio Luisita, which offers a glimpse of her time with the sisters and her experience assessing the forty thousand images contained in the archive.

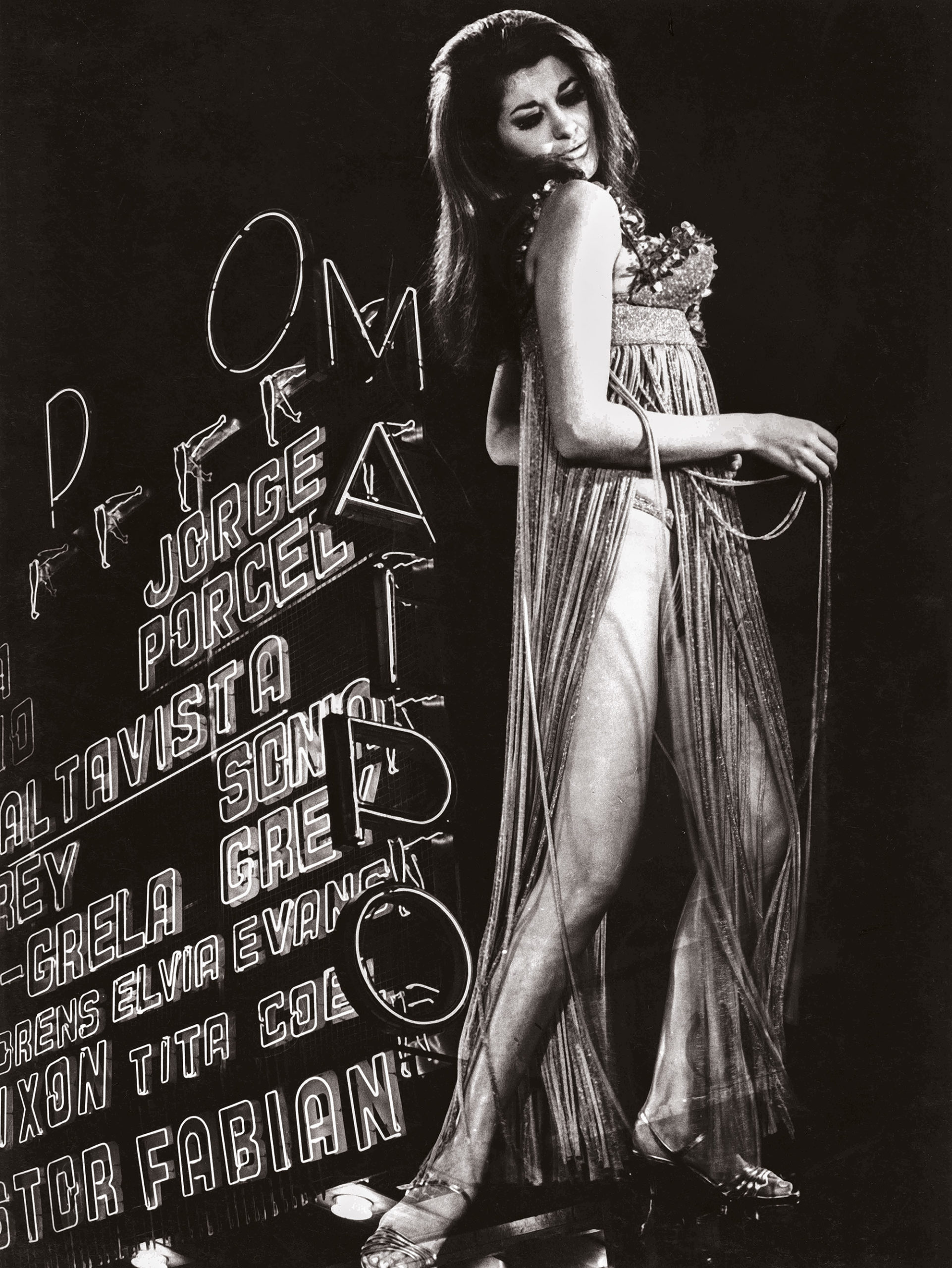

Although the Escarria sisters produced some of the most iconic images of Argentina’s popular culture, the commercial nature of their work has, until recently, denied them a place in the history of photography. The efforts made in the last decade to rescue the sisters from oblivion culminated in the exhibition Temporada Fulgor: Foto Estudio Luisita at Museum of Latin American Art of Buenos Aires (MALBA). Curated by independent curator Sofía Dourron in collaboration with Miraglia, the exhibition immersed viewers in the world of the sisters and included behind-the-scenes images that had never left their home on Corrientes before. The show featured photographs documenting the revue scene between 1964 to 1980—the largest body of work preserved by the sisters. Those familiar with the celebrities represented in them may have connected with the material on a more intimate level, yet even without that knowledge, the affective force of the images has a broad reach beyond Argentina. While the future of the archive is still being determined, the work done to bring it back into the spotlight has allowed for a critical reassessment of the importance of the studio, the women who ran it, and all the people who passed through its doors.

