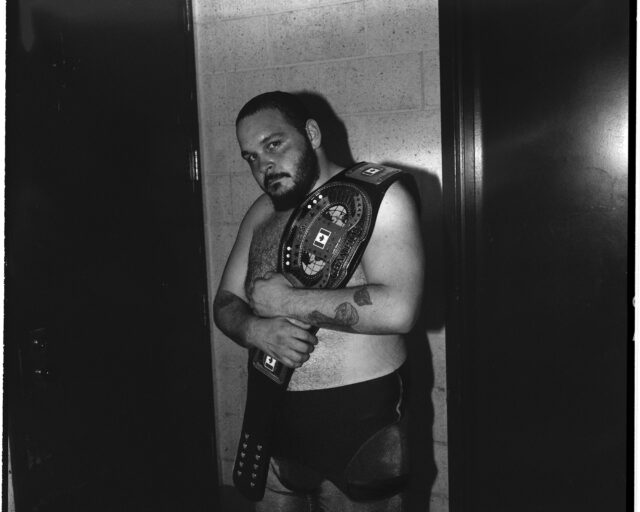

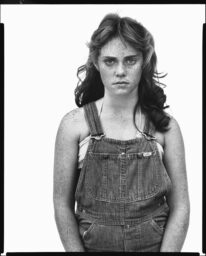

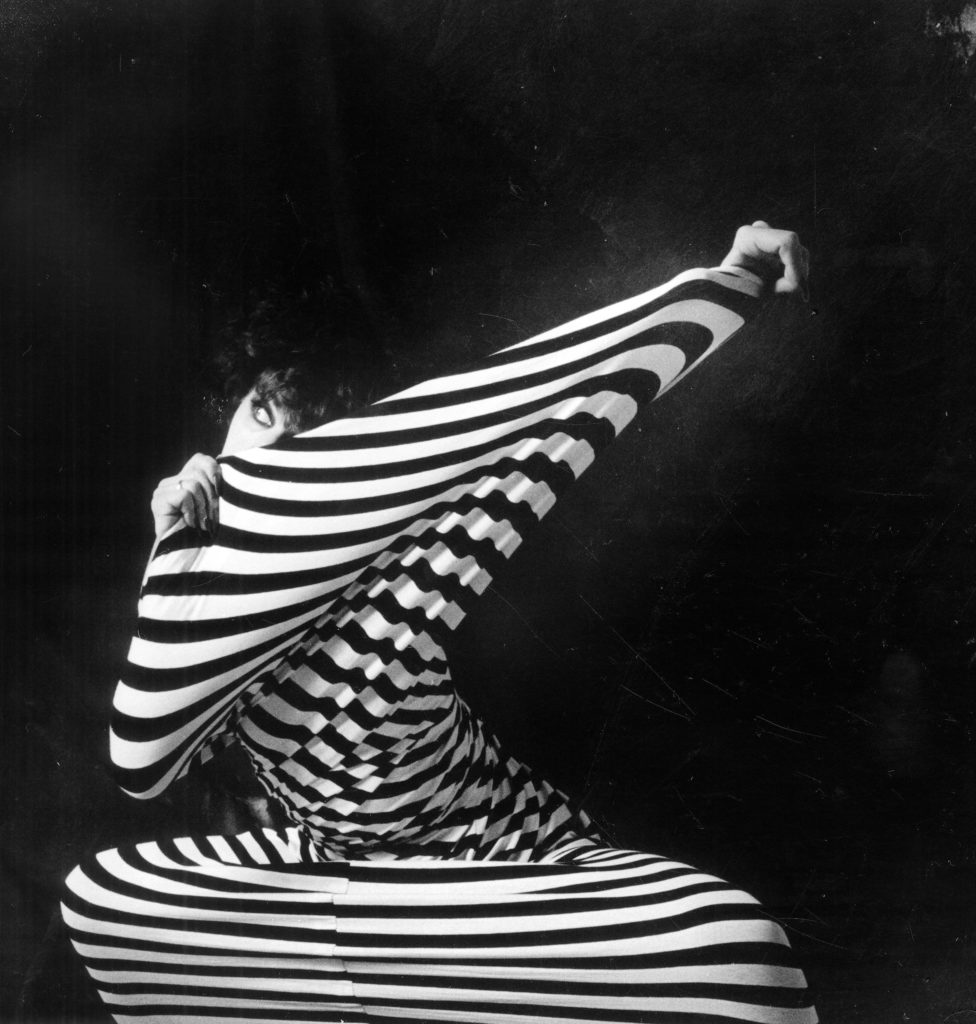

Marcus Leatherdale, Larissa, 1983

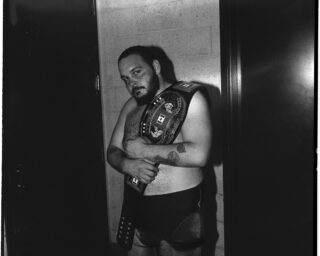

“People thought it was a fake name because I lived in leather. Leather shirts, leather pants, leather jackets,” the photographer Marcus Leatherdale once told me over the phone. Another rumor was that he was the heir to a Canadian logging empire. From the late 1970s until the early 2010s, Leatherdale photographed notable and obscure figures around the world, from New York underground heroes like Cookie Mueller to Bollywood actresses and holy men in India. Looking at photographs of a dashing young Leatherdale, who died last April, one can easily imagine how he elicited a sense of intrigue among admirers, unsettled the stodgy, and inspired rumors among the envious.

Leatherdale was born in 1952 and raised outside of Montreal. He studied fine arts at the École des Beaux-Arts de Montreal, focusing on painting and finding inspiration in formalist beauty and the art of Modigliani, Caravaggio, and Rembrandt. In 1977, he moved to San Francisco to study at the Art Institute. There, he immersed himself in the punk scene and started experimenting with photography. He made his first foray into portraiture outside of the classroom, shooting album covers for his new friends, members of the local cult band The Avengers.

San Francisco is also where Leatherdale met Claudia Summers, who would become his roommate, muse, and eventually, wife. Their marriage began as a practical arrangement between dear friends, as it allowed Leatherdale to remain in the US while traveling freely to visit his family in Canada. But the two also found comfort in each other’s presence, as shape-shifters at ease at mosh pits and gay discos alike. “All these years later, I can still see, feel the flash blinding me, bathing me. The low-dull click of the umbrella flash still resonates in my ears,” Summers writes in Out of the Shadows (2019), an anthology of Leatherdale’s work between 1980 and 1992. “Marcus’s contact sheets were sacrosanct. He shared them with no one but me.”

