Letizia Battaglia, Rosaria Schifani at her husband’s funeral, 1993

“You seem like such a nice girl,” Letizia kept faxing back to me—always evasive and never, ever answering my usually welcome question: “Are you interested in working with me on a book for Aperture?”

Letizia Battaglia died on April 13, 2022, in Palermo, Italy. She was eighty-seven. I first saw Letizia’s work exposing the Mafia’s oppressive, unrelentingly brutal grip on her native Sicily while working at Aperture Foundation, editing various issues of their quarterly publication, as well as books. At this time, the early to mid-1990s, Letizia was little known in the United States outside photojournalistic circles. In 1985, she had won the coveted W. Eugene Smith Fund Grant for humanistic photography, sharing it with Donna Ferrato—the first time two winners had been named. Then, in May 1986, the New York Times Magazine, in an article titled “Sicily and the Mafia,” published a selection of Letizia’s and Franco Zecchin’s images. Some of the most iconic became forever embedded in the mind’s eye of many—although both photographers were still relatively unknown.

When I decided to devote an issue of Aperture to Italian photography, Immagini Italiane (1993), we included Letizia’s work, accompanied by an interview with the wonderful Italian editor and writer Giovanna Calvenzi, who in 2010 would author Letizia Battaglia: Sulle ferite dei suoi sogni (On the wounds of her dreams). I thought Letizia was pleased, and I was fairly certain she had gone to see and liked the traveling exhibition we did in conjunction with the issue in Venice, where it opened at the Peggy Guggenheim Collection, or in Naples, where it was presented at Museo Diego Aragona Pignatelli Cortes. So why wasn’t she responding “yes” to my book entreaty, or at least acknowledging the question? This was her M.O., I would come to learn, but at the time I was flummoxed—it had become personal.

So, in 1994, I took the long way to Naples, where I had a project, and stopped in Palermo. Letizia saw me for maybe an hour. She showed me not one photograph. We sat in her home, in Palermo’s wonderful old center (I would soon learn that she and others helped to save it from Mafia-plotted destruction), and we shared an espresso together. Still, when I left, I was frustrated and bewildered, not to mention empty-handed. She had promised to send me a package. Yeah, sure: the check was in the mail.

But, wow—I was nonetheless blown away by her. Her fierce intensity felt almost feral. The proverbial force of nature and then some. And not only as a photographer but also as a publisher, Green Party member with the Palermo city council, ecological activist, and defender of women’s and of human rights. We spoke about women, we spoke about justice, she asked me personal questions—not my forte, as I’m so private, but she was like truth serum. I soon understood I was being tested. That she was naturally suspicious. But our conversation was somehow instantly intimate. From that moment on, there was this extraordinary, powerful woman in my life who declared herself my sister, who could get annoyed with me, and who demanded a kind of complicity.

That package bursting with prints, most with handwritten Italian captions scribbled on the backs, arrived two weeks later. Her work took my breath away, as it did for Aperture’s director and publisher at the time, Michael Hoffman. It wasn’t just the photographs’ visual power, or Letizia’s clear commitment to bearing witness to the horrific violence plaguing her city, especially as it affected women and children. It was her all-in engagement, her toughness, her advocacy, her profound sense of justice. Her passion.

And so our story began, as she would only agree to collaborate on the book if I would write the accompanying essay about her that I had asserted was crucial. In this way, I would be invested not just as the book’s editor, but also as the person to whom she would tell her story in words. Of course, I accepted her challenge. Letizia Battaglia: Passion, Justice, Freedom—Photographs of Sicily was published by Aperture in 1999. I have chosen to quote many of her words from the book here, adding context when useful, as Letizia spoke so ardently and persuasively about what mattered to her.

Letizia was born in Palermo on March 5, 1935. Her father was in the navy and they moved around Italy. She spent much of her childhood in Trieste, in the north, and was ten when her family moved back to Palermo. At first she sought freedom by marrying an older man, and with him she had three daughters: Cinzia, Shobha (also a photographer), and Patrizia. But she became desperately unhappy and claustrophobic. She credited the Freudian psychoanalyst Francesco Corrao with helping her to understand that she was strong, telling her, “You can make your own peace, your own equilibrium. You can rebuild your life and save yourself.”