Earlier this year, I spoke with Miraglia and Dourron about the studio’s legacy and the role of the Escarria sisters as bearers of cultural memory.

Marina Dumont-Gauthier: How did you become interested in Foto Estudio Luisita?

Sol Miraglia: In 2009, I started giving Photoshop classes in a camera shop on Calle Libertad. It was your typical carpeted office, located in the epicenter for the sale of photo supplies in Buenos Aires. I was nineteen years old and enrolled in photo school. We were nearing the end of the year when Elsa, the shop owner, hung up a laminated calendar that read “Stars of Buenos Aires – Foto Estudio Luisita.” Appearing full-length on a background of blue stars were some of the country’s biggest celebrities, like [comedian] Alberto Olmedo and [actresses] Moria Casán and Tita Merello. I was immediately struck by it.

“You have to meet her,” Elsa told me. And as luck would have it, Luisita came to the store only a few days later, looking to buy a flash. With the excuse of having a photojournalism gig, I was invited to her house. I remember how I stopped in my tracks as I entered. Hanging on the living room walls, as if guarding both space and time, was a sea of photos of Argentina’s greatest vedettes. It was like entering a 1970s time capsule. I had a strange feeling that is difficult to describe, but it was the same rush of emotions I felt when I saw the calendar in the store for the first time.

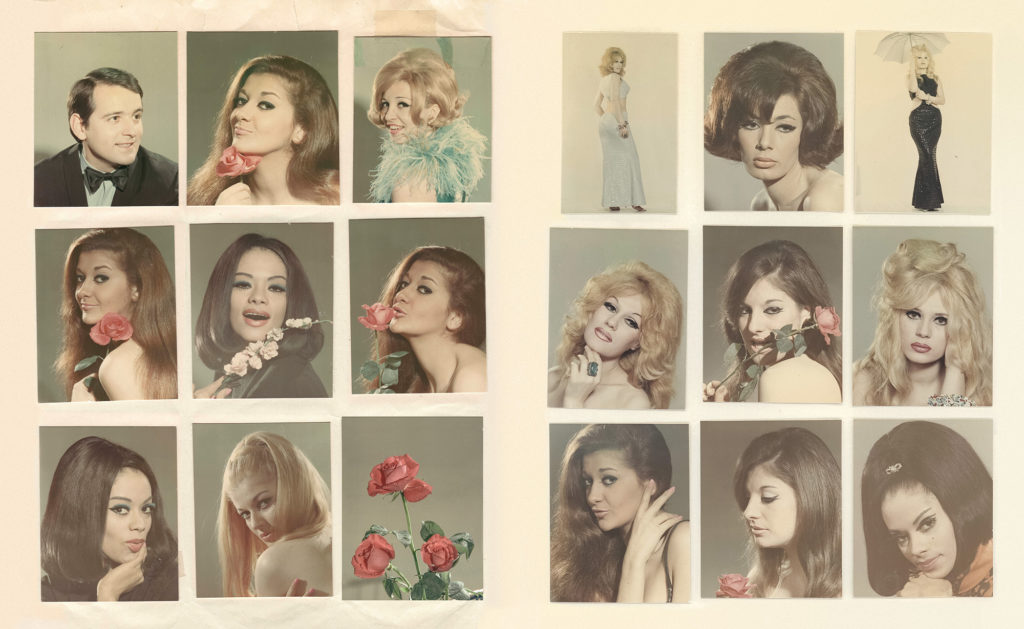

Luisita started to show me albums of vintage photos, many of which were signed and autographed for her, as if legitimizing her work to me with this display of signatures and dedications by some of the best-known personalities of the day. Completing the scene were various boxes throughout the room with labels such as “nudes” or “exteriors.”

Going through the boxes, I asked her what had happened to all the material: the negatives, other copies, etc. She told me that a fair amount had been thrown away, mainly due to a lack of space, but also because many of the faces that graced the photos had “left the race” or died and would not be coming back to request additional copies. That was a central part of the studio’s financing beyond photo shoots: months and even years after the photos had been taken, people were still ordering new copies by the dozens.