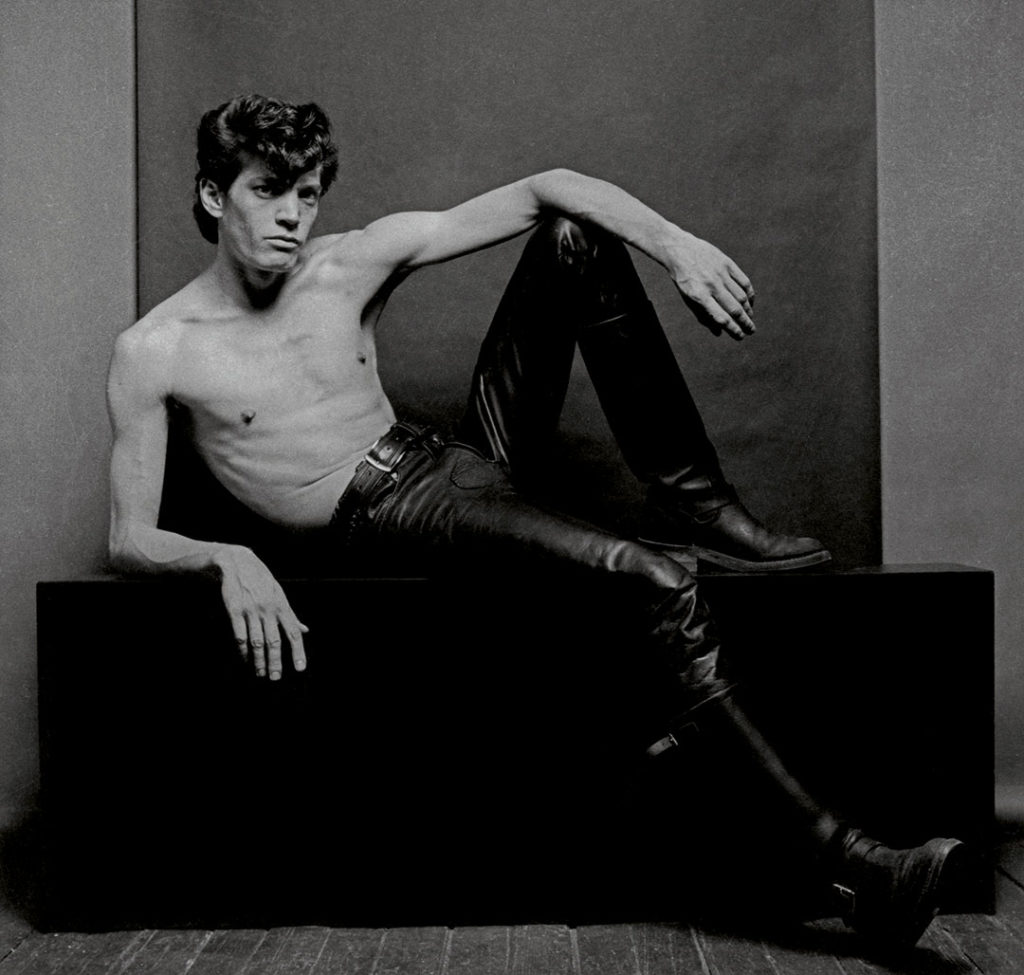

During this time, Leatherdale also met Robert Mapplethorpe, who was visiting from New York for his solo exhibition, Censored, at Simon Lowinsky Gallery. In the spring of 1978, Mapplethorpe sent Leatherdale a postcard, inviting him to stay at his New York apartment while he traveled to Amsterdam. Before the year was over, the young photographer had transferred to the School of Visual Arts in New York, and the two became lovers, starting an intense relationship that lasted for years.

New to the city and having run out of scholarship funds, Leatherdale ended up managing both Mapplethorpe’s studio on Bond Street and, later, the studio of photography curator Sam Wagstaff. It was likely a “cash in hand, work off the books” arrangement, as many things were in those days, says the writer Martin Belk, Leatherdale’s longtime friend.

