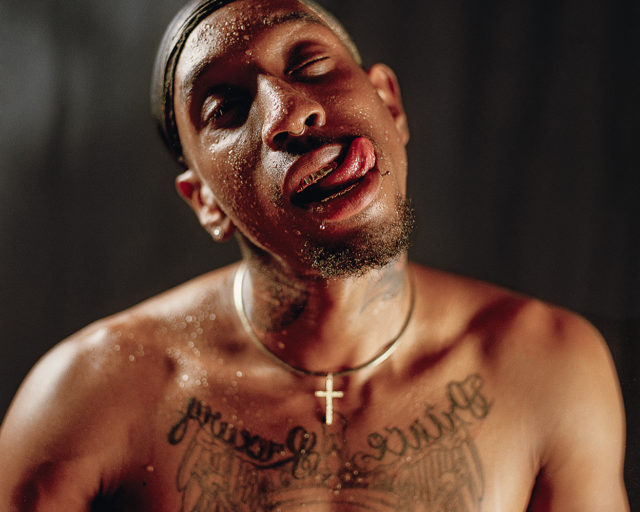

Ayana V. Jackson, Sea Lion, 2019, from the series Take Me to the Water

Courtesy Mariane Ibrahim Gallery, Chicago

In May 1803, a slave ship bound for St. Simons Island, off the coast of Georgia, neared its final destination. On board were seventy-five captives belonging to the Igbo peoples of West Africa. As the ship approached the island, the Igbo rose up in revolt, forcing the white crew to jump overboard, running the vessel aground. On land, according to a contemporary account, the Igbos “took to the swamp.” Rather than risk being returned to captivity, they lined up hand in hand and walked into the water where many of them drowned.

Variations on the story of the Africans who found liberation through suicide have been told over successive generations across the Atlantic world, from the United States to South America and the Caribbean. In the process, the tale has taken on the resonant power of myth. Some versions have the Igbos returning to Africa by walking on the waves or along the seabed. Others describe them taking to the sky and soaring back to their homeland. Echoes of the story can also be heard in popular culture. It is the base material for Toni Morrison’s novel Song of Solomon and Julie Dash’s film Daughters of the Dust. Beyoncé references it in a scene in her Lemonade film. And in Black Panther, Michael B. Jordan’s character, Erik Killmonger, alludes to the tale with his dying words: “Bury me in the ocean with my ancestors who jumped from ships, ’cause they knew death was better than bondage.”

Courtesy the artist

Real-life events turned folklore, such as the story of the Igbo slaves, along with myths, legends, and spiritual beliefs drawn more widely from the history and culture of the African diaspora, have increasingly become a powerful source of inspiration for Black artists and creative figures. A trio of recent photographic projects illustrates renewed attention to these stories.

Ayana V. Jackson’s series Take Me to the Water (2019) is inspired by mythological African water deities such as Mami Wata and Olokun, spirits venerated in Africa and the diaspora for their power to heal and liberate those who summon them. In addition to African legends, Jackson’s project draws on the fable of a Black Atlantis created by Drexciya, the enigmatic 1990s Detroit techno duo. In the group’s telling of it, Drexciya is also the name of a colony located on the floor of the Atlantic Ocean populated by the descendants of pregnant African women thrown overboard from slave ships. The women’s fetuses learned to breathe through the embryonic fluid of their mothers’ wombs and were born able to live underwater. In Jackson’s pictures, the Drexciyans craft their clothes from human detritus: a bodice of spoons, a skirt of flip-flops, a veil of black netting. But they are defiant, noble creatures, glorious proof of how Black life might have flourished without the depredations of the slave trade.

Similarly, the artist Adama Delphine Fawundu merges myth, memory, and spiritual belief in her photography-based multimedia project Sacred Star of Isis (2017–ongoing). Fawundu’s family origins lie in Sierra Leone, and in the series, she invokes the presence of West African deities such as Mami Wata while photographing herself in Argentina, upstate New York, and other locations where her forebears were scattered by slavery. These works suggest the possibility of new narratives and networks that can be formed from traditional myths and beliefs despite the efforts of the slave trade to sunder Africans from the heritage of their homelands.