From that time onward, every Friday after work, I would visit their home/studio at the corner of Corrientes and Uruguay and spend time with Luisita and Chela, looking at old photographs, sharing meals and anecdotes, until it got late and they would kick me out! Through a mix of candor, transparency, humility, and tenderness, what was to become one of my life’s most defining friendships began. And it was that friendship that would give me the impetus to create the documentary.

Dumont-Gauthier: Can you tell me about the workings of the studio and the dynamic between the sisters?

Miraglia: They had very different roles from the beginning, all the way back to when they were operating the studio in Colombia. Though the studio bears Luisita’s name, ego played no part in that decision. Luisita described her and her sister as a team, each having a necessary and complementary role. Chela was the laboratory technician extraordinaire: She would process, copy, and retouch negatives. She was also in charge of lighting the photoshoots, scheduling appointments, and receiving the guests that passed through the studio’s doors. Chela would always say, “I’m the dark side of the moon.”

Luisita, on the other hand, was a very shy and sensitive person. Just over five feet tall and soft-spoken, she had a natural ability to make people feel at ease, which I think was vital given that many of the sitters would pose almost fully naked. In that regard, the setting of the studio in the heart of their home was a major plus, since it made the space feel warm and intimate. It was as much a studio as it was a home: they would set up the studio in the living room every day, and visitors had to go through Luisita’s bedroom to access the washroom. Their mother, Eva, who lived with them until she passed away in 1989, would welcome clients with tea and arepas and became a beloved staple of the studio. All in all, Luisita and Chela worked in silent and perfect coordination and did everything together, inside and outside of the studio.

Dumont-Gauthier: You spent ten years getting to know the sisters and their archive. What led you to turn this experience into a documentary?

Miraglia: The sisters wanted me to throw away all the negatives. They said no one was going to ask for their portraits anymore and that if they weren’t dead, they would prefer digital photos. Given this sentiment, I realized that it would be very challenging to convey the incredible contents of the archive in an exhibition or book. So I began thinking of ways to share what I felt was both a story and an archive that simply couldn’t fall into oblivion. That’s how I started to bring my camera and tripod to the studio, slowly and silently capturing the sisters in their daily routines and recording our conversations. It was around that time that I met Hugo Manso, a filmmaker who would become my partner. Together we filmed the sisters for almost four years, from 2014 to 2017, not knowing that what ended up being almost two hundred hours of recording would eventually become a documentary.

Dumont-Gauthier: How did the MALBA exhibition come about?

Miraglia: It all began with an exhibition of Madalena Schwartz [a Hungarian-born photographer who lived in Brazil] that took place at the Moreira Salles Institute [in Brazil]. The curators of the show contacted me because they were aware that images of trans women and other individuals from the entertainment world who were once perceived as “sexually dissident” constituted an important part of the holdings of Foto Estudio Luisita. The curators wanted to paint a picture of what was happening in the region in the 1970s and ’80s, and so the work of the sisters was featured in the Argentine section of that exhibition, along with images from the Archive of Trans Memory.

The show was then scheduled to go to MALBA at the end of 2021, and I was approached by the museum to collaborate on Temporada Fulgor, a smaller exhibition that would create an interesting dialogue with the Schwartz show. Foto Estudio Luisita held a very faithful mirror to the popular Argentine imagery of the day, so working with this historical archive, but reassessing it from a contemporary perspective, was of great interest to the museum.