It wasn’t just the photographs’ visual power. It was Battaglia’s all-in engagement, her toughness, her advocacy, her profound sense of justice. Her passion.

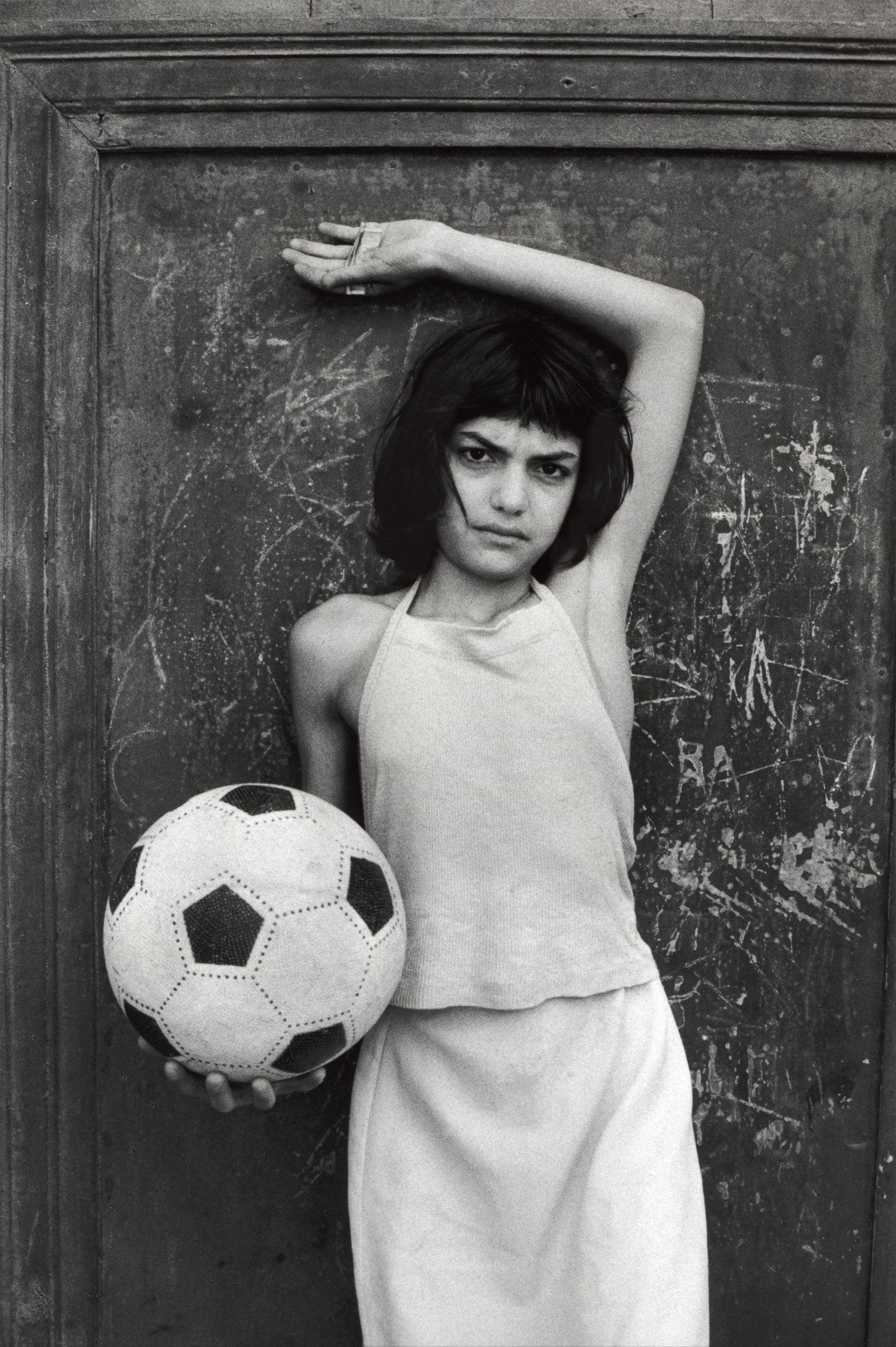

This gave her the strength to leave her husband in 1971, at age thirty-six. She went to Milan and began writing for a newspaper there, while also continuing to write for the left-wing Sicilian daily newspaper L’Ora, as she had done for the previous two years. She had always wanted to be a writer, to tell stories. She soon realized that she’d have more success selling her articles if they were accompanied by images, and so she began making photographs. Very quickly, she just wanted to take pictures. After she had done a small photographic job for L’Ora, the paper asked her to return to Palermo as its director of photography, and she became a full-time photographer. “I think that my life truly began with my camera,” she told me. “I mean my freedom as a person, my voice.” Diane Arbus, Josef Koudelka, Mary Ellen Mark, and Eugene Richards were the photographers whose work she especially admired.