Courtesy Mariane Ibrahim Gallery, Chicago

Lina Iris Viktor draws from African cosmologies as well as Aboriginal dream paintings and other sources of Indigenous and non-Western myths and beliefs in her art. Viktor was raised in London by Liberian parents who were forced to flee the country amid civil war in the 1980s. The dazzling, gold-embossed pictures of her series A Haven. A Hell. A Dream Deferred (2018) offer a mythological history of the country, conjuring Liberia as an uneasy utopia, both a paradise lost and a cautionary tale about the pathology of colonization.

In their shared tendency to blend historical fact and lyrical folklore, and to juxtapose the spiritual, the supernatural, and science fiction, we might usefully group the art of Jackson, Fawundu, and Viktor under the heading of the “Black fantastic,” works of speculative fiction that draw from history and myth to conjure new visions of African diasporic culture and identity. The scholar Rosemary Jackson describes the “fantastic” as a form that reaches beyond the boundaries of realism and dispenses with “rigid distinctions between animate and inanimate objects, self and other, life and death.” The fantastic, she writes, “has to do with inverting elements of this world, re-combining its constitutive features in new relations to produce something strange, unfamiliar, and apparently ‘new,’ absolutely ‘other’ and different.”

The Black fantastic shares terrain with genres such as Afrofuturism and Afrosurrealism, artistic realms with their own expansive takes on Black experience. But to my mind, the Black fantastic is less a movement or a rigid category than a way of seeing shared by artists who grapple with the legacy of slavery and the inequities of racialized contemporary society by conjuring new narratives of Black possibility. The roots of the Black fantastic emerge from pioneering authors, musicians, and filmmakers of the 1960s and ’70s such as Octavia E. Butler, Henry Dumas, Amos Tutuola, Sun Ra, and Ousmane Sembène. But a raft of prodigiously talented contemporary practitioners is now taking the lead, among them the artist Wangechi Mutu, the novelist N. K. Jemisin, and musicians such as Solange and Kamasi Washington.

