The Photographers Who Captured Love and Longing

An exhibition at the International Center of Photography offers an expansive take on how images can be used to create, sustain, and destroy intimacy.

René Groebli, from The Eye of Love, 1952

Courtesy Galerie Esther Woerdehoff

The logical way into Love Songs: Photography and Intimacy, at the International Center of Photography (ICP) in New York, is to turn right at the doors from the building’s dramatic stairwell (left from the elevator) and wind your way counterclockwise through the space. Thematically, the exhibition moves around Nan Goldin’s The Ballad of Sexual Dependency (1973–86) and the pairing of Nobuyoshi Araki’s Sentimental Journey (1971) and Winter Journey (1989–90), which are judiciously placed at even intervals within the sequence of works by twelve artists on ICP’s second floor (an additional four bodies of work are arranged on the third). Turn the other way, however, and you’ll find yourself in the middle of the messy set of relationships that constitute the setup of Leigh Ledare’s incredible Double Bind (2010).

Courtesy the artist

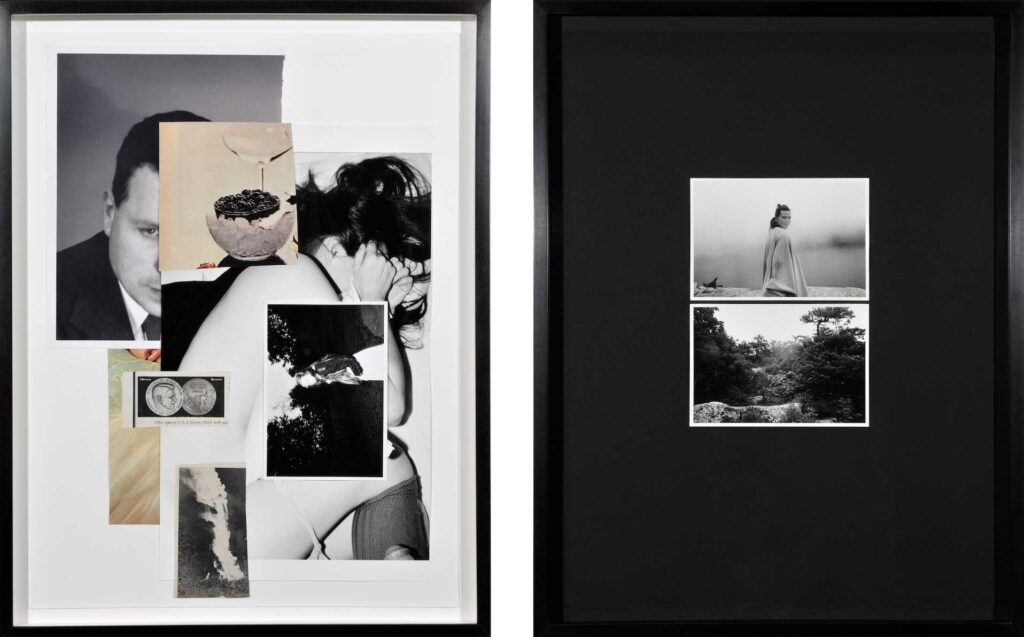

Five years after Ledare and his wife Meghan divorced, he asked her to accompany him to a remote cabin in upstate New York, where he wanted to photograph her over the course of four days. Meghan agreed, but in the time between Ledare’s invitation and their departure, she remarried. To complicate things further, her new husband is also a photographer, Adam Fedderly. Still, Ledare and Meghan stuck to their itinerary. They traveled together but slept in separate beds. Ledare took five hundred pictures of Meghan smiling, glowering, strutting through morning shadows and wildflowers. Then he arranged for Meghan and Fedderly to repeat the trip two months later, going to the same cabin for the same duration and taking the same number of pictures, returning them to Ledare as unprocessed rolls of film.

Double Bind takes shape as a room-size installation. The images by Ledare are placed on black backgrounds; the images by Fedderly are placed on white backgrounds. Smaller prints are stacked in a glass vitrine. The installation features beguiling collages, another vitrine filled with pictures cut from magazines, and a framed piece of paper on which the artist has scrawled the “conceptual script” of the piece. Does Meghan Ledare-Fedderly appear happier, more hopeful, more seductive in one set of images? Is she angry, resentful, rueful in the other? Where does her love run deepest? The genius of Ledare’s installation is that he scrambles expectations and gives no easy answers. Intimacy is, above all, complicated.