In 1975, she traveled to Venice to see Jerzy Grotowski’s Apocalypsis cum Figuris and met members of his Theatre of Participation. Eventually she ended up working with them, and that’s where she met the twenty-two-year-old Franco Zecchin, who would become her partner in work and life over the next two decades. During our conversations, which took place between 1996 and 1998, she described how their “beautiful story” began:

We spent our first . . . what would you call it . . . encounter on a floor full of dry leaves, because Grotowski was pushing to create things with nature. . . . Bit by bit, we got down in the leaves and began to know each other. After that, I returned to Palermo, and Franco returned to Milan—but then he came to Palermo and stayed for nineteen years. We experienced some very dramatic things together, and accomplished many positive things as well, including our work against the Mafia. Franco was not Sicilian, so it was different for him. He completely understood, but it was more of an intellectual fight for him, whereas for me it was my home, my people, who were so threatened. Besides, I am incapable of elaborating on an intellectual idea with the camera. I live life with the camera. The camera is like a piece of my heart, an extension of my intuition, my sensitivity. . . .

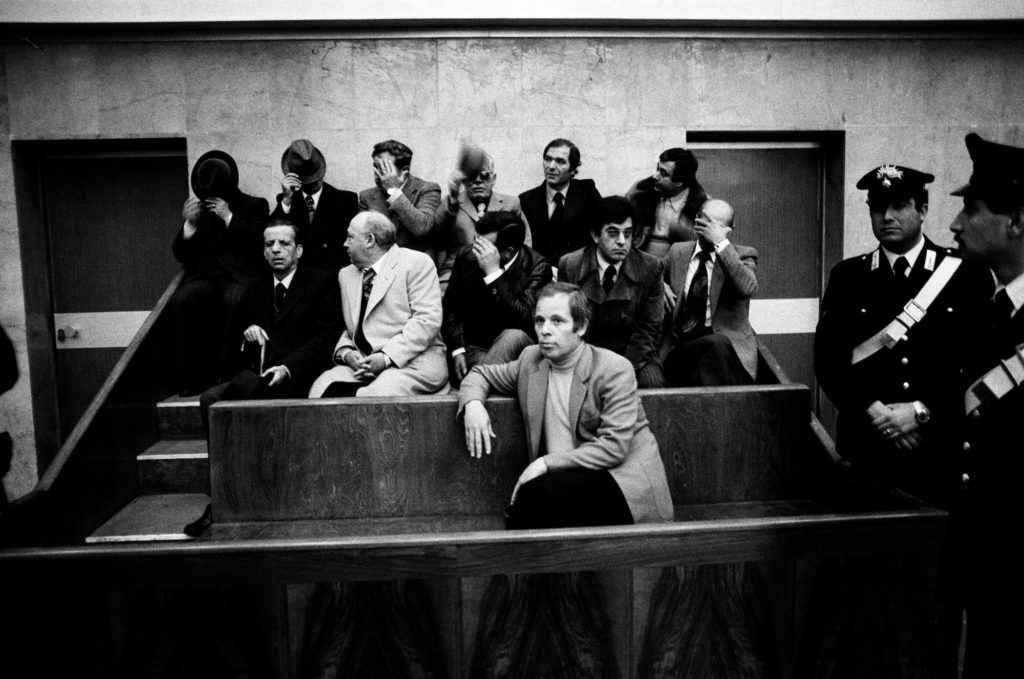

I was bare-handed, except for my camera, against them with all of their weapons. I took pictures of everything. Suddenly I had an archive of blood. An archive of pain, of desperation, of terror, of young people on drugs, of young widows, of trials and arrests. There in my house, Franco Zecchin and I were surrounded by the dead, the murdered. It was like being in the middle of a revolution. I was so afraid.