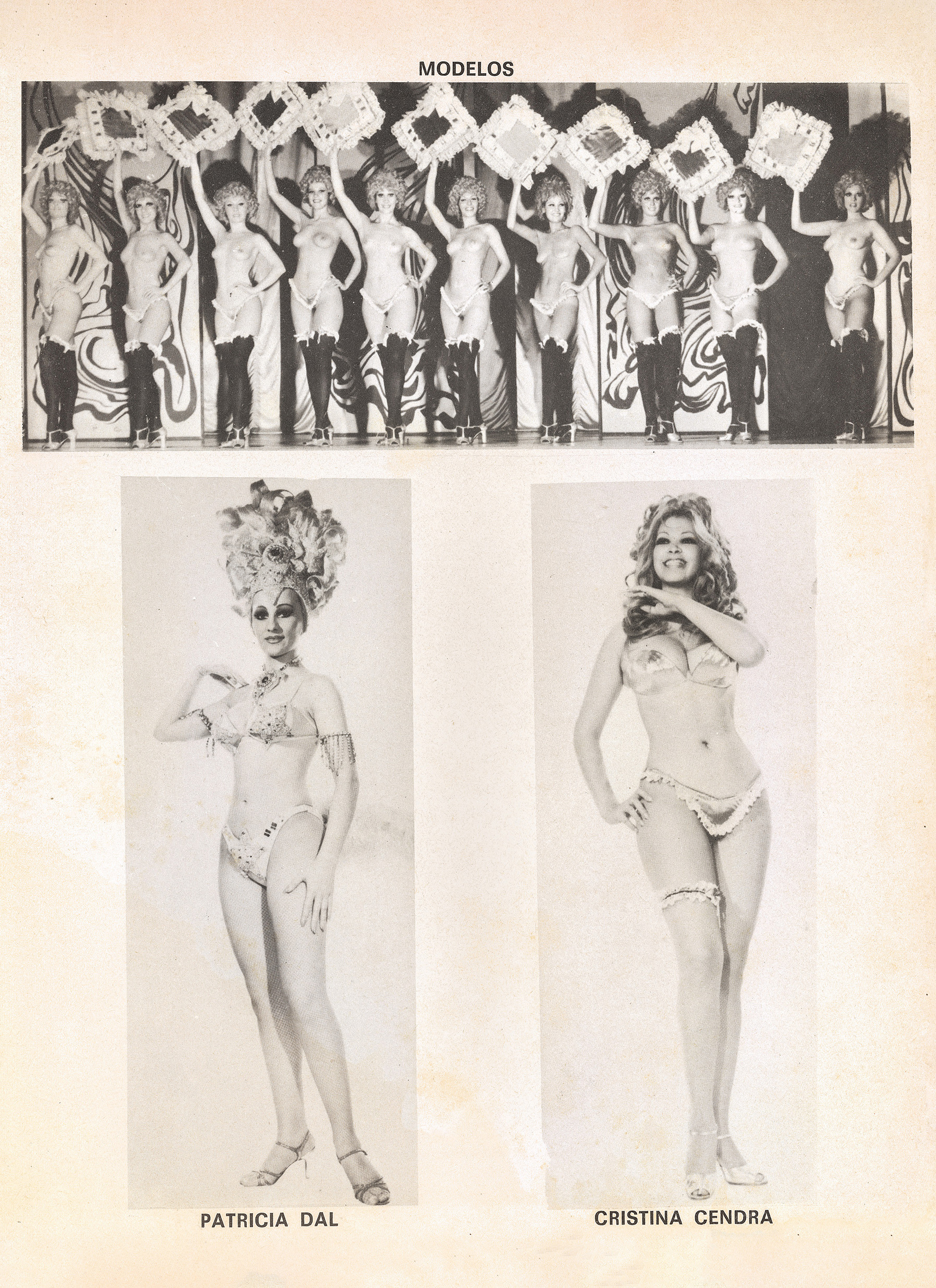

Sofía Dourron: Given the great diversity of material the archive contains, the museum wanted to build an exhibition whose focus would be on the studio’s involvement in revue. From there, we developed a project that would allow us to pose multiple questions. The goal was to reintroduce Foto Estudio Luisita to the public in such a way as to explain its legacy and contributions to photography—a feat that involved a reassessment of the canon of modern and contemporary photography, and of the boundaries between the artistic and the commercial, institutions and margins. It also required the creation of a proper gaze and language to communicate the sisters’ work dynamic, especially in regard to the home/studio aspect of their practice, and how it impacted their construction of images, of vedettes in particular. It was important to us to convey how the affective, intimate, and personal universe that defined their home/studio functioned. Lastly, we wanted to explore how we could link these things to the cultural phenomenon that was the Argentine theatrical revue and the larger social and cultural context in which the sisters evolved.

For this reason, the exhibition was divided into two spaces that were designed as an “outside”—public space, the theater, and the circulation of retouched images, ready for mass consumption in programs, magazines, and on marquees, as well as photographs passed from hand to hand—and an “inside”: a more intimate and warmer space that is nonetheless a workspace. Moving through these zones, the public could begin to understand the universe of the sisters, the theater scene of the day, and the cumulative affective force of these images, which are part of our collective imagination and our identities as Argentines to this day.

Dumont-Gauthier: One could say that they were at the right place at the right time, but what do you think led them to capture the makers of the golden age of revue the way they did?

