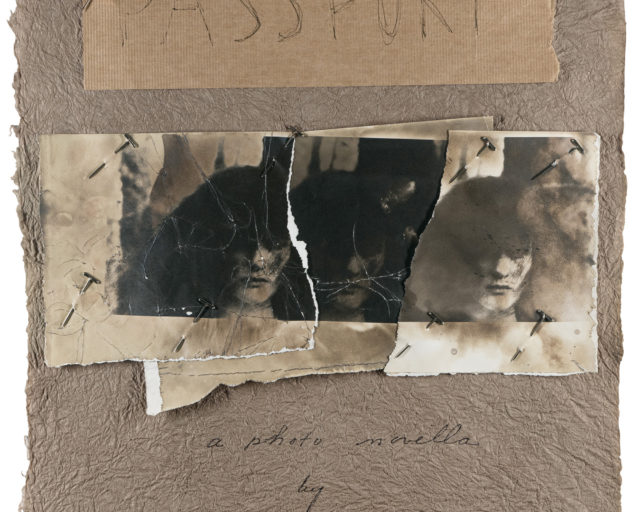

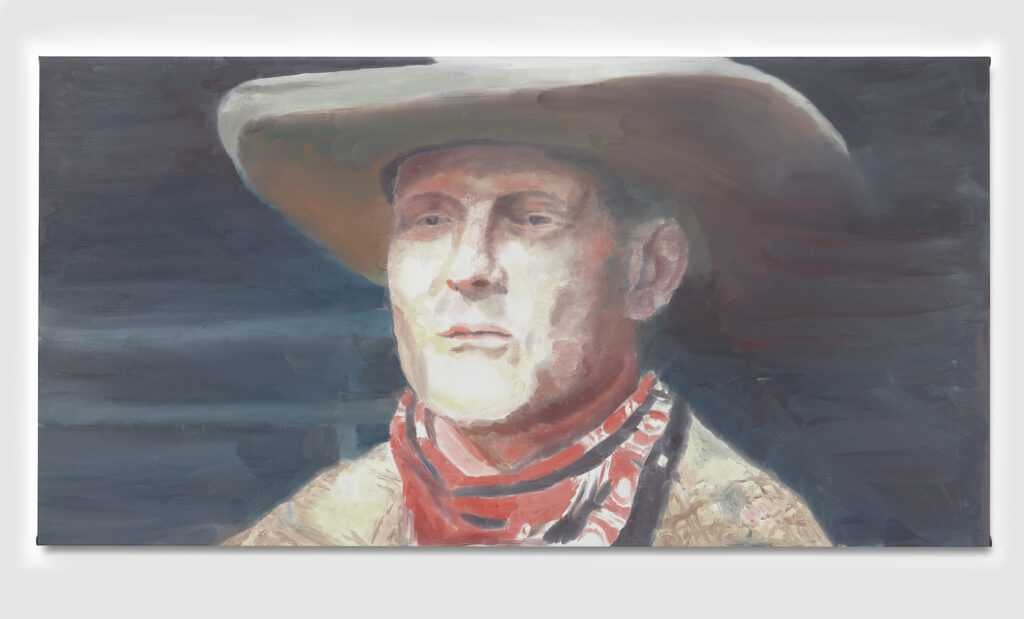

Luc Tuymans, Abe, 2022. Oil on linen

In the late 1970s, when Luc Tuymans started painting, the pursuit was seen as quixotic, archaic. Painting had been declared dead, superseded by Pop and Conceptual art—that is, if we disregard both the bold and wildly colorful brushstrokes of the neo-expressionists and the Transavanguardia, including Julian Schnabel and Francesco Clemente, as well as the cleverly thought through paintings of the older Germans Gerhard Richter, Sigmar Polke, and Anselm Kiefer, who each engaged with the Nazi era in their own ways. In any case, Tuymans, born in 1958 and raised in Belgium, outside of Antwerp, was quite removed from all these conversations.

Tuymans was born into the TV generation, with, as he later put it, “an overdose of images and a lack of meaning.” World War II may have been always present in the media for him, but it remained far from comprehensible. He was three years old when Adolf Eichmann was on trial in Jerusalem—the German SS Obersturmbannführer was being made to answer for the murder of millions of Jews. It was the first such trial to be piped into living rooms across the world. The TV cameras captured a bespectacled man who felt he was not guilty of anything but bureaucratic diligence and obedience. The philosopher Hannah Arendt, covering the trial for the New Yorker, would describe his crimes as “the fearsome, word-and-thought defying banality of evil.” The most terrifying thing about Eichmann, for her, was his normality, so at odds with the atrocities he oversaw; he was somehow both monster and administrator.