One of Letizia’s and Zecchin’s most provocative and risky actions was displaying large-scale prints of their images of Mafia victims in Corleone’s main piazza. Letizia was desperate for her fellow Sicilians to truly understand the Mafia’s barbarity, and to speak up and out against them, despite her understandable fear. The acute brilliance of her reportage was always intertwined heart and soul with her activism.

Letizia’s own performative nature and instinct to take it to the streets eventually led her to enter politics. She met Mayor Leoluca Orlando when she was first elected to Palermo’s Municipal Council in 1985; although they were not predisposed toward working together, they soon completely accepted, trusted, and respected each other—especially once Letizia understood that he was “ferociously anti-Mafia, and also much more progressive than I was at the time on issues of the environment, for example.” They ultimately became close collaborators and friends, and Orlando poetically expressed his appreciation for Letizia’s heart, mind, and willfulness in a letter to her, written for our book.

About her work in politics, Letizia told me:

When I stopped taking pictures and entered politics—first as municipal councilwoman, then as regional deputy, and lastly as municipal councilwoman again—I was afraid I had betrayed photography, and maybe even the struggle, since I had felt that taking pictures was my only weapon. But then I realized that the same motivation lies behind my photography and my politics, the same will to combat, to stay on the front line. Working in a different way, I could accomplish different things. So, despite many difficult times, we continued into the eighties with our politics, photography, publishing, meetings, and anti-Mafia demonstrations. And then came those wonderful men who gave us such hope—Judge Giovanni Falcone, Judge Paolo Borsellino—prosecutors who were good and brave; and who then, in 1992, were murdered.

Another contributor to the book Passion, Justice, Freedom was Magistrate Roberto Scarpinato, who at the time was prosecuting Italy’s ex–prime minister Giulio Andreotti for collusion with the Mafia—and using one of Letizia’s photographs as evidence. Also writing for our book and discussing this image, along with her work in general, was journalist Alexander Stille, author of Excellent Cadavers (1995), which insightfully chronicles the violence and workings of the Sicilian Mafia in light of the assassinations of Falcone and Borsellino. In 2005, when Marco Turco turned Excellent Cadavers into a film, Letizia’s commanding presence throughout was electrifying.

Letizia’s approach was one of advocacy and empowerment, especially of women, on the most human and humane level. In Palermo she started a women’s theater project, and when she began her publishing house the initial idea was to give women (although not exclusively women) a place to be heard, a platform. The principal motivation for these books was desperation after the murders of Falcone and Borsellino, but Edizioni della battaglia soon embraced talented voices and addressed the struggle for human rights worldwide. In time, Mayor Orlando assigned her a counseling position to work with prisoners in Palermo: “It’s necessary,” she told me, “to work for justice but also to help those who have made mistakes to transform their lives.” She and Zecchin also set up a photography school and volunteered in the psychiatric hospital in Palermo, working with the patients. Around 2013, Letizia told me about the photography center she had conceived for Palermo: Il Centro Internazionale di Fotografia—Cantieri culturali alla Zisa. She asked if I’d curate one of the first exhibitions; she wanted a show of American women photographers. And, would I please include Mary Ellen Mark? Mary Ellen, who died in 2015, consented without hesitation. “For Letizia.”

All photographs © Letizia Battaglia

In the summer of 2015, I received an email from Letizia further describing the center. Mayor Orlando had provided funding to restore the building, “but there will be no money for anything else. . . . I need the help of many,” she wrote. “I need photographers who will give me photographs to exhibit at no cost. Everyone must know that I have much respect for the photographs and photographers. This is a heroic operation, because it was born in Palermo, still the powerful city of the Mafia. Whoever helps me has to do it by faith.”

I sent a rough translation to Nina Berman, Lynsey Addario, Donna Ferrato, Graciela Iturbide, Mary Ellen Mark’s studio, Susan Meiselas, Sylvia Plachy, and Stephanie Sinclair. These remarkable photographers joined forces with me (as did designer Yolanda Cuomo and translator Meg Shore). The 2018 show, Donne Fotografano Donne (Women Photograph Women), was born. Letizia was profoundly moved by their generosity of spirit and the support of her community. She understood that this exhibition came about because of the woman and photographer we all understood her to be. This spring, Mayor Orlando announced that the Palermo photography center would be renamed in her honor.