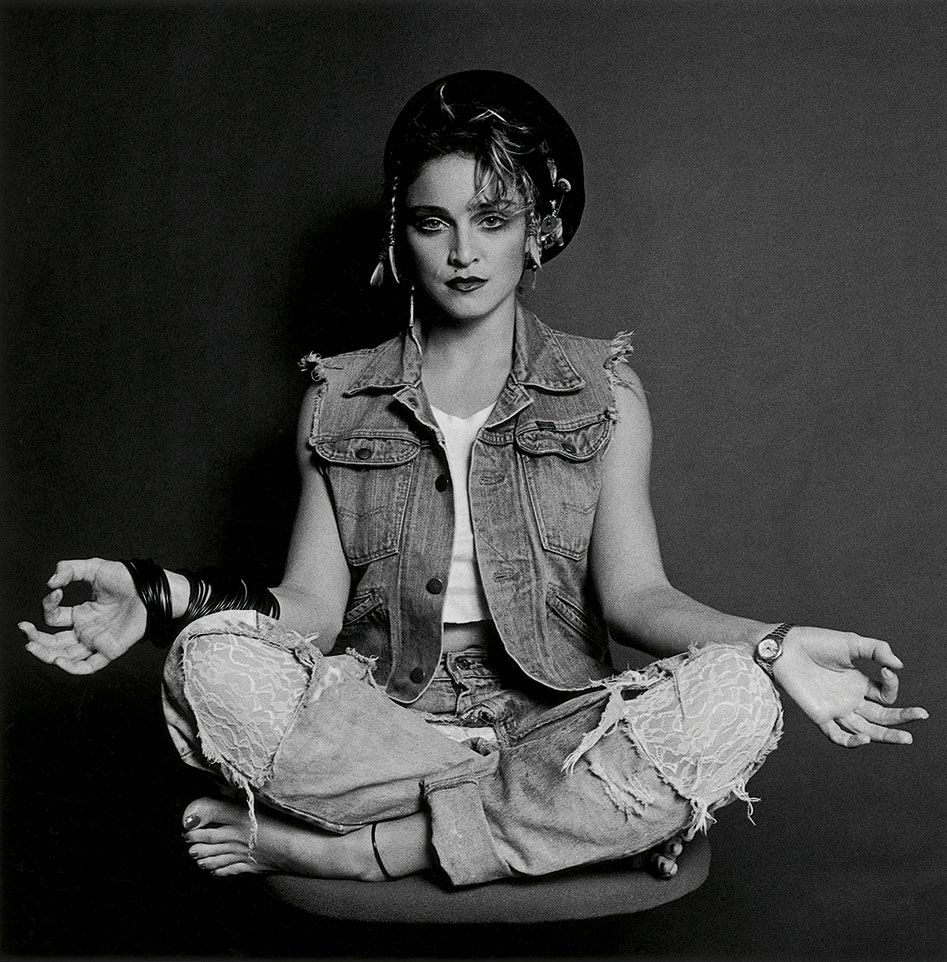

Finding a niche of friends—who also became his subjects—in the downtown nightlife and art scene, Leatherdale evolved as a character-study portraitist, masterfully incorporating myth, melodrama, and identity into his work. He photographed celebrated figures from the art canon, from a young Keith Haring to Andy Warhol and Robert Rauschenberg; fashion luminaries like designer Thierry Mugler and models Tina Chow and Iman; drag queens Divine and Ethyl Eichelberger; nightlife impresarios Susanne Bartsch and Leigh Bowery; and performers Blondie, Lydia Lunch, and International Chrysis.

Key to Leatherdale’s practice was his conviviality. Often, but not always, he photographed at his home studio, a Lower East Side loft on 281 Grand Street. From 1979 to 1985, he lived there with Summers and his cat ZoZo. At the time, Summers worked as a dominatrix and waited tables. She also sang for the 1984 track “The Dominatrix Sleeps Tonight,” which enjoyed popularity in the club scenes of New York, London, and Paris.

“It was not very glamorous. The outside smelled like rotting Chinese food, with lots of trash and dirty boxes,” says the performance artist Joey Arias, another friend of Leatherdale. “But once you were in the sanctuary, it was great.”

Finding a niche of friends—who also became his subjects—in the downtown nightlife and art scene, Leatherdale evolved as a character-study portraitist.

In 1981, Diego Cortez, co-founder of the legendary Mudd Club, included Leatherdale’s portraits in MoMA PS1’s canonical yet controversial New York/New Wave show. Cortez’s curatorial ethos was to provide a platform for downtown’s emergent post-punk and New Wave artists. A portrait of Summers, topless and in a garter belt (a wedding present from Mapplethorpe), was among the works by Leatherdale on view.