Courtesy the artists

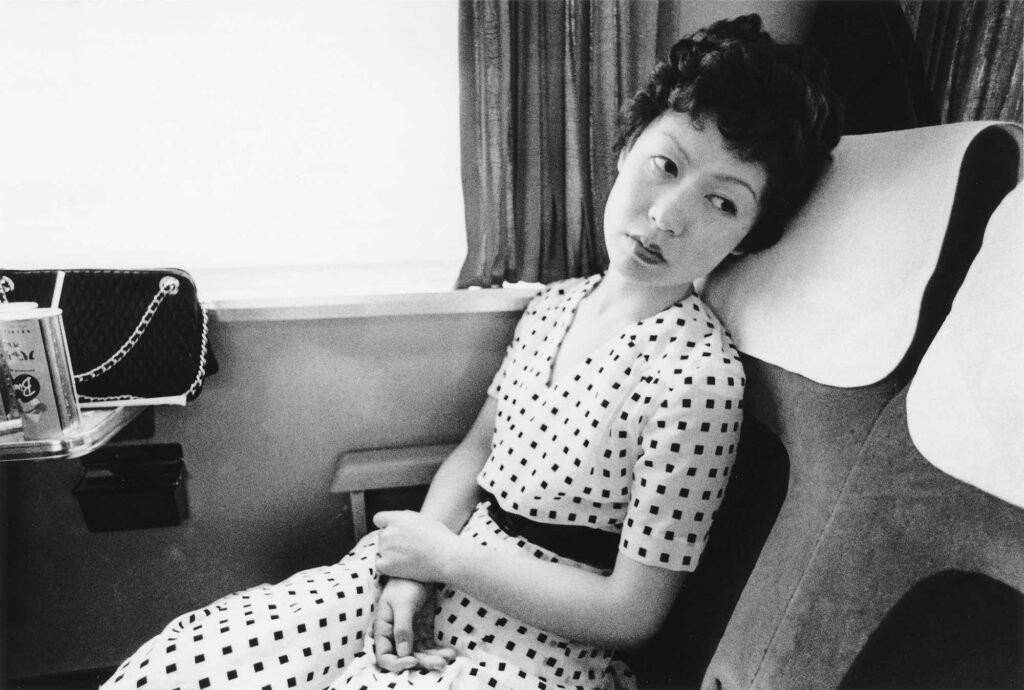

Love Songs has arrived at ICP from Paris, where it was originally organized by Simon Baker and exhibited last summer at the Maison Européenne de la Photographie (MEP) under the title Love Songs: Photographies de l’intime. Goldin’s Ballad, presented here as a series of nine prints rather than a slideshow, as originally shown, captures a wholly interior world thick with lust, loss, and longing. Atmospheric and diaristic, Goldin’s images are as much about the intensity of friendships as a bulwark against trauma as they are about sex or drugs. By contrast, the two series by Araki delve into the photographer’s marriage to Yoko Aoki—from their wedding and honeymoon in 1971 to her illness and death in 1990—and follow a narrative line that is tender, episodic, and tragic, with none (or little) of the abjection and domination that make much of Araki’s other work so dubious today.