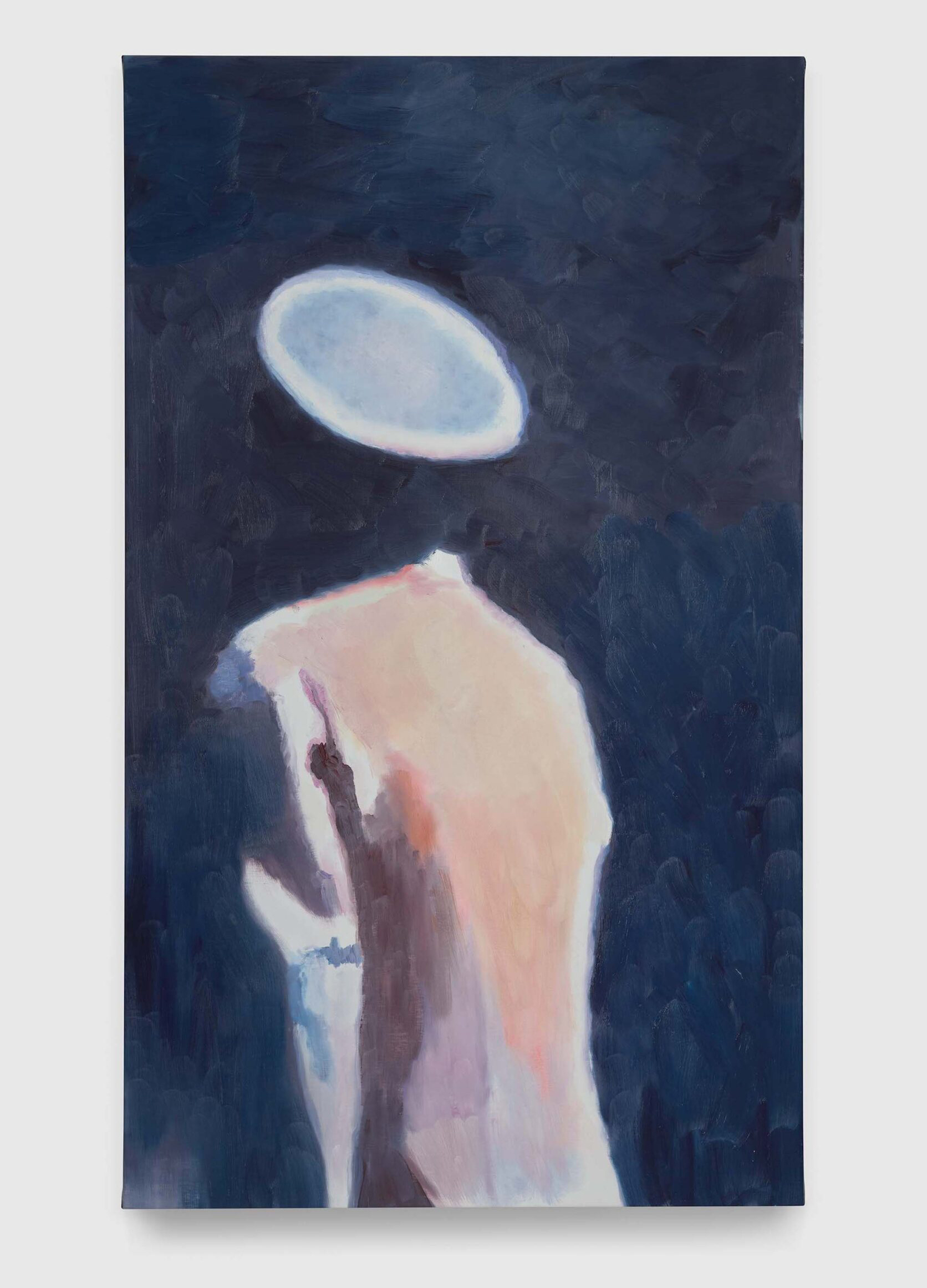

It is precisely this discrepancy, this mismatch between harmlessness and horror, that Tuymans would later address in his paintings. It’s almost as if the trial served as a kind of blueprint for his work, which stands out from that of his peers through its uncanny sense of paralysis. Over the next thirty years, he created paintings whose ghostly, pallid morbidity evokes history and triggers memories—yet transcending mere illustration and eschewing the sensationalism artists’ engagement with the Holocaust can involve. Instead, Tuymans’s paintings speak through their very silence. His only apparently immaterial portraits and interiors convey a particularly dark energy, an ominous atmosphere in which evil is palpable but never exactly present. He models his work after photographs and film stills taken from a wide variety of sources, such as books and postcards, but also photographs or footage taken by himself or others. Tuymans’s art transforms these into something more complex and sinister than historical documents. They gain a ghostly presence that tells of trauma and of death. Death, though always inherent in photography as a medium, here acquires an indefinable, sickly quality that is strangely undead.

Using subjects from the Nazi era early on in his career, the artist set a tone that permeates his oeuvre to this day: seemingly arbitrary, often zoomed-in image sections and laconic titles illustrate topics that elude any poetry. Our New Quarters from 1986 shows a schematically roughed out, anonymous building—giving no indication that it’s actually a courtyard from the “model” concentration camp Theresienstadt, depicted on a postcard that Tuymans saw printed in a book by Alfred Kantor, a Jewish Czech artist who survived three concentration camps. One of these camps was Schwarzheide, of which Kantor made a drawing he then cut into strips to hide it from the SS guards. In 1986, Tuymans used a small section from that composite drawing that depicts a few treetops for a painting titled Schwarzheide; he took up the subject again in 2019. Viewers unfamiliar with its background story remain in the dark.

His painting of a fallen skier whose face remains unrecognizable is similarly unsettling and strange. However innocuous its title—An Architect (1998)—seems, the figure sitting in the snow and turning to us is disturbing. Based on Tuymans’s interest in the Third Reich, we might guess that this is Hitler’s chief architect and armaments minister Albert Speer, whom the artist painted based on historical photographs again and again—along