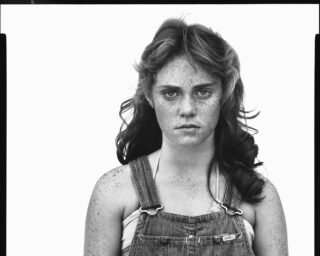

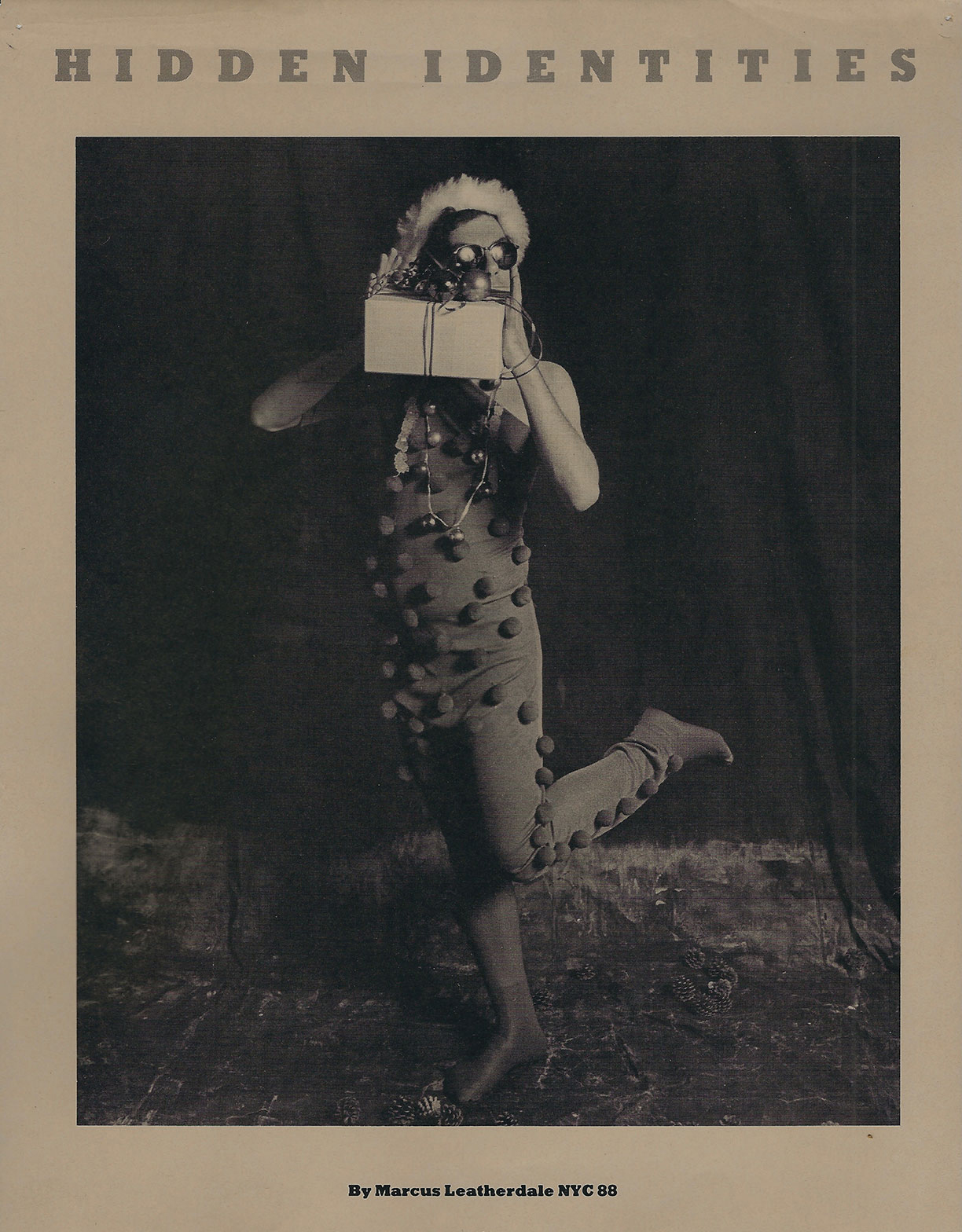

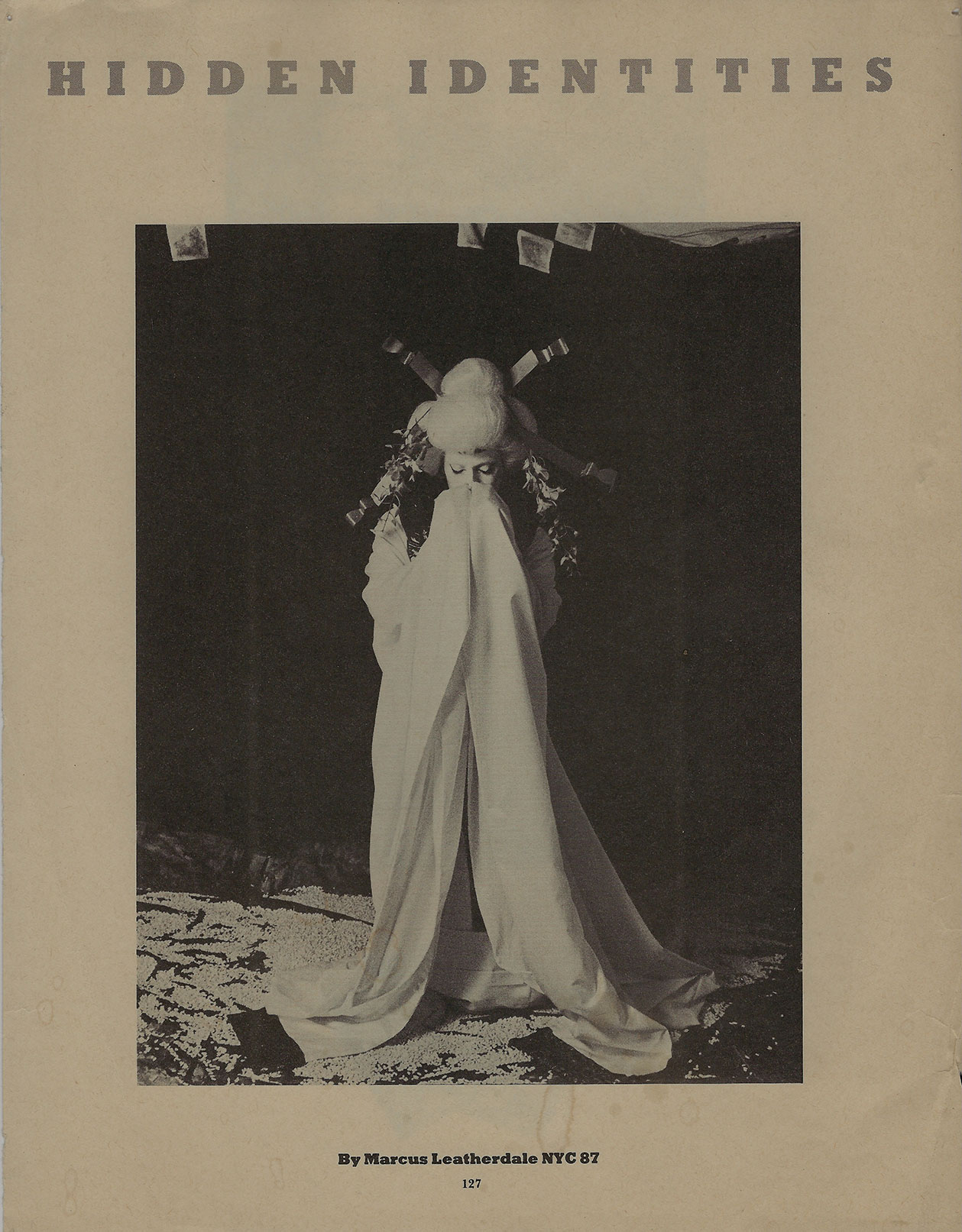

As a result of his hard work and rising reputation, Leatherdale was commissioned the following year to photograph a monthly series in Annie Flanders’s seminal culture magazine, Details. The page-length feature, titled “Hidden Identities,” focused on the who’s who of New York’s downtown scene as artfully as possible, without revealing their faces. “Marcus loved original people that made a statement—visually, mentally,” says Arias.

Leatherdale honed in on his sitters’ inimitable styles; he had no interest in any obvious fashion branding, even though he was photographing some of the era’s most influential designers and models. A young Dianne Brill stands statuesque, the club maven identifiable by her thick, long hair and a signature latex getup. Designer Stephen Sprouse is masked head to toe, save for his punky black nail polish. Then there’s rock and roll designer Betsey Johnson in one of her own creations, stripes and ambitions outstretched.