Courtesy Taka Ishii Gallery

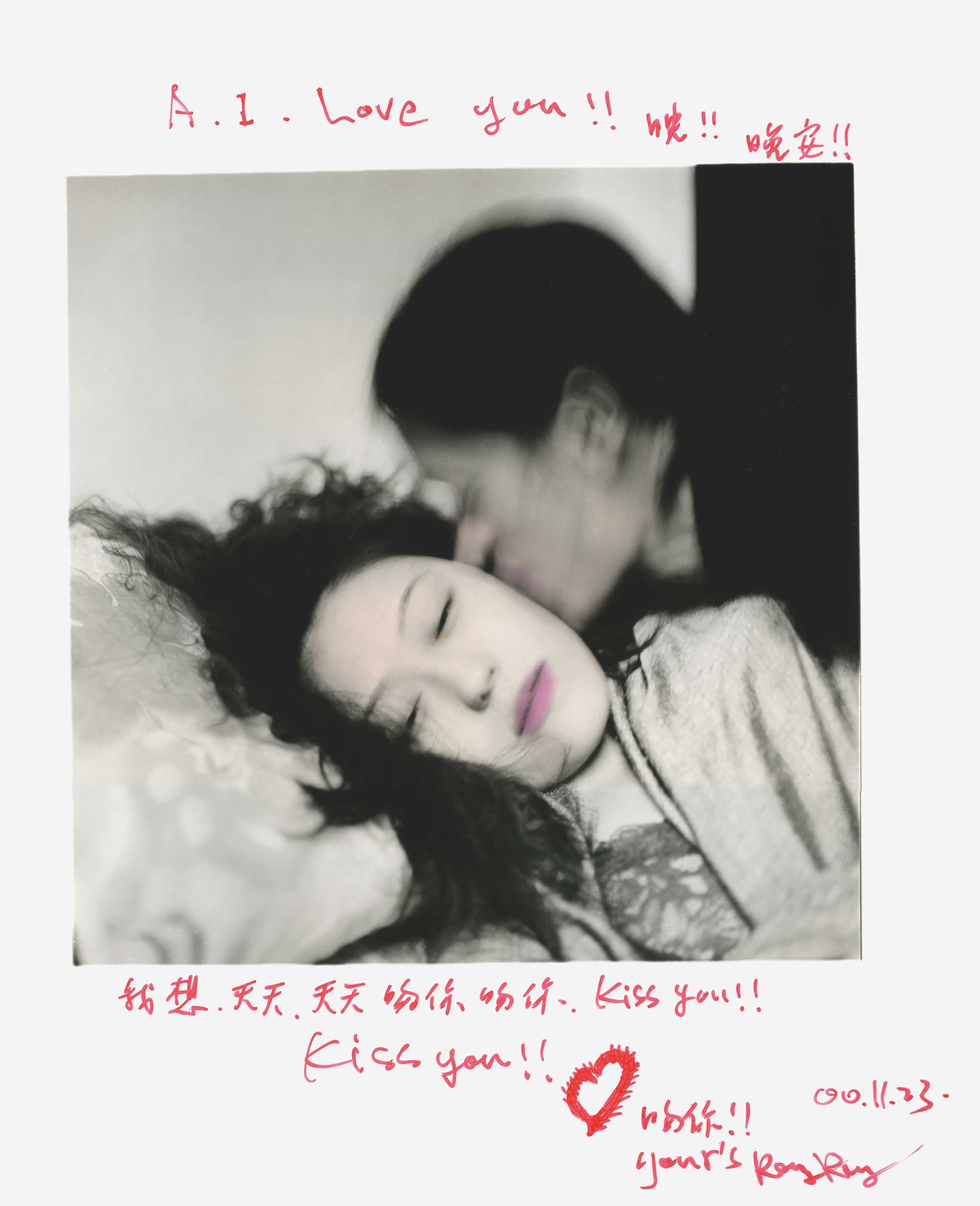

The series by Goldin and Araki are landmarks in the late twentieth-century history of photography. With an emotional rawness that was unprecedented in their day, they turn the outward gaze of traditional documentary photography inside out. Their influence reverberates throughout the New York iteration of Love Songs, particularly in projects such as Fouad Elkoury’s On War and Love (2006), a literal diary about a relationship falling apart against a backdrop of Beirut being bombed and besieged; Ergin Çavuşoğlu’s Silent Glide (2008), a highly scripted three-screen video installation about lovers calling it quits amid the industrial devastation of an old Ottoman town east of Istanbul; Collier Schorr’s extended rumination on gendered looking, titled Angel Z (2020–21); and the delicate structure of annotation and exchange defining RongRong & inri’s Personal Letters (2000).

Courtesy the artist and Rachel Uffner Gallery

Love Songs has undergone a radical transformation in the move to New York. The ICP iteration, organized by the perspicacious and resourceful independent curator Sara Raza, has dispensed with the works of Emmet Gowin, Hideka Tonomura, and Larry Clark, whose grittiness is excessive in combination with Goldin and Araki. Gone, too, is the pretense of using intimacy to reconfigure the history of photography. Instead, Love Songs offers a subtler, more expansive take on how photography can be used to create, sustain, and destroy intimacy in its many forms.

Love isn’t synonymous with intimacy. Each can exist without the other, and intimacy is just as often fraught, messy, and conflicted.

Raza’s additions are stellar. Of the sixteen artists who span seven decades and three continents, five are completely new to the show. Raza splices old and new together. The flirtatiousness of René Groebli’s high-contrast black-and-white photographs of his wife on their Parisian honeymoon creates a fascinating dialogue with the blended-family chaos in Motoyuki Daifu’s Lovesody (2008), chronicling the photographer’s infatuation with a single mother about to give birth to her second child, and the explosion of laundry, dishes, trash, breast milk, and snot that follows.