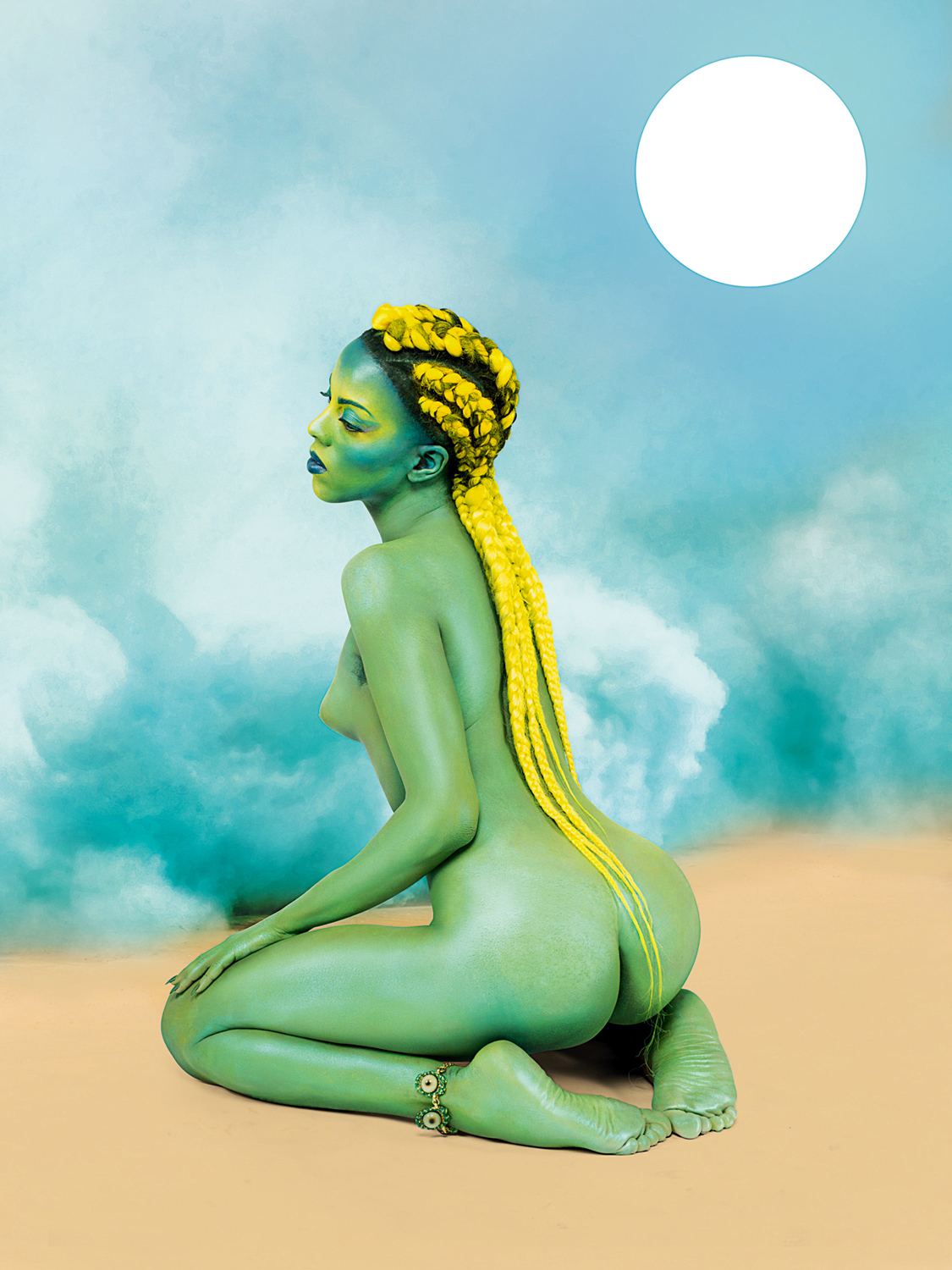

Courtesy the artist and Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, and Art Resource, New York

This perspective stretches from, say, the enigmatic tableaux of the South African artist Mohau Modisakeng, whose Land of Zanj images (2019) are rich with historical allusion, to the explorations of race, gender, and queer sexuality conducted by the likes of Rotimi Fani-Kayode, Mickalene Thomas with her 2019 Orlando series made for this magazine, and Juliana Huxtable with her 2013 Nuwaubian Nation photographs. In those latter images, Huxtable inserts herself into digitally rendered landscapes inspired by the Nuwaubian Nation, an African American religious sect whose credo borrows from Islam, ancient Egypt, and stories of alien visits to Earth. Huxtable, who describes the portraits as “self-imaginings,” depicts herself as an otherworldly, green-skinned being, a figure whose very form critiques existing social norms and categorical distinctions while gesturing to alternate, more mutable states of identity.

But why are so many figures being drawn to art that ostensibly seeks to escape from, rather than contend with, the long history of anti-Black racism in the West, especially in the era of Black Lives Matter and the international protests triggered by the killing of George Floyd?

The success of Marvel movies and television shows including Stranger Things and Game of Thrones, to name just two, makes clear that fantasy is a dominant cultural language of our times. One of the unanticipated consequences of the superhero and sci-fi boom is that it has given space for Black artists to explore Black life in ways that are more allusive and audacious than hitherto possible. For example, the dazed and sardonic tone characteristic of recent shows and movies such as Us, Atlanta, Get Out, and Sorry to Bother You can surely be taken as a response to the horror and absurdity of a world in which Black people can be harassed, arrested, or killed while going bird-watching, cycling, jogging, or lying asleep in bed at night.