“It was so Betsey,” Arias recalls, “to be the Martha Graham of fabrics.”

Work continued to go well for Leatherdale. In 1983, as he photographed for Details, he also shot a series of portraits for Issey Miyake’s traveling exhibition and accompanying catalogue, Body Works. Miyake sought out Leatherdale for the “purity of his aesthetic,” says Rande Brown, Body Works’ production coordinator. The commission led to one of Leatherdale’s most famous photographs, often erroneously attributed to Man Ray.

It was of his dear friend Larissa. Known as the Coco Chanel of rock and roll, Larissa designed fur coats for Jimi Hendrix, Miles Davis, and Jefferson Airplane, among others. Using dramatic light and shadow, Leatherdale attunes the viewer to Larissa’s enigmatic grin, the texture of her sheer sleeves, and her half-finished cigarette. Like Summers and Mapplethorpe, Larissa left a lasting impression on Leatherdale. His portrait of her resembles another he made for the same series, of Summers, his most photographed subject, wearing a rattan cage around her torso and a hat, an S and M crop in her hand.

As the first wave of AIDS ravaged New York in the 1980s, Leatherdale experienced a series of life-altering losses. The death of many of his friends and subjects gave his portraits the anthropological patina of a bygone era: downtown New York as a queer Babylon of upstarts, junkies, starlets, and misfits. Leatherdale made a guest list of every friend he had lost, who he would invite to an imaginary cocktail party. Then he began buying new phone books, which allowed him to omit names as opposed to crossing them out, which he felt was disrespectful.

During the 1990s, Leatherdale met and fell in love with Jorge Serio, a makeup artist from Portugal, who became his partner for the rest of his life; still his tether to New York was loosening. He would often leave for months at a time for India, frequently visiting the northern city of Varanasi. Over the course of nearly three decades, Leatherdale learned Hindi and Sanskrit, studied Hinduism, and photographed rural Adivasi tribes whose customs and languages were on the verge of cultural extinction.

To photograph these Adivasi communities, Leatherdale often went on weeks-long expeditions to remote villages, leading to a lifestyle and practice that was considerably off-grid. Privacy—which included creating a refuge for just Jorge and himself—was critical to his self-expression, sense of security, and happiness.

Another series of tragedies shook his life this past year. In July 2021, Serio died. Then the couple’s dear dog Sascha passed, and a few months later, Leatherdale lost his mother, Grace. When Serio died, Leatherdale left Portugal for New York and Canada, and finally returned to India by the winter of 2022, for what would be the last time. In one of our final phone calls, he also expressed another grief that had been more prolonged: the loss of where he came of age as an artist, the rich bohemian world that no longer exists. “Whenever people ask me if I miss New York, I say, ‘Of course, especially when I’m there,’” he would say.

I recently went to 281 Grand with Summers to see what remained. The dirt pits and dope markets on Forsyth, and many of the Jewish linen stores on Grand Street, are gone. And Leatherdale is too. He passed away on April 22, 2022, after hanging himself on the grounds of his estate in Jharkhand, India.

For Summers, the history of 281 Grand, and Leatherdale’s portraits, is something historical as well as deeply personal. It is a place that represents both a generational and an intimate belonging.

“We were all aware of how the work moved against the accepted grain. Not in our community, but outside of it,” she says.

All photographs courtesy Throckmorton Fine Art

Looking back, Summers sees Leatherdale’s gift as this: he could move between the famous and the marginal, photographing both with dignity. “What was so special was that he allowed me the freedom to be who I was—a glamorous but fucked-up individual, sometimes with track marks still on my arms. Marcus photographed the best of who we were.”

I took a photograph of her in front of 281 Grand, and we walked toward what used to be Moishe’s, a diner on Bowery she and Leatherdale frequented for eggs, potatoes, and toast. The rest, she told me, was dangerously bad.