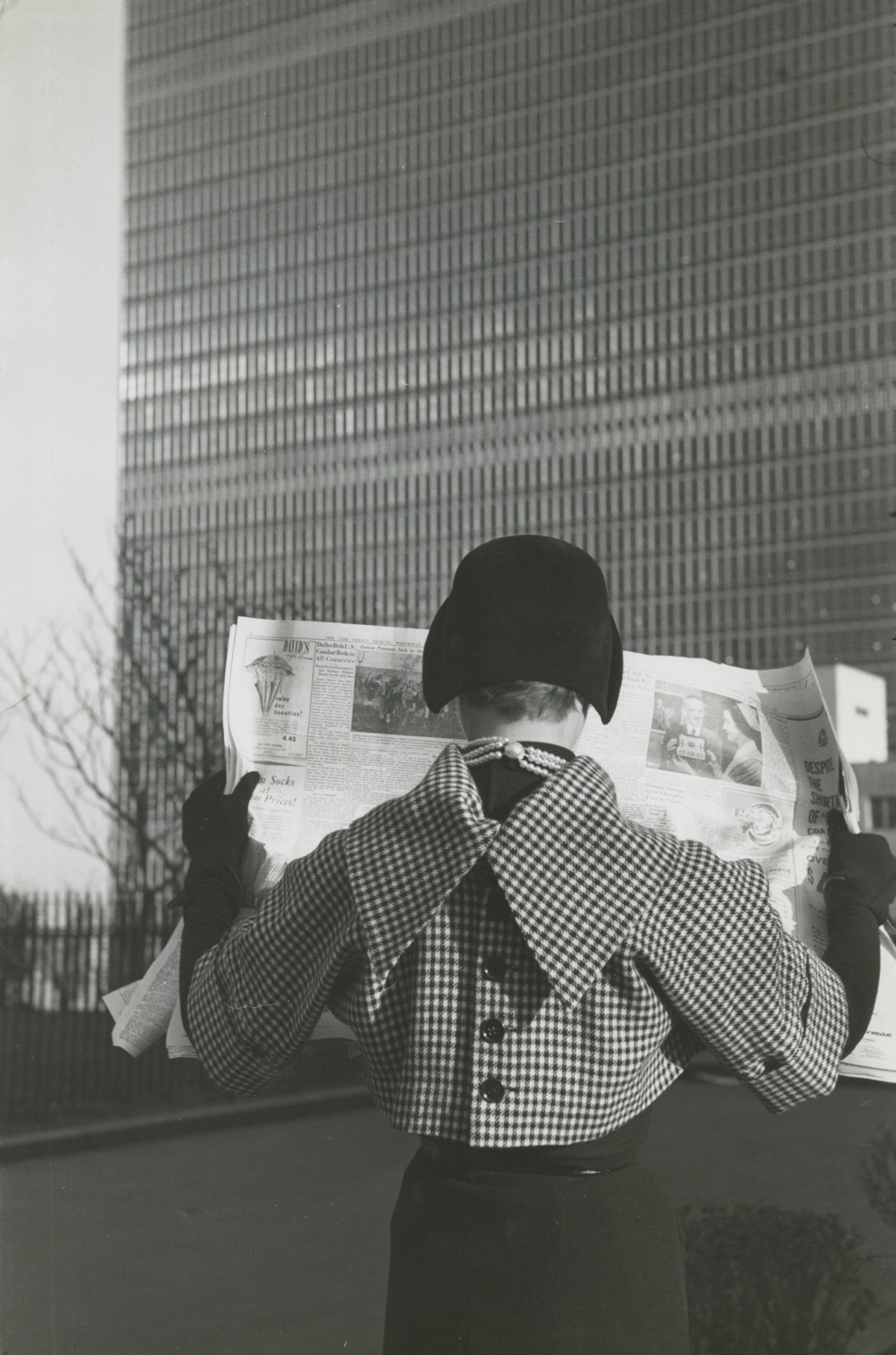

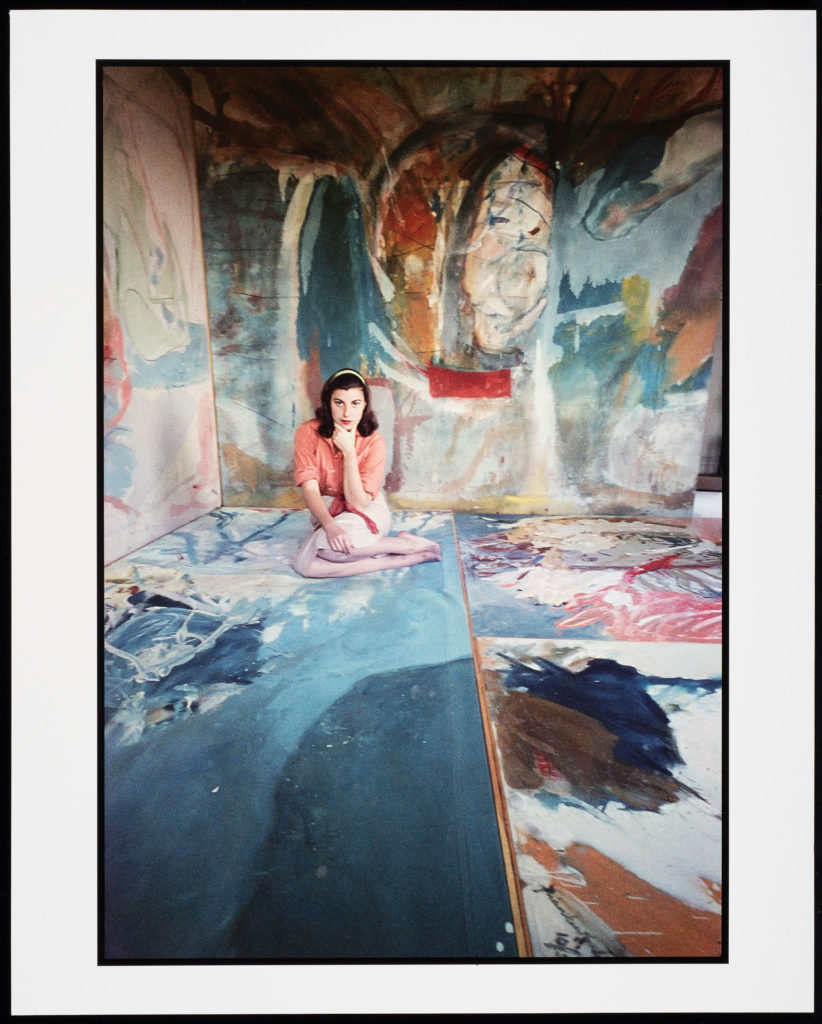

Frances McLaughlin-Gill, Nan Martin, Street Scene, First Avenue, 1949

© Estate of Frances McLaughlin-Gill

Since it’s concerned, above all, with context and the printed page, Modern Look: Photography and the American Magazine at the Jewish Museum in New York is an exhibition as much about graphic design as it is about photography. From its opening galleries, it focuses on the influence these ways of seeing exerted on one another beginning in the 1930s, when photography began replacing illustration in magazines. The creative push and pull that resulted was exciting, bringing out the best on both sides; Modern Look tracks that synthesis over the next two decades, focusing on key players both on and off the page.

Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York

In a period when art became increasingly linked with activism, many of its innovators were recent European exiles, fleeing repression and a widening war, including Herbert Bayer, Erwin Blumenfeld, Josef Breitenbach, György Kepes, Herbert Matter, László Moholy-Nagy, and Martin Munkácsi. Kepes, quoted in the Modern Look catalogue, spoke for the group’s most high-minded impulses in 1944, when he suggested that art and design can be functional as well as expressive: “Posters on the streets, picture magazines, picture books, container labels, window displays . . . could disseminate socially useful messages, and they could train the eye, and thus the mind, with the necessary discipline of seeing beyond the surface of visible things, to recognize values necessary for an integrated life.” Whether any of these artists realized the most principled of these goals is debatable, but “train the eye” they collectively and most effectively did.

Because they were in a position to employ and direct so many of their peers, the most influential of the émigrés were the artists and art directors Alexey Brodovitch, who took over the design of Harper’s Bazaar in 1934; and Alexander Liberman, whose life-long career at Vogue began in 1943. Both were brilliant, sophisticated, imperious, and famously volatile, alternately charming and waspish; both helped define the “modern look” as designers, assigners, and mentors.

Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York

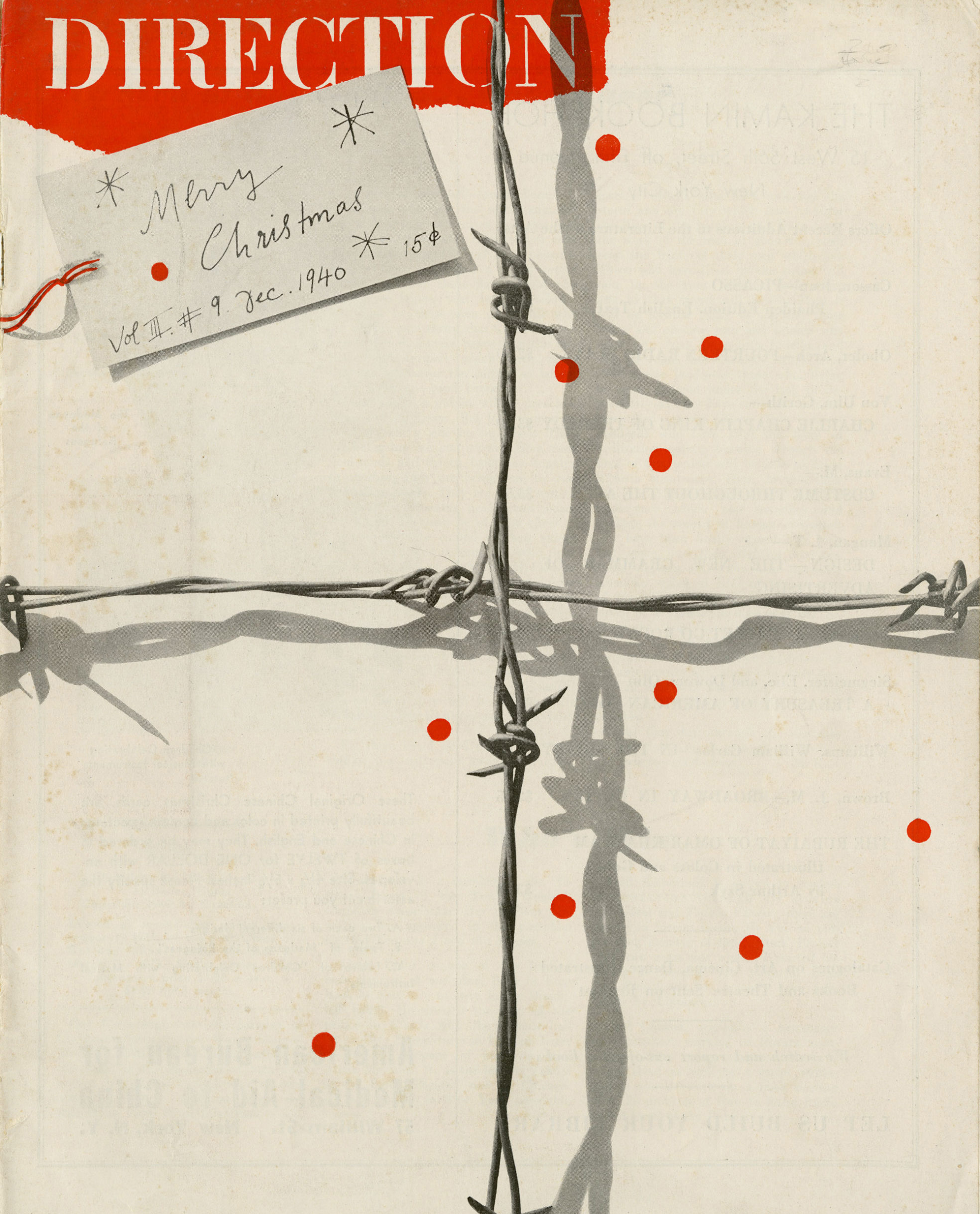

The Jewish Museum exhibition’s curator, Mason Klein, introduces Brodovitch in one of the first galleries with the elegant cover, hallucinatory spreads, and a page-by-page digital presentation of Brodovitch’s 1945 book Ballet, an impressionist vision of the Ballets Russes in performance. Before coming to New York, Brodovitch had painted sets for Sergei Diaghilev’s original Ballets Russes in Paris; and once in New York, he adopted the impresario’s most quoted directive, “Étonnez-moi! (astonish me)” as his own. Brodovitch’s work in the show, including spreads from Observations (1959), the book that introduced Richard Avedon to the larger world, astonishes us. He might be given showstopping star treatment, but Brodovitch always shares gallery space with other graphic geniuses—including Bayer, Matter, and Paul Rand—who rivaled him at witty and arresting design.

As for Liberman, although he is represented in the exhibition by reproductions of seven knockout covers he conceived for Blumenfeld at Vogue from 1944 to 1954, the extraordinary still-life and portrait images he commissioned from Irving Penn are shown out of context, leaving the art director’s role vague or unacknowledged.