Courtesy the artist and Jessica Silverman Gallery

Fundamental to the Black fantastic is a skepticism about the claim that modern liberal democracies are built on ideals of tolerance, rationality, and equality. Those values feel profoundly flawed in their application when you consider how the wealth and advancement of the West were built on four hundred years of the slave trade, and how the intellectually and morally corrupt arguments of racial hierarchy used to justify slavery still poison our societies today. Artists working from the perspective of the Black fantastic are intent on both critiquing Western notions of progress and, in riposte, offering counterimages of Black imaginative reach.

The British Guyanese artist Hew Locke has had a long fascination with the role that public monuments play in the formation of Western cultural identity. For the past two decades, he has been photographing statues of prominent historical figures from Queen Victoria to Edward Colston, the slave trader whose bronze effigy was recently toppled by Black Lives Matter protesters in Bristol. Locke then embellishes the pictures with objects, creating elaborate fetish figures whose often-problematic relationships to race and empire are now made visible. For his 2018 New York–based iteration of this project, he reworked the statues of public figures such as George Washington, Peter Stuyvesant, and J. Marion Sims. Each of the men he selected benefited from slavery or the exploitation of people of color, and in covering them with totems and tchotchkes, Locke reveals what their power was built on. An illustration by William Blake of a slave being tortured dangles from the forearm of Washington, a reminder that the United States’ first president owned over one hundred souls.

© the artist and courtesy Galleria Fonti, Naples

By contrast to such brutal and dispiriting histories, some of the still photographs from Isaac Julien’s 2005 film installation Fantôme Créole depict a legacy of cultural renewal in late twentieth-century Africa. In the 1960s and ’70s, nation after nation in Africa secured independence from colonial rule. The optimism of liberation triggered a creative flourishing across the arts of Africa and the diaspora, from the novels of Chinua Achebe and the photography of Malick Sidibé to the films of Ousmane Sembène and Med Hondo. Julien’s images capture some of the thrilling, futuristic structures inspired by that period. Built in the 1980s, the Place des Cinéastes, in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, for example, a towering monument of shapes representing stacks of film reels, telephoto lenses, and other camera equipment, is an homage to the country’s independence- era role as the heart of filmmaking in Africa. Julien confines his study to Burkina Faso, but across the continent, you can find buildings of similarly audacious design. Ghana’s flying saucer–like International Trade Fair Centre, in Accra, and the extraordinary La Pyramide commercial center in Abidjan, Ivory Coast, speak to a shared desire to break free of European aesthetic strictures in favor of an exhilarating architecture of freedom and the fantastic.

Visionary architecture also plays a key role in the Angolan artist Kiluanji Kia Henda’s Icarus 13 series from 2007. The project purports to document Angola’s first space mission, complete with images of a spectacular rocket launch from mission control in Luanda. The photographs are imaginary, courtesy of the artist, who creates what have been described as “pliable fictions.” But the settings are real. A dome-shaped cinema from the independence period doubles as an astronomical observatory, while the towering mausoleum for Angola’s former leader Agostinho Neto becomes a sleek rocket headed to the stars.

With works such as Julien’s and Kia Henda’s in mind, we can think of the Black fantastic as a project of liberation. For much of the history of Western thought, the peoples of the African diaspora have functioned as a synonym for the primitive and perpetually underdeveloped. Writing in the nineteenth century, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel dismissed the continent as “enveloped in the dark mantle of Night,” its people only representative of “natural man in his completely wild and untamed state.” Even today to talk of Africa, or the culture, myths, and beliefs that have spread from there across the Atlantic world, is to invoke the antithesis of Western modernity. In collapsing distinctions between fact and fiction, science and the supernatural, the Black fantastic also dissolves the false connection between Blackness and backwardness. Instead, it makes clear that belonging to the African diaspora means being a participant in a shared endeavor of artistic imagining and world making that stretches back hundreds of years into the past and reaches always into the future.

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 241, “Utopia,” under the title “The Black Fantastic.”