with other Nazi rulers such as Himmler, Heydrich, and Hitler himself. Here, Tuymans used a still from private footage by Speer, in which his face is clearly recognizable despite the poor quality of the film. Tuymans, however, anonymized the architect, rendering identification impossible. Painting him at leisure also creates a stark contrast to his role at Hitler’s side. His snowy fall, on the other hand, points to the downfall of the Nazi regime, of whose brutal “final solution” Speer claimed to have known nothing. Tuymans took a similarly reductive approach to his portrayal of Reinhard Heydrich in his 1988 painting Die Zeit. Heydrich chaired the Wannsee Conference, where the mass murder of European Jews was plotted and decided. The source of this painting came from the propaganda magazine Signal, which dedicated a special issue to Heydrich when he died of sepsis after an assassination attempt by Czech agents. The original photo shows the Nazi sleek and determined in a white fencing jacket with SS badges. Tuymans reduced the image to a few white surfaces, hiding the yellowy face behind sunglasses and posing him as if stuffed in front of a kind of filing cabinet. The typical mixture of anonymization and allegory is at work here too: the man may be unrecognizable, but even detached from his historical context you can sense an abstract threat whose chilling silence sets your imagination reeling.

One might say that Tuymans copied his approach of modeling paintings after photographs and then blurring them from Gerhard Richter. But unlike Richter, who experienced the war himself as a child in Dresden, Tuymans explicitly explores questions of power, representation, and memory—and how they are reflected in images. The Flemish artist certainly also works with blurring and reducing, but whereas Richter used family photos for his paintings on the Nazi era (such as Uncle Rudi [1965], the subject in his Wehrmacht uniform), Tuymans is not concerned with his own personal history, but with the way images, like morgues, can contain rigid and incomprehensible horrors. It is important to note that, at the beginning of the 1980s, Tuymans gave up painting for film for four years. His experience working with a camera, which he used to shoot his own footage but also filmed television broadcasts, often makes his later paintings look like close-ups, or frozen scenes or images, which he also produces in series.

As mysterious and reduced as Tuymans’s paintings appear at first glance, so much in them speaks of the brutality to which their photographic originals silently bore witness.