Miraglia: In 1958, a year before Luisita and Eva came to join her in Buenos Aires, Chela worked as a photo retoucher. As luck would have it, their home/studio was in the entertainment center of the city, where all of the most popular theaters were located. The neighborhood was basically of runway of stars, performers, and artists! In the early years, before they could afford to equip the studio to their needs, they mainly made a living developing and making prints for tourists. In time, once they had acquired enough fabrics and lights and were able to turn their living room into a proper studio space, they were able to reach a wide audience.

The archive tells the story of an encounter between the matriarchal world of the Escarrias—one that is inhabited by female immigrants, canaries, and small dogs—and the macho world of revue.

Their real break came through Marfil, a friend and Colombian singer who lived next door. He introduced them to Cuban actress Amelita Vargas, who was already a household name in Argentina. They became fast friends, and in turn, she introduced them to [actress] Juanita Martínez and her husband, [actor and comedian] José “Pepe” Marrone, who were two of the most important figures in revue at the time. The sisters made great photomontages of the couple, and the successful reception of those images opened the doors of the famed Maipo Theater for them. The rest is history.

Dourron: There was a network that gave them access to the theater world. As immigrant women, they could relate and establish bonds with other immigrants, like their neighbor Marfil, who, as Sol mentions, started the chain of encounters that would grant the sisters a space within Buenos Aires’s revue world. The sisters’ presence in theaters such as Maipo was not a coincidence, but rather the result of great talent, professionalism, and a recognized career.

Dumont-Gauthier: How does their work fit into the photo scene of the time?

Miraglia: While there were many studios at the time, few were run by women or had female lab technicians. In the case of Luisa, Chela, and their mother, Eva—immigrant women of African descent from Columbia—not only was it a fully female-run studio, it was also a very matriarchal space. The women spent most of their time at home, working long hours. Though they played an important role in the entertainment business of the day, their participation was almost entirely remote. They didn’t partake in the city’s nightlife. They also never integrated into the photo scene of the day, which was primarily made up of European photographers who had immigrated to Argentina in the first half of the twentieth century.

Dourron: Because Luisita and Chela inherited a family trade, we can’t say that they were carriers of traditions, trends, or artistic movements outside of what they received from their parents. [Their father was a famous landscape photographer and their mother, an equally successful society portraitist.] Even when Luisita considered the photo schools in Buenos Aires, she felt there was little they could offer her. Her way of practicing photography, in Buenos Aires in particular, was also a form of living and surviving, a way to inhabit a world made up of all the people and objects that populated the space with them.

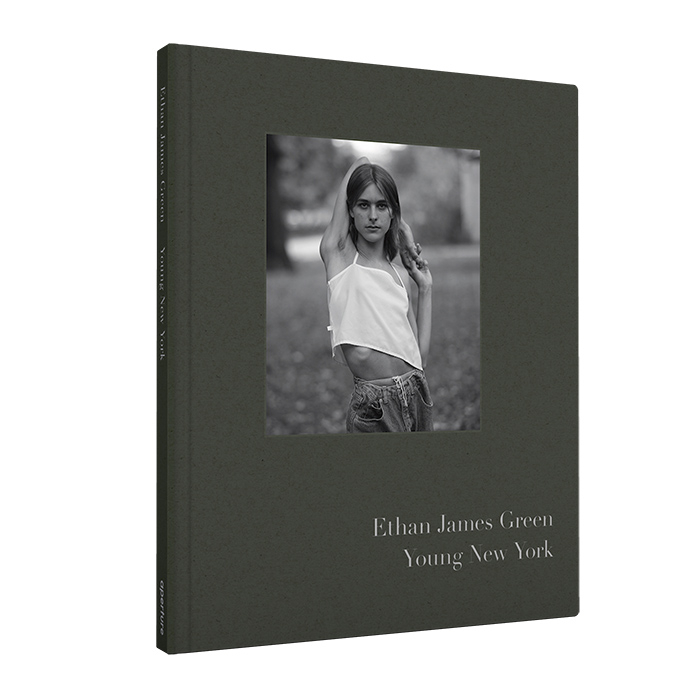

We can’t say that Foto Estudio Luisita participated in the photo scene of the day: the sisters remained on the margins, producing work only on demand, while building their own language and sensibilities within those parameters. I think we can think of them in a genealogy of female photographers who were part of a commercial circuit at the time, such as Annemarie Heinrich, who also photographed the Maipo stars for marquees and programs, or Olga Maza, another photographer whose legacy we have yet to explore and comprehend.

Dumont-Gauthier: The theme of perfection and the ideal body is prevalent in their photographic practice. In the exhibition, we saw images where the props were not erased and negatives revealing Chela’s incredible retouching work with red ink. Why was it important for you to display this?