© the artist

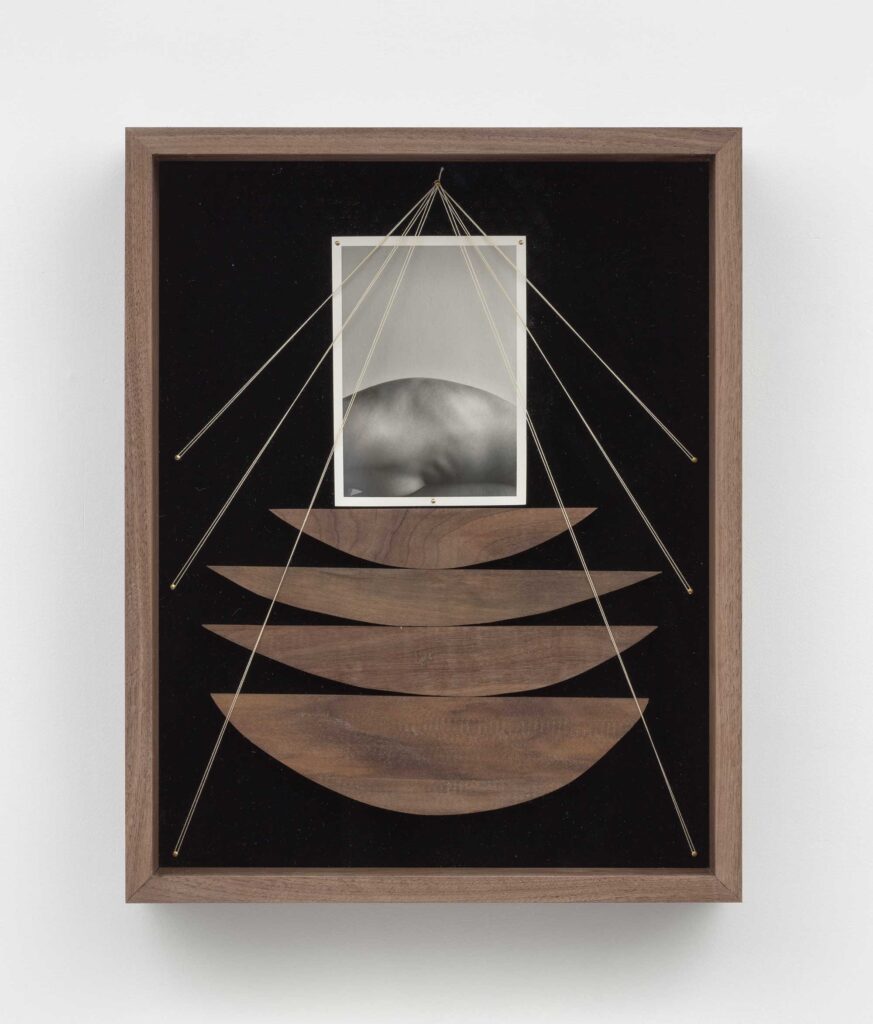

Karla Hiraldo Voleau’s immersive account of her discovery of a lover’s double lives and infidelities (Another Love Story, 2022) is expertly installed, replete with a maze of hanging ribbons and flowers, and utterly engrossing. Sheree Hovsepian’s mesmeric constructions made from ceramics, nails, string, photograms, and wood combined with images of her sister’s body add a necessary element of abstraction to the show.