When asked why he remains captivated by World War II, Tuymans once said that when he was growing up his family constantly talked about this era over dinner. And yet: “Added to this was the tabooing of these events on the grounds that it’s impossible to depict their horror in its entirety.” This is how he came to paint small, excerpted images with a conscious degree of distance and indifference that conveys instead a feeling of what happened, of where it happened. What he thus manages is to interpret visual material artistically and “bring it to the point at which—through the aesthetics of depiction on the one hand and the ethics of what is depicted on the other—it can be interrogated at length. This is the foundation of my painting, which through seeks to give form to feeling, to the inexpressible.”

Tuymans also applies this attitude to topics beyond the Holocaust, such as the Ku Klux Klan, Belgium’s brutal colonial history in the Congo, or 9/11. Images of the last are familiar to us, but he depicted it through a large-scale, classical-looking still life, which offended some people. But it is precisely this distance that demonstrates the power of Tuymans’s method, which is free of nostalgia and irony, making it inexhaustible. His images of images strip the photographic sources of their realistic sharpness and undermine photography’s only recently destabilized claim to truth. Although they remain chilly, because they grant an immediate proximity to—almost an involvement in—historical events, Tuymans creates an atmosphere that takes your breath away.

He succeeds in doing so even when he draws on images of fiction. The Valley (2007) is part of a series based on the 1960s sci-fi horror movie The Village of the Damned, whose parable of mind control is reflected in a boy’s absent gaze and clean-cut aspect. Photographed from the film in extreme close-up, the boy’s face embodies a sense of emptiness and threat in Tuymans’s customary cold blues and grays. But Tuymans also makes use of contemporary pop culture. Based on a photograph the artist took of his television set, the work Big Brother (2008) shows the dormitory of the titular reality show that films its contestants 24 hours a day. Michel Foucault’s analysis of “discipline and punishment”—Tuymans’s central focus, if you will—takes on an absurd dimension here. Instead of in a concentration camp or some boarding school, the people lying in this image are in a TV studio, voluntarily giving away their human dignity to a questionable TV genre. Issei Sagawa (2014), Tuyman’s painting of the Japanese man who murdered and cannibalized a Parisian student in 1981, also stems from a TV documentary. Tuymans took the picture with his smartphone. It shows Sawaga before he committed the crime, wearing a mask and a pith helmet. The transfer of the snapshot into a quickly applied painting reflects the blurring of the video itself, which achieves an eerie effect: the figure appears spooky and frightening, seething with violence and delusion.

Tuymans’s fascination with monstrous characters continues. The cowboy in Still (2019) corresponds to the ominous figure in David Lynch’s Mulholland Drive whose stubbornly white, ice-cold visage shows no feelings. It is hardly surprising that Tuymans has now directed his attention to the pandemic, since silences, standstills, and unconscious biases in our unfolding history conjointly form something like the DNA of his images. Italy (2020) shows a dark, empty piazza above which hovers the digital play button of an online video. Apparently taken directly from a screen, Tuymans’s piece alludes to a present that has come to a standstill, now accessible only via the internet. And when he called his 2022 exhibition at David Zwirner’s Paris location Eternity—the second in a trilogy of exhibitions across Hong Kong, Paris, and New York—he was also referring to a temporality that’s not subject to any chronology. The painting Eternity (2021)—a red shimmering ball that could be the sun or some kind of magic orb—is actually based on the model that the physicist Werner Heisenberg used to design the hydrogen bomb.

All works © the artist and courtesy David Zwirner

Violence, destruction, horror, and death. As mysterious and reduced as Tuymans’s paintings appear at first glance, so much in them speaks of the brutality to which their photographic originals silently bore witness. In Camera Lucida (1980), Roland Barthes describes the paradox that photography can capture for eternity a moment that has passed immediately afterward, which is why photography prematurely mortifies life: “Whether or not the subject is already dead, every photograph is this catastrophe.” Tuymans translates this catastrophic paradox of photography into painting. By engaging in memory work, he keeps us aware that barbarity could break out again at any moment. His paintings somehow exist between times, impossible to be pinned to one particular past. With their strange incorporeality they reach into our world, and these spirits Tuymans keeps evoking will never let us go. Where photography can keep us at a distance, his painting grabs us by the throat. Without any consolation, beyond poetry and nostalgia, they convey the chill of horror, the power of trauma that continues to throb inside of us and is far from defeated.

Translated from the German by Florian Duijsens.