Dourron: The diversity of the material and the untouched negatives, or as we call them, the “complete negatives,” convey a great complexity of meanings and sensibilities that are intertwined with one another. We’re not only talking about a desire to reach perfection; these images also display the tensions at play between the demands of the industry, cultural stereotypes, photographic canons, and a domestic language. In that way, they open the door for us to think about photography as something collective that is built within a particular space and under established material conditions, and as a link between the people, the space, and the objects that inhabit each image. In the case of the material that the sisters might not have considered appropriate for commercial purposes, we see different ways of embodying photography. The archive tells the story of an encounter between the matriarchal world of the Escarrias—one that is inhabited by female immigrants, canaries, and small dogs—and the macho world of revue. In turn, that encounter existed within a turbulent period of transformation in regard to the ways in which bodies, sexuality, and gender were being perceived.

Dumont-Gauthier: While there was a focus on achieving perfection—as Chela says in the documentary, “Everything had to be done perfectly or not done at all”—the sisters also captured a changing way of conceiving of and consuming bodies, making room for sexualities then considered “dissident.” The photographs reveal the complex realities surrounding body politics, especially for women and transgender people, in what was still a very conservative, heteronormative, and patriarchal society marked by repression and violence. How did the studio manage to claim this marginal space and thrive the way it did?

Dourron: Luisita and Chela were very warm and open people. No one was ever denied entry to the studio. Everyone who passed through their door was treated with the same respect, warmth, and affection, and photographed with the same passion, commitment, and professionalism. In that way, portraits of [actress and sex symbol] Moria Casán and [the pioneering transgender performer] Vanessa Show were made with the same care. The goal was the same for everyone: to “extract” all the beauty that the person being photographed had to offer.

The sisters did not discriminate based on gender, race, body, or sexuality, but I think that we have to remember that they operated within the revue world, which was a fairly complex phenomenon, especially during the dictatorship. It may sound surprising, but the military were regulars at the shows; they were admirers and even lovers of the vedettes, with whom they established bonds of all kinds. Someone who would have been oppressed in another public space—a trans woman or gay man, for example—was accepted within the context of the theater. On stage, these bodies could dance and delight the same military audience that would oppress them back in the streets: no longer protected by the boundaries of the theater, they had to go back into hiding and assume heterosexual norms in order to avoid anything from a beating to a night in jail, all the way to death.

I think we should also mention that the Escarria sisters did not conceive of their work through such a political gaze, nor were they trying to claim a space for themselves as public advocates for these individuals. They were doing their job in the best way they knew how—that is, in an affective, careful, and nonjudgmental way.

All photographs courtesy Foto Estudio Luisita

Dumont-Gauthier: While it was challenging for female photographers to make a name for themselves in the twentieth-century Argentine photo scene, some of the most important practitioners of that art were nonetheless women, including Grete Stern, Annemarie Heinrich, and Sara Facio. Along with them, the Escarria sisters captured a changing Argentine woman and society. Their archive and those of other female photographers contain stories and revolutions that are still unfolding to this day. What would you like the public to retain from the exhibition?

Dourron: Both the theatrical revue genre and the images that documented it belong to the field of the popular, and as such, they long eluded the cultural systems that have traditionally dominated both the fields of art and academia. Paradoxically, however, today these systems are actively looking for marginal archives and individuals, in an effort to bring back to light their languages and canons, which were hermetic for so long. The archive demonstrates the enormous contributions that revue and the sisters’ work made to our visual culture, to the formation of our collective identities, to the construction—and deconstruction—of our subjectivities and biases. From their humble beginnings in a world dominated by men, with silent force, they captured the stereotypes that Colombian and Argentine societies tried to impose on them. As they meticulously documented extraordinary scenes that they retouched to exhaustion, this duo, these image workers, continued to undo and deconstruct myths and mandates, including those of modern and contemporary photography.

Temporada Fulgor proposed a poetic and aesthetic exploration of images that for decades were only active within commercial circuits. The reassessment of the sisters’ body of work within the framework of contemporary artistic practices does not seek to erase or deny its popular essence, nor to paralyze it as a nostalgic fetish. Rather, the archive appeals to the renewal of a sensibility that is charged with meaning and anchored in the universe of work and production, in the exuberance and excess of the night, and in domestic tenderness. The archive contains a small revolution: the work of women who, through their daily actions, broke with the patriarchal mandates of their time.

Interview translated from the Spanish by Marina Dumont-Gauthier.