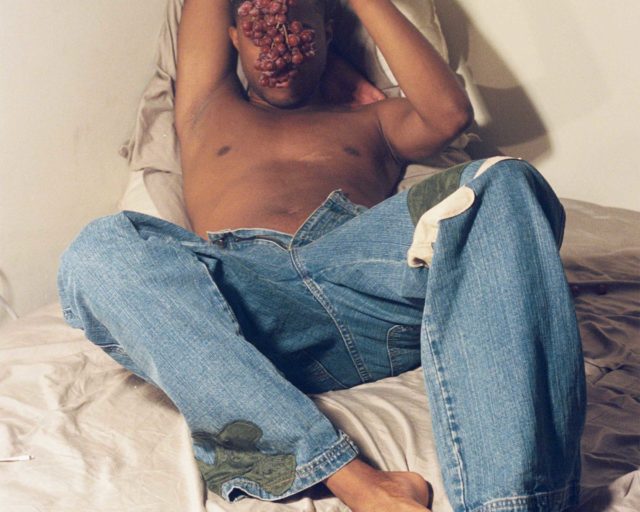

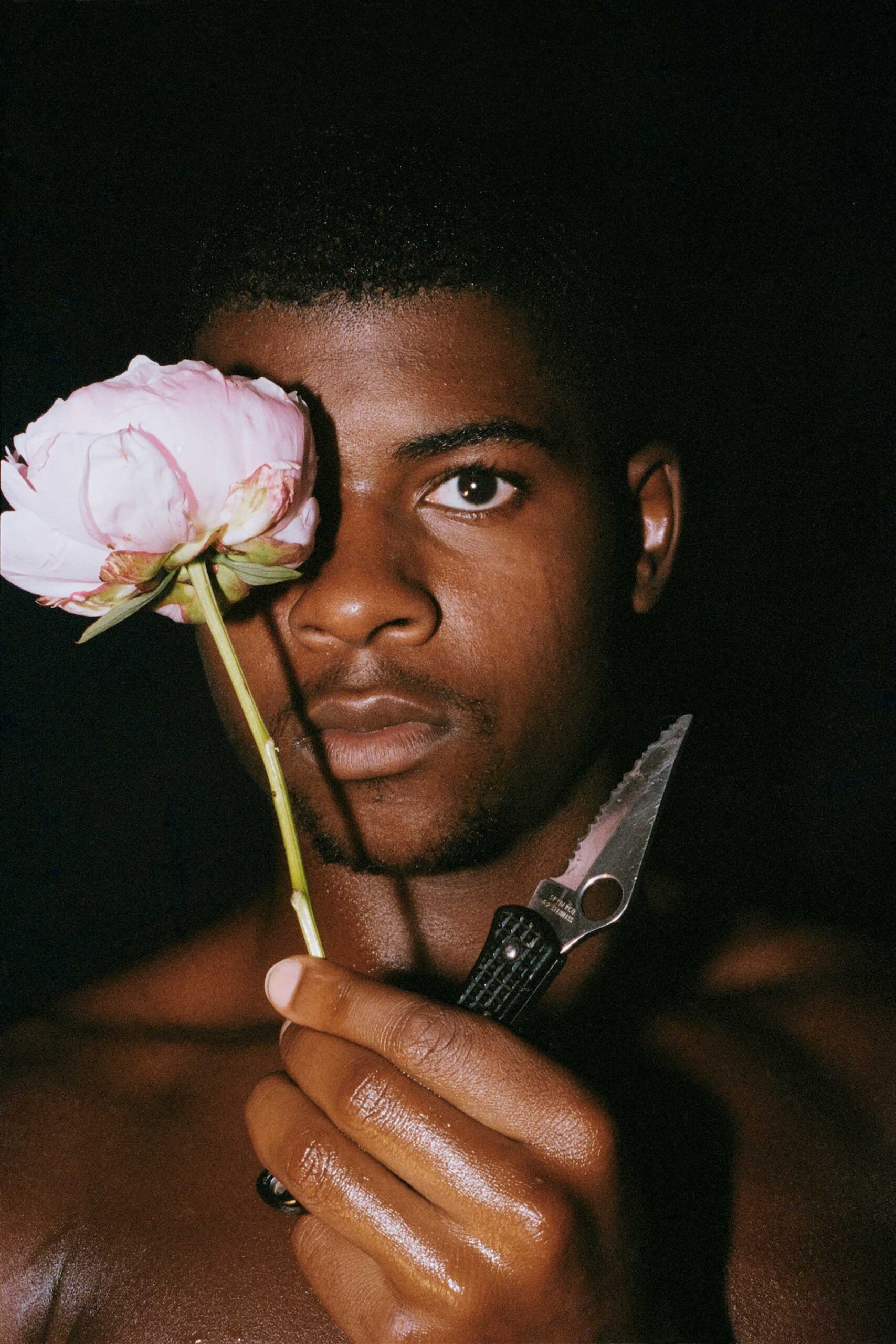

The real highlight of the exhibition, however, is the lush and dramatic portraiture of Clifford Prince King, whose work is featured on the cover of the catalog and best embodies the idea of intimacy as a form of complexity. In Conditions (2018), a young man’s face is half hidden by the bloom of a pink peony and a paring knife. In Poster Boys (2019), two sets of Black men’s limbs, a tangle of soft feet and denim, stretch beneath a benevolent portrait of Martin Luther King Jr., tilted just so. It’s an image that pulls together all the exhibition’s strands of atmosphere, narrative, and entanglement, and adds threads of glinting beauty and vulnerability.

Courtesy STARS, Los Angeles

King’s portraits, like Ledare’s installation, create a compelling framework for Love Songs based on knots and entanglements rather than strict binaries. In his text for the new Love Songs catalog, David E. Little, ICP’s executive director since 2021, asks whether pictures of love aren’t a greater, more complex challenge than those showing conflict and struggle. But love isn’t synonymous with intimacy. Each can exist without the other, and intimacy is just as often fraught, messy, and conflicted. Love and war partake of the same tools. Photography is one of them.

Love Songs: Photography and Intimacy is on view at the International Center of Photography, New York, through September 11, 2023.