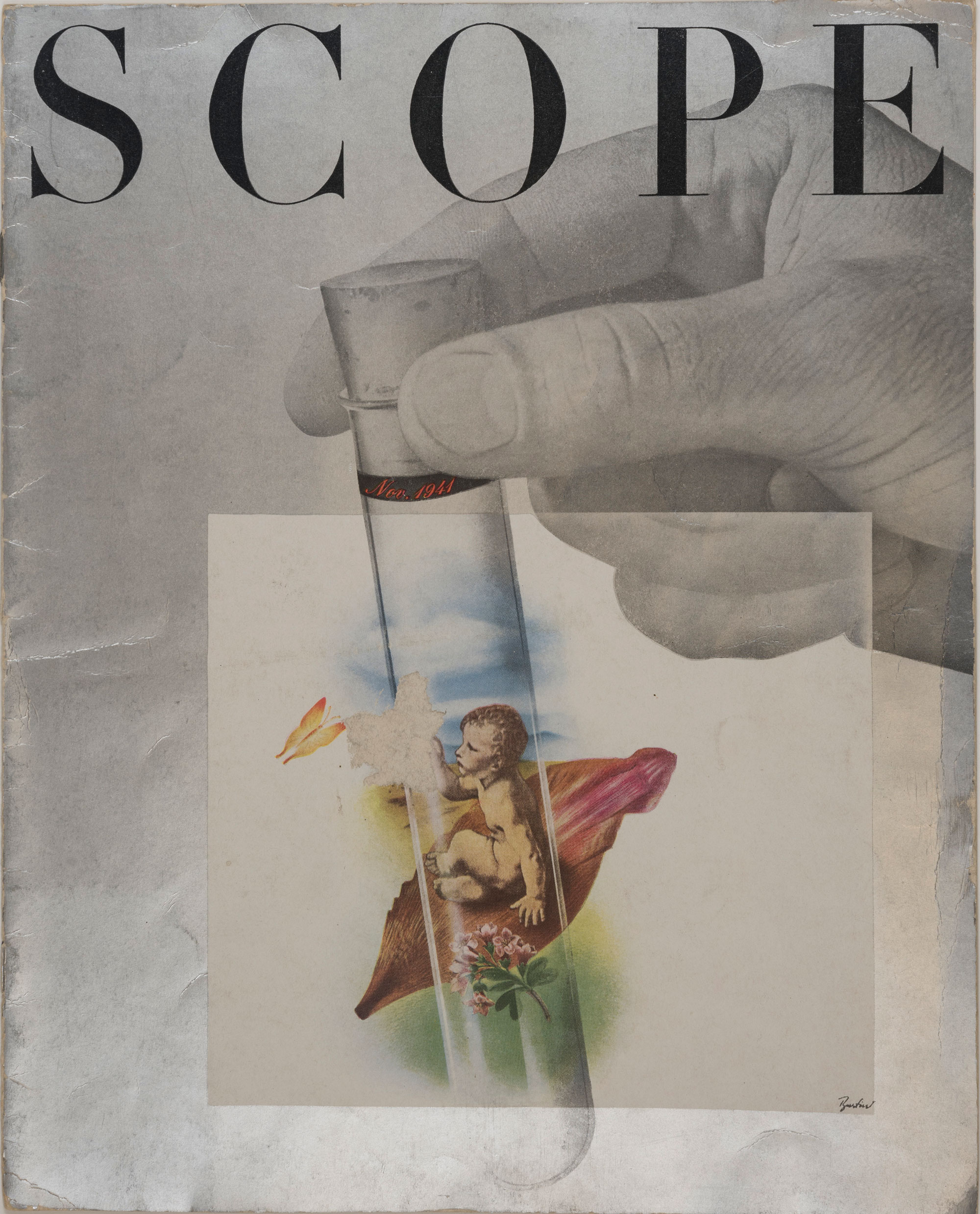

Cary Graphic Arts Collection, Rochester Institute of Technology

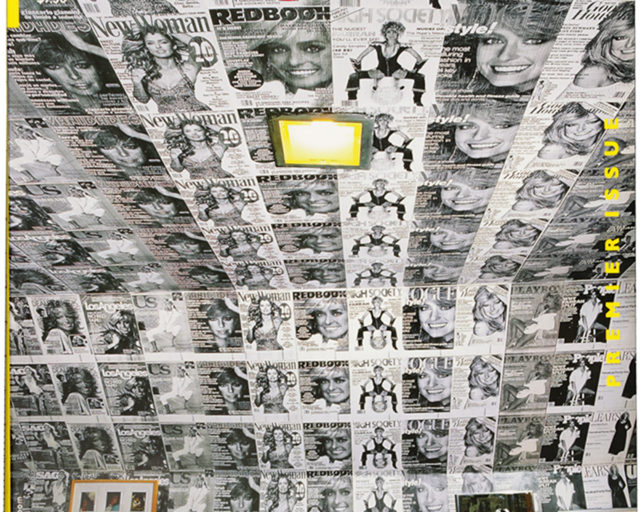

If the attention to these two magazine design legends is predictable, Klein goes to some lengths to overturn expectations elsewhere in his show, primarily by focusing on women photographers: Lillian Bassman, Margaret Bourke-White, Louise Dahl-Wolfe, Frances McLaughlin-Gill, and Lisette Model. Bourke-White and Model help to open up the show, moving further beyond fashion to include the magazines Life, Fortune, and Flair, and surprisingly inventive industrial titles like Scope and Westvaco Inspirations for Printers. Gordon Parks, one of the very few Black photographers with a substantial career in magazine work at the time, is a lonely outlier here, joined only by Roy DeCarava, with a single, superb photograph of jazz musicians, but supported in spirit by two galleries of atmospheric black-and-white images that close the exhibition on a moody, contemplative note.

© The Gordon Parks Foundation

Setting Parks’s photographs alongside works by Louis Faurer, Robert Frank, William Klein, and Saul Leiter—nearly all of it made on the streets of New York—seems intended to remind viewers of socially engaged Photo Leaguers like Model, Sid Grossman, and Walter Rosenblum, seen in these same galleries in 2011’s The Radical Camera: New York’s Photo League, 1936–1951 (also curated by Klein, with Catherine Evans). The league’s activities may not have been covered by many of the magazines featured here, but its soulful, reportorial style impacted and inspired most of the photographers; and the powerful last passage of Modern Look makes that abundantly clear.

© Estate of Lillian Bassman

Liberman is quoted in the catalogue insisting he wanted to inject “the grit of life into this artificial world” at Vogue. Without making a similar claim, Brodovitch frequently did exactly that at Harper’s Bazaar, and many of the other magazines here (even Fortune at its 1940s best) made grit a specialty. Given the state of the world—with a post-Depression boom quickly swept up in a sobering but invigorating war, followed by an even more aggressive boom—how could they not? Without losing sight of elegance, inventiveness, and style as a saving grace, Klein grounds his show in seriousness, if not grit. But along the way, his focus on the magazine nearly evaporates. Many of the photographs did not appear on the printed page, and those that did are rarely seen in context. The American magazine remains as a force field and an incubator, but its absence in Modern Look as an object of size, weight, and graphic impact is puzzling and disappointing.

Modern Look: Photography and the American Magazine is on view at the Jewish Museum, New York, through July 11, 2021.